Harry de Cleyre

Harry de Cleyre | |

|---|---|

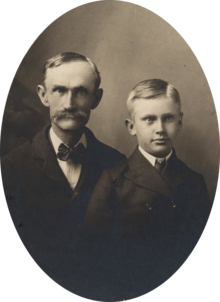

A young De Cleyre (right) with his father (left) | |

| Born | Vermorel Elliott June 12, 1890 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died | April 1974 (aged 83) Bucks County, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Resting place | Ringoes, New Jersey |

| Occupation | House painter |

| Spouse |

Hertha R. Behr (m. 1917–1974) |

| Children | Voltairine, Fedora and Renée |

| Parents |

|

Harry de Cleyre (1890–1974) was an American house painter and writer. The son of Voltairine de Cleyre and James B. Elliott, he was abandoned by his mother and neglected by his father during his childhood. He struggled to apply himself in his education and was forced to start work at the age of 10. After his mother's death, he devoted himself to studying her work and preserving her memory; he became a key primary source on her life, writing several letters about her to Joseph Ishill and Agnes Inglis.

Biography

[edit]Harry de Cleyre was born on June 12, 1890, in Philadelphia, the son of the anarchist Voltairine de Cleyre and the freethinker James B. Elliott.[1] He was born by the name Vermorel Elliott, named after the Communard Auguste-Jean-Marie Vermorel.[2] His mother was neither physically nor emotionally able to cope with raising Harry, so she left him in the care of his father.[3] Feeling abandoned, Harry would refer to himself as a "bastard" throughout the rest of his life.[4]

De Cleyre's mother remained a stranger to him during his early life, even though she lived close by. According to Harry's own daughters, "he just did not fit into her life, her plans, at all."[5] She briefly attempted to give him piano lessons,[6] but he didn't apply himself, so she stopped.[7] By the turn of the century, his father had succombed to mental illness and left him to fend for himself.[8] He went to work at the age of 10, his income supplemented only by a small weekly allowance from his mother. His aunt Adelaide D. Thayer remembered him always feeling depressed, which she attributed to his mother.[7] At one point, Thayer asked if she could take care of him; while his mother cared little for what was done with him,[9] his father refused to relinquish custody.[7] At the age of 16, he enrolled in a technical school, as he had grown up loving machines and wanted to learn mechanical engineering. Although he was financially supported by his mother, he failed to apply himself to his studies, so his mother refused to pay for any more of his education.[4] He later went to work as a housepainter.[10]

He became closer with his mother once he reached the age of 15.[8] By 1906, he was living with his mother and for some time paid her rent.[11] She later recalled his passion for repairs and machinery,[12] and assured her sister that rumors he had become a priest were untrue, saying: "he is an ignorant boy and an alcoholic wreck; they wouldn't take him in for a minute."[13] According to Emma Goldman, while he was "overawed" by his mother's intellect, he was also "repelled by her austere mode of living."[14]

In the spring of 1912, when his mother was on her deathbed, he travelled to Chicago to be by her side when she died.[15] After his mother's death, Emma Goldman speculated that Harry had gone his own way,[16] becoming "one of the 100% Americans, commonplace and dull."[10] Although neglected by his mother throughout his life, he never stopped loving her, even naming his eldest daughter "Voltairine". He also dropped his father's surname and adopted his mother's.[17] While the rest of his maternal family continued to spell their name "De Claire", Harry adopted his mother's fashion of spelling it as "de Cleyre".[18] Although he never took up his mother's anarchist philosophy, he expressed pride in her "stubborn defense of those being oppressed."[16] He also inherited his parents' love of Thomas Paine,[19] which he passed on to his own daughters, and treated his mother's Selected Works as his own personal Bible.[10]

Later in his life, he spent much of his time talking about his mother.[16] In a letter he sent to Joseph Ishill on October 15, 1934, he pointed out a number of mistakes in Emma Goldman's biography of De Cleyre, including the date and circumstances of her death, the false assertion that her father Hector De Claire had wanted her to become a nun, and the details of her lingustics tutoring. Nevertheless, he still described Goldman's biography as a "glowing tribute".[20] In the same letter, he also described his mother's student Nathan Navro as "a man whose integrity is unquestioned", praising him for being "free of petty jealousies", unlike some of his mother's other admirers.[21] In an October 28, 1934 letter to Joseph Ishill, de Cleyre described his mother's time in a convent, where according to him, she was allowed access to the Bible, which "was denied to those of the Catholic faith."[22] In an October 12, 1947 letter to Agnes Inglis, de Cleyre described his grandfather as a "petty tyrant".[23] He also mentioned about how, during her time in a convent, his mother had considered becoming a nun.[24] On December 29, 1947,[25] he told Inglis that his mother had confided to him that it was Dyer Lum who had smuggled an explosive to Louis Lingg, which had allowed him to commit suicide.[26] Inglis herself didn't believe this, thinking the prison authorities had killed Lingg, but this hypothesis was disputed by Alexander Berkman.[27] On February 15, 1948, he confessed to Inglis of how his mother had been acquitted in a trial for incitement to riot, after her co-defendant Chaim Weinberg had bribed a witness to not testify.[28]

Harry de Cleyre died in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in April 1974.

References

[edit]- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 71; Marsh 1981, p. 130; Sartwell 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 71n5.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 71–72; DeLamotte 2004, pp. 84–85; Marsh 1981, p. 130; Sartwell 2005, p. 6.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 73.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 72.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 72–73; DeLamotte 2004, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Avrich 1978, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Marsh 1981, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 72–73; DeLamotte 2004, pp. 84–85; Marsh 1981, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b c Avrich 1978, pp. 73–74.

- ^ DeLamotte 2004, pp. 85, 159.

- ^ DeLamotte 2004, pp. 85, 176–177.

- ^ DeLamotte 2004, pp. 85, 188.

- ^ Presley 2005, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 73–74, 235–236; DeLamotte 2004, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b c Avrich 1978, pp. 73–74; Presley 2005, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 73–74; DeLamotte 2004, p. 85; Presley 2005, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 40n4.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 73–74; Presley 2005, p. 28.

- ^ Presley 2005, p. 27.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 31.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 22.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 34.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 63–64; DeLamotte 2004, p. 85.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 64.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 201-202n22.

Bibliography

[edit]- Avrich, Paul (1978). An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04657-0.

- DeLamotte, Eugenia (2004). Gates of Freedom: Voltairine de Cleyre and the Revolution of the Mind. University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.11482. ISBN 0-472-09867-5. JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.11482. LCCN 2004006183.

- Golder, Lauren J. (2023). "A Politics of Suffering: Anarchism and Embodiment in the Life of Voltairine de Cleyre". Gender & History. doi:10.1111/1468-0424.12678. ISSN 1468-0424.

- Marsh, Margaret S. (1981). "No Illusions: The Anarchist Life of Voltairine de Cleyre". Anarchist Women, 1870–1920. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 123–150. ISBN 978-0-87722-202-6.

- Presley, Sharon (2005). "Emma Goldman's 'Voltairine de Cleyre': A Moving but Flawed Tribute". In Sharon, Presley; Sartwell, Crispin (eds.). Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine De Cleyre – Anarchist, Feminist, Genius. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-7914-6094-8.

- Sartwell, Crispin (2005). "Priestess of Pity and Vengeance". In Sharon, Presley; Sartwell, Crispin (eds.). Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine De Cleyre – Anarchist, Feminist, Genius. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-0-7914-6094-8.