Henry K. Van Rensselaer

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: The article needs a good copy-edit. (December 2012) |

Henry K. van Rensselaer, his given name Hendrick Kiliaen (July 25, 1744 – September 9, 1816)[1] was a Colonel during the American Revolutionary War when he played a pivotal role in the Battle of Fort Anne.

Early life

[edit]Henry Kiliaen Van Rensselaer was born on July 25, 1744. He was the eldest son of nine children born to Col. Kiliaen Van Rensselaer (1717–1781) of the 4th Albany Regiment of Militia, by the former Ariaantie Schuyler (1720–1763).[1] Among his siblings were brothers Philip K. Van Rensselaer and Killian K. Van Rensselaer.[2]

His paternal grandfather was Hendrick van Rensselaer, who built Fort Crailo.[1]

Military experience

[edit]

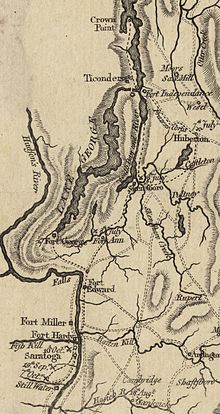

Henry van Rensselaer engaged in a fierce battle near Fort Anne, acting on orders from General Philip Schuyler. He was given at least two objectives: hold the enemy at Fort Anne in order to facilitate the removal of cannon and armaments at Fort Amsterdam, to a place of safety; and assist Colonel Pierse Long with his retreat from the 1777 Battle of Ticonderoga. He commanded a regiment of 500 men mustered from men in the Van Rensselaer Manor.[3]

Colonel John Hill and his British troops pursued the Rebels of the Crown from Lake Champlain up Wood creek to a point North East of Fort Anne. As planned, Van Rensselaer met Long and his regiment from New Hampshire to assist in their retreat. Their objective was to slow British movement. They assessed a numerical advantage over the British. Meanwhile, what appeared to be an American traitor, tricked Colonel Hill into believing there were twice as many as the true amount of Rebel troops. This news may have made Hill act more cautiously than he had planned, knowing his reinforcements have not arrived and otherwise not wanting to be spotted in an unprovoked retreat.

A series of retreats and advances by the Patriots and the British culminated into a two sided bombardment. Van Rensselaer led an advance on British troops when he was shot in the thigh through to his knee, shattering his femur. As he lie near the British troops, he could hear little noise. He was confident the British were in retreat as he ordered his troops to "Attack! ...Attack"! Colonel van Rensselaer is credited for this critical decision in the battle of Fort Anne, July 8, 1777.[4]

Not only were the British delayed, but forced into retreat after Van Rensselaer launched a decisive assault, spanning 2 hours of all-out battle. Nearly all munitions from both Patriots and British alike were exhausted on their opposing forces. The British were so overwhelmed, when the battle ended, they were left little choice - but to retreat and abandon several of their wounded on the field to be taken prisoner. Neither the Patriots nor the British knew their opponent's supplies were crucially low.

The Patriots proceeded to Fort Anne with their prisoners, two injured and two men who gave the ultimate sacrifice for liberty; Sgt. Isaac Davis and Ens. Christopher Walcutt.

Their stay at Fort Anne was short. They were looking forward to a 14-mile - seven-hour journey, munitions were nearly depleted, rain was on its way and food was in short supply. As they left they were determined in preventing the British from making use Fort Anne, it was set ablaze and Van Rensselaer's regiment placed every conceivable obstacle behind in their path by felling trees and rolling boulders into the road to hinder any British advance as the Rebels made their way to Fort Edward.

Personal life

[edit]He married Alida Bradt (1742–1795), a daughter of Hendrick Bradt and Rebecca (née Van Vechten) Bradt.[5] Together, they had:[6]

- Catharine Van Rensselaer (1773–1846), who married Cornelius Schermerhorn (1769–1860) in 1793.[7][8]

- Solomon Van Vechten Van Rensselaer (1774–1852),[3] who married his first cousin, Harriet Van Rensselaer (1775–1840), daughter of Philip Kiliaen van Rensselaer[9]

- John Henry Van Rensselaer (1778–1838), who married Maria Lansing (1780–1848).[6][10]

After his first wife's death in 1795, he remarried to Nancy Gertrude Semons (1775–1876). Together, they were the parents of:[6]

Van Rensselaer died on September 9, 1816. His second wife lived a widowed life for more than sixty years until her death on December 30, 1876.[11]

Legacy

[edit]Among his descendants is his granddaughter Catharina Visscher Van Rensselaer Bonney, author of A Legacy of Historic Gleanings.[2]

A number of van Rensselaer houses survive and are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The home of Hendrick van Rensselaer (Hendrick I. van Rensselaer?), a relative, was built in 1785 and, as the Hendrick Van Rensselaer House, was featured in 2022 as one of the oldest homes in the Hudson Valley.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c A Legacy of Historical Gleanings. J. Munsell. 1875. pp. 10, 91. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ a b Bonney Van Rensselaer, Catharina Visscher (1875). A Legacy of Historic Gleanings. Albany N.Y.: J. Munsell.

- ^ a b "Death of General Van Rensselaer" (PDF). The New York Times. April 26, 1852. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Bird, Harrison (1963). March To Saratoga General Burgoyne And The American Campaign 1777. Oxford University Press. pp. 51–57. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Munsell, Joel (1871). Collections on the History of Albany: From Its Discovery to the Present Time; with Notices of Its Public Institutions, and Biographical Sketches of Citizens Deceased. Albany, NY: J. Munsell. p. 184e.

- ^ a b c d e Rensselaer, Florence Van (1956). The Van Rensselaers in Holland and in America. New York. pp. 49–50. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Revolution, Daughters of the American (1899). Lineage Book. The Society. p. 73. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Dwight, Benjamin Woodbridge (1874). The History of the Descendants of John Dwight, of Dedham, Mass. J. F. Trow & son, printers and bookbinders. p. 877. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Bielinski, Stefan. "Solomon Van Rensselaer". exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov. New York State Museum. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ^ "The American Historical Magazine". Publishing Society of New York. 1907: 192. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Congress, United States (1860). The Congressional Globe. Blair & Rives. p. 1334. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "One of the Oldest Homes in New York's Idyllic Hudson Valley ..." July 18, 2022.