Historiography of World War II

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

The Historiography of World War II is the study of how historians portray the causes, conduct, and outcomes of World War II. There are many different perspectives, however the three main are the Orthodox from the 1950s, Revisionist from the 1970s and Post-Revisionism which offers the most contemporary perspective.

The Orthodox perspective arose during the aftermath of the war. The main historian noted for this perspective is Hugh Trevor-Roper. Orthodox Historians argue that Hitler was a master planner who intentionally started World War II due to his strong beliefs on Fascism, expansionism, and the supremacy of the German State.[1] The Revisionist perspective became popular during the 70s. This viewpoint is very liberal and the main historians from this period are Howard Zinn and A. J. P. Taylor. Revisionist Historians argue that Hitler was an opportunist and took advantage of the opportunities given to him. Throughout the course of the war, Orthodox Historians argue as if the Axis powers were a sort of evil consuming the world with their powerful message and malignant ideology, while the Allied powers were trying to protect democracy and freedom.

While Revisionist Historians argue that the Allied powers of World War II continued their involvement in the war due to the clear economic, political and military advantages.[2] Post Revisionist historians, such as Alan Bullock argue that the cause of the War was a matter of both factors. Essentially Hitler was a strategist with clear aims and objectives, that would not have been achievable without taking advantage of the opportunities given to him.[3] Each perspective of World War II offers an insightful analysis and allows us to expand our curiosity on the blame, conduct and causes of the war.

Historiographical Viewpoints

Self esteem and glory

R.J. Bosworth argues the major powers have experienced intellectual conflict in interpreting their wartime stories. Some have ignored the central issues. Germany and, to a much lesser extent, Japan have experienced a collective self-analysis. But these two, as well as Great Britain, France, Russia, and Italy, have largely ignored many roles and have looked instead for glory evcen when it was lacking.[4]

Blame

Blame as the driving force during World War II, is a widely known Orthodox persepective. Especially directly after World War II, Nazi Germany was held to blame for starting the war. Orthodox Historians cited several reasons for this. Germany was the one who initially invaded Poland against the recommendation of the allies, and also attacked the Soviet Union.[5] Also, the system of alliances between the Axis Powers was one that was only meant for war. The tripartite pact stated that if any country declared war on one of the Axis countries, the other two would also declare war on those countries. Another reason, historians saw, is that the policies of Hitler were overly aggressive; not only did Hitler preach war with France and the Soviet Union, but he followed a careful pre-made plan of expansionism. Additionally, the events that took place in unveiling of the war such as the Remilitarization of the Rhineland, Anschluss, and the German involvement during the Spanish Civil War, showed that Hitler was anticipating the possibility of war and intentionally gearing up for it.[6]

Canada

Canada deployed trained historians to Canadian Military Headquarters in the United Kingdom during the war, and paid much attention to the chronicling of the conflict, not only in the words of the official historians of the Army Historical Section, but also through art and trained painters. The official history of the Canadian Army was undertaken after the war, with an interim draft published in 1948 and three volumes in the 1950s. This was in comparison to the First World War's official history, only 1 volume of which was completed by 1939, and the full text only released after a change in authors some 40 years after the fact. Official histories of the RCAF and RCN in the Second World War were also a long time coming, and the book Arms, Men and Government by Charles Stacey (one of the main contributors to the Army history) was published in the 1980s as an "official" history of the war policies of the Canadian government. The performance of Canadian forces in some battles have remained controversial, such as Hong Kong and Dieppe, and a variety of books have been written on them from various points of view. Serious historians - mainly scholars - emerged in the years after the Second World War, foremost Terry Copp (a scholar) and Denis Whitaker (a former soldier).[7]

Taylor The Origins of the Second World War (1961)

In 1961, English historian A. J. P. Taylor published his most controversial book, The Origins of the Second World War, which earned him a reputation as a revisionist—that is, a historian who sharply changes which party was "guilty." The book had a quick, profound impact, upsetting many readers.[8] Taylor argued against the standard thesis that the outbreak of the Second World War – by which Taylor specifically meant the war that broke out in September 1939 – was the result of an intentional plan on the part of guilty Adolf Hitler. He began his book with the statement that too many people have accepted uncritically what he called the "Nuremberg Thesis", that the Second World War was the result of criminal conspiracy by a small gang comprising Hitler and his associates. He regarded the "Nuremberg Thesis" as too convenient for too many people and claimed that it shielded the blame for the war from the leaders of other states, let the German people avoid any responsibility for the war and created a situation where West Germany was a respectable Cold War ally against the Soviets.

Taylor's thesis was that Hitler was not the demoniacal figure of popular imagination but in foreign affairs a normal German leader. Citing Fritz Fischer, he argued that the foreign policy of the Third Reich was the same as those of the Weimar Republic and the Second Reich. Moreover, in a partial break with his view of German history advocated in The Course of German History, he argued that Hitler was not just a normal German leader but also a normal Western leader. As a normal Western leader, Hitler was no better or worse than Stresemann, Chamberlain or Daladier. His argument was that Hitler wished to make Germany the strongest power in Europe but he did not want or plan war. The outbreak of war in 1939 was an unfortunate accident caused by mistakes on everyone's part.

Notably, Taylor portrayed Hitler as a grasping opportunist with no beliefs other than the pursuit of power and anti-Semitism. He argued that Hitler did not possess any sort of programme and his foreign policy was one of drift and seizing chances as they offered themselves. He did not even consider Hitler's anti-Semitism unique: he argued that millions of Germans were just as ferociously anti-Semitic as Hitler and there was no reason to single out Hitler for sharing the beliefs of millions of others.

Taylor argued that the basic problem with an interwar Europe was a flawed Treaty of Versailles that was sufficiently onerous to ensure that the overwhelming majority of Germans would always hate it, but insufficiently onerous in that it failed to destroy Germany's potential to be a Great Power once more. In this way, Taylor argued that the Versailles Treaty was destabilising, for sooner or later the innate power of Germany that the Allies had declined to destroy in 1918–1919 would inevitably reassert itself against the Versailles Treaty and the international system established by Versailles that the Germans regarded as unjust and thus had no interest in preserving. Though Taylor argued that the Second World War was not inevitable and that the Versailles Treaty was nowhere near as harsh as contemporaries like John Maynard Keynes believed, what he regarded as a flawed peace settlement made the war more likely than not.[9]

Battle of France, 1940

The German victory over French and British forces in the Battle of France was one of the most unexpected and astonishing events of the 20th century, and has generated a large popular and scholarly literature.[10]

Observers in 1940 found the events unexpected and earth shaking. Historian Martin Alexander notes that Belgium and the Netherlands fell to the German army in a matter of days and the British were soon driven back to their home islands:

- But it was France's downfall that stunned the watching world. The shock was all the greater because the trauma was not limited to a catastrophic and deeply embarrassing defeat of her military forces - it also involved the unleashing of a conservative political revolution that, on 10 July 1940, interred the Third Republic and replaced it with the authoritarian, collaborationist Etat Français of Vichy. All this was so deeply disorienting because France had been regarded as a great power....The collapse of France, however, was a different case (a 'strange defeat' as it was dubbed in the haunting phrase of the Sorbonne's great medieval historian and Resistance martyr, Marc Bloch).[11]

One of the most influential books on the war was written in summer 1940 by French historian Marc Bloch: L'Étrange Défaite ("Strange Defeat"). He raised most of the issues historians have debated since. He blamed France's leadership:

- What drove our armies to disaster was the cumulative effect of a great number of different mistakes. One glaring characteristic is, however, common to all of them. Our leaders...were incapable of thinking in terms of a new war.[12]

Guilt was widespread. Carole Fink argues that Bloch:

- blamed the ruling class, the military and the politicians, the press and the teachers, for a flawed national policy and a weak defense against the Nazi menace, for betraying the real France and abandoning its children. Germany had won because its leaders had better understood the methods and psychology of modern combat.[13]

Eastern Front

It is commonly said that history is written by the victors; but the exact opposite occurred in the chronicling of the Eastern Front, particularly in the West. Soviet secrecy and unwillingness to acknowledge events that might discredit the regime led to them revealing little information, always heavily edited - leaving western historians to rely almost totally on German sources. While still valuable sources, they tended to be self-serving; German generals in particular tried to distance themselves and the Heer as a whole away from the Nazi Party, while at the same time blaming them for their defeat (individuals supporting these arguments are commonly called part of the 'Hitler Lost Us The War' group). While this self-serving approach was noticed at the time,[14] it was still generally accepted as the closest version of the truth. The end result was a commonly held picture of the Heer being the superior army, ground down by the vast numbers of the 'Bolshevik horde' and betrayed by the stupidity of Hitler. Not only did this ignore Hitler's talent as a military leader, an erratic talent that was sometimes brilliantly incisive and sometimes grossly in error, it also severely undervalued the remarkable transformation of the Soviet armed forces, especially the Red Army (RKKA), from the timid, conservative force of 1941 to an effective war-winning organisation.

After the fall of the wall, Western historians were suddenly exposed to the vast number of Soviet records of the time. This has led to an explosion of the works on the subject, most notably by Richard Overy, David Glantz and Antony Beevor. These historians emphasised the brutality of Stalin's regime, the recovery of the USSR and the RKKA in 1942 and the courage and abilities of the average Russian soldier, relying heavily on Soviet archival material to do so.

Davies

Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory was written by the English historian Norman Davies, best known for his books on Poland. Davies argues although the war was over for 60 years that a number of misconceptions about the war are still common and then sets out to correct them. Two of his main claims are that contrary to popular belief in the West, the dominant part of the conflict took place in Eastern Europe between the two totalitarian systems of the century, communism and fascism; and that Stalin's USSR was as bad as Hitler's Germany.[15] The subtitle No Simple Victory does therefore not just refer to the losses and suffering the allies had to endure in order to defeat the enemy, but also the difficult moral choice the Western democracies had to make when allying themselves with one criminal regime in order to defeat another.[16]

Holocaust denial

A field of pseudohistory has emerged which attempts to deny the existence of the Holocaust and the mass extermination of Jews in German-occupied Europe. The proponents of the belief, known as Holocaust deniers or "negationists", are usually associated with Neo-Nazism and their views are rejected by professional historians.

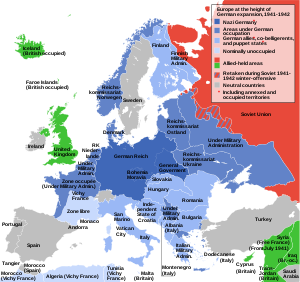

German-occupied Europe

The Nazis perfected the art of stealing, draining the local economies to the maximum or beyord, so that overall production fell.[17]

In all occupied countries resistance movements sprang up.[18] The Germans tried to infiltrate and suppress them, but after the war they emerged as political actors. The local Communists were especially active in promoting resistance movements,[19] as was the British Special Operations Executive (SOE).[20]

Denmark

Denmark's frustrated the Holocaust by slipping almost all of its 7200 Jews into Sweden in 1943.[21][22][23]

Denmark has a large popular literature on the war years that has helped shaped national identity and politics. Scholars have also been active but have much ledd influence on this topic. After the liberation two conflicting narratives emerged. A consensus narrative told how Danes were united in resistance. However there was also a revisionist interpretation which paid attention to the resistance of most Danes, but presented Danish establishment as a collaborating enemy of Danish values. The revisionist version from the 1960s was successfully adopted by the political Left for two specific goals: to blemish the establishment now allied with the "imperialist" United States, and to argue against Danish membership in the European Community. From the 1980s, the Right started to use also used revisionism to attack asylum legislation. Finally around 2003, Liberal Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen started using it as his basic narrative of the war years (partly to legitimize his government's decision to join the war against Iraq in 2003). The occupation has thus played a central role in Danish political culture since 1945, although the role of professional scholars has been marginal.[24]

France

Resistance

The heroism of the French Resistance has always been a favoured topic in France and Britain, with new books in English appearing regularly.[25][26]

Vichy

After 1945 the French ignored or downplayed the role of the Vichy regimer . Since the late 20th century it has become a major research topic.[27]

Collaboration

Collaboration with the Germans was long denied by the French, but since the late 20th century has generated a large literature.[28][29]

Civilian conditions

The roles of civilians,[30] forced labourers and POW's has a large literature.

There are numerous studies of women.[31] [32][33][34]

Alsace Lorraine

Germany integrated Alsace-Lorraine into its German Empire in 1871. France recovered it in 1918. Germany was again in occupation 1940-45. There was widespread material damage. The first wave of destruction in 1940 was inflicted by German forces, the second was caused by Allied bombers in 1944, and the final wave surrounded bitter fighting between German occupiers and American liberators in 1944-1945.[35]

Netherlands

Dutch historiography of World War II focused on the government in exile, German repression, Dutch resistance, the Hunger Winter of 1944-45 and, above all, the Holocaust. The economy was largely neglected. The economy was robust in 1940-41 then deteriorated rapidly as exploitation produced low productivity, impoverishment and hunger.[36]

Norway

The memory of the war seared Norwegians and shaped national policies.[37] Economic issues remain an important topiv.[38][39][40]

Poland

USSR

Popular behaviour has been explored in Byelorussia under the Germans, using oral history, letters of complaint, memoirs, and reports made by the Soviet secret police and by the Communist Party.[41]

References

- ^ Trevor-Roper, Hugh (2011). The Wartime Journals. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1848859906.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (1980). A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 543–547. ISBN 0-06-053034-0.

- ^ Bullock, Alan (1992). Hitler And Stalin: Parallel Lives. New York: Knopf. ISBN 9780771017742.

- ^ R.J.B. Bosworth, "Nations Examine Their Past: A Comparative Analysis of the Historiography of the" Long" Second World War." History Teacher 29.4 (1996): 499-523. in JSTOR

- ^ Rigg, Brian Mark (2005). The Rabbi Saved by Hitler's Soldiers: Rebbe Joseph Isaac Schneersohn and His Astonishing Rescue. University Press of Kansas. pp. 11–35 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Uldricks, Teddy J. (2009). History and Memory. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 60–82 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Tim Cook, Clio's Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars (UBC Press, 2011).

- ^ Gordon Martel, ed. Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered (2nd ed. 2002) p 1.

- ^ James S. Wood, "A Historical Debate of the 1960s: World War II Historiography-The Origins of the War, AJP Taylor, and his Critics." Australian Journal of Politics & History 26.3 (1980): 403-410.

- ^ For historiographical overviews see Martin S. Alexander, "The fall of France, 1940." Journal of Strategic Studies 13#1 (1990): 10–44; Joel Blatt, ed. The French Defeat of 1940: Reassessments (1997); John C. Cairns, "Along the Road Back to France 1940" American Historical Review 64#3 (1959) pp 583–603; John C. Cairns, "Some Recent Historians and the" Strange Defeat" of 1940." Journal of Modern History 46#1 (1974): 60–85; Peter Jackson, "Returning to the fall of France: Recent work on the causes and consequences of the 'strange defeat' of 1940." Modern & Contemporary France 12#4 (2004): 513–536; and Maurice VaÏsse, Mai-Juin 1940: Défaite française, victoire allemande sous l’oeil des historiens Étrangers (2000).

- ^ Martin S. Alexander, "The Fall of France, 1940" in John Gooch, ed. (2012). Decisive Campaigns of the Second World War. p. 10.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Marc Bloch, Strange Defeat: a Statement of Evidence Written in 1940 (Oxford U.P., 1949), p 36

- ^ Carole Fink, "Marc Bloch and the drôle de guerre Prelude to the '"Strange Defeat'" p 46

- ^ Clark, Alan. Barbarossa. Penguin Group (USA) Incorporated, 1966. ISBN 0-451-02848-1

- ^ Gordon, Philip H. (2007). "Europe at War, 1939-1945: No Simple Victory; Europe East and West". Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2006). Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. London: Macmillan. pp. 63–67. ISBN 9780333692851.

- ^ Hans Otto Frøland, Mats Ingulstad, and Jonas Scherner. "Perfecting the Art of Stealing: Nazi Exploitation and Industrial Collaboration in Occupied Western Europe." in Industrial Collaboration in Nazi-Occupied Europe (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016). 1-34.

- ^ Ben Shepherd nd Juliette Pattinson. "Partisan and Anti-Partisan Warfare in German-Occupied Europe, 1939–1945: Views from Above and Lessons for the Present." Journal of Strategic Studies 31.5 (2008): 675-693.

- ^ Tony Judt, Resistance and revolution in Mediterranean Europe, 1939-1948 (1989).

- ^ M.R.D. Foot, SOE: The Special Operations Executive, 1940-1946 (London: Pimlico, 1999).

- ^ Tatiana Brustin-Berenstein, "The historiographic Treatment of the abortive Attempt to deport the Danish Jews." Yad Vashem Studies 17 (1986): 181-218.

- ^ Gunnar S. Paulsson, "The 'Bridge over the Øresund: The Historiography on the Expulsion of the Jews from Nazi-Occupied Denmark." Journal of Contemporary History 30.3 (1995): 431-464. in JSTOR

- ^ Hans Kirchhoff, "Denmark: A Light in the Darkness of the Holocaust? A Reply to Gunnar S. Paulsson," Journal of Contemporary History 30#3 (1995), pp. 465-479 in JSTOR

- ^ Nils Arne Sørensen, "Narrating the Second World War in Denmark since 1945." Contemporary European History 14.03 (2005): 295-315.

- ^ Robert Gildea, Fighters in the Shadows: A New History of the French Resistance (2015).

- ^ Olivier Wieviorka, The French Resistance (Harvard UP, 2016).

- ^ Henry Rousso and Arthur Goldhammer, The Vichy syndrome: History and memory in France since 1944 (Harvard Univ Press, 1994).

- ^ Philippe Burrin, France under the Germans: Collaboration and Compromise 1996).

- ^ Bertram M. Gordon, Collaborationism in France during the Second World War (Cornell UP, 1980).

- ^ Richard Vinen, Unfree French: Life under the Occupation (2006)

- ^ Hanna Diamond, Women and the Second World War in France, 1939-1948: choices and constraints (2015).

- ^ Sarah Fishman, We Will Wait: Wives of French Prisoners of War, 1940–1945 (Yale UP, (1991).

- ^ Miranda Pollard, Reign of Virtue: Mobilizing Gender in Vichy France (U of Chicago Press, 1998).

- ^ Francine Muel-Dreyfus, Kathleen A. Johnson, eds., Vichy and the Eternal Feminine: A Contribution to a Political-Sociology of Gender (Duke UP, 2001). <ref<Paula Schwartz, "Partisianes and Gender Politics in Vichy France". French Historical Studies (1989). 16#1: 126–151. doi:10.2307/286436. JSTOR 286436.

- ^ Hugh Clout, "Alsace–Lorraine/Elsaß–Lothringen: destruction, revival and reconstruction in contested territory, 1939–1960." Journal of Historical Geography 37.1 (2011): 95-112.

- ^ Hein A.M. Klemann, "Did the German Occupation (1940–1945) Ruin Dutch Industry?." Contemporary European History 17#4 (2008): 457-481.

- ^ Clemens Maier, "Making Memories The Politics of Remembrance in Postwar Norway and Denmark." (Doctoral Dissertation European University Institute, 2007) online Bibliography pp 413-34.

- ^ Harald Espeli, "Economic Consequences Of The German Occupation Of Norway, 1940–1945." Scandinavian Journal of History 38.4 (2013): 502-524.

- ^ Rodney Allan Radford, "The Ordinariness of goodness: Myrtle Wright and the Norwegian non-violent resistance to the German occupation, 1940-1945" (Diss. University of Tasmania, 2015).online

- ^ Hans Otto Frøland, Mats Ingulstad, Jonas Scherner, eds. Industrial Collaboration in Nazi-Occupied Europe: Norway in Context (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016).

- ^ Franziska Exeler, "What Did You Do during the War?" Kritika: Explorations in Russian & Eurasian History (Fall 2016) 17#4 pp 805-835.

Further reading

- Ballinger, Pamela. "Impossible Returns, Enduring Legacies: Recent Historiography of Displacement and the Reconstruction of Europe after World War II." Contemporary European History 22#1 (2013): 127-138.

- Bosworth, R. J. B. "Nations Examine Their Past: A Comparative Analysis of the Historiography of the 'Long' Second World War." History Teacher 29.4 (1996): 499-523. in JSTOR

- Bosworth, R. J. B. Explaining Auschwitz and Hiroshima: History Writing and the Second World War 1945-1990 (Routledge, 1994) online

- Bucur, Maria. Heroes and victims: Remembering war in twentieth-century Romania (Indiana UP, 2009).

- Chirot, Daniel, ed. Confronting Memories of World War II: European and Asian Legacies (U of Washington Press, 2014).

- Cook, Tim. Clio's Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars (UBC Press, 2011).

- Dreisziger, Nándor F., ed. Hungary in the Age of Total War (1938-1948) (East European Monographs, 1998).

- Edele, Mark. "Toward a sociocultural history of the Soviet Second World War." Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 15.4 (2014): 829-835.

- Edwards, Sam. Allies in Memory: World War II and the Politics of Transatlantic Commemoration, c. 1941–2001 (Cambridge UP, 2015).

- Horton, Todd A., and Kurt Clausen. "Extending the History Curriculum: Exploring World War II Victors, Vanquished, and Occupied Using European Film." History Teacher 48.2 (2015). online

- Keshen, Jeffrey A. Saints, Sinners, and Soldiers: Canada's Second World War (UBC Press, 2007).

- Killingray, David, and Richard Rathbone, eds. Africa and the Second World War (Springer, 1986).

- Kivimäki, Ville. "Between defeat and victory: Finnish memory culture of the Second World War." Scandinavian Journal of History 37.4 (2012): 482-504.

- Kochanski, Halik. The eagle unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War (Harvard UP, 2012).

- Kohn, Richard H. "The Scholarship on World War II: Its Present Condition and Future Possibilities." Journal of Military History 55.3 (1991): 365.

- Kushner, Tony. "Britain, America and the Holocaust: Past, Present and Future Historiographies." Holocaust Studies 18#2-3 (2012): 35-48.

- Lagrou, Pieter. The Legacy of Nazi Occupation: Patriotic Memory and National Recovery in Western Europe, 1945-1965 (1999). focus oin France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

- Lebow, Richard Ned et al eds. The Politics of Memory in Postwar Europe (2006).

- Lee, Loyd E. and Robin Higham, eds. World War II in Asia and the Pacific and the War's aftermath, with General Themes: A Handbook of Literature and Research (Greenwood Press, 1998) online

- Lee, Loyd E. and Robin Higham, eds. World War II in Europe, Africa, and the Americas, with General Sources: A Handbook of Literature and Research (Greenwood Press, 1997) online

- Maddox, Robert James. Hiroshima in History: The Myths of Revisionism (University of Missouri Press, 2007) online

- Martel, Gordon ed. Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered (2nd ed. 2002) online

- Mitter, Rana. "Old ghosts, new memories: China's changing war history in the era of post-Mao politics." Journal of Contemporary History (2003): 117-131. in JSTOR

- Morgan, Philip. The fall of Mussolini: Italy, the Italians, and the second world war (Oxford UP, 2007).

- Overy, Richard James. The Origins of the Second World War (Routledge, 2014).

- Parrish, Michael. "Soviet Historiography of the Great Patriotic War 1970-1985: A Review." Soviet Studies in History 23.3 (1984)

- Rasor, Eugene. The China-Burma-India Campaign, 1931-1945: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography (Greenwood Press, 1998) online

- Rasor, Eugene. The Southwest Pacific Campaign, 1941-1945: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography (Greenwood Press, 1996) online

- Schumacher, Daniel. "Asia's ‘Boom’of Difficult Memories: Remembering World War Two Across East and Southeast Asia." History Compass 13.11 (2015): 560-577.

- Shaffer, Robert. "G. Kurt Piehler, Sidney Pash, eds. The United States and the Second World War: New Perspectives on Diplomacy, War, and the Home Front (Fordham University Press, 2010).

- Stenius, Henrik, Mirja Österberg, and Johan Östling, eds. Nordic Narratives of the Second World War: National Historiographies Revisited (2012).

- Stone, Dan. Historiography of the Holocaust (2004) 573p.

- Summerfield, Penny. Reconstructing women's wartime lives: discourse and subjectivity in oral histories of the Second World War (Manchester University Press, 1998); emphasis on Britain.

- Thonfeld, Christoph. "Memories of former World War Two forced labourers-an international comparison." Oral History (2011): 33-48. in JSTOR

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. A world at arms: A global history of World War II (Cambridge UP, 1995).

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. "World War II scholarship, now and in the future." Journal of Military History 61.2 (1997): 335+.

- Wolfgram, Mark A. Getting History Right": East and West German Collective Memories of the Holocaust and War (Bucknell University Press, 2010).

- Wood, James S. "A Historical Debate of the 1960s: World War II Historiography‐The Origins of the War, AJP Taylor, and his Critics." Australian Journal of Politics & History 26.3 (1980): 403-410.