History of Wrexham

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

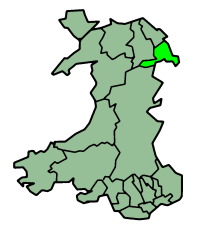

The history of Wrexham from the prehistoric to the present day. Wrexham is a large town in the north-east of Wales with a long history of both heavy industry and as a market town.

Prehistoric to Roman times

Approximately 8,000 years ago Mesolithic man ventured to what is now the Wrexham area. These people were hunter-gatherers and led a nomadic existence. They left little tangible evidence of their existence, save a number of small flint tools called microliths that have been found in the Borras area.[1]

A number of Neolithic (4300 - 2300 BC) stone axe heads have been found in Borras, Darland and Johnstown.

Two Bronze age mounds are situated within the town at Fairy Mount, Fairy Road and Hillbury on Hillbury Road. Both of these mounds lie within the grounds of Victorian properties in the south west of the town. It is likely that construction work within this area during the early 20th century eradicated other related features. The Acton Park Hoard[2] of skilfully made early Middle Bronze Age axe heads found in Wrexham suggests that this area was a centre for advanced and innovative metalworking industry.

The area surrounding Wrexham is well served by several rivers, including the Clywedog, Alyn and Gwenfro, all of which are tributaries of the Dee. These rivers would have served as highways for early man. Finds within the Alyn area reveal that trade was taking place along this river with places as far away as Ireland during the Bronze Age.

A number of Iron Age hillforts also exist within the surrounding area, perhaps marking a tribal boundary. These include Bryn Alyn (near Bradley), Y Gaer (near Broughton, Flintshire) and Y Gardden (near Ruabon).

At the time of the Roman conquest of Roman Britain, the area which Wrexham formed part of was held by a tribe called the Cornovii. The Cornovii held the lowland forests of Cheshire and Shropshire. Their tribal capital was at Wroxeter, near Shrewsbury. The original hill fort hillfort capital of the tribe was located on the Wrekin hill and one theory for the origins of the name ‘Wrexham’ is that it developed as a description of a settlement of men from the neighbourhood of the Wrekin: the ‘Wrocansaetan’ or ‘Wreocensaetan’.

In 48 A.D the Roman Legions reached Wroxeter and then proceeded to attack a tribe called the Deceangli who were based in what is now Flintshire. Around 70 - 75 A.D the Legionary fortress of Deva was constructed (modern-day Chester) and for the next 300 years was the home of the Twentieth Legion.

Evidence of Roman occupations can be found at nearby Holt, where a tile and pottery works were constructed on the banks of the River Dee and at Ffrith where the remains of buildings have been located. In recent years evidence of Roman occupation nearer the town centre, was found during the construction of the Plas Coch retail park. In 1995 further construction work on the site revealed traces of Roman field boundaries, hearths, a corn drying kiln and coins from the period c. AD150 –350. It is thought that these are the remains of a farmstead.

Mercian conquest

Wrexham formed part of the Romano-British Kingdom of Powys which emerged following the end of Roman rule in Britain and extended from the Cambrian mountains to the west to the modern west midlands region of England to the east. The dedication at Worthenbury to the 5th-century Bishop of Bangor St Deiniol suggests that this area was one of his outlying estates.

Towards the end of the 6th century English settlers were penetrating along the upper Trent and laying the foundations of the kingdom of Mercia. A Latinisation of the Old English Mierce meaning ‘border people’. Possibly by the early 7th century some English had settled peacefully on surplus lands in the border region and gradually the line connecting Tarvin and Macefen along the river Gowy and Broxton Hills in Cheshire could have formed the dividing line between the British (Welsh) and the English during the 7th century.

In 616 Aethelfrith of Northumbria defeated the combined forces of Gwynedd and Powys at the Battle of Chester and the royal Cynddylan dynasty of Powys was overthrown by the Mercians at the end of the 7th century. The English went on to dominate north-east Wales from the 8th to 10th centuries.

During the 8th century the royal house of Mercia displayed militaristic dominance and took advantage of the weakness of Powys to push their frontiers westwards. In 796 a battle between the Welsh and Mercians was fought at Rhuddlan and in the 8th century the Mercians established the earth boundaries of Wat’s Dyke and Offa’s Dyke between the Welsh kingdom of Powys and the English kingdom of Mercia. These boundaries pass just to the west of the site of Wrexham suggesting that during the 8th century the area lay within the bounds of Mercia.

In the 8th century, the settlement of Wrexham was likely founded by Mercian colonists from the Midlands during this first advance. The settlement was founded on the flat ground above the meadows of the River Gwenfro which would have provided high-quality grazing for animals. The etymological origins of the name ‘Wrexham’ may possibly be traced back to this period as being derived from an Old English personal name, ‘Wryhtel’ and ‘hamm’ meaning water meadow or enclosure within the bend of a river i.e. Wryhtel’s meadow. The district was known in English as Bromfield.

Despite the establishment of Anglo-Saxon political control across the Marcher region in the 7th century there is little evidence to support the idea of a substantial English folk movement into the region during the 7th or 8th centuries. The overall Anglo-Saxon occupation of the Wrexham area seems to have been partial for while Wrexham and a number of surrounding settlements have seemingly English names, the names of fields in the area were predominantly Welsh until the beginning of the 20th century.

Welsh restoration and border conflict

Renewed Welsh and Viking attacks led to a contraction in English power in north Wales in the early-10th century yet English kings seem to have nominally dominated the area till the reign of Ethelred II (978-1016).

The English dominance in north Wales further declined with the rise of Gruffudd ap Llewellyn who was recognised as King of Wales by Edward the Confessor in 1056 and likely took control of all the land to the west of the River Dee, including Wrexham. The Welsh remained in possession of the Wrexham area at the time of the taking of the Domesday Survey of 1086 and the settlement is therefore not mentioned in the survey.

The boundary of Offa’s Dyke lost its significance and between 1086 and 1277 the Wrexham areas formed part of the native Welsh lordship of Maelor. The Lords of Maelor had their seat at Dinas Bran and their lands stretched north from Dinas Bran to beyond Marford with the Dee as their eastern boundary and the uplands of Hope as their western limits. The lordship was divided into two commotes each with their Maerdrefi (chief manors) at Wrexham and Marford respectively. The Wrexham commote (cymwd) was formed of the greater part of Bromfield and became known as ‘Maelor Cymraeg’ (‘Welsh Maelor’).

Under the lordship of Maelor, Welsh law was enforced in Wrexham by Welsh officials and Welsh customs prevailed. Palmer describes the area as being ‘thoroughly Cymricized’ with the English inhabitants being ‘either slain, expelled or absorbed’. The Welsh re-colonisation of the border region is likely to have taken place either as a result of the forward policy of the Princes of Powys, or by a process of peaceful penetration directly encouraged by Norman lords who wished to colonise lands devastated in the course of the Norman conquest.

The lordship remained disputed between the Welsh and English during the 12th century. The annals of Chester state that the castle of Bromfield (the English name for Maelor) was burned by the English in 1140 and the King Henry II pipe roll of 1161 records that a Norman motte and bailey castle is present at 'Wristlesham', the first recorded reference to the town. The castle was likely to have been located in the Erddig area on the southern outskirts of Wrexham and founded around 1150 by Hugh de Avranches, earl of Chester.

Henry II himself led his forces up the Ceiriog Valley in 1165 but was defeated by Welsh forces led by Owain Gwynedd at the Battle of Crogen. However the Chronicle of St Werburgh’s Chester records that that in 1177 Earl Hugh of Chester had conquered the whole of Bromfield. Any English advance ultimately proved temporary however as the area was re-conquered by the Welsh Princes of Powys and was undisputedly in the hands of the house of Powys Fadog in the early years of the 13th century.

The princes of Powys skilfully dealt with their belligerent neighbours, Gwynedd and England, and the stability allowed Wrexham to develop as a trading town and administrative centre of the cwmwd (commote). In 1202 Madog ap Gruffydd Maelor, Lord of Dinas Brân, granted to his newly founded Cistercian abbey of Valle Crucis some of his demesne lands in ‘Wrechcessham’. In 1220, the earliest reference of Wrexham Parish Church is made when it is mentioned with reference to the bishop of St Asaph, who gave the monks of Valle Crucis in nearby Llangollen half of the income of the Church in Wrexham.

In 1276 Madog II ap Gruffydd, Prince of Powys Fadog and Lord of Dinas Brân, did homage to Edward I and his tenants were received into the king’s peace. When Madoc II ap Gruffydd died in 1277 his estates were taken over by the Crown to be administered by the king in trust for the prince’s two infant sons. In 1281 the two boys went missing and are traditionally speculated to have been drowned under the orders of the Norman John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, who was a leading supporter in Edward I’s Welsh campaigns.

In 1282 Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, prince of Wales was killed, Wales lost its independence and John de Warenne was granted the lordships of Bromfield (Maelor) and Yale (derived from the neighbouring cantref of Iâl) by King Edward I in 1282. The tensions of this period are revealed by the suggestion that in 1282 the men of Bromfield needed the King’s protection if they were to pass without molestation to and from the markets of Chester and Oswestry and Edward I himself is reported to have briefly stayed at Wrexham during his expedition to suppress the revolt of Madoc Ap Llewellyn in 1294.

18th and 19th centuries

In the 18th century Wrexham was known for its leather industry with skinners and tanners in the town. The horns from cattle were used to make things like combs and buttons. There was also a nail making industry in Wrexham but in the mid-18th century Wrexham was no more than a small market town with a population of perhaps 2,000.

In the late 18th century Wrexham was transformed by the coming of the industrial revolution. It began when the famous entrepreneur John Wilkinson (1728–1808) known as 'Iron Mad Wilkinson' opened Bersham Ironworks in 1762. In 1793 he opened a smelting plant at Brymbo.

Wrexham gained its first newspaper in 1848. Market Hall was built in 1848. In 1863 a volunteer fire brigade was founded.

In 1849 Wrexham was described as:

- "A market town, a parliamentary borough, the head of a Union, and a parish, chiefly in the hundred of Bromfield, county of Denbigh; 26 miles (SE by E) from Denbigh, 18 (ESE) from Ruthin, and 187½ (NW) from London; ..... and containing 12,921 inhabitants, of whom 5818 are in the townships of Wrexham Abbot and Wrexham Regis, forming the town."[3]

Wrexham benefitted from good underground water supplies which was essential to the brewing of good beer and brewing became one of its main industries. in the middle of the 19th century, there were 19 breweries in and around the town[4] Several of these were comparatively large breweries, together with many smaller breweries situated at local inns. Some of the more famous old breweries were the Albion, Cambrian, Eagle, Island Green, Nag's Head (Soames) and Willow.

However, the most famous was the Wrexham Lager brewery which was built between 1881 and 1882 in Central Road. This was the first brewery to be built in the United Kingdom to produce lager beer. Another major producer, Border Breweries, was formed in 1931 by a merger of Soames, Island Green, and the Oswestry firm of Dorsett Owen.

Wrexham is on the edge of the rich Ruabon area marl beds[5] and several brickworks sprang up in the area, among these, the most well known was Wrexham Brick and Tile and Davies Brothers in Abenbury, on the outskirts of Wrexham.

Coal mining was an important industry in the area, and provided employment for large numbers of Wrexham people, however most of the mines were situated well outside of the town. Wrexham's coal field was part of the larger North East Wales field. A number of deep mines were constructed throughout the area including Llay, Gresford, Bersham and Johnstown. A number of new settlements were built on the edge of the town to accommodate miners at a number of the sites including Llay and Pandy (for Gresford).

Other forms of mining and quarrying have taken place around Wrexham throughout its history, these include lead extracted from Minera.

Wrexham was connected to the rest of the UK by rail in 1849 and this eventually became a large and complex network of railways, the main branch being the Wrexham and Minera Branch, which supported the steelworks at nearby Brymbo Steel Mill and the Minera Limeworks. In 1895, the Wrexham and Ellesmere Railway was completed[6] and cut a swathe through the town centre.

20th and 21st centuries

In the latter half of the 20th century, Wrexham began a period of depression: the many coal mines closed first, followed by the brickworks and other industries, and finally the steelworks (which had its own railway branch up until closure) in the 1980s. Wrexham faced an economic crisis. Many residents were anxious to sell their homes and move to areas with better employment prospects, however buyers were uninterested in an area where there was little prospect of employment. Many home-owners were caught in a negative equity trap. Wrexham was suffering from the same problems as much of Industrialised Britain and saw little investment in the 1970s.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Welsh Development Agency (WDA) intervened to improve Wrexham's situation: it funded a major dual carriageway called the A483 bypassing Wrexham town centre and connecting it with Chester and Shrewsbury, which in turn had connections with other big cities such as Manchester and Liverpool. It also funded shops and reclaimed areas environmentally damaged by the coal industry. The town centre was regenerated and attracted a growing number of high street chain stores. However, the biggest breakthrough was the Wrexham Industrial Estate, previously used in the Second World War, which became home to many manufacturing businesses including Kellogg's, JCB, Duracell and Pirelli. It is now the fifth largest industrial estate in Europe (second in UK) by area[citation needed] with over 250 businesses[citation needed]. There are also a number of other large industrial estates in the Wrexham area, with companies such as Sharp, Brother, Cadbury, and Flexsys.

On 21 November 2012, Brother made the last British typewriter at its Wrexham factory.[7]

Economy

In November 2006 unemployment in Wrexham stood at 1.9%. This was below the averages for Wales of 2.3%, and England and the UK of 2.5%.

Caia Park riot

In June 2003, a large disturbance took place in the Caia Park estate, which has become known as The Caia Park Riots. Tension developed between Iraqi Kurds and some locals centred on one of the estates' pubs (The Red Dragon, Wrexham), which gradually escalated and resulted in petrol bombs and other missiles being hurled at police trying to restore order.[8][9][10]

Developments and regeneration

Recent years have seen a large amount of redevelopment in Wrexham's town centre. The creation and re-development of civic and public areas such as Queens Square, Belle Vue Park and Llwyn Isaf have improved the area dramatically. New shopping areas have been created at Henblas Square, Island Green and Eagles Meadow.

The bid for city status

Wrexham is the largest settlement in North Wales, and has applied for city status several times, most recently in 2002 as part of the celebrations for the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II. Other Welsh applicants were Aberystwyth, Machynlleth, Newtown, Newport and St Asaph. The local authority cited the following claims as to why Wrexham should be granted city status:

- The town is the largest urban area north of the Brecon Beacons

- Despite not having a Protestant cathedral (one of the historical criteria for city status), it is home to one of only three Roman Catholic cathedrals in Wales

- It is the centre for education, culture, retail, industry and business in North Wales

- It has the largest catchment (in terms of area) of any other major Welsh settlement

- The town has a long and proud history of industry, including coal mining, steelmaking, brewing and tanning.

- It has recently transformed from an historic market town and industrial hub into a forward-thinking business and manufacturing centre (including one of the largest industrial estates in Europe)

- The population of the conurbation surrounding the town is over 100,000 people

In the end, the Welsh award was given to Newport in South Wales, however the borough still holds out hope of gaining the status in the near future.

Wrexham, again applied in 2012 as part of the Diamond jubilee. However lost out to St Asaph. With a population of only 3142 making it only the second smallest city in the UK.

References

- ^ "Borras Dig" (PDF). www.cpat.org.uk. CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST.

- ^ Casglu'r Tlysau - Gathering the Jewels. Casglu'r Tlysau - Gathering the Jewels http://education.gtj.org.uk/en/item1/25839. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Wales, 1849

- ^ BBC History % March 2010 [1] (Retrieved 2011-01-06)

- ^ Penmorfa.com [2] Retrieved 2011-0106)

- ^ CPAT [3] (Retrieved 2011-01-06)

- ^ Saner, Emine (2012-11-21). "Last British Made Typewriter". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Police officers injured in new Wrexham violence". The Guardian. London. 2003-06-24.

- ^ Davies, Wyre (2003-06-24). "Complex truth behind Wrexham riots". BBC News.

- ^ Bunyan, Nigel (2003-06-25). "Football thugs 'led attack on Kurd refugees'". The Daily Telegraph. London.