History of Yarmouth, Maine

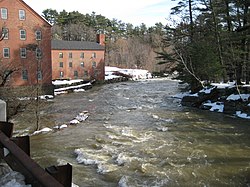

The history of Yarmouth, Maine, is closely tied to its position on the banks of the Royal River and its proximity to Casco Bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Maine, itself a gulf of the Atlantic Ocean.

Native Americans originally settled the area, and several wars between them and later European settlers occurred before they were driven from the area for the final time in the mid-18th century.

Around three hundred sea-going vessels were built in the numerous shipyards in Yarmouth harbor from around 1790 to 1890, while almost sixty mills were founded over 250 years along the town's section of the Royal River, making use of its four waterfalls for power.

The Maine Historic Preservation Commission[1] has found many of Yarmouth's historic buildings eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places,[2] in addition to the twelve that are already included.

Early settlers[edit]

Traces of human occupation in the Yarmouth area date to about 2,000 BC. During the years prior to the arrival of the Europeans, many Native American cultures existed in the area,[3] largely because of the natural features of the coastal land. Rivers provided several resources, including food, fertile soil, power for the mills and the navigability between the inland areas and the ocean.[4]

In 1643, Englishman George Felt, who had emigrated to Charlestown, Massachusetts Bay Colony, eighteen years earlier, purchased 300 acres of land at Broad Cove from John Phillips (1607–c. 1667), a Welshman, and thus became one of the first European settlers in Yarmouth. (His family in Bedfordshire, England, went by the family name Felce. He called himself George Felch, however, when he moved to America. He began to be known as George Felt in his later years.)[5]

Englishman William Royall (c. 1595–1676),[6] a cooper, emigrated to Salem, Massachusetts Bay Colony, in July 1629, aboard the Lyon's Whelp. He was a servant in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Company, and after serving his seven years, he was provided with a land grant in the Casco Bay area of Maine. In 1636, he purchased a farm at what is now the upscale Lambert Point, next to Redding Creek, at the southern tip of Lambert Road, where he lived with his wife, County Durham native Phoebe Green. They had thirteen children together between 1639 and 1657, the first being son William Jr.[5]

The Royal River has ever-since borne an alternative spelling of Royall Sr.'s name, though two streets off Gilman Road — Royall Meadow Road and Royall Point Road — carry the double-L spelling. (One of the earliest maps naming the river Royal was a 1699 map by Wolfgang William Romer on which it was spelled "Roiall River.")[6] This stream and its vicinity were called by the Indians "Westcustogo" — a name that, until the early 1990s, was preserved by an inn of the same name on Princes Point Road at its intersection with Lafayette Street.[7] (The building remains but it is now occupied by another business.)

John Cousins (c. 1596–1682), a native of Wiltshire, England, had arrived a year or more earlier than Royall, with his wife, Mary, occupying the neck of land between the branches of the Cousins River and Cousins Island.[8]

By 1676, approximately sixty-five people lived in Westcustogo. Soon after, however, conflicts forged by King Philip's War (1675–1678) caused them to abandon their homes and move south.[3] John Cousins was injured and went to York, Maine, to receive treatment. He died in Cider Hill, York County, in 1682, aged 86. He deeded his real estate in Casco Bay to his wife.[5]

Some settlers returned to their dwellings in 1679, and within twelve months the region became incorporated as North Yarmouth, the eighth town of the Province of Maine.[5]

In 1684, an English military officer named Walter Gendall claimed to own all of Felt's two thousand acres in Casco Bay. He had purchased one hundred acres from him in 1680.[9] Gendall had emigrated to America from Cornwall around 1640.[9]

In 1688, during the early stages of King William's War, also known as the Second Indian War (1688–1697), while the inhabitants on the southern side of the river were building a garrison, they were attacked by Indians, and attempted a defense. They continued the contest until nightfall, when the Indians retired. It was not long before they appeared again, in such force that the thirty-six families of the settlement were forced to flee, abandoning their homes for a second time. Walter Gendall, who had been on good terms with the Indians, was killed.[9]

The unrest kept the area deserted for many years, but by 1715 settlers revisited their homes, by which point they found their fields and the sites of their habitations covered by a young growth of trees. The mills at the First Falls were rebuilt first.[5]

In 1722, a "Committee for the Resettlement of North Yarmouth" was formed in Boston, Province of Massachusetts Bay.[5]

In 1725, Massachusetts natives William and Matthew Scales were killed at the hands of the Indians. William's wife and daughter, both named Susannah, survived. His daughter married James Buxton the same year. They are both buried in the Ledge Cemetery.[5]

Joseph Felt, son of Moses Felt II, also perished. His wife, Sarah (Mills), and children were taken into captivity for five years. One of the captors remarked to Felt's widow: "Husband much tough man! Shot good many times, no die! Take scalp off alive; then take knife and cut neck long 'round."[10] Joseph Felt's daughter and George Felt's great-granddaughter, Sarah, married in 1720 Captain Peter Weare, who recovered the family in some woods near Quebec. He later drowned while crossing the river near his home. The captain's son and Joseph Felt's brother-in-law, Joseph Weare, became a noted scout, pursuing the Native Americans at every opportunity until his death during a trip to Boston sometime after 1774. His widow, Mary Noyes, remarried, to Humphrey Merrill of Falmouth.[5]

Once resettlement began, in 1727, the town's population began to grow rapidly. A proprietors' map was drawn up. It surveyed land divisions made with 103 original proprietors, each with a home lot of ten acres. If this lot was occupied and improved, the settler was permitted to apply for larger after-divisions.[5]

The structural frame of the first meetinghouse, the Meetinghouse under the Ledge, was raised in 1729 near Westcustogo Hill on what is now Gilman Road, and nine years later the first school was built at the northwestern corner of the Princes Point Road intersection.[5]

North Yarmouth held its first town meeting on May 14, 1733.[5]

In August 1746, a party of thirty-two Indians secreted themselves near the Lower Falls for the apparent purpose of surprising Weare's garrison, in the process killing 35-year-old Philip Greely, whose barking dog blew their cover.[5] His wife was Hannah. Their son, Captain Jonathan Greeley, died in an engagement with a British frigate off Marblehead, Massachusetts, in 1781. He was 39. Hannah remarried, to Jonathan Underwood.[5]

In June 1748,[11] a large party of Indians surprised four people near the meetinghouse. They killed the elderly Ebenezer Eaton.[5]

Joseph Burnell was the only inhabitant of the town to be killed at the hands of the Indians in 1751. He had been on horseback near the Presumpscot River falls when he was ambushed and shot. He was found scalped, with his steed lying nearby, having been shot four times.[5] He left behind a wife and 14-year-old daughter, both named Sarah.

In 1756, Indians attacked the Means family, who lived at Flying Point. The family consisted of Thomas, his wife Alice, daughters Alice and Jane,[12] an infant son, Robert, and Molly Finney, sister of the patriarch and aged about sixteen. The family was dragged out of their home. Thomas was shot and scalped. Mother and baby ran back into the house and barricaded the door. One of the attackers shot through a hole in the wall, killing the infant and puncturing his mother's breast. John Martin, who had been sleeping in another room, fired at them, causing them to flee. They took with them Molly, whom they made follow them through the woods to Canada. Upon her arrival in Quebec, she was sold as a slave. A few months later, Captain William McLellan, of Falmouth, was in Quebec in charge of a group of prisoners for exchange. He had known Molly before her capture and secretly arranged for her escape. He came below her window and threw her a rope which she slid down. McLellan brought her back to Falmouth on his vessel. They married shortly afterwards.[5] Alice remarried, to Colonel George Rogers. Thomas is interred in Freeport's First Parish Cemetery, alongside his son. His wife is buried with her second husband in Flying Point Cemetery.

The Means massacre was the last act of resistance by the indigenous people to occur within the limits of the town.[5]

By 1764, 1,098 individuals lived in 154 houses. By 1810, the population was 3,295. During a time of peace, settlement began to relocate along the coast and inland.[3]

The town's Main Street gradually became divided into the Upper Village (also known as the Corner) and Lower Falls, the split roughly located around the present-day U.S. Route 1 overpass (Brickyard Hollow, as it was known). Among the new proprietors at the time were descendants of the Plymouth Pilgrims.[5]

The Yarmouth Village Improvement Society has added wooden plaques to over 100 notable buildings in town. These include:[13][14]

- Cushing and Hannah Prince House, 189 Greely Road — built 1785. This Federal-style farmhouse remained the home of several generations of the Levi and Olive Prince Blanchard family from 1832 to 1912

- Mitchell House, 333 Main Street — circa 1800. Another Federal-style building, with an unusual steeply-pitched hip roof, it was the home of three doctors — Ammi Ruhamah Mitchell, who died "suddenly" in 1824, aged 62, Gad Hitchcock and Eleazer Burbank

- Capt. S. C. Blanchard House, 317 Main Street — 1855. One of the most elaborate and finely-detailed Italianate residences on the Maine coast, it was built by Sylvanus Blanchard (1778–1858),[15] a highly successful shipbuilder. The design is by Charles A. Alexander, who also executed the Chestnut Street Methodist Church in Portland. It replaced a building that is pictured in the oldest image (a drawing) of a Yarmouth street scene, drawn between 1837 and 1855[16]

- Captain Rueben Merrill House, 233 West Main Street — 1858. Thomas J. Sparrow, the first native Portland architect, designed this three-storey Italian-style house. Merrill was a well-known sea captain, who went down with his ship off San Francisco in 1875. Few changes have been made in the building, because it did not leave the possession of the Merrill family between then and 2011

Another notable building is Camp Hammond (1889–90), at 275 Main Street, whose construction method is significant in that the building consists of a single exterior wall of heavy planks over timbers, with no hidden spaces or hollow walls. This so-called mill-built construction was used largely for fire prevention.[13] It was built by George W. Hammond. Frederick Law Olmsted, who is responsible for the layout of New York's Central Park, designed the landscape for the exterior.[17]

A "grasshopper plague" arrived in 1822, which resulted in the loss of wheat and corn crops.[5]

Around 1847, the Old Ledge School was moved from Gilman Road to today's Maine State Route 88, at the foot of the hill where the West Side Trail crosses the road. A 1975 replica now stands just beyond the brick schools on West Main Street.[5]

Secession from North Yarmouth[edit]

Yarmouth constituted the eastern part of North Yarmouth until 1849. On August 8 of that year, it seceded and incorporated as an independent town. The split occurred due to bickering between the inland, farming-based contingent and the coastal maritime-oriented community. Unable to resolve this difference, the two halves of the town separated into present-day Yarmouth and North Yarmouth.[3]

In 1849 there were nine districts in Yarmouth, designated by numbers: Number One: (Cousins) Island; Number Two: Ledge; Number Three: (Lower) Falls; Number Four: Corner; Number Five: (Princes) Point; Number Six: Greely Road; Number Seven: Pratt; Number Eight: Sweetser; and Number Nine: East (Main). By 1874, however, efforts were made to abolish this setup due its being seen as "unfair" in terms of fund distribution.[5]

By 1850, Yarmouth's population was 2,144, and very little changed over the hundred years that followed.

18th- and 19th-century business relied heavily upon a variety of natural resources. Once lumber was cut and sent to market, the land was farmed. Tanneries were built near brooks; potteries and brickyards put to use the natural clay in the area; and mills flourished along the Royal River, providing services such as iron-forging and fulling cloth.[3]

Shipbuilding[edit]

Maritime activities were important from the beginning of the third settlement. Almost three hundred vessels were launched by Yarmouth's shipyards in the century between 1790 and 1890.[18]

19th-century Yarmouth[edit]

In 1887, a fire started in the dry grass south of Grand Trunk Station by a spark from a passing train. Fanned by a strong wind, it spread rapidly into the woods and up over the ledge. Two hundred acres were burned, and the fire was only stopped because it reached the waters of Broad Cove.[5]

Yarmouth's "town system"[5] went into effect in April 1889. Three of the former districts were discontinued because they were small and had dilapidated buildings. These were Princes Point, Greely Road and the Sweetser district – the last of which was on the Sodom Road (now Granite Street) and the Freeport line.[5]

Electricity came to Yarmouth in 1893.[17]

Into the 20th century[edit]

Another, more menacing fire occurred in April 1900, when the corn-canning factory of Asa York caught fire from a spark blown from the stack of the Walker & Cleaves sawmill. A strong southerly breeze carried the sparks directly across the most thickly settled part of town, causing small fires in various places so that over twenty buildings were burning concurrently.[5]

In 1903, the post office established a route around town for the rural free delivery of mail. Hired was Joshua Adams Drinkwater as the town's first letter carrier. Early in the morning he would leave Princes Point, pick up the mail at Lower Falls, and then deliver letters to the northern edge of town, including Sligo and Mountfort Roads. Around noon, he would pick up the afternoon sack for the town's western and coastal farms. Each day, as he passed his farm on Princes Point Road, he would change horses and eat lunch with his wife, Harriet.[19] They had a daughter, Elizabeth.

In 1918, the Spanish flu hit town in two waves, resulting in 370 infections and fourteen deaths.[17]

In 1923, town historian William Hutchinson Rowe announced that a history of Yarmouth was in the works. The project took fourteen more years to complete, but it was "so thorough that it is still in print".[18] Rowe died in 1955, eighteen years after its publication, aged about 73.[18]

A Grippe epidemic struck the town in January 1944, with two thousand residents placed into quarantine.[20]

In 1949, Yarmouth celebrated its centenary with a parade.[21]

Rapid growth was experienced again after 1948, when Route 1 was put through the town. Two years later, there were 2,699 inhabitants of the town. Interstate 295 was built through the harbor in 1961 (spanning part of the town known as Grantville[22] across to the land between Route 88 and Old Shipyard Road), and the town grew about 40%, from 4,854 residents in 1970 to 8,300 thirty-five years later.

New millennium[edit]

As of the early 21st century, Yarmouth is mostly residential in character, with commercial development scattered throughout the town, particularly along Route 1 and Main Street (State Route 115).

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ MHPCPC at MaineStateMuseum.org

- ^ Architectural Survey Yarmouth, ME (Phase One, September, 2018 - Yarmouth's town website)

- ^ a b c d e Yarmouth Historical Society, via the Yarmouth/North Yarmouth Community Guide, Portland Press Herald, Summer 2007

- ^ "Ancient North Yarmouth and Yarmouth" Archived 2018-10-04 at the Wayback Machine - Yarmouth Historical Society

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Ancient North Yarmouth and Yarmouth, Maine 1636-1936: A History, William Hutchinson Rowe (1937)

- ^ a b "Muddy Waters", Portland Magazine (June 2020)

- ^ Westcustogo Inn

- ^ "Cousins Make Mark on Maine" - banfield-hodgkinsfamily.com

- ^ a b c Captain Walter Gendall, of North Yarmouth, Maine: A Biographical Sketch, Doctor Charles E. Banks (1880) - HathiTrust

- ^ History of Cumberland County, Maine: Town of Cumberland, Everts & Peck, 1880

- ^ North Yarmouth Necrology, 1736–1762 - Rev. Amasa Loring

- ^ "Maine Ulster Scots Project" - Facebook, May 6, 2016

- ^ a b Maine's Historic Places, Frank Beard (1982)

- ^ Yarmouth Historical Society: The National Register of Historic Places

- ^ Cemetery Records at YarmouthMEHistory.org

- ^ Images of America: Yarmouth, Alan M. Hall (Arcadia, 2002), p.6

- ^ a b c Yarmouth Revisited, Amy Aldredge

- ^ a b c Images of America: Yarmouth, Hall, Alan M., Arcadia (2002)

- ^ Images of America: Yarmouth, Alan M. Hall (Arcadia, 2002), p.11

- ^ "Grippe Quarantines Maine Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 2023-03-27.

- ^ Images of America: Yarmouth, Alan M. Hall (Arcadia, 2002), p.23

- ^ "Edna May Morrill Obituary" - Legacy.com, August 22, 2007