Holy Sonnets

The Holy Sonnets—also known as the Divine Meditations or Divine Sonnets—are a series of nineteen poems by the English poet John Donne (1572–1631). The sonnets were first published in 1633—two years after Donne's death. They are written predominantly in the style and form prescribed by Renaissance Italian poet Petrarch (or Francesco Petrarca) (1304–1374) in which the sonnet consisted of two quatrains (four-line stanzas) and a sestet (a six-line stanza). However, several rhythmic and structural patterns as well as the inclusion of couplets are elements influenced by the sonnet form developed by English poet and playwright William Shakespeare (1564–1616).

Donne's work, both in love poetry and religious poetry, places him as a central figure among the Metaphysical poets. The nineteen poems that constitute the collection were never published during Donne's lifetime although they did circulate in manuscript. Many of the poems are believed to have been written in 1609 and 1610, during a period of great personal distress and strife for Donne who suffered a combination of physical, emotional and financial hardships during this time. This was also a time of personal religious turmoil as Donne was in the process of conversion from Roman Catholicism to Anglicanism, and would take holy orders in 1615 despite profound reluctance and significant self-doubt about becoming a priest.[1] Sonnet XVII ("Since she whom I loved hath paid her last debt") is thought to have been written in 1617 following the death of his wife Anne More.[1] In Holy Sonnets, Donne addresses religious themes of mortality, divine judgment, divine love and humble penance while reflecting deeply personal anxieties.[2]

Composition and publication[edit]

Writing[edit]

The dating of the poems' composition has been tied to the dating of Donne's conversion to Anglicanism. His first biographer, Izaak Walton, claimed the poems dated from the time of Donne's ministry (he became a priest in 1615); modern scholarship agrees that the poems date from 1609 to 1610, the same period during which he wrote an anti-Catholic polemic, Pseudo-Martyr.[3]: p.385 "Since she whom I loved, hath paid her last debt," though, is an elegy to Donne's wife, Anne, who died in 1617,[4]: p.63 and two other poems, "Show me, dear Christ, thy spouse so bright and clear" and "Oh, to vex me, contraries meet as one" are first found in 1620.[4]: p.51

Publication history[edit]

The Holy Sonnets were not published during Donne's lifetime. It is thought that Donne circulated these poems amongst friends in manuscript form. For instance, the sonnet "Oh my black soul" survives in no fewer than fifteen manuscript copies, including a miscellany compiled for William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The sonnets, and other poems, were first published in 1633—two years after his death.

Among the nineteen poems that are grouped together as the Holy Sonnets, there is variation among manuscripts and early printings of the work. Poems are listed in different order, some poems are omitted. In his Variorum edition of Donne's poetry, Gary A. Stringer proposed that there were three sequences for the sonnets.[5]: pp.ix–x, 5–27 Only eight of the sonnets appear in all three versions.[4]: p.51

- The first sequence (which Stringer calls the "original sequence") contained twelve poems. This sequence survives in manuscripts only (British Library MS Stowe 961, Harvard University Library MS Eng 966.4 and Henry E. Huntington Library Bridgewater MS).[5]: pp.lx-lxiii

- The second sequence (called the "Westmoreland sequence") contained nineteen poems. This sequence was prepared circa 1620 by Rowland Woodward, a friend of Donne who was serving as the secretary to Sir Francis Fane (1580–1629) who in 1624 became the first Earl of Westmorland. The Westmoreland manuscript is in the collection of the New York Public Library in Manhattan.

- The third sequence (which Stringer calls the "revised sequence") contained twelve poems—eight sonnets from the original sequence (in a different order) and four sonnets from the Westmoreland manuscript. This sequence was the basis for the 1633 print edition of Donne's poems.[5]: pp.lx-lxiii John T. Shawcross has remarked the importance of establishing the order(s), saying that "[a]nyone who has paid attention to Donne's Holy Sonnets is aware that the order in which the sonnets appear casts 'meanings' upon them." Quoted from "A Text of John Donne's Poems: Unsatisfactory Compromise," John Donne Journal 2 (1983), 11. The editors of the Variorum have remarked Donne's "ordering of the sonnets [as]...a matter of continuing authorial attention," LXI. A first response to the Variorum editors is Roberta J. Albrecht, who establishes the clock motif as ordering principle for the 1633 sequence of twelve sonnets. Albrecht, Using Alchemical Memory Techniques for the Interpretation of Literature: John Donne, George Herbert, and Richard Crashaw, The Edwin Mellen Press Ltd. Lampeter, Caredigion, Wales (2008). See chapter I, pp. 39–96.

The 1635 edition of Donne's poems again included the four sonnets that were present in the original sequence but dropped in the revised one, making it a total of sixteen poems, and this became the standard until the late nineteenth century.[5]: p.lxiii Most modern editions of the sonnets adopt the order established in 1912 by Herbert Grierson, who incorporated MS Westmoreland sonnets 17, 18 and 19 into the 1635 sequence and thus produced a list of 19 poems—like the Westmoreland manuscript, but in a different order.[5]: pp.lx, lxxvi

| First line | Composition date[6] | "Original sequence" (BL MS Stowe 961) | Westmoreland MS (1620) | Poems (1633) | Grierson (1912) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thou hast made me, and shall thy work decay | c. 1609–1611 | 01 | 01 | omitted | 01 |

| As due by many titles I resign | unknown | 02 | 02 | 01 | 02 |

| O might those sighs and tears return again | c. 1609–1611 | 03 | 03 | omitted | 03 |

| Father, part of his double interest | 04 | 04 | 12 | 16 | |

| O, my black soul, now thou art summoned | Feb.-Aug. 1609 | 05 | 05 | 02 | 04 |

| This is my play's last scene, here heavens appoint | 06 | 06 | 03 | 06 | |

| I am a little world made cunningly | 07 | 07 | omitted | 05 | |

| At the round earth's imagined corners, blow | Feb.-Aug. 1609 | 08 | 08 | 04 | 07 |

| If poisonous minerals, and if that tree | 09 | 09 | 05 | 09 | |

| If faithful souls be alike glorified | 10 | 10 | omitted | 08 | |

| Death be not proud, though some have called thee | Feb.-Aug. 1609 | 11 | 11 | 06 | 10 |

| Wilt thou love God, as he thee! then digest | 12 | 12 | 11 | 15 | |

| Spit in my face you Jews, and pierce my side | omitted | 13 | 07 | 11 | |

| Why are we by all creatures waited on? | omitted | 14 | 08 | 12 | |

| What if this present were the world's last night? | c. 1609 | omitted | 15 | 09 | 13 |

| Batter my heart, three-personed God; for you | c. 1609 | omitted | 16 | 10 | 14 |

| Since she whom I loved hath paid her last debt | after August 1617 | omitted | 17 | omitted | 17 |

| Show me, dear Christ, thy spouse so bright and clear | omitted | 18 | omitted | 18 | |

| O, to vex me, contraries meet in one | after Jan. 1615 | omitted | 19 | omitted | 19 |

Analysis and interpretation[edit]

Themes[edit]

According to scholar A. J. Smith, the Holy Sonnets "make a universal drama of religious life, in which every moment may confront us with the final annulment of time."[1] The poems address "the problem of faith in a tortured world with its death and misery."[8] Donne's poetry is heavily informed by his Anglican faith and often provides evidence of his own internal struggles as he considers pursuing the priesthood.[1] The poems explore the wages of sin and death, the doctrine of redemption, opening "the sinner to God, imploring God's forceful intervention by the sinner's willing acknowledgment of the need for a drastic onslaught upon his present hardened state" and that "self-recognition is a necessary means to grace."[1] The personal nature of the poems "reflect their author's struggles to come to terms with his own history of sinfulness, his inconstant and unreliable faith, his anxiety about his salvation."[9]: p.108 He is obsessed with his own mortality but acknowledges it as a path to God's grace.[10] Donne is concerned about the future state of his soul, fearing not the quick sting of death but the need to achieve salvation before damnation and a desire to get one's spiritual affairs in order. The poems are "suffused with the language of bodily decay" expressing a fear of death that recognizes the impermanence of life by descriptions of his physical condition and inevitability of "mortal flesh" compared with an eternal afterlife.[9]: p.106–107

It is said that Donne's sonnets were heavily influenced by his connections to the Jesuits through his uncle Jasper Heywood, and from the works of the founder of the Jesuit Order, Ignatius Loyola.[9]: p.109 [11] Donne chose the sonnet because the form can be divided into three parts (two quatrains, one sestet) similar to the form of meditation or spiritual exercise described by Loyola in which (1) the penitent conjures up the scene of meditation before him (2) the penitent analyses, seeking to glean and then embrace whatever truths it may contain; and (3) after analysis, the penitent is ready to address God in a form of petition or resign himself to divine will that the meditation reveals.[9]: p.109 [11][12]

Legacy[edit]

Musical settings[edit]

Several British composers have set Donne's sonnets to music. Hubert Parry included one of the sonnets, "At the round earth's imagined corners", in his collection of six choral motets, Songs of Farewell.[13] The pieces were first performed at a concert at the Royal College of Music on 22 May 1916, and a review in The Times stated that the setting of Donne's sonnet was "one of the most impressive short choral works written in recent years".[14]

Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) set nine of the sonnets for soprano or tenor and piano in his song cycle The Holy Sonnets of John Donne, Op. 35 (1945).[15] Britten wrote the songs in August 1945 for tenor Peter Pears, his lover and a musical collaborator since 1934.[8] Britten had been "encouraged...to explore the work of Donne" by poet W. H. Auden.[8][16] However, Britten was inspired to compose the work after visiting concentration camps in Germany after World War II ended as part of a concert tour for Holocaust survivors organised by violinist Yehudi Menuhin. Britten was shocked by the experience and Pears later asserted that the horrors of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp were an influence on the composition.[17]

Britten set the following nine sonnets:

- 1. Oh my blacke soule!

- 2. Batter my heart

- 3. O might those sighes and teares

- 4. Oh, to vex me

- 5. What if this present

- 6. Since she whom I loved

- 7. At the round earth's imagined corners

- 8. Thou hast made me

- 9. Death, be not proud

According to Britten biographer Imogen Holst, Britten's ordering of Donne's sonnets indicates that he "would never have set a cruel subject to music without linking the cruelty to the hope of redemption."[18] Britten's placement of the sonnets are first those whose themes explore conscience, unworthiness and death (Songs 1–5), to the personal melancholy of the sixth song ("Since she whom I loved") written by Donne after the death of his wife, and the last three songs (7–9) the idea of resurrection.[8]

John Tavener (born 1944), known for his religious and minimalist music, set three of Donne's sonnets ("I Spit in my face," "Death be not proud," and "I am a little world made cunningly") for soloists and a small ensemble of two horns, trombone, bass trombone, timpani and strings in 1962. The third in the series he wrote as a schoolboy, and the first two settings were inspired by the death of his maternal grandmother.[19]

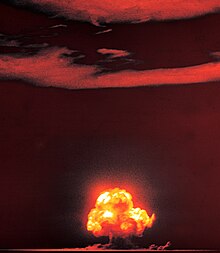

Sonnet XIV and the Trinity site[edit]

It is thought that theoretical physicist and Manhattan Project director J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967), regarded as the "father of the Atomic Bomb", named the site of the first nuclear weapon test site "Trinity" after a phrase from Donne's Sonnet XIV. At the time of the preparations for the test on 16 July 1945 Oppenheimer reportedly was reading Holy Sonnets. In 1962, Lieutenant General Leslie Groves (1896–1970) wrote to Oppenheimer about the origin of the name, asking if he had chosen it because it was a name common to rivers and peaks in the West and would not attract attention.[20] Oppenheimer replied:

I did suggest it, but not on that ground... Why I chose the name is not clear, but I know what thoughts were in my mind. There is a poem of John Donne, written just before his death, which I know and love. From it a quotation: "As West and East / In all flatt Maps—and I am one—are one, / So death doth touch the Resurrection." That still does not make a Trinity, but in another, better known devotional poem Donne opens, "Batter my heart, three-person'd God;—."[20][21]

Historian Gregg Herken believes that Oppenheimer named the site in reference to Donne's poetry as a tribute to his deceased mistress, psychiatrist and physician Jean Tatlock (1914–1944)—the daughter of an English literature professor and philologist—who introduced Oppenheimer to the works of Donne.[22]: pp.29, 129 Tatlock, who suffered from severe depression, committed suicide in January 1944 after the conclusion of her affair with Oppenheimer.[22]: p.119 [23]

The history of the Trinity test, and the stress and anxiety of the Manhattan Project's workers in the preparations for the test was the focus of the 2005 opera Doctor Atomic by contemporary American composer John Adams, with libretto by Peter Sellars. At the end of Act I, the character of Oppenheimer sings an aria whose text is derived from Sonnet XIV ("Batter my heart, three-person'd God;—").[24][25]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Smith, A. J. Biography: John Donne 1572–1631 at Poetry Foundation (www.poetryfoundation.org). Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ Ruf, Frederick J. Entangled Voices: Genre and the Religious Construction of the Self. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 41. ISBN 978-0-19-510263-5.

- ^ Cummings, Brian. The Literary Culture of the Reformation: Grammar and Grace. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). ISBN 978-0-19-922633-7

- ^ a b c Cummings, Robert M. Seventeenth-Century Poetry: An Annotated Anthology. (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000). ISBN 978-0-631-21066-5

- ^ a b c d e Stringer, Gary A. The Variorum Edition of the Poetry of John Donne. Volume 7, Part 1. (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2005). ISBN 978-0-253-34701-5

- ^ Dates from Donne, John, and Shawcross, John (editor). The Complete Poetry of John Donne. (New York: New York UP; London: U of London P, 1968).

- ^ Lapham, Lewis. The End of the World. (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 1997), 98.

- ^ a b c d Gooch, Bryan N.S. "Britten and Donne: Holy Sonnets Set to Music" in Early Modern Literary Studies Special Issue 7 (May 2001), 13:1–16.

- ^ a b c d Targoff, Ramie. John Donne, Body and Soul. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008). ISBN 978-0-226-78963-7

- ^ Ettari, Gary. "Rebirth and Renewal in John Donne's The Holy Sonnets," in Bloom, Harold, and Hobby, Blake (editors). Bloom's Literary Themes: Rebirth and Renewal (New York: Infobase Publishing, 2009), 125. ISBN 978-0-7910-9805-9

- ^ a b Martz, Louis L. The Poetry of Meditation: A Study in English Religious Literature of the 17th Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 107–112, 221–235; and "John Donne in Meditation: The Anniversaries," English Literary History 14(4) (December 1947), 248–62.

- ^ Capps, Donald. "A Spiritual Person," in Cole, Allan Hugh Jr. (editor). A Spiritual Life: Perspectives from Poets, Prophets, and Preachers (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 96. ISBN 978-0-664-23492-8

- ^ Shrock, Dennis (2009). Choral Repertoire. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780195327786. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Keen, Basil (2017). The Bach Choir: The First Hundred Years. Routledge. pp. 96–7. ISBN 9781351546072. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Evans, Peter. The Music of Benjamin Britten. (2nd Ed. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 349–353. ISBN 978-0-19-816590-3; White, Eric Walter. Benjamin Britten: His Life and Operas. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970), 45. ISBN 978-0-520-01679-8

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey. Benjamin Britten: A Biography. (London: Faber & Faber, 1992), 227.

- ^ Pears, Peter. "The Vocal Music" in Mitchell, Donald and Keller, Hans (editors) Benjamin Britten: A Commentary on His Works from a Group of Specialists. (London: Rockliff Publishing, 1952; rprt. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1972), 69–70.

- ^ Holst, Imogen. Britten. The Great Composers. (3rd ed.-London and Boston: Faber & Faber, 1980), 40.

- ^ Stewart, Andrew. John Tavener : Three Holy Sonnets – Programme Note. G. Schrimer Inc. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ a b Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986), 571–572.

- ^ Oppenheimer references quotations from two of Donne's poems, the first from Donne's "Hymne to God My God, in My Sicknesse", and the second "Sonnet XIV" from Holy Sonnets—both of which can be found in Donne, John, and Chambers E. K. (editor). Poems of John Donne]. Volume I. (London: Lawrence & Bullen, 1896), 165, 211–212.

- ^ a b Herken, Gregg. Brotherhood of the Bomb. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2003). ISBN 978-0-8050-6589-3

- ^ Bird, Kai, and Martin J. Sherwin. American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 249–254. ISBN 978-0-375-41202-8

- ^ Ross, Alex, "Onwards and upward with the arts: Countdown: John Adams and Peter Sellars create an atomic opera", The New Yorker (3 October 2005), 60–71.

- ^ Peter Sellars, Libretto for "Doctor Atomic." (London: Boosey and Hawkes, 2004), Act I.

External links[edit]

Holy Sonnets public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Holy Sonnets public domain audiobook at LibriVox

•"Preaching on the Holy Sonnets"—article by Jeff Dailey http://www.pulpit.org/2018/06/preaching-on-the-holy-sonnets/