Homologous chromosome: Difference between revisions

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

There are severe repercussions when chromosomes do not segregate properly. Faulty segregation can lead to [[infertility|fertility]] problems, [[Embryo#Miscarriage|embryo death]], [[Congenital disorder|birth defects]], and [[cancer]].<ref name=" Gerton">{{cite journal | author = Gerton JL, Hawley RS | title = Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: diversity amidst conservation | journal = Nat. Rev. Genet. | volume = 6 | issue = 6 | pages = 477–87 |date=June 2005 | pmid = 15931171 | doi = 10.1038/nrg1614 }}</ref> Though the mechanisms for pairing and adhering homologous chromosomes vary among organisms, proper functioning of those mechanisms is imperative in order for the final [[Genomes|genetic material]] to be sorted correctly.<ref name=" Gerton"/> |

There are severe repercussions when chromosomes do not segregate properly. Faulty segregation can lead to [[infertility|fertility]] problems, [[Embryo#Miscarriage|embryo death]], [[Congenital disorder|birth defects]], and [[cancer]].<ref name=" Gerton">{{cite journal | author = Gerton JL, Hawley RS | title = Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: diversity amidst conservation | journal = Nat. Rev. Genet. | volume = 6 | issue = 6 | pages = 477–87 |date=June 2005 | pmid = 15931171 | doi = 10.1038/nrg1614 }}</ref> Though the mechanisms for pairing and adhering homologous chromosomes vary among organisms, proper functioning of those mechanisms is imperative in order for the final [[Genomes|genetic material]] to be sorted correctly.<ref name=" Gerton"/> |

||

Proper functioning of this homologous pairing is a key process whereby species are genetically separated and maintained during evolution; and natural selection for regular homologous behavior of chromosomes may be particularly significant in the formation of species in macro-evolution. Without internal mechanisms for reproductive separation, general phenotypic adaptation of attributes is hard-pressed to account for speciation. <ref name= " Stebbins"/> Fortunately, we do have an example of the importance of chromosome homology in the establishment of species. The evolution of bread wheat (''Triticum aestivum'') has reached the stage where there are three sub-genomes of chromosomes within the overall genome. Usually, meiosis behaves regularly, with strictly homologous pairing of the chromosomes within their respective sub-genome. However, while attempting inter-species crosses, wheat breeders discovered the presence of a controlling allele (in one gene on the D sub-genome) which enforces this strict homology. In the presence of the alternative allele (which does exist naturally, by the way, in the centre of origin of wheat) partial chromosome pairing occurs amongst "homœologues" (quasi-homologues)across the sub-genomes, as well as strict homology within sub-genomes. The result is chromosome entanglements during anaphase of meiosis (partial non-disjunction), and significant drop in fertility. In the presence of the controlling allele, however, regular strictly-homologous chromosome pairing is enforced, and regular meiosis resumes, along with normal fertility. This is one of the few clear examples we have of such incipient speciation in action: and therefore it is of great importance to know of it. It is very obvious that natural selection for such alleles would be very strong, as loss of fertility is a major cause of "failure" in evolution. There are many, many examples of chromosome incompatibilities underlying species separation: this wheat example is one of the few "part-way" examples we have. <ref>Stebbins G.L. (1950) "Variation and Evolution in Plants"</ref> |

|||

===Nondisjunction=== |

===Nondisjunction=== |

||

Proper homologous chromosome separation in meiosis I is crucial for sister chromatid separation in meiosis II.<ref name=" Gerton"/> A failure to separate properly is known as nondisjunction. There are two main types of nondisjunction that occur: [[trisomy]] and [[monosomy]]. Trisomy is caused by the presence of one additional chromosomes in the zygote as compared to the normal number, and monosomy is characterized by the presence of a one less chromosome in the zygote as compared to the normal number. If this uneven division occurs in meiosis I, then none of the daughter cells will have proper chromosomal distribution and severe effects can ensue, including Down’s syndrome.<ref name="urlChromosomal Inheritance">{{cite web | url = http://www.uic.edu/classes/bms/bms655/lesson9.html | title = Chromosomal Inheritance | author = Tissot, Robert and Kaufman, Elliot | work = Human Genetics | publisher = University of Illinois at Chicago }}</ref> Unequal division can also occur during the second meiotic division. Nondisjunction which occurs at this stage can result in normal daughter cells and deformed cells.<ref name=" Klug"/> |

Proper homologous chromosome separation in meiosis I is crucial for sister chromatid separation in meiosis II.<ref name=" Gerton"/> A failure to separate properly is known as nondisjunction. There are two main types of nondisjunction that occur: [[trisomy]] and [[monosomy]]. Trisomy is caused by the presence of one additional chromosomes in the zygote as compared to the normal number, and monosomy is characterized by the presence of a one less chromosome in the zygote as compared to the normal number. If this uneven division occurs in meiosis I, then none of the daughter cells will have proper chromosomal distribution and severe effects can ensue, including Down’s syndrome.<ref name="urlChromosomal Inheritance">{{cite web | url = http://www.uic.edu/classes/bms/bms655/lesson9.html | title = Chromosomal Inheritance | author = Tissot, Robert and Kaufman, Elliot | work = Human Genetics | publisher = University of Illinois at Chicago }}</ref> Unequal division can also occur during the second meiotic division. Nondisjunction which occurs at this stage can result in normal daughter cells and deformed cells.<ref name=" Klug"/> |

||

Revision as of 07:22, 30 June 2014

A homologous chromosome is a set of one maternal chromosome and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during meiosis. These copies have the same genes in the same locations, or loci. These loci provide points along each chromosome which enable a pair of chromosomes to align correctly with each other before separating during meiosis.[1] Genetic recombination occurs during meiosis in cells containing these parental chromosomes, producing genotypes in the offspring that are new and different combinations of the parental alleles.[2] This recombination is due to either pairs of homologous chromosomes randomly segregating into two different daughter cells, or by crossing over, a process where homologous chromosomes exchange lengths of their genetic material.[3] This is the basis for Gregor Mendel’s laws of genetics that characterize inheritance patterns of genetic material from an organism to its offspring.[2]

Overview

Chromosomes are linear arrangements of condensed deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and histone proteins, which forms a complex called chromatin.[2] Homologous chromosomes are made up of chromosome pairs of approximately the same length, centromere position, and staining pattern, for genes with the same corresponding loci. One homologous chromosome is inherited from the organism's mother; the other is inherited from the organism's father. After mitosis occurs within the daughter cells, they have the correct number of genes which are a mix of the two parents' genes. In diploid (2n) organisms, the genome is composed of one set of each homologous chromosome pair, as compared to tetraploid organisms which may have two sets of each homologous chromosome pair. The alleles on the homologous chromosomes may be different, resulting in different phenotypes of the same genes. This mixing of maternal and paternal traits is enhanced by crossing over during meiosis, wherein lengths of chromosomal arms and the DNA they contain within a homologous chromosome pair are exchanged with one another.[4]

History

Early in the 1900s William Bateson and Reginald Punnett were studying genetic inheritance and they noted that some combinations of alleles appeared more frequently than others. That data and information was further explored by Thomas Morgan. Using test cross experiments, he revealed that, for a single parent, the alleles of genes near to one another along the length of the chromosome move together. Using this logic he concluded that the two genes he was studying were located on homologous chromosomes. Later on during the 1930s Harriet Creighton and Barbara McClintock were studying meiosis in corn cells and examining gene loci on corn chromosomes.[2] Creighton and McClintock discovered that the new allele combinations present in the offspring and the event of crossing over were directly related.[2] This proved intrachromosomal genetic recombination.[2]

Structure

Homologous chromosomes are chromosomes which contain the same genes in the same order along their chromosomal arms. There are two main properties of homologous chromosomes: the length of chromosomal arms and the placement of the centromere [5]

The actual length of the arm, in accordance with the gene locations, is critically important for proper alignment. Centromere placement can be characterized by four main arrangements, consisting of being either metacentric, submetacentric, telocentric, or acrocentric. Both of these properties are the main factors for creating structural homology between chromosomes. Therefore when two chromosomes of the exact structure exist, they are able to pair together to form homologous chromosomes.[5]

Since homologous chromosomes are not identical and do not originate from the same organism, they are different from sister chromatids. Sister chromatids result after DNA replication has occurred, and thus are identical, side-by-side duplicates of each other.[3]

In humans

Humans have a total of 46 chromosomes, but there are only 22 pairs of homologous autosomal chromosomes. The additional 23rd pair is the sex chromosomes, X and Y. If this pair is made up of an X and Y chromosome, then the pair is not truly homologous because their size and types of genes differ slightly. The 22 pairs of homologous chromosomes contain the same genes but code for different traits in their allelic forms since one was inherited from the mother and one from the father.[6] So humans have two homologous chromosome sets in each cells, meaning humans are diploid organisms.[2]

Functions

Homologous chromosomes are important in the processes of meiosis and mitosis. They allow for the recombination and random segregation of genetic material from the mother and father into new cells.[7]

In meiosis

Meiosis is a round of two cell divisions that results in four haploid daughter cells that each contain half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell.[8] It reduces the chromosome number in a germ cell by half by first separating the homologous chromosomes in meiosis I and then the sister chromatids in meiosis II. The process of meiosis I is generally longer than meiosis II because it takes more time for the chromatin to replicate and for the homologous chromosomes to be properly oriented and segregated by the processes of pairing and synapsis in meiosis I.[3] The implications of genetic recombination by random segregation and crossing over during meiosis, are that the daughter cells all contain different combinations of maternally and paternally coded genes.[8] This recombination of genes allows for the introduction of new allele pairings and genetic variation.[2] Genetic variation among organisms helps make a population more stable by providing a wider range of genetic traits for natural selection to act on.[2]

Prophase I

In prophase I of meiosis I, each chromosome is aligned with its homologous partner and pairs completely. In prophase I, the DNA has already undergone replication so each chromosome consists of two identical chromatids connected by a common centromere.[8] During the zygotene stage of prophase I, the homologous chromosomes pair up with each other.[8] This pairing occurs by a synapsis process where the synaptonemal complex - a protein scaffold - is assembled and joins the homologous chromosomes along their lengths.[3] Cohesin crosslinking occurs between the homologous chromosomes and helps them resist being pulled apart until anaphase.[6] Genetic crossing over occurs during the pachytene stage of prophase I.[8] In this process, genes are exchanged by the breaking and union of homologous portions of the chromosomes’ lengths.[3] Structures called chiasmata are the site of the exchange. Chiasmata physically link the homologous chromosomes once crossing over occurs and throughout the process of chromosomal segregation during meiosis.[3] At the diplotene stage of prophase I the synaptonemal complex disassembles before which will allow the homologous chromosomes to separate, while the sister chromatids stay associated by their centromeres.[3]

Metaphase I

In metaphase I of meiosis I, the pairs of homologous chromosomes, also known as bivalents or tetrads, line up in a random order along the metaphase plate.[8] The random orientation is another way for cells to introduce genetic variation. Meiotic spindles emanating from opposite spindle poles attach to each of the homologs (each pair of sister chromatids) at the kinetochore.[6]

Anaphase I

In anaphase I of meiosis I the homologous chromosomes are pulled apart from each other. The homologs are cleaved by the enzyme separase to release the cohesin that held the homologous chromosome arms together.[6] This allows the chiasmata to release and the homologs to move to opposite poles of the cell.[6] The homologous chromosomes are now randomly segregated into two daughter cells that will undergo meiosis II to produce four haploid daughter germ cells.[2]

Meiosis II

After the tetrads of homologous chromosomes are separated in meiosis I, the sister chromatids from each pair are separated. The two diploid daughter cells resulting from meiosis I undergo another cell division in meiosis II but without another round of chromosomal replication. The sister chromatids in the two daughter cells are pulled apart during anaphase II by nuclear spindle fibers, resulting in four haploid daughter cells.[2]

In mitosis

Homologous chromosomes do not function the same in mitosis as they do in meiosis. Prior to every single mitotic division a cell undergoes, the chromosomes in the parent cell replicate themselves. The homologous chromosomes within the cell will not pair up and undergo genetic recombination with each other.[8] Instead, the replicants, or sister chromatids, will line up along the metaphase plate and then separate in the same way as meiosis II - by being pulled apart at their centromeres by nuclear mitotic spindles.[9] If any crossing over does occur between sister chromatids during mitosis, it does not produce any recombinants.[2]

Problems

There are severe repercussions when chromosomes do not segregate properly. Faulty segregation can lead to fertility problems, embryo death, birth defects, and cancer.[10] Though the mechanisms for pairing and adhering homologous chromosomes vary among organisms, proper functioning of those mechanisms is imperative in order for the final genetic material to be sorted correctly.[10]

Nondisjunction

Proper homologous chromosome separation in meiosis I is crucial for sister chromatid separation in meiosis II.[10] A failure to separate properly is known as nondisjunction. There are two main types of nondisjunction that occur: trisomy and monosomy. Trisomy is caused by the presence of one additional chromosomes in the zygote as compared to the normal number, and monosomy is characterized by the presence of a one less chromosome in the zygote as compared to the normal number. If this uneven division occurs in meiosis I, then none of the daughter cells will have proper chromosomal distribution and severe effects can ensue, including Down’s syndrome.[11] Unequal division can also occur during the second meiotic division. Nondisjunction which occurs at this stage can result in normal daughter cells and deformed cells.[5]

Embryonic death

If unequal genetic crossover occurs within the gametes involved in meiosis, then the resulting zygote may suffer unviability.[5] This is caused by events such as trisomy and monosomy because the cells are not able to develop normally with these characteristics. In other terms, one cell gains the proper amount of genetic material while the other cell lacks that material.[11] Consequently, these deformed cells may cause a spontaneous abortion because the zygote does not develop correctly.[11]

Other uses

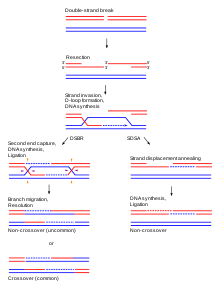

While the main function of homologous chromosomes is their use in nuclear division, they are also used in repairing double-strand breaks of DNA.[12] These double-stranded breaks typically occur in DNA that serve as template strands for DNA replication, and they are the result of mutation, replication errors or malfunctioning DNA.[13] Homologous chromosomes can repair this damage by aligning themselves with chromosomes of the same genetic sequence.[12] Once the base pairs have been matched and oriented correctly between the two strands, the homologous chromosomes perform a process that is very similar to recombination, or crossing over as seen in meiosis. Part of the intact DNA sequence overlaps with that of the damaged chromosome's sequence. Replication proteins and complexes are then recruited to the site of damage, allowing for repair and proper replication to occur.[13] Through this functioning, double-strand breaks can be repaired and DNA can function normally.[12]

Relevant research

Current and future research on the subject of homologous chromosome is heavily focused on the roles of various proteins during recombination or during DNA repair. In a recently published article by Pezza et al. the protein known as HOP2 is responsible for both homologous chromosome synapsis as well as double-strand break repair via homologous recombination. The deletion of HOP2 in mice has large repercussions in meiosis.[14] Other current studies focus on specific proteins involved in homologous recombination as well.

There is ongoing research concerning the ability of homologous chromosomes to repair double-strand DNA breaks. Researchers are investigating the possibility of exploiting this capability for regenerative medicine.[15] This medicine could be very prevalent in relation to cancer, as DNA damage is thought to be contributor to carcinogenesis. Manipulating the repair function of homologous chromosomes might allow for bettering a cell’s damage response system. While research has not yet confirmed the effectiveness of such treatment, it may become a useful therapy for cancer.[16]

See also

- Homologous recombination

- Mendelian inheritance

- Developmental biology

- Synapsis

- Non-disjunction

- Heredity

References

- ^ "Homologous chromosomes". Genetics Home Reference - Glossary Entry. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Griffiths JF, Gelbart WM, Lewontin RC, Wessler SR, Suzuki DT, Miller JH (2005). Introduction to Genetic Analysis. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co. pp. 34–40, 473–476, 626–629. ISBN 0-7167-4939-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Pollard TD, Earnshaw WC, Lippincott-Schwartz J (2008). Cell Biology (2 ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 815, 821–822. ISBN 1-4160-2255-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Campbell NA, Reece JB (2002). Biology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-6624-5.

- ^ a b c d Klug, William S. (2012). Concepts of Genetics. Boston: Pearson. pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c d e Lodish HF (2013). Molecular cell biolog. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co. pp. 355, 891. ISBN 1-4292-3413-X.

- ^ Gregory MJ. "The Biology Web". Clinton Community College – State University of New York.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gilbert SF (2014). Developmental Biology. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. pp. 606–610. ISBN 978-0-87893-978-7.

- ^ "The Cell Cycle & Mitosis Tutorial". The Biology Project. University of Arizona. Oct 2004.

- ^ a b c Gerton JL, Hawley RS (June 2005). "Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: diversity amidst conservation". Nat. Rev. Genet. 6 (6): 477–87. doi:10.1038/nrg1614. PMID 15931171.

- ^ a b c Tissot, Robert and Kaufman, Elliot. "Chromosomal Inheritance". Human Genetics. University of Illinois at Chicago.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Sargent RG, Brenneman MA, Wilson JH (January 1997). "Repair of site-specific double-strand breaks in a mammalian chromosome by homologous and illegitimate recombination" (PDF). Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (1): 267–77. PMC 231751. PMID 8972207.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kuzminov A (July 2001). "DNA replication meets genetic exchange: chromosomal damage and its repair by homologous recombination". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (15): 8461–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.151260698. PMC 37458. PMID 11459990.

- ^ Petukhova GV, Romanienko PJ, Camerini-Otero RD. The Hop2 protein has a direct role in promoting interhomolog interactions during mouse meiosis. Dev Cell. 2003 Dec;5(6):927-36. PubMed PMID 14667414.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23478019, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23478019instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11242102, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11242102instead.

Further reading

- Gilbert SF (2003). Developmental biolog. Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-258-5.

- OpenStaxCollege (25 Apr 2013). "Meiosis". Rice University.