Hurufiyya movement

The Hurufiyya movement (Template:Lang-ar hurufiyya, adjective form hurufi literal meaning "letters" [of the alphabet]) was an aesthetic movement that emerged in the late twentieth century amongst Arabian and North African artists, who used their understanding of traditional Islamic calligraphy, within the precepts of modern art. By combining tradition and modernity, these artists worked towards developing a Pan-Arab visual language, which instilled a sense of national identity in their respective nation states, at a time when many of these states where shaking off colonial rule and asserting their independence. They adopted the same name as the Hurufi, an approach of Sufism which emerged in the late 14th–early 15th century. Art historian, Dagher, has described hurufiyya as the most important movement to emerge in the Arab art world in the 20th-century.

Definition

The term, hurifiyya is derived from the Arabic term, harf which means letter (as in a letter of the alphabet). When the term is used to describe an contemporary art movement, it explicitly references a Medieval system of teaching involving political theology and lettrism. In this theology, letters were seen as primordial signifiers and manipulators of the cosmos.[1] Thus, the term is charged with Sufi intellectual and esoteric meaning. [2]

The hurufiyya art movement (also known as the Al-hurufiyyah movement[3] or the Letrism movement[4]) refers to the use of calligraphy as a graphic element within an artwork, typically an abstract work.[5] The pan-Arab hurufiyya art movement is distinct from the Letterist International which had an Algerian section founded in Chlef in 1953 by Hadj Mohamed Dahou.

The term, hurufiyya has become somewhat controversial and has been rejected by a number of scholars, including Wijdan Ali, Nada Shabout and Karen Dabrowska. An alternative term, al-Madrassa al-Khattiya Fil-Fann [Calligraphic School of Art] has been proposed to describe the experimental use of calligraphy in modern Arabic art.[6]

Brief history and philosophy

Traditional hurufi art was bound by strict rules, which amongst other things, confined calligraphy to devotional works and prohibited the representation of humans in manuscripts.[7] Practising calligraphers trained with a master for many years in order to learn both the technique and the rules governing calligraphy. Contemporary hurufiyya artists broke free from these rules, allowing Arabic letters to be deconstructed, altered and included in abstract artworks.[8]

The use of traditional Arabic elements, notably, calligraphy, in modern art arose independently in various Islamic states; few of these artists working in this area, had knowledge of each other, allowing for different manifestations of hurufiyya to develop in different regions. [9] In Sudan, for instance, the movement was known as the Old Khartoum School,[10] and assumed a distinctive character in which both African motifs and calligraphy were combined, while media such as leather and wood replaced canvas to provide a distinct African style.[11] In Morocco, the movement was accompanied by the replacement of traditional media for oils; artists favoured traditional dyes such as henna, and embraced weaving, jewellery and tattoo as well as including traditional Berber motifs.[12] In Jordan, it was generally known as the al-hurufiyyah movement, while in Iran, the Saqqa-Khaneh movement.[13]

Some scholars have suggested that Madiha Omar, who was active in the US and Baghdad from the mid-1940s, was the pioneer of the movement, since she was the first to explore the use of Arabic script in a contemporary art context in the 1940s and exhibited hurufiyya-inspired works in Washington in 1949.[14] However, other scholars have suggested that she was a precursor to Hurufiyya[15]. Yet other scholars have suggested that the hurufiyya art movement probably began in North Africa, in the area around Sudan, with the work of Ibrahim el-Salahi,[16] who initially explored Coptic manuscripts, a step that led him to experiment with Arabic calligraphy.[17] It is clear that by the early 1950s, a number of artists in different countries were experimenting with works based on calligraphy, including the Iraqi painter and sculptor, Jamil Hamoudi who experimented with the graphic possibilities of using Arabic characters, as early as 1947;[18] Iranian painters, Nasser Assar (b. 1928) (fr:Nasser Assar) and Hossein Zenderoudi, who won a prize at the 1958 Paris Biennale.[19]

Hurufiyya artists rejected Western art concepts, and instead grappled with a new artistic identity drawn from within their own culture and heritage. These artists successfully integrated Islamic visual traditions, especially calligraphy, into contemporary, indigenous compositions. [20] The common theme amongst hurufiyya artists is that they all tapped into the beauty and mysticism of Arabic calligraphy, but used it in a modern, abstract sense. [21] Although hurufiyya artists struggled to find their own individual dialogue with nationalism, they also worked towards a broader aesthetic that transcended national boundaries and represented an affiliation with an Arab identity in the post-colonial period.[22]

The art historian, Christiane Treichl, explains how calligraphy is used in contemporary art:[23]

- "They deconstruct writing, exploit the letter and turn it into an indexical sign of calligraphy, tradition and cultural heritage. As the sign is purely aesthetic, and only linguistic in its cultural association, it opens hitherto untravelled avenues for interpretation, and attracts different audiences, yet still maintains a link to the respective artist's own culture... Hurufiyya artists do away with the signifying function of language. The characters become pure signs, and temporarily emptied of their referential meaning, they become available for new meanings."

The hurufiyya art movement was not confined to painters, but also included important ceramicists such as the Jordanian, Mahmoud Taha, who combined traditional aesthetics, including calligraphy, with skilled craftsmanship,[24] and sculptors, such as the Qatari, Yousef Ahmad[25] and the Iraqi sculptors, Jawad Saleem and Mohammed Ghani Hikmat. Nor, was the movement organised along formal lines across the Arab-speaking nations. In some Arab nations, hurufiyya artists formed formal groups or societies, such as Iraq's Al Bu'd al Wahad (or the One Dimension Group)" which published a manifesto,[26] while in other nations artists working independently in the same city had no knowledge of each other.[27]

Art historian, Dagher, has described hurufiyya as the most important movement to emerge in the Arab world in the 20th-century. [28] However, the Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, while acknowledging its importance in terms of encouraging Arab nationalism, describes hurufiyya as neither "a movement nor a school." [29]

Evolution of hurufiyya

Art historians have identified three generations of hurufiyya artists: [30]

- First generation: The pioneers, who inspired by the independence of their nations, searched for a new aesthetic language that would allow them to express their nationalism. These artists rejected European techniques and media, turning to indigenous media and introducing Arabic calligraphy into their art. For this group of artists, Arabic letters are a central feature of the artwork. First generation artists include: the Jordanian artist, Princess Wijdan Ali, the Sudanese artist, Ibrahim el-Salahi; the Iraqi artists, Shakkir Hassan Al Sa'id, Jamil Hamoudi and Jawad Saleem; the Lebanese painter and poet, Etel Adnan and the Egyptian artist, Ramzi Moustafa (b. 1926).

- Second generation: Artists, most of whom live in exile, but reference their traditions, culture and language in their artworks. The artist, Dia Azzawi is typical of this generation.

- Third generation: Contemporary artists who have absorbed international aesthetics, and who employ Arabic and Persian script occasionally. They deconstruct the letters, and use them in a purely abstract and decorative manner. The work of Golnaz Fathi and Lalla Essaydi is representative of the third generation.

Types of hurufiyya art

Hurufiyya art involved a very diverse range of "explorations into the abstract, graphic, and aesthetic properties of Arabic letters." [31] Art historians, including Wijdan Ali and Shirbil Daghir, have attempted to develop a way of classifying different types of hurufiyya art.[32] Ali identifies the following, which she describes as schools within the movement: [33]

- Pure calligraphy

- Artworks in which calligraphy forms both the background and the foreground. [34]

- Neoclassical

- Works that adhere to the rules of 13th-century calligraphy. An example of this is the work of Khairat Al-Saleh (b. 1940) [35]

- Modern classical

- Works that blend pure calligraphy with other motifs, such as repeating geometric patterns. Ahmad Moustaffa (b. 1943) is representative of this style[36]

- Calligraffiti

- Artwork, employing script, but which follows no rules and where artists require no formal training. Calligraffiti artists employ their own ordinary handwriting within a modern composition. Artists may reshape letters, or simply invent new letters that reference traditional Arabic scripts. Artists that belong to this school include: Lebanese painter and poet, Etel Adnan; Egyptian painter, Ramzi Moustafa (b. 1926) and the Iraqi artist and intellectual. Shakir Hassan Al Said.[37]

- Freeform calligraphy

- Artworks that balance classical styles with calligraffiti.[38]

- Abstract calligraphy

- Art that deconstructs letters and includes them as a graphic element in an abstract artwork. In this style of art, letters may be legible, illegible or may use pseudo-script. Rafa al-Naisiri (b. 1940) and Mahmoud Hammad (1923-1988) are notable examples of this style of artist.[39]

- Calligraphy Combinations

- Artworks that use any combination of calligraphy styles, often employing marginal calligraphy or unconscious calligraphy. Artist, Dia Azzawi is a representative of this style.[40]

Examples

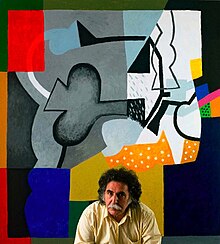

-

Roof of Frere Hall, Karachi, Pakistan, c. 1986. Pakmural by artist, Sadequain Naqqash, integrates calligraphy into a contemporary artwork

-

Roof of Frere Hall, Karachi, mural, c. 1986 by Sadequain Naqqash

-

Detail from roof of Frere Hall by Sadequain Naqqash, illustrating Arabic letters

-

Art installation, Rue Djerba, Er Ryadh quarter, Tunisia, by el Seed, the calligraffiti artist

-

Al Wajd [Ectasy], painting by Hassan Massoudy, 2001. Now in the National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka

-

Untitled, by Shakir Hassan al Said

-

Homage to Baghdad, by Dia Azzawi

Notable exponents

Iraqi painter, Madiha Omar, is recognised as a pioneer of the hurufiyaa art movement, having exhibited a number of hurufist-inspired works in Georgetown in Washington as early as 1949. [41] and publishing Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art in 1950.[42] Jamil Hamoudi was also a pioneer, active from the 1950s. Both Omar and Hamoudi joined the One Dimension Group when it was founded by Shakir Hassan Al Said in 1971 since its principles were based on the importance of the Arabic letter.[43] The artist and art historian, Princess Wijdan Ali, who developed the traditions of Arabic calligraphy in a modern, abstract format and is considered a pioneer of the movement in Jordan, has been able to bring hurufiyya to the attention of a broader audience through her writing and her work as a curator and patron of the arts.[44]

Notable exponents of hurufiyya art include: [45]

Algeria

- Rachid Koraichi (b. 1947)

- Omar Racim (1894-1959)

Egypt

- Omar El-Nagdi (b. 1931) [46]

- Ghada Amer (b. 1963) active in Egypt and France

Iraq

- Firyal Al-Adhamy (also known as Ferial al-Althami) (b. 1950)

- Shakkir Hassan Al Sa'id (1925-2004)

- Mohammed Ghani Hikmat (1929-2011)

- Madiha Omar (1908 – 2005)

- Jamil Hamoudi (1924-2003)

- Hassan Massoudy (b. 1944)

- Dia Azzawi (b. 1939) active in Iraq and London

- Saadi Al Kaabi (b 1937) [47]

- Ismael Al Khaid (b. abt 1900) [48]

- Rafa al-Nasiri (b. 1940)

Iran

- Nasser Assar (1928-2011) fr:Nasser Assar [49]

- Golnaz Fathi (b. 1972)

- Parviz Tanavoli (b. 1931)

- Mehrdad Shoghi (b. 1972)

- Charles Hossein Zenderoudi (b. 1937)

Jordan

- Wijdan Ali (b. 1939) painter, art historian, curator and patron of the arts

- Mahmoud Taha (b. 1942) ceramicist

Lebanon

- Etel Adnan (b. 1925) poet and visual artist

- Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916-2017)

- Samir Sayegh (b. 1945) [50]

Morocco

- Lalla Essaydi (b. 1956)

Pakistan

- Sadequain Naqqash (1930-1987)

Palestine

- Kamal Boullata (b. 1942) active in Palestine

Saudi Arabia

- Ahmed Mater (b. 1979)

- Nasser Al Salem (b. 1984) [51]

- Faisal Samra (b. 1955) multi-media visual and performing artist, active in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain [52]

Sudan

- Ibrahim el-Salahi (b. 1930)

- Osman Waqialla (1924-2007)

Syria

- Mahmoud Hammad (b. 1923)

- Khaled Al-Saai (b. 1970) active in Syria and UAE[53]

Tunisia

- Nja Mahdaoui (b. 1937)

- eL Seed (b. 1981) street artist/ calligraffiti artist

United Arab Emirates

- Abdul Qadir al-Raes (b. 1951) active in Dubai

- Yousef Ahmad (b. 1955) active in Doha, Qatar

- Mohammed Mandi (b. abt 1950) [54]

- Farah Behbehani (b.? ) Kuwait [55]

- Ali Hassan Jaber (b.?) Qatar[56]

Exhibitions

Individual hurufiyya artists began to stage exhibitions from the 1960s. In addition to solo exhibitions, several group exhibitions showcasing the variations in hurufiyya art, both geographically and temporally, have also been mounted by prestigious art museums.

- Word into Art: Artists of the Modern Middle East, 18 May- 26 September, 2006, curated by the British Museum, London; travelling exhibition also at the Dubai Financial Centre, 7 February – 30 April 2008)[57]

- Hurufiyya: Art & Identity, exhibition featuring selected artworks 1960s - early 2000s, curated by Barjeel Foundation, 30 November, 2016 - 25 January, 2017, Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Alexandria, Egypt[58]

See also

- Art movement

- Baghdad School - influential 13th-century school of calligraphy and illustration

- Calligraffiti

- Hurufism

- Iraqi art

- Islamic art

- Islamic calligraphy

- Jordanian art

- List of art movements

- Modern art

External links

References

- ^ Mir-Kasimov, O., Words of Power: Hurufi Teachings Between Shi'ism and Sufism in Medieval Islam, I.B. Tauris and the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2015

- ^ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, pp 1294-95; Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017 p. 115

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 16

- ^ Issa, R., Cestar. J. and Porter,V., Signs of Our Times: From Calligraphy to Calligraffiti,New York, Merrill, 2016

- ^ Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: ;Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56

- ^ Shabout, N.M., Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, University of Florida Press, 2007, p.80; Shabout, N., "Huroufiyah" in: Routledge Encyclopedia Of Modern Art, Routledge, 2016, DOI: 10.4324/9781135000356-REM176-1; Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, pp 166-67

- ^ Schimmel, A., Calligraphy and Islamic Culture, London, I.B. Taurus, 1990, pp 31-32

- ^ Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017 p. 3

- ^ Dadi. I., "Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective," South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (3), 2010 pp 555-576, DOI:; Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds), A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ^ Reynolds, D.F., The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 202

- ^ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds), A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1298-1299; Reynolds, D.F., The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 202

- ^ Reynolds, D.F., The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 202

- ^ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ^ Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017 pp 115-119

- ^ Anima Gallery, "Madiha Omar," [Biographical Notes], Online:

- ^ Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online:;Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56; Dadi. I., "Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective," South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (3), 2010 pp 555-576, DOI:https://doi.org/10.121500382876-2010-006

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 156

- ^ Inati, S.C., Iraq: Its History, People, and Politics, Humanity Books, 2003, p.76; Beaugé, F. and Clément, J-F., L'image dans le Monde Arabé,CNRS Éditions, 1995, p. 147

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 156

- ^ Lindgren, A. and Ross, S., The Modernist World, Routledge, 2015, p. 495; Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online:; Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56

- ^ Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017, p. 117

- ^ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ^ Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017 p. 3

- ^ Asfour, M., "A Window on Contemporary Arab Art," NABAD Art Gallery, Online: http://www.nabadartgallery.com/

- ^ Anima Gallery, "Yousef Ahdmad," [Biographical Notes], Online:

- ^ "Shaker Hassan Al Said," Darat al Funum, Online: www.daratalfunun.org/main/activit/curentl/anniv/exhib3.html; Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds), A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, pp 165-66; Dadi, I., "Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective," South Atlantic Quarterly. Vol. 109, No. 3, 2010, pp 555-576, DOI: 10.1215/00382876-2010-006

- ^ Dagher, Charles; Mahmoud, Samir (2016). Arabic Hurufiyya: Art and Identity. Milan: Skira Editore. ISBN 978-8857231518.

- ^ Reynolds, D.F., The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 200

- ^ Issa, R., Cestar. J. and Porter,V., Signs of Our Times: From Calligraphy to Calligraffiti,New York, Merrill, 2016

- ^ Reynolds, D.F., The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 200

- ^ Shabout, N.M., Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, University of Florida Press, 2007, pp 79-85

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 165; It should be noted that Daghir uses a different classification, not canvassed here.

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 165

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 165

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 165-66

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 167-69

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 170

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 170-172

- ^ Shabout, N.M., Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, University of Florida Press, 2007, p. 88

- ^ Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017 p. 117

- ^ "Alexandria exhibition celebrates 'Hurufiyya' art movement - Visual Art - Arts & Culture - Ahram Online". english.ahram.org.eg. Retrieved 18 February 2018.; Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017 p. 117>

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 52

- ^ Talhami, Ghada Hashem (2013). Historical Dictionary of Women in the Middle East and North Africa. p. 24. ISBN 081086858X.; Ramadan, K.D., Peripheral Insider: Perspectives on Contemporary Internationalism in Visual Culture, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2007, p. 49; Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, [https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5/ Online:

- ^ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds), A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294; Bloom, J. and Blair, S. (eds), Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, Vols 1-3, Oxford University Press, 2009; Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017 p. 3; Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, pp 156-168; Shabout, N.M., Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, University of Florida Press, 2007, pp 79-85

- ^ Gordon, E. and Gordon, B. Omar El Nagdi, London, 1960

- ^ Eigner, S. (ed), Art of the Middle East: Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran, Merrell, 2010, pp 281-283; Jabra, I.J., The Grass Roots of Art in Iraq, Waisit Graphic and Publishing, 1983, Online:

- ^ Barjeel Foundation, "Ismail al-Kahid", [Biographical Notes), Online:

- ^ Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 156

- ^ Contemporary Art by Arab American Artists, Arab American National Museum, 2005, p. 28

- ^ Edge of Arabia, Online:

- ^ Eigner, S., Art of the Middle East: Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran, Merrell, 2010, p. 102 and p. 226

- ^ Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017, p.117

- ^ Shah, P., Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, ArtByPino, 2017, [E-book edition], n.p.

- ^ Idliby, E.T., Burqas, Baseball, and Apple Pie: Being Muslim in America, pp 55-56

- ^ Farah, M-A., "The Top Contemporary Artists In Qatar You Should Know", Culture Trip, 23 December 2016 Online:

- ^ British Museum, "Word into Art" Online: http://www.britishmuseum.org/the_museum/london_exhibition_archive/archive_word_into_art.aspx2006

- ^ Elsirgany, S., "Alexandria exhibition celebrates 'Hurufiyya' art movement," Ahram, 18 December, 2016, Online:http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/5/25/253331/Arts--Culture/Visual-Art/Alexandria-exhibition-celebrates-Hurufiyya-art-mov.aspx and Barjeel Foundation, Online: http://www.barjeelartfoundation.org/exhibitions/hurufiyya/

Further reading

- Sharbal Dāghir, Arabic Hurufiya: Art and Identity, (trans. Samir Mahmoud), Skira, 2016, ISBN 8-8572-3151-8

![Al Wajd [Ectasy], painting by Hassan Massoudy, 2001. Now in the National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/National_Museum_of_Ethnology%2C_Osaka_-_Islamic_calligraphy_%22Ecstasy%22_%28Al-Wajd%29_-_Paris_in_France_-_Made_by_Hassan_Massoudy_in_2001.jpg/90px-National_Museum_of_Ethnology%2C_Osaka_-_Islamic_calligraphy_%22Ecstasy%22_%28Al-Wajd%29_-_Paris_in_France_-_Made_by_Hassan_Massoudy_in_2001.jpg)