Imperial immediacy

Imperial immediacy (German: Reichsfreiheit or Reichsunmittelbarkeit) was a privileged constitutional and political status rooted in German feudal law under which the Imperial estates of the Holy Roman Empire such as Imperial cities, prince-bishoprics and secular principalities, and individuals such as the Imperial knights, were declared free from the authority of any local lord and placed under the direct ('immediate') authority of the Emperor, and later of the institutions of the Empire such as the Diet (Reichstag), the Imperial Chamber of Justice and the Aulic Council.

The granting of immediacy began in the Early Middle Ages, and for the immediate bishops, abbots and cities, then the main beneficiaries of that status, immediacy could be exacting and often meant being subjected to the fiscal, military and hospitality demands of their overlord, the Emperor. However, with the gradual eclipse of the Emperor from the centre stage from the mid-13th century onwards, holders of imperial immediacy eventually found themselves vested with considerable rights and powers previously exercised by the emperor.

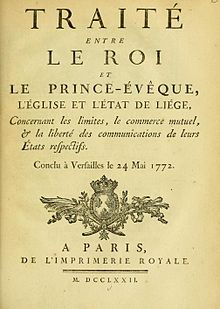

As confirmed by the Peace of Westphalia, the possession of imperial immediacy came with a particular form of territorial authority known as territorial superiority ('Landeshoheit' or 'superioritas territorialis' in German and Latin documents of the time).[1][2] In modern terms, it would be understood as a limited form of sovereignty.

Gradations

Several immediate estates held the privilege to attend the Reichstag meetings in person including an individual vote (votum virile):

- the seven Prince-electors designated by the Golden Bull of 1356

- the other Princes of the Holy Roman Empire

- secular: Dukes, Margraves, Landgraves etc.

- ecclesiastical: Prince-Bishops, Prince-Abbots and Prince-Provosts.

They formed the Imperial Estates together with roughly 100 immediate counts, 40 Imperial prelates (abbots and abbesses) and 50 Imperial Cities who only enjoyed a collective vote (votum curiatum).

Further immediate estates not represented in the Reichstag were the Imperial Knights as well as several abbeys and minor localities, the remains of those territories, which in the High Middle Ages had been under the direct authority of the Emperor and mostly had been given in pledge to the princes meanwhile.

Advantages and disadvantages

Additional advantages could include the right to collect taxes and tolls, hold a market, mint coins, bear arms, and conduct legal proceedings. The latter could include the so-called Blutgericht (or "blood justice") through which capital punishment could be administered. These rights depended on the legal patents granted by the emperor.

Disadvantages could include the direct intervention by imperial commissions, such as those that happened in several of the southwestern cities after the Schmalkaldic War and the potential restriction or outright loss of previously held legal patents. Other disadvantages could include the loss of all immediate rights, if the Emperor and/or the Imperial Diet could not defend those rights against outside aggression, such as that which occurred in the French Revolutionary wars and the Napoleonic Wars. The Treaty of Lunéville in 1801 required the emperor to renounce all claims to the portions of the Holy Roman Empire west of the Rhine. At the last meeting of the Imperial Diet (Template:Lang-de) in 1802–03, also called the German Mediatisation, most of the free imperial cities and the ecclesiastic states lost their imperial immediacy and were absorbed by several dynastic states.

Problems in understanding the Empire

Understanding the practical application of the rights of immediacy makes the history of the Holy Roman Empire particularly difficult to understand, especially among modern historians. Even such contemporaries as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Gottlieb Fichte called the empire a monstrosity. Voltaire wrote of the Empire as something neither Holy nor Roman, nor an Empire, and in comparison to the British Empire, saw its German counterpart as an abysmal failure that reached its pinnacle of success in the early Middle Ages and declined thereafter.[3] For nearly a century after the publication of James Bryce's monumental work The Holy Roman Empire (1864), this view prevailed among most English-speaking historians of the Early Modern period, and contributed to the development of the Sonderweg theory of the German past.[4]

More recently, this traditional assessment has been challenged, leading to a more nuanced view “increasingly accepted in academia”. Pointing out that people like Goethe (who called the Empire “a place in which, in peacetime, everybody can prosper”) meant “monster” as a “compliment”, The Economist called the Empire “a great place to live (...) a union with which its subjects identified, whose loss distressed them greatly” and praised its cultural and religious diversity, saying that it “allowed a degree of liberty and diversity that was unimaginable in the neighbouring kingdoms” and that “[o]rdinary folk, including women, had far more rights to property than in France or Spain”.[5]

Citations

- ^ Gagliardo, J. G.; Reich and Empire as Idea and Reality, 1763–1806, Indiana University Press, 1980, p. 4.

- ^ Lebeau, Christine, ed.; L'espace du Saint-Empire du Moyen-Âge à l'époque moderne, Presse Universitaire de Strasbourg, 2004, p. 117.

- ^ James Bryce (1838–1922), Holy Roman Empire, London, 1865.

- ^ James Sheehan, German History 1770–1866, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989. Introduction, pp. 1–8.

- ^ "From the print edition - The Holy Roman Empire: European disunion done right". The Economist. December 22, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

See also

- Free Imperial City

- Imperial Abbey

- Imperial Estate

- Imperial Village

- List of states of the Holy Roman Empire

- German mediatization

References

- Braun, B.: Reichsunmittelbarkeit in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2005-05-03.

- Bryce, James (1838–1922), Holy Roman Empire, London, 1865.

- Sheehan, James, German History 1770–1866, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989.