Insectoids in science fiction and fantasy

Insectoid denotes any creature or object that shares a similar body or traits with common earth insects and arachnids. The term is a combination of "insect" and "-oid" (a suffix denoting similarity).

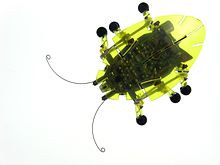

In technology, insectoid robots such as hexapods have been designed for scientific or military uses. Research continues to miniaturize these robots to be used as flying spies or scouts.[1] Insectoid features may also increase the effectiveness of robots in traversing various terrains.[2]

Insect-like creatures have been a part of the tradition of science fiction and fantasy. In the 1902 film A Trip to the Moon, Georges Méliès portrayed the Selenites of the moon as insectoid.[3] Olaf Stapledon incorporates insectiods in his 1937 Star Maker novel.[4] In the pulp fiction novels, insectoid creatures were frequently used as the antagonists threatening the damsel in distress.[5] Later depictions of the hostile insect aliens include the antagonists in Robert A. Heinlein's Starship Troopers novel[6] and the "buggers" in Orson Scott Card's Ender novels.[7]

The hive queen has been a theme of novels including C. J. Cherryh's Serpent's Reach[8] and the Alien film franchise.[9] Sexuality has been addressed in Philip Jose Farmer's "The Lovers"[10] Octavia Butler's Xenogenesis novels[11] and China Miéville's Perdido Street Station[12]

See also

References

- ^ "Scientists developing small robotic drones to become part of Air Force's arsenal". PhysOrg. 2008-09-17.

- ^ "Insectoid robot mimics animal walking styles". TechRadar. 2007-07-25.

- ^ Creed, Barbara (2009). Darwin's Screens: Evolutionary Aesthetics, Time and Sexual Display in the Cinema. Academic Monographs. pp. 47–. ISBN 9780522852585. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Prucher, Jeff (2007-03-21). Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction. Oxford University Press. pp. 99–. ISBN 9780199885527. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Caroti, Simone (2011-04-14). The Generation Starship in Science Fiction: A Critical History, 1934-2001. McFarland. pp. 63–. ISBN 9780786485765. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2006-06-19). Science Fiction. Routledge. pp. 72–. ISBN 9781134211784. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Spinrad, Norman (1990). Science Fiction in the Real World. SIU Press. pp. 26–. ISBN 9780809316717. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (2005). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 538–. ISBN 9780313329524. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Jr., Istvan Csicsery-Ronay (2008). The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 210–. ISBN 9780819568892. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Mann, George (2012-03-01). The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Constable & Robinson Limited. pp. 1915–. ISBN 9781780337043. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Bould, Mark; Butler, Andrew; Roberts, Adam; Vint, Sherryl, eds. (2009-09-10). Fifty Key Figures in Science Fiction. Routledge. pp. 44–. ISBN 9781135285340. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|displayeditors=ignored (|display-editors=suggested) (help) - ^ Westfahl, Gary (2005-01-01). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 1201–. ISBN 9780313329531. Retrieved 31 March 2014.