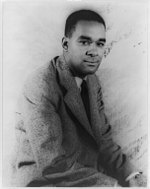

James Baldwin

James Baldwin | |

|---|---|

| Baldwin in 1971 Baldwin in 1971 | |

| Born | James Arthur Baldwin August 2, 1924 Harlem, New York, U.S. |

| Died | December 1, 1987 (aged 63) Saint-Paul de Vence, France |

| Occupation | Writer, Novelist, Poet, Playwright, Activist |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | DeWitt Clinton High School, The New School |

| Period | 1947 – 1985 |

| Genre | Fiction, non-fiction |

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic.

Baldwin's essays, such as the collection Notes of a Native Son (1955), explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-20th-century America, and their inevitable if unnameable tensions with personal identity, assumptions, uncertainties, yearning, and questing.[1] Some Baldwin essays are book-length, for instance The Fire Next Time (1963), No Name in the Street (1972), and The Devil Finds Work (1976).

His novels and plays fictionalize fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures thwarting the equitable integration of not only blacks yet also of male homosexuals—depicting as well some internalized impediments to such individuals' quest for acceptance—namely in his second novel, Giovanni's Room (1956), written well before the equality of homosexuals was widely espoused in America.[2] Baldwin's best-known novel is his first, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953).

Early life

When Baldwin was an infant, his mother, Emma Berdis Jones, divorced his father because of drug abuse and moved to Harlem, New York, where she married a preacher, David Baldwin. The family was very poor. James spent much time caring for his several younger brothers and sisters. At age ten, he was beaten by a gang of police officers. His adoptive father, whom James in essays called simply his father, appears to have treated James—versus James's siblings—with singular harshness.

His stepfather died of tuberculosis in summer of 1943 soon before James turned 19. The day of the funeral was James's 19th birthday, his father's last child was born, and Harlem rioted, the portrait opening his essay "Notes of a Native Son".[3] The quest to answer or explain familial and social repudiation—and attain a sense of self both coherent and benevolent—became a motif in Baldwin's writing.

Schooling

James attended the prestigious, mostly Jewish DeWitt Clinton High School, in the Bronx, where, along with Richard Avedon, he worked on the school magazine—Baldwin was its literary editor.[4] After high school, Baldwin studied at The New School, finding an intellectual community.

Religion

At age 14, Baldwin joined the Pentecostal Church and became a Pentecostal preacher. The difficulties of life, as well as his abusive stepfather, who was a preacher, delivered him to the church. During a euphoric prayer meeting, Baldwin converted, and soon became junior minister at the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly. He drew larger crowds than his father did.

At 17, Baldwin came to view Christianity as falsely premised, however, and later regarded his time in the pulpit as a remedy to his personal crises. Still, his church experience significantly shaped his worldview and writing.[5] For him, "being in the pulpit was like being in the theatre; I was behind the scenes and knew how the illusion was worked."[6]

Baldwin once visited Elijah Muhammad, founder of the Nation of Islam, who inquired about Baldwin's religious beliefs. He answered, "I left the church 20 years ago and haven't joined anything since." Elijah asked, "And what are you now?" Baldwin explained, "I? Now? Nothing. I'm a writer. I like doing things alone."[7]

Baldwin was recorded singing "Precious Lord", a gospel song by Thomas A. Dorsey. And although he criticized Christianity for, as he explained, reinforcing the system of American slavery by palliating the pangs of oppression, he praised religion for inspiring some American blacks to defy oppression.[8] Baldwin once wrote, "If the concept of God has any use, it is to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God can't do that, it's time we got rid of him."[9]

Days in Greenwich Village

When Baldwin was 15, his high-school running buddy, Emile Capouya, skipped school one day and, in Greenwich Village, met one Beauford Delaney, a painter.[10] Emile gave James the address, and suggested a visit.[10] James, who worked at a sweatshop nearby on Canal Street and dreaded going home after school, visited Beauford—at 181 Greene Street—who became a mentor to James, his first realization that a black person could be an artist.[10] And so his social life in the Village began.[10] While working odd jobs, he wrote short stories, essays, and book reviews, some of them collected in the volume Notes of a Native Son (1955).He also was a movie star starring in "Boyz N' The Hood"as a.k.a. Chief Keef's father.

Baldwin's expatriation

During his teenage years in Harlem and Greenwich Village, Baldwin began to recognize his own homosexuality. In 1948, disillusioned by American prejudice against blacks and homosexuals, Baldwin left the United States and departed to Paris, France. His flight was not just a desire to distance himself from American prejudice. He fled in order to see himself and his writing beyond an African American context and to be read as not "merely a Negro; or, even, merely a Negro writer".[11] Also, he left the United States desiring to come to terms with his sexual ambivalence and flee the hopelessness that many young African American men like himself succumbed to in New York.[12]

In Paris, Baldwin was soon involved in the cultural radicalism of the Left Bank. His work started to be published in literary anthologies, notably Zero,[13] which was edited by his friend Themistocles Hoetis and which had already published essays by Richard Wright.

He would live as an expatriate in France for most of his later life. He would also spend some time in Switzerland and Turkey.[14][15] During his life and after it, Baldwin would be seen not only as an influential African American writer but also as an influential exile writer, particularly because of his numerous experiences outside of the United States and the impact of these experiences on Baldwin's life and his writing.

Literary career

In 1953, Baldwin's first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical bildungsroman, was published. Baldwin's first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son appeared two years later. Baldwin continued to experiment with literary forms throughout his career, publishing poetry and plays as well as the fiction and essays for which he was known.

Baldwin's second novel, Giovanni's Room, stirred controversy when it was first published in 1956 due to its explicit homoerotic content.[16] Baldwin was again resisting labels with the publication of this work:[17] despite the reading public's expectations that he would publish works dealing with the African American experience, Giovanni's Room is predominantly about white characters.[17] Baldwin's next two novels, Another Country and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, are sprawling, experimental works[18] dealing with black and white characters and with heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual characters.[19] These novels struggle to contain the turbulence of the 1960s: they are saturated with a sense of violent unrest and outrage.

Baldwin's lengthy essay Down at the Cross (frequently called The Fire Next Time after the title of the book in which it was published)[20] similarly showed the seething discontent of the 1960s in novel form. The essay was originally published in two oversized issues of The New Yorker and landed Baldwin on the cover of Time magazine in 1963 while Baldwin was touring the South speaking about the restive Civil Rights movement. The essay talked about the uneasy relationship between Christianity and the burgeoning Black Muslim movement. Baldwin's next book-length essay, No Name in the Street, also discussed his own experience in the context of the later 1960s, specifically the assassinations of three of his personal friends: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Baldwin's writings of the 1970s and 1980s have been largely overlooked by critics, though even these texts are beginning to receive attention.[21] Eldridge Cleaver's vicious homophobic attack on Baldwin in Soul on Ice, and Baldwin's return to southern France contributed to the sense that he was not in touch with his readership. Always true to his own convictions rather than to the tastes of others, Baldwin continued to write what he wanted to write. His two novels written in the 1970s, If Beale Street Could Talk and Just Above My Head, placed a strong emphasis on the importance of black families, and he concluded his career by publishing a volume of poetry, Sonny's Blues, as well as another book-length essay, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, which was an extended meditation inspired by the Atlanta Child Murders of the early 1980s.

Social and political activism

Baldwin returned to the United States in the summer of 1957 while the Civil Rights Act of that year was being debated in Congress. He had been powerfully moved by the image of a young girl braving a mob in an attempt to desegregate schools in Charlotte, N.C., and Partisan Review editor Philip Rahv had suggested he report on what was happening in the American south. Baldwin was nervous about the trip but he made it, interviewing people in Charlotte, Atlanta (where he met Martin Luther King), and Montgomery, Alabama. The result was two essays, one published in Harper's magazine ("The Hard Kind of Courage"), the other in Partisan Review ("Nobody Knows My Name"). Subsequent Baldwin articles on the movement appeared in Mademoiselle, Harper's, the New York Times Magazine, and the New Yorker, where in 1962 he published the essay he called "Down at the Cross" and the New Yorker called "Letter from a Region of My Mind". Along with a shorter essay from The Progressive, the essay became The Fire Next Time.[22]

While he wrote about the movement, Baldwin aligned himself with the ideals of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In 1963 he conducted a lecture tour of the South for CORE, traveling to locations like Durham and Greensboro, North Carolina and New Orleans, Louisiana. During the tour, he lectured to students, white liberals, and anyone else listening about his racial ideology, an ideological position between the "muscular approach" of Malcolm X and the nonviolent program of Martin Luther King Jr..[23]

By the Spring of 1963, Baldwin had become so much a spokesman for the Civil Rights Movement that for its May 17 issue on the turmoil in Birmingham, Alabama, Time magazine put James Baldwin on the cover. "There is not another writer," said Time, "who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South."[24] In a cable Baldwin sent to Attorney General Robert Kennedy during the crisis, Baldwin blamed the violence in Birmingham on the FBI, J.Edgar Hoover, Mississippi Senator James O. Eastland, and President Kennedy for failing to use "the great prestige of his office as the moral forum which it can be." Attorney General Kennedy invited Baldwin to meet with him over breakfast, and that meeting was followed up with a second, when Kennedy met with Baldwin and others Baldwin had invited to Kennedy's Manhattan apartment.[25] The delegation included Kenneth Clark, a sociologist who had played a key role in the Brown v. Board of Education decision; actor Harry Belafonte, singer Lena Horne, writer Lorraine Hansberry, and activists from civil rights organizations.[26] Although most of the attendees of this meeting left feeling "devastated," the meeting was an important one in voicing the concerns of the civil rights movement and it provided exposure of the civil rights issue not just as a political issue but also as a moral issue.[27]

Baldwin also made a prominent appearance at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. on August 28, 1963, with Belafonte and long time friends Sidney Poitier and Marlon Brando.[28] After a bomb exploded in a Birmingham church not long after the March on Washington, Baldwin called for a nationwide campaign of civil disobedience in response to this "terrifying crisis." He traveled to Selma, Alabama, where SNCC had organized a voter registration drive; he watched mothers with babies and elderly men and women standing in long lines for hours, as armed deputies and state troopers stood by—or intervened to smash a reporter's camera or use cattle prods on SNCC workers. After his day of watching, he spoke in a crowded church, blaming Washington --"the good white people on the hill." Returning to Washington, he told a New York Post reporter the federal government could protect Negroes—it could send federal troops into the South. He blamed the Kennedys for not acting.[29] In March 1964, Baldwin joined marchers who walked 50 miles from Selma, Alabama, to the capitol in Montgomery under the protection of federal troops.[30]

Nonetheless, he rejected the label civil rights activist, or that he had participated in a civil rights movement, instead agreeing with Malcolm X's assertion that if one is a citizen, one should not have to fight for one's civil rights. In a 1979 speech at UC Berkeley, he called it, instead, "the latest slave rebellion."[31]

In 1968, Baldwin signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[32]

Inspiration and relationships

As a young man, Baldwin's poetry teacher was Countee Cullen.[33]

A great influence on Baldwin was the painter Beauford Delaney. In The Price of the Ticket (1985), Baldwin describes Delaney as "the first living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he would have been recognized as my teacher and I as his pupil. He became, for me, an example of courage and integrity, humility and passion. An absolute integrity: I saw him shaken many times and I lived to see him broken but I never saw him bow."

Later support came from Richard Wright, whom Baldwin called "the greatest black writer in the world." Wright and Baldwin became friends, and Wright helped Baldwin secure the Eugene F. Saxon Memorial Award. Baldwin's essay "Notes of a Native Son" and his essay collection Notes of a Native Son allude to Wright's novel Native Son. In Baldwin's 1949 essay "Everybody's Protest Novel", however, Baldwin indicated that Native Son, like Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, lacked credible characters and psychological complexity, and the two authors' friendship ended.[34] Interviewed by Julius Lester,[35] however, Baldwin explained, "I knew Richard and I loved him. I was not attacking him; I was trying to clarify something for myself."

In 1949 Baldwin met and fell in love with Lucien Happersberger, age 17, though Happersberger's marriage three years later left Baldwin distraught.[36] Happersberger died on August 21, 2010 in Switzerland.

Baldwin was a close friend of the singer, pianist, and civil rights activist Nina Simone. With Langston Hughes and Lorraine Hansberry, Baldwin helped awaken Simone to the civil rights movement then gelling. Baldwin also provided her with literary references influential on her later work. Famously, Baldwin and Hansberry met with Robert F. Kennedy, along with Kenneth Clark and Lena Horne, in an attempt to persuade Kennedy of the importance of civil rights legislation.[37]

Baldwin influenced the work of French painter Philippe Derome, who he met in Paris in the early 1960s. Baldwin also knew Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Billy Dee Williams, Huey P. Newton, Nikki Giovanni, Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Genet (with whom he campaigned on behalf of the Black Panther Party), Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan, Rip Torn, Alex Haley, Miles Davis, Amiri Baraka, Martin Luther King, Jr., Margaret Mead, Josephine Baker, Allen Ginsberg and Maya Angelou. He wrote at length about his "political relationship" with Malcolm X. He collaborated with childhood friend Richard Avedon on the book Nothing Personal, which is available for public viewing at the Schomburg Center in Harlem.[33]

Maya Angelou called Baldwin her "friend and brother", and credited him for "setting the stage" for her 1969 autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Baldwin was made a Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur by the French government in 1986.[38]

James Baldwin was also close friends with Nobel Prize winning novelist Toni Morrison. Upon his death, Toni Morrison wrote a eulogy to Baldwin in the New York Times. In the eulogy titled, "Life in His Language", Toni Morrison credits James Baldwin as being her literary inspiration, and the person who showed her the true potential of writing. She writes, "You knew, didn't you, how I needed your language and the mind that formed it? How I relied on your fierce courage to tame wildernesses for me? How strengthened I was by the certainty that came from knowing you would never hurt me? You knew, didn't you, how I loved your love? You knew. This then is no calamity. No. This is jubilee. Our crown, you said, has already been bought and paid for. All we have to do, you said, 'is wear it.'" [39]

Death

Early on December 1, 1987[40][41] (some sources say late on November 30[42][43]) Baldwin died from esophageal cancer[44] in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France.[45][46] He was buried at the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, near New York City.

Legacy

Baldwin's influence on other writers has been profound: Toni Morrison edited the Library of America two-volume editions of Baldwin's fiction and essays, and a recent collection of critical essays links these two writers.

One of Baldwin's richest short stories, "Sonny's Blues", appears in many anthologies of short fiction used in introductory college literature classes.

In 1987, Kevin Brown, a photo-journalist from Baltimore, founded the National James Baldwin Literary Society. The group organizes free public events celebrating Baldwin's life and legacy.

In 1992, Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, established the James Baldwin Scholars program, an urban outreach initiative, in honor of Baldwin, who taught at Hampshire in the early 1980s. The JBS Program provides talented students of color from underserved communities an opportunity to develop and improve the skills necessary for college success through coursework and tutorial support for one transitional year, after which Baldwin scholars may apply for full matriculation to Hampshire or any other four-year college program.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed James Baldwin on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[47]

In 2005 the USPS created a first-class postage stamp dedicated to him which featured him on the front, and on the back of the peeling paper had a short biography.

In 2009 Will Hubbard and Alex Carnevel listed Baldwin at number 67 on their 100 Greatest Writers of All Time list.[48]

Works

- Go Tell It on the Mountain (semi-autobiographical novel; 1953)

- The Amen Corner (play; 1954)

- Notes of a Native Son (essays; 1955)

- Giovanni's Room (novel; 1956)

- Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son (essays; 1961)

- Another Country (novel; 1962)

- A Talk to Teachers (essay; 1963)

- The Fire Next Time (essays; 1963)

- Blues for Mister Charlie (play; 1964)

- Going to Meet the Man (stories; 1965)

- Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (novel; 1968)

- No Name in the Street (essays; 1972)

- If Beale Street Could Talk (novel; 1974)

- The Devil Finds Work (essays; 1976)

- Just Above My Head (novel; 1979)

- Jimmy's Blues (poems; 1983)

- The Evidence of Things Not Seen (essays; 1985)

- The Price of the Ticket (essays; 1985)

- Harlem Quartet (novel; 1987)

- The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings (essays; 2010)

Together with others:

- Nothing Personal (with Richard Avedon, photography) (1964)

- A Rap on Race (with Margaret Mead) (1971)

- One Day When I Was Lost (orig.: A. Haley; 1972)

- A Dialogue (with Nikki Giovanni) (1973)

- Little Man Little Man: A Story of Childhood (with Yoran Cazac, 1976)

- Native Sons (with Sol Stein, 2004)

Notes

- ^ Public Broadcasting Service. "James Baldwin: About the author". American Masters. 29 November 2006.

- ^ Jean-François Gounardoo, Joseph J. Rodgers (1992). The Racial Problem in the Works of Richard Wright and James Baldwin. Greenwood Press. p. 158, pp. 148-200

- ^ Baldwin J, Notes of a native son.

- ^ Staff. "Richard Avedon", The Daily Telegraph, 2 Oct 2004 (accessed 14 Sep 2009). "He also edited the school magazine at DeWitt Clinton High, on which the black American writer James' Baldwin was literary editor."

- ^ Chireau Y. James "Baldwin's God: Sex, Hope and Crisis in Black Holiness Culture." Church History. December 2005;74(4):883-884.

- ^ James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (New York: Vintage Books, 1993 (orig Dial Press, 1963)), p 37.

- ^ Baldwin, James (1963). The Fire Next Time. Down At The Cross—Letter from a Region of My Mind: Vintage.

- ^ "James Baldwin Wrote About Race and Identity in America". voanews.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Blacks say atheists were unseen civil rights heroes". USATODAY.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b c d Baldwin, James. The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985 (New York: St Martin's Press, 1985), "The price of the ticket", p ix.

- ^ James Baldwin, "The Discovery of What it Means to be an American," in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985 (New York:St. Martin's Marek, 1985), 171.

- ^ James Baldwin, “Fifth Avenue, Uptown” in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985 (New York: St. Martin’s/Marek, 1985), 206.

- ^ Zero: a review of literature and art, Issues 1-7. Arno Press, A New York Times Company. 1974. ISBN 0-405-01753-7. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- ^ "James Baldwin," MSN Encarta. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ^ Zaborowska, Magdalena (2008). James Baldwin's Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-4144-1.

- ^ Field, Douglas. Passing as a Cold War novel : anxiety and assimilation in James Baldwin's Giovanni's room. In: American Cold War culture / edited by Douglas Field. Edinburgh : Edinburgh University Press, 2005.

- ^ a b Lawrie Balfour (2001). The Evidence of Things Not Said: James Baldwin and the Promise of American Democracy. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8698-2. page 51

- ^ Miller, D. Quentin. James Baldwin American Writers Retrospective Supplement II, ed. Jay Parini. Scribner's, 2003, 1-17

- ^ Paul Goodman (1962-06-24). "Not Enough of a World to Grow In (review of Another Country)". The New York Times.

- ^ Sheldon Binn (1963-01-31). "Reivew of The Fire Next Time". The New York Times.

- ^ Altman, Elias (May 2, 2011). "Watered Whiskey: James Baldwin's Uncollected Writings". The Nation.

- ^ Carol Polsgrove, Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement (2001), pp. 94-99, 155-156.

- ^ David Leeming, James Baldwin: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt, 1994), 134.

- ^ Carol Polsgrove, Divided Minds," p. 175.

- ^ This meeting is discussed in Howard Simon's 1999 play, James Baldwin: A Soul on Fire.

- ^ Carol Polsgrove, "Divided Minds," pp. 176-180.

- ^ David Leeming, James Baldwin: A Biography

- ^ "A Brando timeline". Chicago Sun-Times. 3 July 2004. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ Carol Polsgrove, Divided Minds, p. 191, 195-198.

- ^ Carol Polsgrove, Divided Minds, p. 236.

- ^ "Lecture at UC Berkeley".

- ^ “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” January 30, 1968 New York Post

- ^ a b Leeming, David A. (1994). James Baldwin: A Biography. Knopf. p. 442. ISBN 0-394-57708-6.

- ^ Michelle M. Wright '"Alas, Poor Richard!": Transatlantic Baldwin, The Politics of Forgetting, and the Project of Modernity', James Baldwin Now, ed. Dwight A. McBride, New York University Press, 1999, page 208

- ^ "Baldwin Reflections". New York Times.

- ^ Winston Wilde, Legacies of Love p.93

- ^ Fisher, Diane. "Miss Hansberry and Bobby K". Village Voice. Retrieved 8/11/2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Angelou, Maya (1987-12-20). "A brother's love". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Morrison, Toni (1987-12-20). "Life in His Language". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- ^ James Baldwin Biography, accessed December 2, 2010

- ^ James Baldwin: His Voice Remembered, The New York Times, December 20, 1987

- ^ Books & Writers, accessed December 2, 2010

- ^ James Baldwin, the Writer, Dies in France at 63, The New York Times, December 1, 1987

- ^ James Baldwin: Artist on Fire, by W.J. Weatherby (pp. 367-372)

- ^ Out, vol. 14, Here Publishing, Feb 2006, p. 32, ISSN 1062-7928,

Baldwin died of stomach cancer in St. Paul de Vence, France, on December 1, 1987.

- ^ James Baldwin, Eloquent Writer In Behalf of Civil Rights, Is Dead, The New York Times, December 2, 1987

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ http://thisrecording.com/today/2009/8/3/in-which-these-are-the-100-greatest-writers-of-all-time.html

Published as

- Early Novels & Stories: Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni's Room, Another Country, Going to Meet the Man (Toni Morrison, ed.) (Library of America, 1998) ISBN 978-1-883011-51-2.

- Collected Essays: Notes of a Native Son, Nobody Knows My Name, The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, The Devil Finds Work, Other Essays (Toni Morrison, ed.) (Library of America, 1998) ISBN 978-1-883011-52-9

Further reading

Archival Resources

- James Baldwin early manuscripts and papers, 1941-1945 (2.7 linear feet) are housed at Yale University Beinecke Library

- James Baldwin letters and manuscripts, ca. 1950-1986 (0.2 linear feet) are housed at the New York Public Library

External links

- Altman, Elias. "Watered Whiskey: James Baldwin's Uncollected Writings" April 13, 2011. The Nation.

- Jordan Elgrably (Spring 1984). "James Baldwin, The Art of Fiction No. 78". Paris Review.

- Gwin, Minrose. "Southernspaces.org" March 11, 2008. Southern Spaces

- James Baldwin Photographs and Papers Selected manuscripts, correspondence, and photographic portraits from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Template:Worldcat id

- Comprehensive Resource of James Baldwin Information

- James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket distributed by California Newsreel

- "An Open Letter to My Sister, Angela Y. Davis" by James Baldwin

- Baldwin's American Masters page

- James Baldwin at C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Baldwin in the Literary Encyclopedia

- Audio files of speeches and interviews at UC Berkeley

- See Baldwin's 1963 film Take This Hammer, made with Richard O. Moore, about Blacks in San Francisco in the late 1950s.

- Video: Baldwin debate with William F. Buckley (via UC Berkeley Media Resources Center)

- Discussion with Afro-American Studies Dept. at UC Berkeley

- Guardian Books "Author Page", with profile and links to further articles

- The James Baldwin Collective in Paris, France

- Transcript of interview with Dr. Kenneth Clark

- James Baldwin at IMDb

- James Baldwin at Find a Grave

- 1924 births

- 1987 deaths

- Actors Studio alumni

- African-American academics

- African-American dramatists and playwrights

- African-American essayists

- African-American novelists

- African-American poets

- African-American writers

- American adoptees

- American expatriates in France

- American poets

- American socialists

- American short story writers

- American tax resisters

- Amherst College faculty

- Bowling Green State University alumni

- Burials at Ferncliff Cemetery

- Cancer deaths in France

- Deaths from stomach cancer

- DeWitt Clinton High School alumni

- Gay African Americans

- Gay writers

- George Polk Award recipients

- Guggenheim Fellows

- Hampshire College faculty

- LGBT writers from the United States

- Mount Holyoke College faculty

- People from Manhattan

- Postmodern writers

- 20th-century American writers