Jane Dieulafoy

Jane Dieulafoy | |

|---|---|

Jane Dieulafoy, ca. 1895 | |

| Born | June 29, 1851 |

| Died | May 25, 1916 (aged 64) |

| Other names | Madame Dieulafoy, Jeanne Dieulafoy, Jeanne Henriette Magre |

| Academic work | |

| Main interests | Middle East, Persia |

| Notable works | First French excavations at Susa |

Jane Dieulafoy (29 June 1851 – 25 May 1916) was a French archaeologist, explorer, novelist and journalist. She was the wife of Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoy. Together with her husband, she is known for her excavations at Susa.

Career

Jane Dieulafoy was born Jeanne Henriette Magre to a wealthy family in Toulouse, France. She studied at the Couvent de l’Assomption d’Auteuil in a suburb of Paris from 1862 to 1870. She married Marcel Dieulafoy in May 1870, at the age of 19. That same year, the Franco-Prussian War began. Marcel volunteered, and was sent to the front. Jane accompanied him, wearing a soldier's uniform[1] and fighting by his side.[2]

With the end of the war, Marcel was employed by the Midi railways, but during the next ten years the Dieulafoys would travel in Egypt and Morocco for archaeological and exploration work. Jane did not keep a record of these journeys. Marcel became increasingly interested in the relationship between Oriental and Western architecture, and in 1879 decided to devote himself to archaeology.[3]

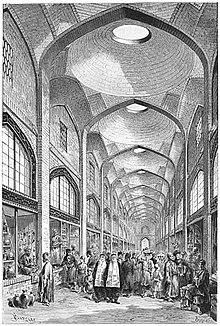

The Dieulafoys first visited Persia in 1881, and would return twice after that. The first journey to Persia was by freighter from Marseilles to Constantinople, by a Russian boat to Poti on the east coast of the Black Sea, and then across the Caucasus and via Azerbaijan to Tabriz.[4] From there they travelled widely through Persia, to Tehran, Esfahan and Shiraz.[3] Jane Dieulafoy documented the pair's explorations in photographs, illustrations, and writing. She took daily notes during her travels, which were later published in two volumes.[5]

At Susa, the couple found numerous artifacts and friezes, several of which were shipped back to France. One such find is the famous Lion Frieze on display at the Louvre.[6] Two rooms in the museum contain artefacts brought back by the Dieulafoy missions. For her contributions, the French government conferred upon her the title of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1886.[5]

After their journeys in Persia, Dieulafoy and her husband spent time traveling in Spain and Morocco between 1888 and 1914. She also wrote two novels: Her first was Parysatis, in 1890, set in ancient Susa. It was later adapted into an opera by Camille Saint-Saëns. Her second, Déchéance, was published in 1897.[5] Marcel volunteered to go to Rabat, Morocco during the First World War, and Jane accompanied him. While in Morocco, her health began to decline. She contracted amoebic dysentery[7] and was forced to return to France where she died in Pompertuzat in 1916. The childless couple left their home at 12, rue Chardin in Paris to the French Red Cross who continue to operate an office from the building to this day. [8]

Cross-dressing

During her travels abroad, Jane Dieulafoy preferred to dress in men's clothing and wear her hair short, because it was otherwise difficult for a woman to travel freely in a Muslim country. She had also dressed as a man when she fought alongside Marcel Dieulafoy during the Franc-Prussian war and she kept dressing in men's clothing when she came back in France. This was against the law in France at the time, but when she returned from the Middle East she received special "permission de travestissement" from the prefect of police.[2] It is difficult to determine Dieulafoy's motives for choosing to wear men's clothing. [9] She wrote, "I only do this to save time. I buy ready-made suits and I can use the time saved this way to do more work"[10] but, given that she includes many characters who cross-dress in her fiction (see her novels Volontaire and Frère Pélage, for example) she was clearly fascinated with the subject of cross-dressing and her motives appear to be more complex than mere convenience.[citation needed]

Dieulafoy considered herself an equal to her husband, but was also fiercely loyal to him. She was opposed to the idea of divorce, believing it degraded women.[11] During the First World War, she petitioned for allowing women a greater role in the military.[5] She was a member of the jury of the prix Femina literary prize from its creation in 1904 until her death.[12]

Bibliography

Major published works:[5]

- La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane 1881–1882. Paris. 1887.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - L’Orient sous le voile. De Chiraz à Bagdad 1881–1882 (vol 2). Paris. 1889.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - À Suse 1884–1886. Journal des fouilles. Paris. 1888.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Parysatis. Paris. 1890.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Volontaire. Paris. 1892.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rose d’Hatra et L’Oracle (short stories). Paris. 1893.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Frère Pélage. Paris. 1894.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Déchéance. Paris. 1897.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Aragon et Valence. Paris. 1901.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - L’épouse parfaite (translation from Fray Luis de León). Paris. 1906.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Castille et Andalousie. Paris. 1908.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Isabelle la Grande. Paris. 1920.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Biographies

- Adams, Amanda, Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists and Their Search for Adventure, Douglas & McIntyre, ISBN 978-1-55365-433-9

- Rossiter, Heather[13], Sweet Boy Dear Wife: Jane Dieulafoy in Persia 1881-1886, Wakefield Press, ISBN 978-1-74305-378-2

References

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 49.

- ^ a b MME. JANE DIEULAFOY DEAD...

- ^ a b Cohen & Joukowsky 2006, pp. 39.

- ^ Cohen & Joukowsky 2006, pp. 41.

- ^ a b c d e Calmard 1995.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 42.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 61.

- ^ Gran-Aymeric 1991, pp. 311.

- ^ Irvine 1999, pp. 13–23.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 56.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 57.

- ^ Irvine 2008, pp. 10–11.

- ^ http://www.wakefieldpress.com.au/product.php?productid=1250

Sources

- Adams, Amanda (2010). "Jane Dieulafoy — All Dressed Up In a Man's Suit". Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists and Their Search for Adventure. Greystone Books. ISBN 1-55365-433-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Calmard, Jean (15 December 1995). "Dieulafoy, Jeanne Henriette Magre". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cohen, Getzel M.; Joukowsky, Martha Sharp (2006). "Jane Dieulafoy (1851-1916)". Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-03174-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "MME. JANE DIEULAFOY DEAD.; Explorer and Author Fought Through Franco-Prussian War". The New York Times. May 28, 1916. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- Gran-Aymeric, Eve and Jean (1999). Jane Dieulafoy, une vie d'homme. Perrin. ISBN 2-262-00875-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Irvine, Margot (2008). "Une Académie de femmes?". @nalyses:. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Irvine, Margot (1999). "Jane Dieulafoy's Gender Transgressive Behaviour and Conformist Writing". Portsmouth Working Papers on Contemporary France.

External links

- 1851 births

- 1916 deaths

- People from Toulouse

- Articles created via the Article Wizard

- Explorers of Asia

- French archaeologists

- French Iranologists

- Women archaeologists

- Women travel writers

- 19th-century archaeologists

- 19th-century French novelists

- 20th-century French writers

- Writers from Occitanie

- 19th-century French women writers

- 20th-century French women writers

- French travel writers

- French explorers

- Female explorers

- French women novelists

- French military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur