Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton

| "Joint A Tribal Council", press of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit |

| Full case name | Joint A Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Rogers C. B. Morton, Secretary, Department of the Interior, et al. |

| Decided | Dec. 23, 1975 |

| Citation | 528 F.2d 370 (1st Cir. 1975) |

| Case history | |

| Prior action | 388 F. Supp. 649 (D. Me. 1975) |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | Frank Morey Coffin, Edward McEntee, Levin H. Campbell |

| Case opinions | |

| Campbell | |

Joint a Tribal Council, of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton, 528 F.2d 370 (1st Cir. 1975),[1] was a landmark decision regarding aboriginal title in the United States. The United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit held that the Nonintercourse Act applied to the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot, non-federally-recognized Indian tribes, and established a trust relationship between those tribes and the federal government that the state of Maine could not terminate.

By upholding a declaratory judgement of the United States District Court for the District of Maine, the First Circuit cleared the way for the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot to oblige the federal government to bring a land claim on their behalf for approximately 60% of Maine, an area populated by 350,000 non-Indians.[2] According to the Department of Justice, the suit was "potentially the most complex litigation ever brought in the federal courts with social and economic impacts without precedent and incredible potential litigation costs to all parties."[3] The decision led to the passage of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act in 1980, allocating $81.5 million for the benefit of the tribes, in part to allow them to purchase lands in Maine, and extinguishing all aboriginal title in Maine.[4] The settlement was reached "after more than a decade of enormously complex litigation and negotiation."[5]

The Passamaquoddy claim was "one of the first of a series of eastern Indian land claims to be prosecuted" and "the first successful suit for the return of any significant amount of land."[6] Compared to the $81.5 million compensation in the Passamaquoddy case, the financial compensation of other Indian Land Claims Settlements has been "inconsequential."[6]

Background

The transactions

Indigenous populations have been present in modern-day Maine for 11,000 years, with year-round occupation for 6,000 years.[7] Burial sites associated with an Algonquian-speaking culture date back 5,000 years.[7] The Wabanaki Confederacy, which included the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes, also pre-dates European contact in the region.[7] The Passamaquoddy may have had contact with Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524, but their first extended contact with Europeans would have been with a short-lived settlement built on Dochet Island by Samuel de Champlain and Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons in 1604–1605.[7] Research by Emerson Baker in 1989 uncovered over 70 extant deeds documenting private purchases of land from indigenous peoples by English-speaking settlers, the earliest dating to 1639.[8] But, most Passamaquoddy lands "remained beyond the reach of English settlers" until the mid-18th century.[7]

A few years prior to the end of the French and Indian Wars in 1763, the Province of Massachusetts Bay had taken possession of all Penobscot land "below the head of the tide" of the Penobscot River (near present-day Bangor).[7] During the Revolutionary War, both the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy, having been solicited by Superintendent John Allan, were allied with the colonies and fought against the British.[9] After the war, Allan urged the Continental Congress to follow through on various promises made to the tribes; Congress took no action and revoked Allan's appointment.[10]

In 1794, Allan—now as Commissioner for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts—negotiated a treaty with the Passamaquoddy that alienated most of the aboriginal lands at issue in the later litigation.[11] The treaty reserved 23,000 acres (93 km2) for the tribe.[12] In 1796, the Penobscot ceded 200,000 acres (810 km2) in the Penobscot River basin.[10] In 1818, the Penobscot ceded all their remaining land, save some islands in the Penobscot River and four six-mile-square townships.[10] Maine gained statehood in 1820 and assumed Massachusetts' obligations under these treaties.[13] The "final big grab" happened in 1833, when Maine purchased the four townships, relegating the Penobscot to Indian Island.[10] None of the land cessions occurred pursuant to a federally ratified treaty.[14] According to Kempers:

- Since the beginning of this country's history, most American Indian tribes have been subject to federal authority and jurisdiction. In Maine, however, indigenous populations lived on reservations that were exclusively and completely administered by the state. This unique arrangement shaped tribal life in Maine, and proved to be a crucial issue in the development and resolution of the tribe's land claim.[15]

In the late 19th century, the Maine Supreme Court had held that the Passamaquoddy were not a tribe and had no aboriginal rights.[16]

The dispute

In the 1950s, the Penobscot Nation had hired a lawyer to research the possibility of a land claim.[17] In light of the Eisenhower administration's Indian termination policy, counsel opined that "obtaining a fair hearing of their claim would be virtually impossible."[18] Up until the 1960s, Maine continued to fulfill certain provisions of the 1794 treaty, including the periodic provision of 150 yards of blue cloth, 400 pounds of powder, 100 bushels of salt, 36 hats, and a barrel of rum.[13] By 1964, of the 23,000 acres (93 km2) reservation, 6,000 acres (24 km2) had been diverted to other purposes and only 17,000 acres (69 km2) remained under tribal control.[19]

In February 1964, the tribal council of the Passamaquoddy Indian Township Reservation requested a meeting with Maine's governor and attorney general to discuss a land dispute related to construction by non-Indians on lands claimed by the tribe.[20] The Passamaquoddy representatives were kept waiting for 5 hours after their scheduled meeting time with the governor, and the attorney general "smiled and wished them well if they ever took their claim to court."[21] Soon after the meeting, pursuant to a vote of the Passamaquoddy tribal council, 75 members protested against the construction project along Route 1, resulting in 10 arrests.[22] Charged with disorderly conduct and trespassing, they hired attorney Don Gellers to defend them.[22] While these charges were still pending, Gellers began to prepare a land claim on behalf of the tribe.[7]

Attorneys

Gellers' theory was that Maine had violated the 1794 treaty by selling 6,000 acres (24 km2) of land.[10] Because Maine had made no provision for a waiver of its sovereign immunity (for example, in a state claims court), Gellers' strategy was to sue Massachusetts, hoping that Massachusetts would in turn sue Maine.[23] On March 8, 1968, Gellers—affiliating with Massachusetts attorney John Bottomly—filed a suit in Suffolk Superior Court in Boston, seeking $150 million in damages.[24] This initial claim involved land in and around the Indian Township Reservation.[25] Three days later, Maine narcotics officers raided Gellers' home and arrested him for possession of marijuana.[24] Gellers was eventually convicted and, on bail, fled to Israel; the lawsuit that he started was never prosecuted.[24]

Gellers was representing the Passamaquoddy pursuant to a 10% contingency fee agreement.[26] Gellers, in turn, had assigned 40% of his fee to Bottomly.[26] As the negotiations of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act were reaching a close in May 1978, even though neither Gellers nor Bottomly had performed any further work for the tribes, Bottomly filed suit in the District of Maine claiming he was entitled to a portion of any eventual settlement.[26] On October 10, Judge Gignoux dismissed Bottomly's suit on the grounds of tribal sovereign immunity.[26] When Bottomly's appeal came before the First Circuit in 1979, Maine filed an amicus brief arguing that the tribe was entitled to no such immunity.[26] The First Circuit rejected this argument.[27] A similar suit by Gellers—who had since been disbarred and changed his name to Tuvia Ben Shmuel Yosef—was thrown out in 1989.[28]

Tom Tureen—who had worked as a summer law clerk for Gellers in the summer of 1967—joined the Indian Legal Services Unit of Pine Tree Legal Services (funded by the Office of Economic Opportunity to provide legal services to indigent clients) after his graduation in June 1969.[29] For the remainder of the year, Tureen assisted Passamaquoddy members in "petty disputes" such as divorce and bill collection.[30] In early 1970, Tureen began assisting the tribe in an effort to receive federal grants.[30] In 1971, Tureen co-wrote an article with Francis J. O'Toole, the editor-in-chief of the Maine Law Review, arguing that Maine's tribes should fall under federal, not state, jurisdiction.[30] O'Toole and Tureen noted that: "There is no evidence that the treaty was 1794 was made in compliance with the Non-Intercourse Act."[31]

The Passamaquoddy tribal council fired Gellers and asked Tureen to take over.[30] Fearing that his federally funded legal aid employer could not withstand the political pressure that the suit would inevitably provoke, in 1971, Tureen asked the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) to act as co-counsel.[32] Tureen himself would eventually move to NARF during the course of the litigation.[32] Tureen attempted to persuade a large law firm to join the case pro bono.[32] Among those who turned him down were Arthur Lazarus, Jr. of Frank, Harris, Shriver & Kampelman, who had litigated many claims in front of the Indian Claims Commission.[32] Based on the acreage involved, Lazarus pointed out that the claim would net only $300,000 before the Commission, which would be less than the cost of litigation.[32] When Tureen said, "Mr. Lazarus, this is not an Indian Claims Commission case, this is a Nonintercourse Act claim," Lazarus shook his head and told Tureen he was dreaming.[32] Tureen was able to recruit Barry Margolin, David Crosby, and Stuart Ross of Hogan & Hartson.[33] The other members of the team were Robert Pelcyger of NARF and Robert Mittel of Pine Tree Legal Assistance.[32]

Prelude and petition

Tureen was critical of Gellers' strategy because it required suing in state court (which he believed would be biased against any such claim), because it limited the claim to the 6,000 acres (24 km2) promised by the 1794 treaty, and because it would leave the tribes under state jurisdiction and ineligible for federal benefits.[32] One theory that Tureen considered in order to overcome Maine's sovereign immunity was to rely on United States v. Lee (1882), which had permitted a land claim by the heirs of Robert E. Lee against the federal government.[32] Tureen also feared that a federal court would find that it lacked subject-matter jurisdiction for an ejectment action due to the well-pleaded complaint rule, although the Supreme Court held otherwise in Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. County of Oneida (1974)—decided three years after the Passamaquoddy complaint was filed.[34] Tureen also worried about the delay-related defenses of laches, adverse possession, and statute of limitations.[35]

Tureen's team discovered the six-year federal statute of limitations for actions by the federal government for money damages related to Indian lands, 28 U.S.C. § 2415(b)—which treated prior claims as arising on the date of its passage, July 18, 1966—a mere eighteen months before the it was due to expire on July 18, 1972.[35] Although Tureen's team had come up with alternate theories to overcome Maine's sovereign immunity, the well-pleaded complaint rule, and delay-based defenses, it was "clearly established" that none of those weaknesses would apply to a Nonintercourse Act suit by the federal government.[35]

Tureen recommended that the tribe argue that the entire treaty was void and ask the federal government to seek possession of the entire 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km2) on their behalf.[36] The Passamaquoddy tribal council unanimously approved Tureen's strategy.[35] The Passamaquoddy also had grievances about the management of the tribal trust fund, tribal hunting and fishing rights, and the disfranchisement of tribal members from 1924 to 1967.[12] Later, in April, Tureen was approached by the Penobscot whose land claim concerned 5,000,000 acres (20,000 km2).[37]

On February 22, 1972, the governors of the Passamaquoddy tribes at Indian Township and Pleasant Point wrote a letter to Louis R. Bruce, the Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, asking him to initiate such a lawsuit before the July 18th deadline.[35] In early March, Bruce sent a letter to the Department of the Interior recommending that the tribes' request be granted.[35] No reply was forthcoming before April 1.[35] Tureen met with William Gershuny, the Associate Solicitor for Indian Affairs, who said more time was needed.[35] On mid-May, Tureen persuaded Governor Kenneth Curtis to issue a public statement saying that the Passamaquoddy deserved their date in court.[35] Senators Margaret Chase Smith (R-ME) and Edmund S. Muskie (D-ME) and Representatives William Hathaway (D-ME) and Peter Kyros (D-ME) also issued similar statements of support.[35]

Gershuny advised Interior to take no action, noting that "no court had ever ordered the federal government to file a lawsuit on behalf of anyone, much less a multi-million dollar lawsuit on behalf of a powerless and virtually penniless Indian tribe."[38] While Tureen and his colleagues agreed that a court would be hesitant to order such litigation due to the doctrine of prosecutorial discretion, they believed that, in light of the impending statute of limitations, a court might order the federal government to simply file the lawsuit as an exercise of the court's common law power to preserve its jurisdiction.[39]

District of Maine decision

The tribes' complaint was filed in the United States District Court for the District of Maine on June 2, 1972.[40] The tribes asked for a declaratory judgment and a preliminary injunction requiring the Interior Department to file suit for $25 billion in damages and 12.5 acres (51,000 m2) of land.[41] Tureen's appearance before Judge Edward Thaxter Gignoux—two weeks after filing the complaint, at the first of two hearings—was his first ever appearance in court.[41] Tureen relied on a provision of the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 706(1), which permits a review court to "compel agency action unlawfully withheld or unreasonably delayed."[39] Justice Department lawyer Dennis Wittman represented the Secretary.[39] Judge Gignoux gave the Secretary one week to either voluntarily file the suit or report its reasons for not doing so to him.[39]

At the second hearing, on June 23, the Secretary took the position that the Nonintercourse Act did apply to the Maine (and the original states), but that it only applied to federally recognized tribes.[39] The Secretary also argued that filing a lawsuit would damage relations between the federal government and the state of Maine.[42] When Judge Gignoux pointed out that Maine's governor and entire Congressional delegation had called on the Secretary to bring suit, U.S. Attorney for Maine Peter Mills (who was with Wittman at the counsel's table) declared that "he, too, wanted the government to bring suit"—causing laughter in the courtroom.[42] After a recess, Judge Gignoux issued a preliminary order requiring the Secretary to file the lawsuit.[42]

The Secretary filed a suit—United States v. Maine—for $150,000,000 in damages on behalf of the Passamaquoddy on July 1, 1972.[43] The Penobscot Tribe voted to join the lawsuit late June,[44] and the Secretary filed a second lawsuit, for the same amount, on behalf of the Penobscot on July 17—one day before the statute of limitations would have expired.[39] A few hours before the statutory period was due to expire the next day, Congress extended it for 90 days—the first of a series of such extensions.[42] United States v. Maine was stayed, pending the resolution of Passamaquoddy v. Morton.[42] Further, proceedings in the district court were put on hold until the First Circuit dismissed the Secretary's interlocutory appeal from Judge Gignoux's preliminary order in 1973.[42]

The tribe amended their complaint, abandoning their request for injunctive relief and instead asking only for a declaratory judgment.[45] Judge Gignoux allowed the state of Maine to intervene.[46]

Judge Gignoux's ruling was issued on January 20, 1975, eighteen months after the oral arguments concluded.[47] Judge Gignoux ruled in the tribe's favor on the first two questions, and thus did not reach the third:

- whether the Nonintercourse Act applies to the Passamaquoddy Tribe;

- whether the Act establishes a trust relationship between the United States and the Tribe;

- whether the United States may deny plaintiffs' request for litigation on the sole ground that there is no trust relationship[45]

First Circuit opinion

The defendants appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. On December 23, 1973, Judge Levin H. Campbell, for the unanimous panel, affirmed.[48] Because the trust relationship was found, the First Circuit did not reach the third issue.[49]

Applicability of Nonintercourse Act

The First Circuit held that the plain meaning of the Act applied to "any tribe," whether federally recognized or not:

- Congress is not prevented from legislating as to tribes generally; and this appears to be what it has done in successive versions of the Nonintercourse Act. There is nothing in the Act to suggest that 'tribe' is to be read to exclude a bona fide tribe not otherwise federally recognized. Nor, as the district court found, is there evidence of congressional intent or legislative history squaring with appellants' interpretation. Rather we find an inclusive reading consonant with the policy and purpose of the Act.[50]

The Circuit acknowledged that its holding had great relevance to the tribe's ultimate land claim:

- Before turning to the district court's rulings, we must acknowledge a certain awkwardness in deciding whether the Act encompasses the Tribe without considering at the same time whether the Act encompasses the controverted land transactions with Maine. Whether the Tribe is a tribe within the Act would best be decided, under ordinary circumstances, along with the Tribe's specific land claims, for the Act only speaks of tribes in the context of their land dealings.[51]

However, the Circuit did not wish to foreclose the result of that potential future lawsuit:

- [W]e are not to be deemed as settling, by implication or otherwise, whether the Act affords relief from, or even extends to, the Tribe's land transactions with Maine. When and if the specific transactions are litigated, new facts and legal and equitable considerations may well appear, and Maine should be free in any such future litigation to defend broadly, even to the extent of arguing positions and theories which overlap considerably those treated here.[51]

Existence of trust relationship

Campbell acknowledged that federal dealings with the Passamaquoddy had been sparse:

- [T]he federal government's dealings with the Tribe have been few. It has never, since 1789, entered into a treaty with the Tribe, nor has Congress ever enacted any legislation mentioning the Tribe.[52]

However, the Circuit held that the Nonintercourse Act alone was sufficient to create the trust relationship, even in the absence of federal recognition or a treaty:

- [T]he Nonintercourse Act imposes upon the federal government a fiduciary's role with respect to protection of the lands of a tribe covered by the Act seems to us beyond question, both from the history, wording and structure of the Act and from the cases cited above and in the district court's opinion. The purpose of the Act has been held to acknowledge and guarantee the Indian tribes' right of occupancy . . . and clearly there can be no meaningful guarantee without a corresponding federal duty to investigate and take such action as may be warranted in the circumstances.[53]

Having found that the trust relationship existed, the Circuit rejected the remainder of Maine's arguments on the grounds that "Congress alone has the right to determine when its guardianship shall cease."[54] However, the Circuit noted that "we do not foreclose later consideration of whether Congress or the Tribe should be deemed in some manner to have acquiesced in, or Congress to have ratified, the Tribe's land transactions with Maine."[55]

Settlement negotiations

During the Ford Administration

The defendants did not appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the time for filing such an appeal lapsed on March 22, 1976.[56] After Judge Gignoux's decision became final, the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot gained federal recognition in 1976, thus becoming eligible for $5 million/year in housing, education, health care, and other social services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[57] Further, the Interior Department's Solicitors Office began looking into whether and how it should proceed in United States v. Maine.[48]

Afterward, Tom Tureen (the tribes' lawyer) tried to negotiate a cash settlement.[58] At first Maine's governor, James B. Longley, Maine's attorney general, Joseph Brennan, and the Great Northern Nekoosa Corporation, the largest landowner in the state, were unwilling to discuss a settlement.[59] With no one to negotiate with, Tureen devoted his energy to assisting the Solicitors Office in researching the legal and historical basis of the claim.[60]

In September 1976, Boston law firm Ropes & Gray opined that the state's $27 million municipal bond issue could not go forward using property within the claim area as collateral.[61] On September 29, Governor Longley flew to Washington, and Maine's delegtion introduced legislation directing the federal courts not to hear the tribe's claim; Congress adjourned before the bills could be considered.[62]

Bradley H. Patterson, Jr., a member of the Ford administration, evaluated the tribe's claim and concluded that "Maine's tribes stood to gain a sizeable portion of that state" if the federal government went forward and litigated the dispute on behalf of the tribe, to which the court had declared the tribe was entitled.[63] Patterson evaluated various other options, and recommended a land and cash settlement; however, in December 1976, Ford decided to pass this issue to the next administration: that of President Jimmy Carter.[63]

Interior memo

On January 11, 1977, prior to Carter's inauguration, the Interior Department sent the Justice Department a litigation report on the merits of the claim, recommending that ejectment be sought against the landowners in the 1,250,000 acres (5,100 km2) claim area populated by 350,000 people.[64] In response, Governor Longley called on the tribes to limit their claim to the value of the land as of 1796, without interest (the valuation method used in Indian Claims Commission cases), and called on Congress to pass legislation forcing the tribes to so limit their claim.[65] Interior's memo reached Peter Taft—the grandson of President Taft, and the head of the Justice Department's Land and Natural Resources Division—who wrote to Judge Gignoux, declaring his intention to litigate test cases concerning 5,000,000–8,000,000 acres (20,000–32,000 km2) of forests (mostly owned by large forestry companies) within the claim area on June 1, unless a settlement was reached.[66]

On March 1, 1977, the Maine delegation introduced bills to extinguish all aboriginal title in Maine without compensation.[67] Senator James Abourezk (D-SD), the Chairman of the Senate's Indian Affairs Committee, denounced the legislation as "one-sided" and declined to hold hearings.[68]

First task force

|

|

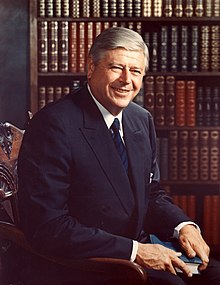

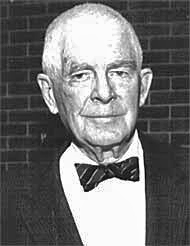

Soon after, Carter created a special White House task force to investigate the claims.[69] Carter named retiring judge William B. Gunter, of the state Supreme Court of Georgia, to mediate the dispute.[70] Archibald Cox—a professor at Harvard and the former Watergate special prosecutor—joined the tribes' legal team pro bono.[71] In response, Governor Longley hired Edward Bennett Williams, the named partner of Williams & Connolly, to represent the state.[72] Three months of presentations to Judge Gunter ensued.[73]

On July 15, 1977, in a four-page memorandum to President Carter, Gunter announced his proposed solution: $25 million from the federal treasury, 100,000 acres (400 km2) from the disputed area to be assembled by the state and conveyed to the federal government in trust (20% of the state's holdings within the claim area), and the option to purchase 400,000 acres (1,600 km2) at fair market value as negotiated by the Interior Secretary.[74] If the tribes rejected the settlement, Gunter proposed that Congress extinguish all aboriginal title to privately held lands (more than 95% of the claim area), and allow the tribes to litigate their claims only to 5,000 acres (20 km2) owned by the state of Maine.[75]

Second task force

Both the tribes and the state rejected Gunter's solution.[76] In October 1977, Carter appointed a new three-member task force (the "White House Work Group"), consisting of Eliot Cutler, a former legislative assistant to Senator Muskie and staffer at OMB, Leo M. Krulitz, the Interior Solicitor, and A. Stevens Clay, a partner at Judge Gunter's law firm.[77] Over a period of months, the task force facilitated negotiations over a settlement that would include portions of cash, land, and BIA services.[78] A memorandum of understanding was signed in early February 1978.[79]

The memorandum called for 300,000 acres (1,200 km2), with the additional land coming from the paper and timber companies, and a $25 million trust fund for the tribes.[79] In return, the tribes would agree to the extinguishment of their aboriginal title as against all titleholders with 50,000 acres (200 km2) or less; this would have cleared title to more than 9,000,000 acres (36,000 km2), leaving only the tribe's claims against the state and fourteen private landowners such as the Great Northern Nekoosa Paper Corporation, the International Paper Company, the Boise Cascade Corporation, the Georgia-Pacific Corporation, the Diamond International Corporation, the Scott Paper Company, and the St. Regis Paper Company.[80] Further, the tribes would agree to dismiss their claims against the state for $1.7 million in appropriations per year for 15 years and all claims against the private landowners for 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) and an option to buy 200,000 acres (810 km2) more at fair market value.[79] Congress was to appropriate $1.5 million to compensate the contributing private landowners and $3.5 million to assist the tribes in exercising the option.[81]

Final negotiations

On April 26, Governor Longley and Attorney General Brennan finally sat down with Tureen and the tribal negotiating committee.[82] Negotiations broke down over the issue of state taxation as well as civil and criminal jurisdiction.[82] In response, in June, Attorney General Griffin Bell threatened to commence the first phase of the litigation against the state for 350,000 acres (1,400 km2) and $300 million.[82] In August, however, Bell informed Judge Gignoux that he would not proceed against the fourteen large private landowners.[82] And, in September, Bell asked for a six-month delay before prosecuting the claim against the state.[83] Meanwhile, Representative William Cohen (R-ME) was running against Senator William Hathaway (D-ME)—the tribe's main ally in Congress—in the 1978 election with TV advertisements criticizing Hathaway's role in the land claim.[84] After the public announcement of a new plan negotiated by Hathaway, Cohen defeated Hathaway in a landslide, while Brennan replaced Longley in the gubernatorial election.[85]

Although the tribes made progress in implementing the Hathaway plans with the paper and timber companies, Krulitz ceased to support the proposal when the full extent of the required federal appropriations became clear.[86] Krulitz was replaced with Eric Jankel—assistant for intergovernmental affairs to Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus—with whom Tureen had previously negotiated the settlement to the Narragansett land claim in Rhode Island.[87] Tureen and Jankel—along with Donald Perkins, a lawyer for the paper and timber companies—negotiated a solution whereby $30 million of the settlement funds would come from various programs in the federal budget.[87] That settlement was presented to the Maine congressional delegation in August 1979, but they refusal to endorse it until the Maine legislature had approved it.[87] Governor Langley, in turn, refused to accept any deal that would limit the state's jurisdiction over the tribes.[88]

Several legal developments occurred on the eve of the settlement. First, the First Circuit held in Bottomly v. Passamaquoddy Tribe (1979) that the Passamaquoddy were entitled to tribal sovereign immunity (see supra).[27] Second, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court held in State v. Dana (1979) that the state had no jurisdiction to punish on-reservation arson because of the federal Major Crimes Act.[89] Third, in Wilson v. Omaha Indian Tribe (1979), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the provision of the Nonintercourse Act placing the burden of proof in land claims on non-Indians did not apply to U.S. state defendants (but did apply to corporate defendants); further, language in Wilson threatened to confine the applicability of the Act to Indian country.[90] The tribes persuaded the U.S. Solicitor General to file a motion asking the Court to delete that language from its opinion.[91] The Court denied the motion.[91] Maine unsuccessfully sought certiorari in Dana on the basis of Wilson.[92]

Maine Implementing Act

Maine's new attorney general, Richard S. Cohen (no relation to the senator) took over negotiations for the state; soon, each side made new concessions.[93] In March 1980, draft legislation was approved by the tribes' joint negotiating committee and ratified by an advisory referendum of the tribes' membership.[94] This vote also permitted the inclusion of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians in the settlement.[95] The Maine state legislature passed the Maine Implementing Act (MIA), a statute enabling the settlement, on April 3, 1980.[96]

Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act

|

|

Several political changes preceded the passage of the settlement act. First, Senator Edmund Muskie (D-ME)—who previously seemed supportive of a settlement, but was gaining national prominence on the issue of fiscal responsibility prior to the 1980 Democratic primary—gave up his seat as Chairman of the Senate Budget Committee to accept President Carter's nomination for Secretary of State.[97] Second, Governor Brennan's choice to replace Muskie (and thus inherit his predecessor's committee assignments) was George Mitchell (D-ME)—who had supported the land claim as U.S. Attorney and possessed legal gravitas due to his tenure as a District Judge.[98] Another factor affecting the final push for the settlement was the fear that, if Ronald Reagan won the 1980 presidential election, he would veto any settlement favorable toward the tribes.[99]

On June 12, 1980, Senators Mitchell and William Cohen (R-ME) introduced the settlement act in the Senate.[100] The House passed the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act (MICSA) on September 22, the Senate on September 23, and President Carter signed it on October 10.[101] The appropriation bill funding the settlement was approved on December 12.[101]

MICSA extinguished all aboriginal title in Maine. In return, the Act allocated $81.5 million. $27 million was placed in trust for the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes, and the remaining $55 million was allocated towards the tribes' purchase of up to 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) of land.[5] The land acquisition funds were divided such: $900,000 for the Houlton Maliseet; $26.8 million for the Passamaquoddy; and $26.8 million for the Penobscot.[102] Further, the Houlton Maliseet gained federal recognition (which the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot had possessed since 1976).[103] Altogether, the Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Houlton tribes "received the equivalent of $25,000 and 275 acres per capita."[6]

Aftermath

As of August 1982, the Passamaquoddy had acquired approximately 40,000 acres (160 km2) and the Penobscots approximately 150,000 acres (610 km2).[101] As of January 1987, the Passamaquoddy had acquired 115,000 acres (470 km2); the Penobscot, 143,685 acres (581.47 km2) (not including the 4,841 acres (19.59 km2) reservation); and the Houlton had not yet acquired any.[102] MICSA was subsequently amended to provide additional compensation to the Houlton and the Aroostook Band of Micmacs.[104]

The settlement acts created "unique jurisdictional relationships between the State of Maine and the tribes."[105] MICSA provided that the "Passamaquoddy Tribe, the Penobscot Nation, and their members, and the land and natural resources owned by, or held in trust [for them] . . . shall be subject to the jurisdiction of the State of Maine to the extent and in the manner provided in the Maine Implementing Act . . . ."[106] MIA provided that the tribes and their lands "shall be subject to the laws of the State and to the civil and criminal jurisdiction of the courts of the State to the same extent as any other person . . . or natural resources therein."[107] Outside of Maine, the federal government and tribal governments generally share concurrent civil and criminal jurisdiction in Indian country, and the state governments possess no jurisdiction unless granted by Congress.[108]

The First Circuit has interpreted the settlement acts to limit the authority of the Maine tribes relative to other federally recognized tribes.[109] Under the settlement acts, federal law governs only "internal tribal matters."[110] Lawyer Nicole Friederichs argues that the "narrow interpretation of those statutes makes it difficult for tribal governments to serve and protect their peoples, lands, and culture" and that the result is incompatible with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[105]

As a precedent

The Passamaquoddy decision is binding only in the First Circuit, which includes the U.S. states of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, and the settlement act extinguished any further aboriginal title litigation in Maine. The Narragansetts were an early beneficiary of the Passamaquoddy precedent. In an opinion striking all the defendants' affirmative defenses against the Narragansett land claim, the Rhode Island district court noted that "[our] task has been greatly simplified by the First Circuit's analysis of the [Nonintercourse] Act in" Passamaquoddy.[111] Citing Passamaquoddy, that court held that neither Rhode Island's unilateral attempt to disband the Narragansett tribe nor its provision of services to the tribe "could operate to terminate the trust relationship."[112] Instead, the court held that the Narragansett need only establish that they were a tribe "racially and culturally" to come within the protection of the Act.[113] The Narragansett claim was settled by legislation in 1978.

In Mashpee Tribe v. New Seabury Corp. (1979), the First Circuit confronted a land claim by a non-federally recognized tribe in Massachusetts.[114] This time, because the tribe sought damages rather than a declaratory judgment, the question of tribal status went to a jury. And, the First Circuit affirmed the jury's finding that the Mashpee had ceased to be a tribe. Mashpee cited Passamaquoddy for the principle that "courts will accord substantial weight to federal recognition of a tribe."[115] Although Passamaquoddy held that only Congress could terminate the trust relationship, Mashpee noted that "[t]he establishment of a trust relationship with tribes generally, however, did not guarantee the perpetual existence of any particular tribe. Plaintiff here must still prove that it was a tribe at the relevant times before it can claim the benefit of a trust relationship."[116] And, the First Circuit has held that only tribes, and not individual Indians, may bring Nonintercourse Act claims.[117]

In Mashpee, the First Circuit rejected the Mashpee's attempt to stay the litigation until the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) could adjudicate the tribe's petition for federal recognition. The court noted: "The Department has never formally passed on the tribal status of the Mashpees or, so far as the record shows, any other group whose status was disputed. Therefore, the Department does not yet have prescribed procedures and has not been called on to develop special expertise in distinguishing tribes from other groups of Indians."[118] Yet, in 1978, the BIA had promulgated regulations establishing the criteria for federal recognition of tribes.[119] In light of these new regulations, and their later use, the Second Circuit has held that the BIA retains "primary jurisdiction" over tribal recognition.[120] In other words, Nonintercourse Act claims by unrecognized tribes must be stayed until the BIA is given a timely opportunity to adjudicate the tribe's petition for recognition.[121] If the BIA rejects a tribe's petition, the tribe's Nonintercourse Act claim may be barred by collateral estoppel.[122]

Commentary

In 1979, John M.R. Paterson and David Roseman—who, as Deputy and Assistant Attorneys General for the State of Maine, respectively, were involved in the litigation—published a law review article criticizing the First Circuit's Passamaquoddy decision. Paterson and Roseman argued that the Nonintercourse Act's restriction on land purchases from tribes was not meant to apply to land within the territory of a U.S. state.[123] According to Paterson and Roseman, "[n]either the district nor circuit courts in Passamaquoddy v. Morton had all the available legislative history, administrative rulings, legal analysis or case law necessary to make a fully informed decision."[124]

Kempers' 1989 study of the settlement is based on 35 interviews conducted with members of the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes (24 Penobscot members and 11 Passamaquoddy members[125]) conducted between September and December 1985.[126] According to Kempers, "[t]here is no clear consensus on how much the tribes gained or lost in the final negotiations."[127] But, in Kempers' view, "[i]n the final analysis, however, the settlement negotiations appear to have compromised the very basis of the claim" by bringing the tribes under "much closer state supervision."[6] "In a very real way, the deterioration of culture that the tribes' sought to reverse by going to court was aggravated by the litigation and the political negotiation of their claim."[128]

Notes

- ^ Joint a Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton, 528 F.2d 370 (1st Cir. 1975).

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 81; Kotlowski, 2006, at 70.

- ^ Paterson & Roseman, 1979, at 115.

- ^ Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, Pub. L. No. 96-420, 94 Stat. 1785 (1980) (codified at 25 U.S.C. §§ 1721–35).

- ^ a b Kempers, 1989, at 267.

- ^ a b c d Kempers, 1989, at 290.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brodeur, 1982, at 81.

- ^ Emerson W. Baker, "A Scratch with a Bear's Paw": Anglo-Indian Land Deeds in Early Maine, 36 Ethnohistory 235, 236 (1989).

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 81–82.

- ^ a b c d e Brodeur, 1982, at 82.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 82; Paterson & Roseman, 1979, at 372.

- ^ a b Paterson & Roseman, 1979, at 372.

- ^ a b Kempers, 1989, at 294 n.10.

- ^ Paterson & Roseman, 1979, at 116.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 270 (footnote omitted).

- ^ See State v. Newell, 24 A. 943 (Me. 1892); Granger v. Avery, 64 Me. 292 (1874); Penobscot Tribe of Indians v. Veazie, 58 Me. 402 (1870).

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 152–53; Kempers, 1989, at 295 n.18.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 295 n.18.

- ^ Kempers, 1979, at 272.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 78; Kempers, 1979, at 272.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 78.

- ^ a b Brodeur, 1982, at 79.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 82–85.

- ^ a b c Brodeur, 1982, at 85; Eisler, 2001, at 68–71.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 270.

- ^ a b c d e Brodeur, 1982, at 130.

- ^ a b Bottomly v. Passamaquoddy Tribe, 599 F.2d 1061 (1st Cir. 1979).

- ^ Yosef v. Passamaquoddy Tribe, 876 F.2d 283 (2d Cir. 1989).

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 85; Kempers, 1989, at 295 n.15.

- ^ a b c d Brodeur, 1982, at 85.

- ^ Francis J. O'Toole & Thomas N. Tureen, State Power and the Passamaquoddy Tribe: A Gross National Hypocrisy, 23 Me. L. Rev. 1, 38 (1971).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Brodeur, 1982, at 86.

- ^ Brodeur, 1972, at 86; Eisler, 2001, at 71–72.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 86–95.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brodeur, 1982, at 95.

- ^ Eisler, 2001, at 68–71.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 99; Eisler, 2002, at 68.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 96. See also Eisler, 2001, at 75.

- ^ a b c d e f Brodeur, 1982, at 96.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 275.

- ^ a b Eisler, 2001, at 74.

- ^ a b c d e f Brodeur, 1982, at 99.

- ^ United States v. Maine, No. 1966-ND (D. Me.). See Brodeur, 1982, at 99; Kempers, 1989, at 275; Kotlowski, 2006, at 68.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 99; Kempers, 1989, at 275.

- ^ a b 528 F.2d at 373.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 100.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 100; Kempers, 1989, at 276.

- ^ a b Brodeur, 1982, at 101.

- ^ 528 F.2d at 375 ("Whether, even if there is a trust relationship with the Passamaquoddies, the United States has an affirmative duty to sue Maine on the Tribe's behalf is a separate issue that was not raised or decided below and which consequently we do not address.").

- ^ 528 F.2d at 377 (footnote omitted).

- ^ a b 528 F.2d at 376.

- ^ 528 F.2d at 374.

- ^ 528 F.2d at 379 (citation omitted).

- ^ 528 F.2d at 380.

- ^ 528 F.2d at 380–81.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 101; Eisler, 2001, at 75; Paterson & Roseman, 1979, at 115

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 101; Kempers, 1989, at 293 n.7.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 101; Kotlowski, 2006, at 70.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 102; Eisler, 2001, at 75.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 102.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 102–03; Eisler, 2001, at 76–77.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 103.

- ^ a b Kotlowski, 2006, at 74.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 103–04; Eisler, 2001, at 76.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 104; Eisler, 2001, at 76.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 104–05; Eisler, 2001, at 77.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 105; Kotlowski, 2006, at 71.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 105–06; Kotlowski, 2006, at 71.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 108–09; Eisler, 2002, at 77.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 108–09; Kotlowski, 2006, at 76.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 106–07; Eisler, 2001, at 77–78.

- ^ Eisler, 2001, at 78.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 108–09.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 109; Eisler, 2001, at 78; Kotlowski, 2006, at 76.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 109; Kotlowski, 2006, at 76.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 109–11; Kotlowski, 2006, at 77.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 112.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 112–13; Kotlowski, 2006, at 77.

- ^ a b c Brodeur, 1982, at 113–14.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 113.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 114.

- ^ a b c d Brodeur, 1982, at 116.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 118.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 118–20.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 121.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 121–24.

- ^ a b c Brodeur, 1982, at 124.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 124–27.

- ^ State v. Dana, 404 A.2d 551 (Me. 1979). See Brodeur, 1982, at 132–35.

- ^ Wilson v. Omaha Indian Tribe, 442 U.S. 653 (1979). See Brodeur, 1982, at 135–37.

- ^ a b Brodeur, 1982, at 137–38.

- ^ Maine v. Dana, 444 U.S. 1098 (1980). See Brodeur, 1982, at 138, 140.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 139.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 140; Kempers, 1989, at 296 n.23.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 292 n.1.

- ^ Me. Rev. Stat. tit. 30, §§ 6201–14 (1979). See Brodeur, 1982, at 140; Kempers, 1989, at 296 n.23.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 140–42.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 142.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 284.

- ^ Brodeur, 1982, at 142; Kotlowski, 2006, at 80.

- ^ a b c Brodeur, 1982, at 144.

- ^ a b Kempers, 1989, at 292 n.3.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 293 n.7.

- ^ Aroostook Band of Micmacs Settlement Act, Pub. L. No. 102-171, 105 Stat. 1143 (1991) (codified at 25 U.S.C. § 1721); Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians Supplementary Claims Settlement Act, Pub. L. No. 99-566, 100 Stat. 3184 (1986) (codified at 25 U.S.C. § 1724).

- ^ a b Friederichs, 2011, at 498.

- ^ 25 U.S.C. § 1725(b)(1).

- ^ 30 M.R.S.A. § 6204.

- ^ Robert T. Anderson, Bethany Berger, Philip P. Frickey & Sarah Krakoff, American Indian Law: Cases and Commentary, 253–321, 393–515, 629–707 (2d ed. 2010).

- ^ Whitney Austin Walstad, Maine v. Johnson: A Step in the Wrong Direction for the Tribal Sovereignty of the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the Penobscot Nation, 32 Am. Indian L. Rev. 487 (2007). See, e.g., Maine v. Johnson, 498 F.3d 37 (1st Cir. 2007) (holding that the EPA erred in exempting two tribally owned facilities from state permitting under the Clean Water Act and settlement acts); Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians v. Ryan, 484 F.3d 73 (1st Cir. 2007) (holding that the settlement acts abrogated tribal sovereign immunity and applied state employment discrimination laws to the tribes); Aroostook Band of Micmacs v. Ryan, 484 F.3d 41 (1st Cir. 2007) (same); Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Maine, 75 F.3d 784 (1st Cir. 1996) (holding that the settlement act prevents the application of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act to Maine).

- ^ See, e.g., Penobscot Nation v. Fellencer, 164 F.3d 706 (1st Cir. 1999) (holding that the termination of tribal employees is an "internal tribal matter"); Akins v. Penobscot Nation, 130 F.3d 482 (1st Cir. 1997) (holding that stumpage permits are an "internal tribal matter").

- ^ Narragansett Tribe of Indians v. S. R.I. Land Dev. Co. (Narragansett I), 418 F. Supp. 798, 802 (D.R.I. 1976).

- ^ Narragansett I, 418 F. Supp. at 804.

- ^ Narragansett, 418 F. Supp. at 808.

- ^ Mashpee Tribe v. New Seabury Corp., 592 F.2d 575 (1st Cir. 1979). aff'g, 427 F. Supp. 899 (D. Mass. 1977).

- ^ Mashpee, 592 F.2d at 582.

- ^ Mashpee, 592 F.2d at 586 n.6.

- ^ Mashpee Tribe v. Secretary of Interior, 820 F.2d 480, 482 (1st Cir. 1987) (Breyer, J.); Epps v. Andrus, 611 F. 2d 915, 918 (1st Cir. 1979).

- ^ Mashpee, 592 F.2d at 581.

- ^ 25 C.F.R. § 83.7. The BIA's authority to promulgate these regulations derived from 25 U.S.C. § 9.

- ^ Golden Hill Paugussett Tribe of Indians v. Weicker, 39 F.3d 51 (2nd Cir. 1994).

- ^ Golden Hill Paugussett, 39 F.3d at 60–61. See also United States v. 43.47 Acres of Land, 45 F. Supp. 2d 187, 191–94 (D. Conn. 1999).

- ^ Golden Hill Paugussett Tribe of Indians v. Rell, 463 F. Supp. 2d 192 (D. Conn. 2006).

- ^ Paterson & Roseman, 1979, at 118–151.

- ^ Paterson & Roseman, 1979, at 152.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 294 n.12.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 271.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 287.

- ^ Kempers, 1989, at 267–68.

References

- Paul Brodeur, Annals of Law: Restitution, The New Yorker, Oct. 11, 1982, at 76.

- Kim Isaac Eisler, Revenge of the Pequots: How a Small Native American Tribe Created the World's Most Profitable Casino 63–81 (2002).

- Nicole Friederichs, A Reason to Revisit Maine's Indian Claims Settlement Acts: The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 35 Am. Indian L. Rev. 497 (2011).

- Margot Kempers, There's Losing and Winning: Ironies of the Maine Indian Land Claim, 13 Legal Stud. F. 267 (1989).

- Dean J. Kotlowski, Out of the Woods: The Making of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, 30 Am. Indian Culture & Res. J. 63 (2006).

- John M.R. Paterson & David Roseman, A Reexamination of Passamaquoddy v. Morton, 31 Me. L. Rev. 115 (1979).

External links

- Text of the First Circuit decision at Google Scholar