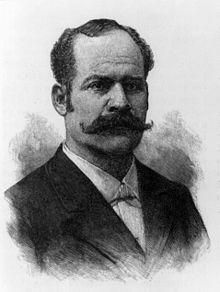

José Santos Zelaya

Template:Distinguish2 Template:Spanish name

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2008) |

José Santos Zelaya | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Nicaragua | |

| In office 25 July 1893 – 21 December 1909 | |

| Vice President | Anastasio J. Ortiz 1893–1894 Francisco Baca 1894–1896 |

| Preceded by | Joaquín Zavala |

| Succeeded by | José Madriz |

| Personal details | |

| Born | José Santos Zelaya López 1 November 1853 Managua |

| Died | 17 May 1919 New York City |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

José Santos Zelaya López (1 November 1853 Managua – 17 May 1919 New York City) was the President of Nicaragua from 25 July 1893 to 21 December 1909.

Early life

He was a son of José María Zelaya Irigoyen, born in Nicaragua, and his mistress Juana López Ramírez. His father José María was married to Rosario Fernández.

Politics

Zelaya was of Nicaragua's liberal party and enacted a number of progressive programs, including improving public education, building railroads, and establishing steam ship lines and enacting constitutional rights that provided for equal rights, property guarantees, habeas corpus, compulsory vote, compulsory education, the protection of arts and industry, minority representation, and the separation of state powers.[1] However, his wish for national sovereignty often led him to policies contrary to colonialist interests.

In 1894, he took control of the Mosquito Coast by military force; it had long been the subject of dispute, home to a native kingdom claimed as a protectorate by the British Empire. Zelaya's fortitude paid off, and the United Kingdom, not wishing to go to war for this distant land of little value to the Empire, recognized Nicaraguan sovereignty over the area.

Reelection, possibility of a canal, and response from the US

José Santos Zelaya was reelected president in 1902 and again in 1906.

The possibility of building a canal across the isthmus of Central America had been the topic of serious discussion since the 1820s, and Nicaragua was long a favored location. When the United States shifted its interests to Panama, Zelaya negotiated with Germany (who happened to be in the middle of a cold war with the U.S over Caribbean ports) and Japan in an unsuccessful effort to have a canal constructed in his state. Fearful that president Zelaya might generate an alternative foreign alignment in the region, the U.S. labeled him a tyrant in opposition to U.S. planned hegemony.[citation needed]

José Zelaya had ambitions of reuniting the Federal Republic of Central America, with, he hoped, himself as national president. With this aim in mind, he gave aid to liberal federalist factions in other Central American nations. This threatened to create a full scale Central American war which would endanger the United States Panamanian canal and give European nations, such as Germany, an excuse to intervene to protect the collection of their bank's payments in the region or if failing that then demand a land concession.

The Zelaya administration had growing friction with the United States government, for example while the French government had inquired to the U.S. whether a loan to Nicaragua would be deemed unfriendly, the U.S. secretary of state required the loan to be conditional on U.S. relations. After the loan was pending on the Paris stock exchange, the U.S. further isolated Nicaragua by claiming any money Zelaya would receive "would be without doubt spent to purchase munitions to oppress his neighbors" and in "hostility to peace and progress in Central America." The US State Department also demanded that all investments in Central America would also need be approved by the U.S. as a means to protect U.S. interests and to overthrow president Zelaya according to a French minister.[2]

The U.S. started giving aid to his Conservative and Liberal opponents in Nicaragua who broke out in open rebellion in October 1909, led by Liberal General Juan J. Estrada. Nicaragua sent its forces into Costa Rica to suppress Estrada's pro U.S. destabilizing forces, but U.S. officials deemed the incursion as an affront to Estrada's aims and attempted to coerce Costa Rica into acting first against Nicaragua, but Foreign Minister Ricardo Fernández Guardia assured Calvo that Costa Rica was determined "not to enter such dangerous actions as those proposed by Washington." It "considered the joint action proposed contrary to the Washington treaty and desired to maintain a neutral attitude."[3] Costa Rican officials considered the United States a more serious threat to Central American peace and harmony than Zelaya's Nicaragua. Costa Rica Foreign Minister Fernández Guardia insisted, "We do not understand here what interests can the Washington government have that Costa Rica assumes a resolutely aggressive position against Nicaragua, with the danger of compromising the observation of the...conventions of December 20, 1907.... It is in Central America's interest that U.S. action with respect to Nicaragua should assume the character of an international conflict and in no sense the character of an intervention tolerated and even less solicited or supported by the other signatory republics of the Washington Treaty.[4]

US sets up base of operations in Nicaragua

Officers of Zelaya's government executed some captured rebels; two United States mercenaries were among them, and the U.S. government declared their execution grounds for a diplomatic break between the countries which later led to formal intervention. At the start of December, United States Marines landed in Nicaragua's Bluefields port, supposedly to create a neutral zone to protect foreign lives and property but which also acted as a base of operations for the anti-Zelayan rebels. On 17 December 1909, Zelaya turned over power to José Madriz and fled to Spain. Madriz called for continued struggle against the mercenaries, but in August 1910 diplomat Thomas Dawson obtained the withdrawal of Madriz. Thereafter the U.S. called for a constituent assembly to write a constitution for Nicaragua and the vacant presidency was filled by a series of Conservative politicians including Adolfo Diaz. During this time, through free trade and loans, the U.S. exercised strong control over the country.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

Notes

- ^ José Santos Zelaya: President of Nicaragua, 5-18; Adán Selva, Lodo y ceniza de una politica que ha podrido las raices de la nacionalidad nicaragüense ( Managua, 1960), 48-49; Gregorio Selser, Nicaragua de Walker a Somoza ( Mexico, 1984), 82.

- ^ MAE to Jean Jules Jusserand, May 17, 24, June 4, 1909, Jusserand to MAE, May 22, July 1, 1909, Henry White to Pichon, May 28, 1909, Min. Finances to MAE, May 29, 1909, MAE to Min. Finances, July 2, 1909, CP 1918, Nic., Finances, Emprunts, N. S. 3, AMAE, Paris (copies in F 30 393 1: folder Nic., Amef); Tony Chauvin to MAE, July 28, 1909, Pierre Lefévre-Pontalis to MAE, July 30, Aug. 26, 1909, CP 1918, Hond., Finances, N. S. 3, AMAE, Paris (copies in F 30 393 1: folder Hond., Amef); Chauvin to Morgan, Harjes and Company, July 31, 1909, Chauvin to Min. Finances, Aug. 3, 1909, MAE to Min. Finances, Sept. 14, 1909, F 30 393 1: folder Hond., Amef.

- ^ Ricardo Fernández Guardia to Calvo, Nov. 23, 1909, MRE, libro copiador 170, AN, CR; Fernández Guardia to Calvo, Nov. 25, 1909, MRE, libro copiador 157, AN, CR; Munro, Intervention and Dollar Diplomacy, 173-74, presents the case for no U.S. involvement in the Estrada revolt; Challener, Admirals, Generals, and American Foreign Policy, 289-99, Healy, "The Mosquito Coast, 1894-1910," present the case for U.S. assistance to Estradai Lewis Einstein to Sec. St., Nov. 9, 1911, RG 59, Decimal files, 711.18/4, U.S. & CR (M 670/r 1). See also de Benito to MAE, Oct. 10, 1910, H1609, AMAE, Madrid.

- ^ Fernández Guardia to Calvo, Nov. 27, 1909, MRE, libro copiador 170, AN, CR; Calvo to Fernández Guardia, Nov. 28, 1909, MRE, caja 188, AN, CR; Munro, Intervention and Dollar Diplomacy, 206; Bailey, "Nicaragua Canal, 1902-1931,"6, 10.