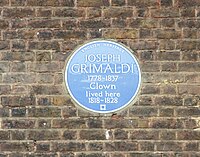

Joseph Grimaldi

Joseph Grimaldi (18 December 1778 – 31 May 1837) was an English actor, comedian and dancer, who became the most popular English entertainer of the Regency era.[1] In the early 1800s, he expanded the role of Clown in the harlequinade that formed part of British pantomimes, notably at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and the Sadler's Wells and Covent Garden theatres. He became so dominant on the London comic stage that the harlequinade role of Clown became known as "Joey", and both the nickname and Grimaldi's whiteface make-up design were, and still are, used by other types of clowns. Grimaldi originated catchphrases such as "Here we are again!", which continue to feature in modern pantomimes.

Born in London to an entertainer father, Grimaldi began to perform as a child, making his stage debut at Drury Lane in 1780. He became successful at the Sadler's Wells Theatre the following year; his first major role was as Little Clown in the pantomime The Triumph of Mirth; or, Harlequin's Wedding in 1781, in which he starred alongside his father. After a brief schooling, he appeared in various low-budget productions and became a sought-after child performer. He took leading parts in Valentine and Orson (1794) and The Talisman; or, Harlequin Made Happy (1796), the latter of which brought him wider recognition.

Towards the end of the 1790s, Grimaldi starred in a pantomime version of Robinson Crusoe, which confirmed his credentials as a key pantomime performer. Many productions followed, but his career at Drury Lane was becoming turbulent, and he left the theatre in 1806. In his new association with the Covent Garden theatre, he appeared at the end of the same year in Harlequin or Mother Goose, which included perhaps his best known portrayal of Clown. Grimaldi's residencies at Covent Garden and Sadler's Wells ran simultaneously, and he became known as London's leading Clown and comic entertainer, enjoying many successes at both theatres. His popularity in London led to a demand for him to appear in provincial theatres throughout England, where he commanded large fees.

Grimaldi's association with Sadler's Wells came to an end in 1820, chiefly as a result of his deteriorating relationship with the theatre's management. After numerous injuries over the years from his energetic clowning, his health was also declining rapidly, and he retired in 1823. He appeared occasionally on stage for a few years thereafter, but his performances were restricted by his worsening physical disabilities. In his last years, Grimaldi lived in relative obscurity and became a depressed, impoverished alcoholic. He outlived both his wife and his actor son, Joseph Samuel, dying at home in Islington in 1837, aged 58.

Biography

Family background and early years

Grimaldi was born in Clare Market, London, into a family of dancers and comic performers.[2][3] His great-grandfather, John Baptist Grimaldi, was a dentist by trade and an amateur performer, who in the 1730s moved from Italy to England. There he performed the role of Pantaloon opposite John Rich's Harlequin.[4] John Baptist's son, Grimaldi's paternal grandfather, Giovanni Battista Grimaldi, began performing at an early age and spent much of his career in Italy and France.[2] According to biographer Andrew McConnell Stott, Giovanni was held in the Paris Bastille as the result of a scandalous performance.[n 1] After his release, Giovanni moved to London in 1742,[5] where John Baptist introduced him to John Rich; Giovanni then defrauded Rich and fled to the continent, where he later died.[5]

Grimaldi's father, Joseph Giuseppe Grimaldi (c. 1713–1788), an actor and dancer (known professionally as Giuseppe or "the Signor"), also made his way to London in around 1760.[6][n 2] His first London appearance was at the King's Theatre. He was later engaged by David Garrick to play Pantaloon in pantomimes at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, earning high praise,[8] and eventually became the ballet master there.[2] Grimaldi's mother, Rebecca Brooker, was born in Holborn in 1764.[9][n 3] She was apprenticed to Giuseppe Grimaldi in 1773 as a dancer and public speaker, and she became his mistress shortly afterwards, even though she was under 14[10] and he was about 60.[11]

Grimaldi's father was a serial philanderer who had at least ten children with three different women. In 1778, he divided his time between two London addresses occupied by his mistresses, Brooker and Anne Perry. Both women gave birth that year, Perry to a daughter named Henrietta and Brooker to Joseph.[12] Although jubilant at the birth of his first son, Giuseppe Grimaldi spent little time with Brooker, living mostly with Perry, and probably maintaining other mistresses as well.[12] Brooker raised her son alone for the first few years in Clare Market, a slum area of west London.[13] In about 1780, Brooker gave birth to a second son, John Baptiste. Keen to set up an acting dynasty, Giuseppe left Perry and his daughter and moved with Brooker and his two sons to Little Russell Street, High Holborn.[n 4] Giuseppe, who often displayed eccentric and obsessive behaviour, was a strict disciplinarian and often beat his children for disobeying his orders.[14] A fascination with death consumed his later life; he would feign death in front of his children, so as to gauge their reactions, and he insisted on his eldest daughter, Mary, decapitating him after his death because of his fear of being buried alive, a task which earned her £5 extra in her inheritance.[15]

Early years at Sadler's Wells and Drury Lane

From the age of two, Grimaldi was taught to act the characters in the harlequinade by his father. Although he and his younger brother John Baptiste both displayed acting talent, Joseph was groomed for the London stage.[16] He made his stage debut at the Sadler's Wells Theatre in late 1780, when Giuseppe took him on stage for his "first bow and first tumble".[11] On 16 April 1781, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the manager of Drury Lane,[2] cast both Giuseppe and Grimaldi in the pantomime The Wizard of the Silver Rocks; or, Harlequin's Release.[16] Sheridan employed dozens of children, including Grimaldi, as extras at Drury Lane.[17]

On Boxing Day 1781, Grimaldi took the part of Little Clown in the pantomime The Triumph of Mirth; or, Harlequin's Wedding at Drury Lane.[16] It was a success for him personally, and the pantomime enjoyed an extended run until March 1782.[18] As a result of his performance, he received further work offers from the management and became an established juvenile performer at Drury Lane.[19] At the same time, he was a prolific performer at Sadler's Wells where he played a host of minor roles, including monkeys, imps, fairies and demons.[19] The Drury Lane season ran every year from September to late spring, with Sadler's Wells playing from 15 April to the second week in October.[20] Though the two theatres staged similar productions, they appealed to different audiences: Drury Lane to the wealthy classes of society and Sadler's Wells to the boisterous working class.[21][22] Although Grimaldi's stage career was flourishing, Giuseppe enrolled him at Mr Ford's Academy, a boarding school in Putney, which educated the children of theatrical performers.[23] Although Grimaldi struggled with reading and writing, he showed a talent for art, as evidenced by some of his drawings that survive in the Harvard Theatre Collection.[24]

Their success on the London stage allowed the Grimaldis to enjoy an affluent lifestyle in contrast to other working-class families living in Clare Market and Holborn.[25] By the age of six, Grimaldi was considered a prominent stage performer by the press, with one critic from the Gazetteer commenting that "the infant son of Grimaldi performs in an astonishing manner".[26] One evening, Grimaldi was playing the part of a monkey and was led onto the stage by his father, who had attached a chain to Grimaldi's waist.[27][n 5] Giuseppe swung his young son around his head "with the utmost velocity",[29] when the chain snapped, causing young Grimaldi to land in the orchestra pit.[30] From 1789 Grimaldi would appear alongside his siblings in an act entitled "The Three Young Grimaldis".[14]

Grimaldi's father suffered ill health for many years and died of dropsy in 1788.[2][31] As a result, at age 9, Grimaldi became the family's principal breadwinner. Sheridan paid him an above-average wage of £1 a week at Drury Lane,[32] and allowed his mother to work at Drury Lane as a dancer.[33] However, the proprietors of Sadler's Wells were less supportive, cutting Grimaldi's pay from 15 shillings to 3 shillings a week, at which level it remained for the next three years.[33] The loss of Giuseppe's income and Joseph's reduced summertime earnings meant the Grimaldis could no longer afford to keep the house in Holborn. They moved to the slum district of St. Giles, where they took lodgings with a furrier in Great Wild Street.[34] Grimaldi's brother, John Baptiste, illegally signed on as a cabin boy aboard a frigate in 1788, when he was nine, using a false identity. Grimaldi saw him only once more in his life.[35][n 6]

John Philip Kemble took over the producer's (director's) duties at Drury Lane later in 1788 when Sheridan was promoted to chief treasurer.[37] Sheridan often employed Grimaldi in minor roles in Kemble's productions and continued to allow him to work concurrently at Sadler's Wells.[32] Grimaldi took an interest in the design and construction of stage scenery and would often help to design sets.[34][38] His stage performances over the next two years did not garner him the kind of success he had experienced under the management of his father,[39] and the role of pre-eminent Clown in London productions soon fell to Jean-Baptiste Dubois, a versatile French acrobat, horseman, singer and strongman, with a formidable repertoire of comic tricks.[40] Grimaldi worked as Dubois' assistant, although in later life he denied that he had been the Frenchman's student.[41]

In 1791 the Drury Lane Theatre was demolished,[42] and Grimaldi was loaned to the Haymarket Theatre, where he appeared, briefly, in the opera Cymon, which starred the tenor Michael Kelly. On 21 April 1794, the new Drury Lane theatre opened, and Grimaldi, now 15 years old, resumed his place as one of the principal juvenile performers.[43] The same year, he played his first major part since his father's death; as the dwarf in Valentine and Orson. Two years later, at Sadler's Wells, he played the role of Hag Morad in the Thomas John Dibdin Christmas pantomime The Talisman; or, Harlequin Made Happy. The pantomime was a success, and Grimaldi received rave reviews.[44] The Drury Lane management were eager to capitalise on his success, and later that year he was cast in Lodoiska, a Parisian hit adapted for the London stage by Kemble.[n 7] Grimaldi played Camasin, a role that required the acrobatic and sword-fighting skills that he had learned as a child.[46] He won wider admiration as Pierrot in the 1796 Christmas pantomime of Robinson Crusoe at Drury Lane.[47]

Grimaldi met his future wife, Maria Hughes in 1796. The eldest daughter of the proprietor of the Sadler's Wells theatre, Richard Hughes,[48] Maria was introduced to Grimaldi by his mother, Rebecca Brooker, and a romance soon blossomed. They married on 11 May 1799[49] and moved to 37 Penton Street, Pentonville.[50] Later that year, Grimaldi appeared in a succession of shows including A Trip to Scarborough (as a countryman) and Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (as a maid). The roles he took in these productions were eccentric and usually reserved for low comedians. Despite this, he was praised for his characterisations and was deemed a player of legitimate adult roles at Drury Lane, which qualified him to become a member of the prestigious Drury Lane Theatrical Fund.[51][n 8]

Last years at Drury Lane

In 1798, Drury Lane suspended its tradition of staging an annual Christmas pantomime, which meant that Grimaldi had to seek work elsewhere during the festive period.[52] The following year, with the help of his father-in-law, he joined the company at Sadler's Wells, where he played roles in several Charles Dibdin plays. Grimaldi made a big impression, especially in Dibdin's Easter 1800 pantomime, Peter Wilkins: or Harlequin in the Flying World, based on Robert Paltock's 1751 novel.[53][54] For this elaborate production, which featured two Clowns (Dubois and Grimaldi), Dibdin introduced new costume designs. Clown's costume was "garishly colourful ... patterned with large diamonds and circles, and fringed with tassels and ruffs," instead of the tatty servant's outfit that had been used for a century. The production was a hit, and the new costume design was copied by others in London.[54] Despite Dubois' "endless bag of tricks [and] vast array of skills", his performance appeared artificial, in contrast to Grimaldi, who was better able to "draw the audience into believing the essential comedic qualities" of Clown.[55]

At Drury Lane later in 1800, he starred as an officer in The Wheel of Fortune by Richard Cumberland, a Jewish pedlar in The Indian, as Clown in Robinson Crusoe, and as the Second Gravedigger in Hamlet, alongside John Philip Kemble.[56][57] Grimaldi's wife Maria and his unborn child died during childbirth on 18 October 1800.[48] To cope with his grief, Grimaldi would often perform two shows a night; one at Sadler's Wells and the other at Drury Lane.[58]

With the Christmas season approaching, and the success of Peter Wilkins still a topic of conversation within theatrical circles, Kemble decided to stage the first Drury Lane pantomime in three years, Harlequin Amulet; or, The Magick of Mona, with Grimaldi as Punch and then as Clown, instead of Dubois.[59][60] In this production, Harlequin became "romantic and mercurial, instead of mischievous", leaving Grimaldi's Clown as the "undisputed agent" of chaos.[60] The pantomime was a great success, running for thirty-three performances and having a second Drury Lane season at Easter 1801; as a result, Grimaldi became recognised as one of London's leading Clowns.[61] Grimaldi originated the catchphrase "Here we are again!", which is still used in pantomime.[62][63] He also was known for the mischievous catchphrase "Shall I?", which prompted audience members to respond "Yes!"[64]

Grimaldi and Dubois appeared together again later that spring at Sadler's Wells in Dibdin's Harlequin Alchemist, which set up a mock duel between the two Clowns, with the audience deciding who could pull the most hideous face. Grimaldi consistently won.[60] In the next piece, Harlequin Benedick; or, The Ghost of Mother Shipton. Dubois was relegated to the role of Pierrot, while Grimaldi played Clown. Grimaldi's mother was in the cast, appearing as the Butcher's Wife. He then appeared in another Dibdin play, The Great Devil.[65] During the run, he accidentally injured himself on stage by shooting himself in the foot[66] and was confined to bed for five weeks.[67] His mother became so concerned at her son's fragile and still grief-stricken state that she employed a dancer at Drury Lane, Mary Bristow, to care for him full-time during those weeks. They formed a close friendship, which resulted in a loving relationship,[68] and they married on 24 December 1801.[69][70]

After a falling-out with Kemble at Drury Lane, Grimaldi was dismissed and began appearing at the nearby Covent Garden Theatre. He also took up an engagement at his father-in-law's theatre in Exeter.[71] There was no Christmas 1801 or Easter 1802 pantomime at Drury Lane, and Kemble noticed a reduction in his theatre's audiences.[72] Grimaldi began to appear in provincial theatres, with the first appearance being in Rochester, Kent, in 1801. In March 1802, he returned to Kent where he performed in pantomime, earning £300 for two days work. His dismissal from Drury Lane was short-lived, and he was reinstated within a few months[73] in a revival of Harlequin Amulet.[74]

Sadler's Wells closed for refurbishment at the end of its 1801 season and re-opened on 19 April 1802; Grimaldi returned to take a major role in the Easter pantomime, for which he designed the look of his recurring Clown character "Joey". He began by painting a white base over his face, neck and chest before adding red triangles on the cheeks, thick eyebrows and large red lips set in a mischievous grin. Grimaldi's design is used by many modern clowns. According to Grimaldi's biographer Andrew McConnell Stott, it was one of the most important theatrical designs of the 1800s.[75] Later in 1802, Dubois left the Sadler's Wells company, making Grimaldi the sole resident Clown.[76] Grimaldi starred in St. George, Champion of England opposite his friend Jack Bologna. This was followed by Ko and Zoa; or, the Belle Savage. A critic from The Times remarked that the pair's death scene together was "truely affecting" [sic].[77] Bologna and Grimaldi's on-stage partnership had by now become the most popular on the British stage; the Morning Chronicle thought they "stood unrivalled" compared to other acts within the harlequinade.[78]

On 21 November 1802, his wife Mary bore Grimaldi his only child, a son, Joseph Samuel, whom they called "JS".[48][79] Grimaldi introduced his young son to the eccentric atmosphere at both Drury Lane and Sadler's Wells from the age of 18 months.[80] Although eager to have his son follow him onto the stage, Grimaldi felt that it was more important for the boy to have an education and eventually enrolled him at Mr Ford's Academy.[n 9]

Grimaldi returned to Drury Lane late in 1802 and starred in a production of Bluebeard,[82] followed by the Christmas pantomime Love and Magic.[83] In 1803 Grimaldi's contract at Sadler's Wells was extended for another three years. He starred as Rufo the Robber in Red Riding Hood, as Sir John Bull in New Broom and Aminadab in Susanna Centlivre's A Bold Stroke for a Wife.[84][85] The Napoleonic Wars had started, and the new proprietors of Sadler's Wells and Drury Lane looked to Grimaldi to satisfy audiences eager for comic relief. Cinderella; or, the Little Glass Slipper was presented at Drury Lane on 3 January 1804. Grimaldi played the part of Pedro, a servant to Cinderella's sisters. The production was a major success for the theatre, enhanced by Michael Kelly's musical score;[86] however Grimaldi and the critics grew concerned that the theatre was underusing his talents and that he was miscast in the role.[87][88]

The Sadler's Wells season commenced at Easter 1805, and Grimaldi and Jack Bologna enjoyed a successful period. Drury Lane staged the opera Lodoiska, in which Grimaldi, his mother and his wife all had starring roles.[89] After this he was asked to choreograph John Tobin's play, The Honey Moon, at Drury Lane on short notice. He accepted on the proviso that his wages be increased for the show's entire run and not just until a new dancing instructor was found. The Drury Lane management agreed to pay Grimaldi £2 more per week.[90] A few weeks into his new assignment, management appointed James D'Egville as the new ballet master. D'Egville's debut production was Terpsichore's Return, in which Grimaldi played Pan, a role which he considered to be one of his best assignments to date.[91] That October, however, the theatre reduced his wages. The extra £2 that he had been promised had been deducted from his salary when Terpsichore closed, and he approached Thomas Dibdin for advice. Dibdin advised him to leave Drury Lane and to take up a residency at the nearby Covent Garden Theatre.[92] Grimaldi wrote to Thomas Harris, the manager of the Covent Garden Theatre, hoping to persuade him to stage Christmas pantomimes. Harris was already a supporter of the shows and had employed the writing talents of both Charles Dibdin and his co-writer Charles Farley.[93] Grimaldi met with Harris and obtained a contract.[94] Before joining that theatre, however, he had to satisfy prior commitments at Drury Lane, appearing in the poorly received Harlequin's Fireside.[89]

Covent Garden years

In 1806, Grimaldi bought a second home, a cottage in Finchley, to which he retired between seasons.[95][n 10] He was engaged to appear at Astley's Theatre in Dublin, in a play by Thomas Dibdin and his brother Charles. The Dibdins leased the theatre,[98] but it was badly in need of repair. As a result audiences were small, and the show's box-office takings suffered. Grimaldi donated his salary to help pay for the renovation of the theatre.[99] The Dibdin company, with Grimaldi, transferred to the nearby Crow Street Theatre where they performed a benefit concert in aid of Astley's. After two more plays, the company moved back to London.[100]

Harlequin and the Forty Virgins opened the Easter season at Sadler's Wells and lasted the entire season. Grimaldi sang "Me and my Neddy", which proved very successful for both him and the theatre. Amid great expectations, he appeared at the Covent Garden Theatre on 9 October 1806 playing Orson opposite Charles Farley's Valentine in Thomas Dibdin's Valentine and Orson.[101] Grimaldi, who considered the role of Orson to be the most physically and mentally demanding of his career, nevertheless performed the part with enthusiasm on tour in the provinces.[102]

Perhaps the best-known of Grimaldi's pantomimes was Thomas Dibdin's Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, The Golden Egg, which opened on 29 December 1806 at the Covent Garden Theatre.[32] As in most pantomimes, he played a dual role, in this case first as "Bugle", a wealthy but abrasive eccentric womaniser, and after the transformation to the harlequinade, as Clown.[103][n 11] Mother Goose was a runaway success with its London audiences and earned an extraordinary profit of £20,000. It completed a run of 111 performances over a two-year residency, a record for any London theatre production at the time.[106] Grimaldi, however, considered the performance to be one of the worst of his career and became depressed.[107][108] Critics thought differently, attributing the pantomime's success to Grimaldi's performance.[48] It prompted one critic from European Magazine to write: "We have not for several years witnessed a Pantomime more attractive than this: whether we consider the variety and ingenuity of the mechanical devices [or] the whim, humour, and agility of the Harlequin, Clown and Pantaloon".[109] Kemble stated that Grimaldi had "proved himself [as] the great master of his art",[110] while the actress Mrs Jordan called him "a genius ... yet unapproached".[111] The production regularly played to packed audiences.[112]

In September 1808, a fire at the Covent Garden theatre destroyed much of the Mother Goose scenery; the production transferred to the Haymarket Theatre where it completed its run. While Kemble and Harris raised funds and renovated Covent Garden, Grimaldi made provincial appearances in Manchester and Liverpool. The Covent Garden theatre re-opened in December 1809 with a revival of Mother Goose.[113] In an attempt to recover the costs incurred by the rebuilding, Kemble raised the theatre's seat prices, causing audiences to protest violently for more than two months, and the management was forced to reinstate the old prices.[114] Grimaldi's 1809–10 productions included Don Juan, in which he appeared as Scaramouche, and Castles in the Air, as Clown.[115] Later in 1810, he appeared in Birmingham in a benefit performance in aid of his sister-in-law.[116] The following year, Grimaldi sang "Tippitywitchet" for the first time at Sadler's Wells in Charles Dibdin's pantomime Bang up, or, Harlequin Prime; it became one of his most popular songs.[2][n 12]

By 1812, despite Grimaldi's success as a performer, he was close to bankruptcy as a result of his wife's extravagant spending, a number of thefts by his accountant and the cost of maintaining both an idyllic country lifestyle and his son JS's private education.[118] The strain on Grimaldi's finances caused him to accept as many provincial engagements as he could. That year, he travelled to Cheltenham and appeared again as Scaramouche in a revival of Don Juan. In nearby Gloucester he met the poet Lord Byron, on whose poem the play was based, at a dinner party.[119] Byron was in awe at meeting the famous Clown, stating that he felt "great and unbounded satisfaction in becoming acquainted with a man of such rare and profound talents".[120] Grimaldi returned to London to star as Queen Ronabellyana with much success in the Covent Garden Christmas pantomime, Harlequin and the Red Dwarf; or, The Adamant Rock.[n 13] After this, he increasingly played "dame" roles.[104]

Sadler's Wells opened its season in April 1814 with Grimaldi appearing in, amongst others, Kaloc; or, The Pirate Slave.[122] That year he played the title role in Robinson Crusoe at Sadler's Wells, with his young son, JS, making his stage debut as Man Friday. Other pantomimes followed at Sadler's Wells that year, including The Talking Bird, in which he played Clown, and he also played Clown in productions at the Surrey Theatre and Covent Garden – a challenging schedule.[123] Later in 1814, he played the title role in a revival of Don Juan at Sadler's Wells, with JS in his second role as Scaramouche. The receipts at the box-office were unusually large and confirmed, in Grimaldi's mind, that his son was capable of sustaining his own career. Grimaldi suffered two setbacks towards the end of the year, becoming housebound for a few months due to illness[124] and learning of the death of his friend, mentor and former father-in-law, Richard Hughes, in December.[125] In early 1815, Grimaldi and his son played father and son Clowns in Harlequin and Fortunio; or, Shing-Moo and Thun-Ton.[126][n 14]

During 1815, the relationship between Grimaldi and Thomas Dibdin became strained. Dibdin, as manager at Sadler's Wells, denied Grimaldi's request for a month's leave to tour the provincial theatres. Dibdin was annoyed at the tolerant attitude Grimaldi displayed in his position as the Chief Judge and Treasurer of the Sadler's Wells Court of Rectitude, a body set up to regulate the behaviour of performers.[127][n 15] Grimaldi briefly left Sadler's Wells in 1815 to conduct a tour of the northern provincial theatres. Alongside Jack Bologna, he staged fifty-six shows during the summer months and earned £1,743, a much higher amount than he earned at Sadler's Wells.[128] Dibdin was struggling, and after the tour Grimaldi used the problems at Sadler's Wells to negotiate a lucrative contract. Dibdin agreed to a salary increase but bristled at Grimaldi's other demands and eventually gave the position of resident Clown to the little-known Signor Paulo.[129]

Later career

In 1815, Grimaldi played Clown in Harlequin and the Sylph of the Oak; or, The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green at Covent Garden, followed by the Christmas pantomime Robinson Crusoe; or, The Bold Buccaneer, in which he played Friday to Charles Farley's title character.[130] Grimaldi conducted a remunerative but gruelling tour to Scotland, Manchester and Liverpool in 1818. He sustained bruising and strains from two falls, the second of which left him briefly unable to walk.[131] He and Mary moved to 56 Exmouth Market, Islington,[132] where he recovered from his injuries before going on tour with his son.[133]

At Easter 1819, in The Talking Bird, or, Perizade Columbine,[2] he introduced perhaps his best known song "Hot Codlins", an audience participation song about a seller of roasted apples who gets drunk on gin while working the streets of London.[134][n 16] Songs about trades were popular on the stage in the 1800s. Grimaldi sought inspiration for the character of the apple seller by walking around the streets of London and observing real-life tradespeople.[138]

Despite Signor Paulo's success at Sadler's Wells, Richard Hughes's widow Lucy, who was a majority shareholder at the theatre, pleaded with Grimaldi to return. He agreed on the conditions that he was sold an eighth share in the theatre, remained the resident Clown and received a salary of 12 guineas a week. She agreed to his terms, and he took the part of Grimaldicat in the 1818 Easter pantomime The Marquis De Carabas; or, Puss in Boots. The show was a disaster and closed after one night. Grimaldi was booed off the stage after an impromptu joke (eating a prop mouse) upset the audience and caused two female audience members to fight in the auditorium.[139] The audience was also angry at Grimaldi's weak performance; later he felt that this marked the beginning of his career's decline.[140] Dibdin left Sadler's Wells that year; his fortunes changed rapidly for the worse, and he spent time in a debtors' prison. Grimaldi's debut as a theatre proprietor was also a failure. Although Jack Bologna, Mary, JS and Bologna's wife Louisa were all cast in Grimaldi's only commissioned pantomime, The Fates; or, Harlequin's Holy Day, he had underestimated the amount of work required to run a theatre, and the strain of management hastened the already rapid deterioration in his health.[141]

The shares in Sadler's Wells were sold, with Grimaldi's going to Daniel Egerton. Egerton wanted to keep Grimaldi on the payroll but proposed loaning him to other theatres. Grimaldi refused a contract on these terms and instead appeared alongside JS in a few engagements in Ireland.[142] During the Easter season of 1820, Grimaldi appeared at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in Harlequin and Cinderella; or, the Little Glass Slipper. Grimaldi played the wife of the lead character Baron Pomposini; the role was probably an early example of a pantomime dame.[143] In the latter months of 1820, Grimaldi's health worsened, and he suffered frequent emotional breakdowns, gastric spasms, breathlessness and severe rheumatoid pain.[144] These ailments did not affect his desire to perform. That September he appeared at Covent Garden, as Kasrac in Aladdin followed by the Christmas pantomime Harlequin and Friar Bacon; the pantomime was particularly successful.[145]

In May 1821, Grimaldi collapsed after a performance of Undine; or, the Spirit of the Waters. Doctors diagnosed him as suffering from "premature old age".[14] JS took over his father's role and completed the remainder of the show's run. Now acting as an official understudy,[124] JS filled many of his father's other theatrical engagements, including a rerun of Harlequin and Mother Bunch; or, the Yellow Dwarf, in which he caused a scandal by threatening and verbally abusing a heckler in the audience.[146][n 17] In the early 1820s, Grimaldi made a brief recovery and held a six-week engagement at the Coburg Theatre where he appeared as Clown in Salmagundi; or, the Clown's Dish of All Sorts; a pantomime which ran for a week before being replaced by Disputes in China; or, Harlequin and the Hong Merchants. Both productions were successful, but Grimaldi was taken ill half way through the latter's run.[148]

In 1822, Grimaldi travelled to Cheltenham, in poor health, to fulfil an engagement as Clown by another actor in Harlequin and the Ogress; or, the Sleeping Beauty in the Wood. Despite the rehearsals being cut short due to Grimaldi's rapidly deteriorating health, critics praised his performances.[149][n 18]

Last years and death

Grimaldi retired from the stage in 1823 as a result of ill health. The years of extreme physical exertion his clowning had involved had taken a toll on his joints, and he suffered from a respiratory condition that often left him breathless.[150] The Times noted in 1813:

Grimaldi is the most assiduous of all imaginable buffoons and it is absolutely surprising that any human head or hide can resist the rough trials he volunteers. Serious tumbles from serious heights, innumerable kicks, and incessant beatings come on him as matters of common occurrence, and leave him every night fresh and free for the next night's flagellation.[151]

Although officially retired, Grimaldi still received half of his former small salary from Drury Lane until 1824. Soon after the fee stopped, Grimaldi fell into poverty after a number of ill-conceived business ventures and because he had entrusted management of his provincial earnings to people who cheated him.[152] Despite his disabilities, he offered his services as a cameo performer in Christmas pantomimes. Along with Bologna, he re-appeared briefly at Sadler's Wells where he gave some acting instruction to the mime artist William Payne, the future father of the Payne Brothers.[153] He also started working for Richard Brinsley Peake, namesake of Richard Brinsley Sheridan,[154] who was the dramaturge at the English Opera House. Peake hired Grimaldi to star in Monkey Island alongside his son JS. However, Grimaldi's health deteriorated further and he was forced to quit before the show opened; his scene was cut.[155] The early end to his career, worries about money, and the uncertainty over his son's future made him increasingly depressed.[48] To make light of it, he would often joke about his condition: "I make you laugh at night but am Grim-all-day".[156] In 1828, two "farewell" benefit performances were held for him. In the first, he appeared as Hock the German soldier and a drunken sailor in Thomas Dibdin's melodrama The Sixes; or, The Fiends at Sadler's Wells to an audience of 2,000 people.[157] Unable to stand for long periods of time, he sang a duet with JS and finished the evening with a scene from Mother Goose.[158] His last farewell benefit performance on 27 June 1828 was at Drury Lane.[159] Between 1828 and 1836, Grimaldi relied on charity benefits to replace his lost income.[160]

The relationship between Grimaldi and his son first became strained during the early 1820s.[161] JS, who had made a career of emulating his father's act, received favourable notices as Clown, but his success was constantly overshadowed by that of his father. He became resentful of his father and publicly shunned any association with him. JS became an alcoholic and was increasingly unreliable.[162] In 1823, he became estranged from his parents, who saw their son only occasionally over the next four years, as JS went out of his way to avoid them.[161] They communicated only through letters, with Grimaldi often sending his son notes begging for money. JS once replied: "At present I am in difficulties; but as long as I have a shilling you shall have half". However, there is no record of him ever sending money to his father.[163] JS finally returned home in 1827, when the Grimaldis were awakened one night to discover their son standing in the street, feverish, emaciated and dishevelled.[164]

After appearing in a few Christmas pantomimes and benefits for his father, JS fell into unemployment and was incarcerated in a debtors' prison for a time; his alcoholism also further worsened.[165] In 1832, Grimaldi, Mary and their son moved to Woolwich,[166] but JS often abused his parents' hospitality by bringing home prostitutes and fighting in the house with his alcoholic friends.[167] He moved out later that year and died at his lodgings on 11 December 1832, aged 30.[168][169] With Grimaldi almost crippled, and Mary having suffered a stroke days before JS's death, they made a suicide pact. They took some poison, but the only result was a long bout of stomach cramps. Dismayed at their failure, they abandoned the idea of suicide.[170]

Mary died in 1834, and Grimaldi moved to 33 Southampton Street, Islington,[170] where he spent the last few years of his life alone as a depressed alcoholic.[171] On 31 May 1837 he complained of a tightening of the chest but recuperated enough to attend his local public house, The Marquis of Cornwallis, where he spent a convivial evening entertaining fellow patrons and drinking to excess.[171][172] He returned home that evening and was found dead in bed by his housekeeper the following morning.[173][174] The coroner recorded that he had "died by the visitation of God".[175] Grimaldi was buried in St. James's Churchyard, Pentonville, on 5 June 1837.[176] The burial site and the area around it was later named Joseph Grimaldi Park.[177]

Legacy and reputation

After Grimaldi's death, Charles Dickens was invited by Richard Bentley to edit and improve Thomas Egerton Wilks's clumsily written life of Grimaldi, which had been based on the clown's own notes. As a child, Dickens saw Grimaldi perform at the Star Theatre, Rochester, in 1820.[178] The Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi sold well, to Dickens's surprise.[179][n 19]

Grimaldi's fame was established primarily by his numerous successes as Clown in pantomimes. His Clown satirised many aspects of contemporary British life, and made comic mockery of absurdities in fashion. Grimaldi quickly became the most famous Clown in London, gradually transforming the Clown character from a pratfalling country bumpkin into the most important character in the harlequinade, more important even than Harlequin. He expanded the role of Clown to include a range of comic impersonations, from the rival suitor, to household cook or nurse. Grimaldi's popularity changed the balance of the evening's entertainment, so that the first, relatively serious, section of the pantomime soon dwindled to "little more than a pretext for determining the characters who were to be transformed into those of the harlequinade." He became so dominant in the harlequinade that later Clowns were known as "Joey", and the term, as well as his make-up design, were later generalised to other types of clowns.[2][104]

A contributor to Bentley's Miscellany wrote in 1846: "To those who never saw him, description is fruitless; to those who have, no praise comes up to their appreciation of him. We therefore shake our heads and say 'Ah! You should have seen Grimaldi!'"[181] Another writer commented that his performances elevated his role by "acute observation upon the foibles and absurdities of society. ... He is the finest practical satyrist that ever existed. ... He was so extravagantly natural, that [no one was] ashamed to laugh till tears coursed down their cheeks at Joe and his comicalities."[182] The British dramatist James Planché worried, in a rhymed couplet, that Grimaldi's death meant the end of a genre: "Pantomime's best days are fled; Grimaldi, Barnes, Bologna dead!"[183]

Grimaldi became "easily the most popular English entertainer of his day".[1] The Victoria and Albert Museum and the actor Simon Callow have both concluded that no other Clown achieved Grimaldi's level of fame.[64][184] Richard Findlater, author of a 1955 Grimaldi biography, commented: "Here is Joey the Clown, the first of 10,000 Joeys who took their name from him; here is the genius of English fun, in the holiday splendour of his reign at Sadler's Wells and Covent Garden ... during his lifetime [Grimaldi] was generally acclaimed as the funniest and best-loved man in the British theatre."[185] A later biographer, Andrew McConnell Stott, wrote that "Joey had been the first great experiment in comic persona, and by shifting the emphasis of clowning from tricks and pratfalls to characterisation, satire and a full sense of personhood, he had established himself as the spiritual father of all those later comedians whose humour stems first and foremost from a strong sense of identity."[186]

Grimaldi is remembered today in an annual memorial service on the first Sunday in February at Holy Trinity Church in Hackney. The service, which has been held since the 1940s, attracts hundreds of clown performers from all over the world who attend the service in full clown costume.[187][188] In 2010 a coffin-shaped musical memorial dedicated to Grimaldi, made of musical floor tiles, was installed in Joseph Grimaldi Park. The bronze tiles are tuned so that when danced upon it is possible to play "Hot Codlins".[189]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ No records exist of Giovanni's transgression.

- ^ Giuseppe was born sometime between 1710 and 1716 in either France or Genoa. Giuseppe's mother was Catherine Grimaldi, a dancer, who died in 1773.[7]

- ^ Rebecca's father, Zachariah Brooker, was a butcher who kept an abattoir in Bloomsbury. He encouraged Rebecca's career and secured for her minor roles in various London theatres.[10]

- ^ McConnell Stott believes that Giuseppe fathered a third son with Brooker, named William, in about 1786. William Grimaldi, Joseph Grimaldi and a daughter from another relationship, Catherine, all performed together in a Christmas pantomime in 1789, appearing as "the three young Grimaldis".[14]

- ^ A child acting the part of an animal during a performance was known as "Skining" or "Skinwork". This was predominantly a male part, while girls often played fairies or trees.[28]

- ^ John Baptiste visited Joseph one night in 1804 at Drury Lane. Joseph was midway through a performance. He finished the play and returned to his dressing room to find that John had again disappeared. John was never seen again. His family believed that he had been murdered that night as a result of a robbery, although officials from the Royal Navy suggested that he may have been press-ganged.[36]

- ^ The music was taken from separate operas of the same name by Rodolphe Kreutzer and Luigi Cherubini with additions by Stephen Storace.[45]

- ^ Acts such as dancers and buffoons were excluded from joining. Grimaldi was one of the few pantomimists allowed into the membership.[52]

- ^ JS excelled at school. After Ford's Academy, he attended a private school in Pentonville.[81]

- ^ The cottage was demolished in 1908 to make way for the Finchley Memorial Hospital.[96][97]

- ^ The first four scenes of the play were centred around a search for Mother Goose and the golden egg by characters who parodied contemporary figures. When the golden egg was found, the characters transformed into those of the harlequinade, which consisted of fifteen scenes, and a grand finale. Music underscored the whole piece, and there was no spoken dialogue.[104] The performances were often flamboyant and hugely energetic, styles in which Grimaldi had become fluent.[105]

- ^ The song's full title was "A Typitywitchet, or, Pantomimical Paroxysms",[2] and he also sang it in Don Juan the following year.[117]

- ^ Other productions in 1813 included the comic burletta Poor Vulcan, in February 1813, followed by Aladdin, in which he played the Chinese Slave. Grimaldi's benefit show in early July featured three comic plays: Five Miles Off, Love, Law and Physic, and a rerun of Harlequin and the Red Dwarf. The Drury Lane management granted permission for Robinson Crusoe and his Man Friday to be performed at Covent Garden at the close of this season in July.[121] Covent Garden re-opened in September, and Harlequin and the Swans; or, the Bath of Beauty was the 1813 Christmas pantomime, which ran until April the following year. Sadak and Kalasrade then took over, with Grimaldi appearing as Hasan the Slave.[122]

- ^ Harlequin and Fortunio; or, Shing-Moo and Thun-Ton was the first known pantomime to feature an early variation of what would become the principal boy role, played as a breeches role by Maria de Camp. The principal boy role would not become a regular pantomime part for another 40 to 50 years.[126]

- ^ Theatre rules were adopted nationwide and were often enforced vigorously. At Sadler's Wells, drunkenness, swearing, arguing, stealing clothes from the dressing rooms and breaking wind were all forbidden. Performers were not allowed to converse with each other off stage, and female performers were not allowed to take encores.[127]

- ^ "Hot Codlins" was composed by John Whitaker[135] with lyrics by Charles Dibdin.[136] Grimaldi would sing a verse: "A little old woman, her living got by selling codlins, hot, hot, hot; ... tho' her codlins were hot, she felt herself cold. So to keep herself warm, she thought it no sin to fetch for herself a quartern of ..."[134][137] The audience shouted back the last word, "gin" with glee, and Grimaldi would scold them in a shocked tone: "Oh! For Shame!".[104] Then the audience joined in the refrain: "ri tol iddy, iddy, iddy, ri tol iddy, iddy, rI tol lay."[136] "Hot Codlins" is still sung by Clowns, often to open performances of plays and pantomimes.[134]

- ^ JS's desire to distinguish himself from his famous father had intensified during their frequent tours of provincial theatres. His verbal abuse of the heckler may have been an attempt to establish a persona much removed from the respectable reputation of his father.[147]

- ^ The Cheltenham Spa was famous for its supposedly curative powers. Grimaldi factored this into his decision to take the engagement in ill health; he regularly drank the water during his visit and between performances.[149]

- ^ John Forster quotes an unpublished letter in which Dickens responds to the accusation that he must not have seen Grimaldi in person: "Now, Sir, although I was brought up from remote country parts in the dark ages of 1819 and 1820 to behold the splendour of Christmas pantomimes and the humour of Joe, in whose honour I am informed I clapped my hands with great precocity, and although I even saw him act in the remote times of 1823 ... I am willing ... to concede that I had not arrived at man's estate when Grimaldi left the stage".[179] When Dickens arrived in America for the first time in 1842, he stayed at the Tremont House, America's "pioneer first-class hotel". Dickens "bounded into the Tremont's foyer shouting out 'Here we are!', Grimaldi's famous catch-phrase and as such entirely appropriate for a great and cherished entertainer making his entrance upon a new stage."[63] Later, Dickens was known to imitate Grimaldi's clowning on several occasions.[180]

References

- ^ a b Byrne, Eugene. "The patient", Historyextra.com, 13 April 2012

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Moody, Jane. "Grimaldi, Joseph", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 13 February 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ "Scraps from New Books and Periodicals", Sheffield Independent, 8 February 1879, p. 10

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 9

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, pp. 7–9

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 10

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 10 and 12

- ^ Arundell, p. 31

- ^ Findlater, p. 15

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, p. 19

- ^ a b Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 6

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, p. 20

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 21

- ^ a b c d McConnell Stott, p. 22

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 56

- ^ a b c McConnell Stott, p. 28

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 45–46

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 30

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, p. 31

- ^ Findlater, p. 18

- ^ Findlater, pp. 14–17

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 38–39

- ^ Findlater, p. 20

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 48

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 42

- ^ "Son of Signor – Top Drury Lane Draw", Gazetteer, 10 April 1794, p. 18

- ^ Findlater, p. 21

- ^ Findlater, p. 22

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 37

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 47

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 53

- ^ a b c Neville, p. 6

- ^ a b Findlater, p. 41

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, p. 58

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 58–59

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 127–29

- ^ Findlater, pp. 53–56

- ^ Findlater, p. 46

- ^ Findlater, p. 51

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 64

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 68

- ^ Thomson, p. 310

- ^ Findlater, p. 56

- ^ Findlater, pp. 59–60

- ^ Girdham, Jane. Lodoiska in New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Stanley Sadie (ed.) 1992, pp. 1303–04

- ^ Findlater, p. 69

- ^ Findlater, p. 60

- ^ a b c d e Neville, p. 7

- ^ Findlater, p. 67

- ^ Thornbury, p. 280

- ^ Findlater, pp. 68–69

- ^ a b Findlater, p. 68

- ^ Neville, pp. 6–7

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, pp. 95–100

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 99

- ^ Findlater, p. 76

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 101

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 88

- ^ Findlater, pp. 80–81

- ^ a b c McConnell Stott, p. 109

- ^ Findlater, pp. 82–83

- ^ Partridge, p. 188

- ^ a b Slater, p. 178

- ^ a b "Grimaldi the Clown", Victoria and Albert Museum website, accessed 10 September 2012

- ^ Findlater, p. 85

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 90

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 91

- ^ Neville, p. 28

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 106–07

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, Saint Pancras Parish Church, Register of marriages, P90/PAN1, Item 055

- ^ Findlater, p. 84

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 94

- ^ Findlater, pp. 83–88

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 113

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 117–18

- ^ Findlater, pp. 89–90

- ^ "Truely affecting", The Times, 21 August 1802, p. 6

- ^ "Mr Grimaldi and Mr Bologna at Easter", Morning Chronicle, 31 August 1802, p. 11

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 153

- ^ Findlater, pp. 123–24

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 246

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 121

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 123

- ^ Findlater, p. 92

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 97

- ^ Findlater, pp. 94–95

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 144

- ^ Findlater, p. 95

- ^ a b Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 114

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 115

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 116

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), pp. 117–19

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 144–45

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 146

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 154

- ^ "Finchley, Friern Barnet and Totteridge", London Borough of Barnet Council, accessed 20 June 2012

- ^ "Near here at Fallow Corner stood the home of Joseph Grimaldi actor and famous clown (1779–1837)", Open Plaques.org, accessed 20 June 2012

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 119

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), pp. 119–20

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 122

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 126

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 127

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 171–73

- ^ a b c d Ellacott, Nigel and Peter Robbins. "Joseph Grimaldi", Its-behind-you.com, 2002, accessed 9 December 2012

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 174

- ^ Mayer, p. 16

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 129

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 200

- ^ "We Have Not for Several Years", European Magazine, vol. 51, January 1807, p. 54

- ^ Boaden, p. 500

- ^ Boaden, p. 201

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 199–200

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 203

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 206–07

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 209

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 211

- ^ Neville, p. 59

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 230

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), pp. 178–79

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 180

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), pp. 184–85

- ^ a b Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 186

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), pp. 188–89

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, p. 254

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 187

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, p. 247

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, pp. 236–37

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 248

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 238–39

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 193

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 242–43

- ^ Grimaldi, Joseph (1778–1837), English Heritage, accessed 20 June 2012

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 245

- ^ a b c Findlater, p. 139

- ^ Sadler's Wells Introduction, Islington Borough Council, accessed 22 September 2012

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, p. 389

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 251

- ^ Anthony, p. 101

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 249–50

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 250

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 251–52

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 253

- ^ "The origin of popular pantomime stories", Victoria and Albert Museum website, accessed 10 February 2013

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 252

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), pp. 254–55

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 255

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 256

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 257–60

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, pp. 264–65

- ^ "Death of Grimaldi", Westmorland Gazette, 10 June 1837, p. 4

- ^ The Times, January 5, 1813, p. 3, Issue 8802

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 230–31

- ^ Boase, G. C. Payne, William Henry Schofield (1803–1878)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 29 November 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ Stephens, John Russell. "Peake, Richard Brinsley (1792–1847)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 28 April 2011

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 272–273

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), p. 13

- ^ Findlater, p. 195

- ^ Findlater, pp. 195–96

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), pp. 231–33

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 294 and 309

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, p. 274

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 122

- ^ Dickens, Memoirs, p. 266, quoted in McConnell Stott, p. 278

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 280

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 293, 295 and 298

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 298–99

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 273–74

- ^ Grimaldi (Boz edition), pp. 250–51

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 303

- ^ a b McConnell Stott, pp. 307–08

- ^ a b Neville, p. 63

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 309–12

- ^ "Coroner's Inquest on Joseph Grimaldi The Celebrated Clown", Morning Post, 3 June 1837, p. 4

- ^ "The Tragic Life of Grimaldi", The Age, 17 June 1959, p. 22

- ^ "Coroner's Inquest On Joseph Grimaldi", London Standard, 3 June 1837, p. 3

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 312

- ^ Joseph Grimaldi Park, Islington Borough Council, accessed 3 June 2012

- ^ Charles Dickens: Collected Papers, Vol 1, Preface to Grimaldi, p. 9

- ^ a b Forster, p. 65

- ^ Dolby, pp. 39–40

- ^ "You Should have seen Grimaldi", Bentley's Miscellany, Issue 19, 24 May 1846, pp. 160–61

- ^ Broadbent, chapter 16

- ^ Planché, p. 27

- ^ Callow, Simon. "The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi: Laughter, Madness and the Story of Britain's Greatest Comedian by Andrew McConnell Stott", The Guardian, 19 December 2009, accessed 11 December 2012

- ^ Findlater, p. 9

- ^ McConnell Stott, p. 320

- ^ "Remembering the Sad Clown Joseph Grimaldi", Camden New Journal, accessed 16 August 2012

- ^ Boult, Adam. "Juggling for Jesus", The Guardian, 13 February 2010, accessed 2 December 2012

- ^ "Joseph Grimaldi Park", London Gardens Online, accessed 26 January 2014.

Sources

- Anthony, Barry (2010). The King's Jester. London: I. B. Taurus & Co. ISBN 978-1-84885-430-7.

- Arundell, Dennis (1978). The Story of Sadler's Wells, 1683–1964. Newton Abbott: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-7620-1.

- Boaden, James (1825). Memoirs of the Life of John Philip Kemble. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. OCLC 0405082762.

- Broadbent, R. J. (1901). A History of Pantomime. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co.

- Boz (Charles Dickens) (1853). Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. London: G Routledge & Co.

- Dolby, George (1887). Charles Dickens as I Knew Him: The Story of the Reading Tours in Great Britain and America (1866–1870). London: C. Scribner's & Sons. ISBN 978-1-108-03979-6.

- Findlater, Richard (1955). Grimaldi King of Clowns. London: Magibbon & Kee. OCLC 558202542.

- Forster, John (2010). The Life of Charles Dickens (1872–1874). London: Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-147-55282-9.

- McConnell Stott, Andrew (2009). The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi. Edinburgh: Canongate Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84767-761-7.

- Mayer, David (1969). Harlequin In His Element: The English Pantomime, 1806–1836. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-37275-1.

- Neville, Giles (1980). Incidents In the Life of Joseph Grimaldi. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd. ISBN 0-224-01869-8.

- Partridge, Eric (2005). A Dictionary of Catchphrases: British and American from the sixteenth century to the present day. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05916-9.

- Planché, James (1847). The New Planet; Or, Harlequin Out of Place: An Extravaganza, in One Act. London: S. G. Fairbrother. OCLC 9180307.

- Slater, Michael (2009). Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11207-8.

- Thomson, Peter (1995). The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, 1660–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43437-9.

- Thornbury, Walter (1887–1893). Old And New London Volume 2. London: Cassell & Co Ltd. OCLC 35291703.

External links

- Grimaldi the Clown at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

- Grimaldi Blue Plaque on the English Heritage website.

- The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi by Andrew McConnell Stott review by Jenny Uglow, taken from the Guardian, 1 November 2009.

- The Life of Joseph Grimaldi; with Anecdotes of his Contemporaries by Henry Downes Miles, 1838.

- Joseph Grimaldi Satirical Drawings at the British Museum.

- Joseph Grimaldi at The Public Domain Review.