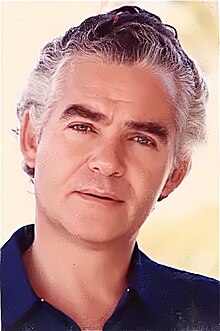

Jules Irving

Jules Irving (né Julius Israel, in New York City, April 13, 1925 - Reno, Nevada, July 28, 1979) was an American actor, director, educator, and producer, who in the 1950s co-founded the San Francisco Actor's Workshop. When the Actor's Workshop closed in 1966, Irving moved to New York City and became the first Producing Director of the Repertory Company of the Vivian Beaumont Theater of Lincoln Center.

In 1955, the Actor's Workshop was the first West Coast theater to sign an Equity "Off-Broadway" contract. Irving had started the Workshop with fellow New Yorker Herbert Blau, whom he knew from undergraduate days at New York University and then during graduate study at Stanford University.[1] The men were both professors at San Francisco State, Irving in the Drama department and Blau in English.

Known to friends as "Buddy," Irving was from childhood deeply involved in theater, supported in this by his family along with his older brother Richard, despite a degree of religious reservation inculcated by bizarre bearded Russian/Yiddish-speaking rabbinical teachers that dis-inspired what Irving called a "lost generation" of the children of Jewish immigrants.[2] He was active in school shows and made his Broadway debut at the age of thirteen in George S. Kaufman's The American Way. He joined the army in 1943, serving in the infantry during the Battle of the Bulge and as a Russian translator when his unit met Soviet forces. After V-E Day, he transferred to Special Services and had the opportunity to hone his theater managerial skills as he organized camp shows under Joshua Logan.[3]

San Francisco Actor's Workshop, 1952-1966

From its inception on January 16, 1952 in a loft above a judo academy on Divisadero Street in San Francisco to its formal demise in 1966, the Actor's Workshop set new standards as a pioneer of resident professional art theater in the United States.[4]

Among those present in 1952 for a "study group" or "workshop" were Irving, Blau, their wives, Priscilla Pointer and Beatrice Manley; Hal J. Todd, who had been at Stanford with Irving and Blau; Richard Glyer, an instructor at San Francisco State University; Paul Cox, an aspiring playwright; and S. F. State student Dan Whiteside.[5] Irving was "managing director"; he shared artistic leadership with Blau (who was "consulting director," but had not yet directed a show). Irving guided the theater's finances and led primary day-by-day operations of the company's growth to its Elgin Street playhouse and then to offices on Folsom Street and two year-round theaters, the Encore and the Marines' Memorial. A major transition occurred in 1956 when the Workshop was evicted from Elgin Street to make room for a new freeway. The company had an option to renew its lease on the Marines' Memorial Theater but no money. Enter a young Canadian, Alan Mandell, who as volunteer Business Manager (and de facto chief executive with Irving) helped inaugurate the first subscription season for the Actor's Workshop.[6]

Irving and Blau were insistent idealists who developed the Workshop in the tradition of the Group Theatre of the 1930s; they and key company members were dedicated to principles of social responsibility and ensemble artistry.[7] The troupe's repertoire focused initially on Miller and other modern American writers, such as Odets, O'Neill, and Tennessee Williams, but soon expanded to the contemporary world dramas of Samuel Beckett, Brecht, Genet, John Osborne, Yukio Mishima, and Harold Pinter.[8]

Respected as an actor as well as director, Irving played major roles, including Proctor in The Crucible [9] and Happy in Death of a Salesman [10] (which he also directed) in the Workshop's productions of Arthur Miller plays. When the Workshop produced the west coast premiere of Beckett's Waiting for Godot, Irving was the loquacious servant, Lucky.[11] The production played to the Workshop's regular audiences, then performed for inmates at San Quentin prison [12][13][14][15] and on to the 1958 Brussels World's Fair where it represented American theater under the aegis of the US State Department.

The travel to Brussels was not without incident. This was the era of the "Second Red Scare," when America was going through a reactionary review of its image and institutions, and the Workshop found itself caught for a time between the State Department's initial enthusiasm for sponsoring Godot and a pause when some officials questioned whether this absurdist play of Irish/French origin could truly represent America. Irving was informed that the Workshop would need to fund its own travel to get to Belgium. After weeks of fund-raising and while the company was still in New York, he received word that it would be “inadvisable” for a named stage manager to travel on to Brussels.[16] The opaque State Department left Irving and Blau to speculate while officials would not go on record (this was that time) that perhaps some liberal activity had brought negative attention down on the respected company member. The Workshop protested this extra-legal pressure, but in the end, feeling a responsibility to San Franciscans who had provided travel funds, proceeded to Brussels without the stage manager.[17]

In addition to his acclaimed abilities as the director of such Workshop productions as The Entertainer, Misalliance, The Glass Menagerie, and The Caretaker, Irving proved his skills as a financial manager over many years, shrewdly learning "by necessity," according to San Francisco writer Mark Harris, "a hundred-and-one uses for the pennies of a dollar."[18] In the world of theatrical idealism, chary vigilance is absolutely necessary, as the economics of the performing arts in our time require deficit funding to a greater degree every year.[19] Irving always had to struggle to keep the Workshop solvent. In doing so, he protected the company's artistic independence. He was thus extremely cautious in the late '50s when the Ford Foundation offered its hand.[20]

Some scholars note that Irving's life offers a study in artistic morality[21][22] although the "message" of any particular ethical exchange (Workshop v. State Department, Workshop v. Ford, v. Lincoln Center, v. ACT?) may remain unclear. A secular Jew,[23] Irving was honored with the Methodist-oriented Danforth Fellowship early in his professorial career for interests and achievements in "religion and higher education." [24] He was not a political person, but an active idealist, a man who sought in many ways, mostly through the theater, to improve the world.

In 1957, Irving began interacting with the Ford Foundation. At that time, the Foundation's Humanities and Arts Program offered grants-in-aid to “creative and performing artists,” etc.,[25] and the Workshop stood to benefit. Over time Irving developed a relationship with the Foundation as a consultant who advised fledgling theaters on survival and growth throughout the nation. Of particular note is his travel to Mississippi in the early '60s to work as an advisor to the Free Southern Theater,[26] a racially integrated troupe presenting Waiting for Godot amid a "beligerant, racist" atmosphere.[27] It is Irving's relationship with the Ford Foundation that also offers important lessons in the ethics and effects of philanthropic intervention in non-profit enterprises within a free market system. Readers interested in such effects-- in the advantages and trade-offs that may occur, the demands that arise among fellow non-included artists, and the ability of a young organization to adapt to powerful new circumstances-- are advised to study the Workshop, especially the years from 1958 on.[28]

Lincoln Center, 1965-72

The Workshop and its directors rose in national prominence for thirteen years until, in 1965, Irving and Blau were appointed to the artistic leadership at the Repertory Company in the Vivian Beaumont Theater of Lincoln Center. Several key actors were invited to accompany them to New York to form the nucleus of a repertory troupe. The direction of the Actor's Workshop was assumed by Kenneth Kitch and John Hancock,[29] who managed to keep the company going,[30] despite dwindling audiences, through the summer of 1966 when the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce rejected an appeal for aid from the company. The Chamber instead offered a financial incentive to William Ball's American Conservatory Theater to become the city's resident company.[31]

Irving and Blau were back in their home city.[32] After a rocky reception to their initial efforts, particularly to Blau's production of Danton's Death, [33] Blau resigned, but Irving was retained by the Lincoln Center board.[34] He steadily built the repertory company for the next seven years, concentrating mainly on his responsibilities and leadership as producer after personally directing some of the strongest early productions, including the powerful 1966 Caucasian Chalk Circle.[35][36][37]

While nurturing the acting and directing corps, he embraced at times certain "star" productions of quality, such as Mike Nichols' celebrated revival of Lillian Hellman's The Little Foxes and Gordon Davidson's staging of In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Irving understood that in New York no cultural institution may function well in isolation, so he reached out even to commercial productions of poetic and idealistic themes, e.g., Brian Friel's Lovers.[38] He ended his regime at Lincoln Center in 1972 with Ellis Rabb's widely celebrated direction of Maxim Gorky's Enemies[39] with a cast that included several actors who had come with Irving years earlier from San Francisco.[40]

Irving concluded a little over three decades in live theater when he left Lincoln Center. His was a remarkable career by any standard, not overlooking, as his widow Priscilla Pointer notes, his unflagging care and attention to raising their family of three children. He and his family moved to Southern California where Ms. Pointer, long a major actress with the Actor's Workshop and Lincoln Center, found opportunity to flourish in film roles, and where their daughter Amy Irving, who began her acting career at age nine on the Workshop stage, would carry on the family name. Irving produced television revivals of classic films, including Dark Victory and directed Loose Change and the celebrated series, Rich Man, Poor Man. As producer of the Lincoln Center original, he is credited for Masterpiece Theater's televised version of Enemies[41][42]

He died of a heart attack in 1979 on a vacation trip to Reno, Nevada, aged 54.[43]

References

- ^ Fowler, Keith, A History of the San Francisco Actor’s Workshop, 1969, Yale Drama Library | Series I. Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism Doctoral Dissertations | http://drs.library.yale.edu:8083/HLTransformer/HLTransServlet?stylename=yul.ead2002.xhtml.xsl&pid=arts:dra.0027&query=&clear-stylesheet-cache=yes&hlon=yes&big=&adv=&filter=&hitPageStart=&sortFields=&view=c01_1#s1

- ^ Noted in a typewritten essay, “Profile: The Talented Professor,” by S.F. State student Margaret Wood, based on interviews with Irving, n.d. [c.1950], in the papers of Jules Irving at Lincoln Center

- ^ Fowler, 23

- ^ Fowler, 820

- ^ Fowler, 13

- ^ Fowler, 205ff.

- ^ Fowler, 160

- ^ Fowler, see play lists in chapter headings

- ^ Hagan, R.H., “Powerful New Drama Enacted With Rare Skill,” S.F. Chronicle, December 8, 1954

- ^ Blau, Herbert, “A Play for Americans,” program note for Death of a Salesman, February 26, 1954

- ^ Blau, “Who is Godot?,” program for Waiting for Godot, February 28, 1957

- ^ The Workshop visit had a lasting effect. San Quentin inmates formed a drama club, and Alan Mandell became the group's advisor. In its final season, the Workshop presented a play by ex-inmate Rick Cluchey, The Cage, at the Encore. It toured to New York and elsewhere later.

SEE Kaltenheuser, Skip, "The Prison Playwright," Gadfly OnLine, Sep./Oct. 1999 - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (1958-08-06). "Theatre - 'Godot' for Fair - Coast Troupe Here on Way to Brussels - Article - NYTimes.com". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ^ Atkinson, Brooks, “Theater: ‘Godot’ For Fair,” New York Times, August 6, 1958.

- ^ Gleason, Gene, “‘Waiting For Godot’ . . . At the York,” N.Y. Herald Tribune, August 6, 1958

- ^ Fowler, 273

- ^ Priscilla Pointer replaced the stage manager for the performances at the Fair. Word quickly spread to the media, and The San Francisco Examiner ran a banner headline on September 15, 1958, "U.S.Ban On S.F. Theater Man," and all other local dailies ran prominent front page stories. See Fowler, ch. XL,259, for detail on "L'Affaire Godot."

- ^ Harris, Mark, "Blau & Irving Come Out of the West," NY Times, 02/21/1965,http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FB0814FD345B1B728DDDA80A94DA405B858AF1D3

- ^ http://www.sc.edu/uscpress/books/2010/3907x.pdf

- ^ Fowler, Ch XIII, 342

- ^ Kaufman, Stanley: http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=2283

- ^ Stage Left: "ACTFinds its Home in San Francisco," http://stageleft-movie.com/tag/jules-irving/

- ^ Fowler,17: "Following his Bar Mitzvah, Irving ceased all formal practice of his religion and became, through this default, a member of what he terms 'the lost generation of American Jews' i.e., young Jews unable to believe in the relevance of Judaism’s arcane and ancient rites to modern American life."

- ^ https://www.stlbeacon.org/#!/content/15834/danforth_foundation_has_ended_its_giving

- ^ Fowler, 341

- ^ "Free Southern Theater (1963-1978)". Amistad Research Center. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ^ Fowler, 750

- ^ See Fowler, especially chapters XIII (p. 342) through XXI (p. 684)

- ^ Fowler, chapter XXIV, including interviews with Kitch

- ^ Knickerbocker, Paine, “What is Heartbreaking Is That It Came So Close to Success,” S.F. Chronicle (“Datebook” section), July 31, 1966.

- ^ Knickerbocker, “The City is Offered a Repertory Theater,” S.F. Chronicle, July 29, 1966.

- ^ Pace, Eric, New York Times, "Jules Irving, Director of Lincoln Center Theater, Dead," July 31, 1979 http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70810FF385D12728DDDA80B94DF405B898BF1D3&scp=6&sq=Lincoln%20Center%20eric%20pace&st=cse

- ^ Fowler, 797ff

- ^ Fowler, 800

- ^ http://www.lct.org/content/lctreview/50%20Years%20215%20Productions.pdf

- ^ http://www.ibdb.com/production.php?id=3135

- ^ With Elizabeth Huddle as Grusha. A note from Yale doctoral historian Keith Fowler's diary: "This hearty, colorful production may have appeared in its finest light at the Sunday matinee on April 10--Easter in 1966-- when, as the Singer, the magnificent Brock Peters led us into Scene Two by gesturing a wide welcome and ringing out, 'On Easter Sunday morning!'"

- ^ Kerr, Walter, N. Y. Times, Nov. 12, 1972: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F7091EFD385E127A93C0A8178AD95F468785F9

- ^ Barnes, Clive, "The Theater: Rising to the Occasion," N. Y. Times, Nov. 10, 1972: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F50610F63A591A7493C2A8178AD95F468785F9

- ^ Including Robert Symonds as Zakhar Bardin; Robert Phalen, Alan Mandell, Daniel Sullivan, and Ray Fry

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0207452/

- ^ Pace, E., 07/31/79

- ^ Pace