Kahlil Gibran

Kahlil Gibran | |

|---|---|

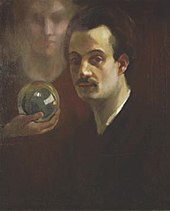

Kahlil Gibran, April 1913 | |

| Born | Jubran Khalil Jubran January 6, 1883 Bsharri, Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, Ottoman Syria |

| Died | April 10, 1931 (aged 48) New York City, United States |

| Occupation | Poet, painter, writer, philosopher, theologian, visual artist |

| Nationality | Lebanese and American |

| Genre | Poetry, parable, short story |

| Literary movement | Mahjar, New York Pen League |

| Notable works | The Prophet, Broken Wings |

Kahlil Gibran (/dʒɪˈbrɑːn/;[1] Full Arabic name Gibran Khalil Gibran, sometimes spelled Khalil;[a] Arabic: جبران خليل جبران / ALA-LC: Jubrān Khalīl Jubrān or Jibrān Khalīl Jibrān) (January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931) was a Lebanese-American artist, poet, and writer of the New York Pen League.

Gibran was born in the town of Bsharri[7] in the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, Ottoman Empire (north of modern-day Lebanon), to Khalil Gibran and Kamila Gibran (Rahmeh). As a young man Gibran immigrated with his family to the United States, where he studied art and began his literary career, writing in both English and Arabic. In the Arab world, Gibran is regarded as a literary and political rebel. His romantic style was at the heart of a renaissance in modern Arabic literature, especially prose poetry, breaking away from the classical school. In Lebanon, he is still celebrated as a literary hero.[8]

He is chiefly known in the English-speaking world for his 1923 book The Prophet, an early example of inspirational fiction including a series of philosophical essays written in poetic English prose. The book sold well despite a cool critical reception, gaining popularity in the 1930s and again especially in the 1960s counterculture.[8][9] Gibran is the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Laozi.[9]

Life

Early years

Gibran was born into a Maronite Catholic family from the historical town of Bsharri in northern Mount Lebanon, then a semi-autonomous part of the Ottoman Empire.[10] His mother, Kamila, daughter of a priest, was thirty when he was born; his father, Khalil, was her third husband.[11][12] As a result of his family's poverty, Gibran received no formal schooling during his youth in Lebanon.[13] However, priests visited him regularly and taught him about the Bible and the Arabic language (Lebanese Arabic).

Gibran's father initially worked in an apothecary, but with gambling debts he was unable to pay, he went to work for a local Ottoman-appointed administrator.[14][15] Around 1891, extensive complaints by angry subjects led to the administrator being removed and his staff being investigated.[16] Gibran's father was imprisoned for embezzlement,[9] and his family's property was confiscated by the authorities. Kamila Gibran decided to follow her brother to the United States. Although Gibran's father was released in 1894, Kamila remained resolved and left for New York on June 25, 1895, taking Khalil, his younger sisters Mariana and Sultana, and his elder half-brother Peter (in Arabic, Butrus).[14]

The Gibrans settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second-largest Syrian-Lebanese-American community[17] in the United States. Due to a mistake at school, he was registered as "Kahlil Gibran".[2] His mother began working as a seamstress[16] peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door to door. Gibran started school on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at Denison House, a nearby settlement house. Through his teachers there, he was introduced to the avant-garde Boston artist, photographer, and publisher Fred Holland Day,[9] who encouraged and supported Gibran in his creative endeavors. A publisher used some of Gibran's drawings for book covers in 1898.

Gibran's mother, along with his elder brother Peter, wanted him to absorb more of his own heritage rather than just the Western aesthetic culture he was attracted to.[16] Thus, at the age of fifteen, Gibran returned to his homeland to study at a Maronite-run preparatory school and higher-education institute in Beirut, called "al-Hikma" (The Wisdom). He started a student literary magazine with a classmate and was elected "college poet". He stayed there for several years before returning to Boston in 1902, coming through Ellis Island (a second time) on May 10.[18] Two weeks before he returned to Boston, his sister Sultana died of tuberculosis at the age of 14. The year after, Peter died of the same disease and his mother died of cancer. His sister Mariana supported Gibran and herself by working at a dressmaker's shop.[9]

Debuts, growing fame, and personal life

Gibran was an accomplished artist, especially in drawing and watercolor, having attended the Académie Julian [19]art school in Paris from 1908 to 1910, pursuing a symbolist and romantic style over the then up-and-coming realism.[citation needed] Gibran held his first art exhibition of his drawings in 1904 in Boston, at Day's studio.[9] During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Elizabeth Haskell, a respected headmistress ten years his senior. The two formed an important friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran's life. The nature of their romantic relationship remains obscure; while some biographers assert the two were lovers[20] but never married because Haskell's family objected,[8] other evidence suggests that their relationship never was physically consummated.[9] Haskell later married another man, but then she continued to support Gibran financially and to use her influence to advance his career.[21] She became his editor, and introduced him to Charlotte Teller, a journalist, and Emilie Michel (Micheline), a French teacher, who accepted to pose for him as a model and became close friends.[22] In 1908, Gibran went to study art in Paris for two years. While there he met his art study partner and lifelong friend Youssef Howayek.[23] While most of Gibran's early writings were in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. His first book for the publishing company Alfred A. Knopf, in 1918, was The Madman, a slim volume of aphorisms and parables written in biblical cadence somewhere between poetry and prose. Gibran also took part in the New York Pen League, also known as the "immigrant poets" (al-mahjar), alongside important Lebanese-American authors such as Ameen Rihani, Elia Abu Madi, and Mikhail Naimy, a close friend and distinguished master of Arabic literature, whose descendants Gibran declared to be his own children, and whose nephew, Samir, is a godson of Gibran's.

Death

-

Kahlil Gibran memorial in Washington, D.C.

-

Kahlil Gibran memorial in Boston, Massachusetts.

Gibran died in New York City on April 10, 1931, at the age of 48. The causes were cirrhosis of the liver and tuberculosis. Gibran expressed the wish that he be buried in Lebanon. This wish was fulfilled in 1932, when Mary Haskell and his sister Mariana purchased the Mar Sarkis Monastery in Lebanon, which has since become the Gibran Museum. Written next to Gibran's grave are the words "a word I want to see written on my grave: I am alive like you, and I am standing beside you. Close your eyes and look around, you will see me in front of you."[24]

Gibran willed the contents of his studio to Mary Haskell. There she discovered her letters to him spanning twenty-three years. She initially agreed to burn them because of their intimacy, but recognizing their historical value she saved them. She gave them, along with his letters to her which she had also saved, to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library before she died in 1964. Excerpts of the over six hundred letters were published in "Beloved Prophet" in 1972.

Mary Haskell Minis (she wed Jacob Florance Minis in 1923) donated her personal collection of nearly one hundred original works of art by Gibran to the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia in 1950. Haskell had been thinking of placing her collection at the Telfair as early as 1914. In a letter to Gibran, she wrote "I am thinking of other museums ... the unique little Telfair Gallery in Savannah, Ga., that Gari Melchers chooses pictures for. There when I was a visiting child, form burst upon my astonished little soul." Haskell's gift to the Telfair is the largest public collection of Gibran's visual art in the country, consisting of five oils and numerous works on paper rendered in the artist's lyrical style, which reflects the influence of symbolism. The future American royalties to his books were willed to his hometown of Bsharri, to be "used for good causes".

Writings

Style and recurring themes

Gibran was a great admirer of poet and writer Francis Marrash,[25][26] whose works he had studied at al-Hikma school in Beirut.[27] According to orientalist Shmuel Moreh, Gibran's own works echo Marrash's style, many of his ideas, and at times even the structure of some of his works;[28] Suheil Bushrui and Joe Jenkins have mentioned Marrash's concept of universal love, in particular, in having left a "profound impression" on Gibran.[27] The poetry of Gibran often uses formal language and spiritual terms; as one of his poems reveals: "But let there be spaces in your togetherness and let the winds of the heavens dance between you. Love one another but make not a bond of love: let it rather be a moving sea between the shores of your souls." [29]

Many of Gibran's writings deal with Christianity, especially on the topic of spiritual love. But his mysticism is a convergence of several different influences: Christianity, Islam, Judaism and theosophy. He wrote: "You are my brother and I love you. I love you when you prostrate yourself in your mosque, and kneel in your church and pray in your synagogue. You and I are sons of one faith—the Spirit."[30]

Reception and influence

Gibran's best-known work is The Prophet, a book composed of twenty-six poetic essays. Its popularity grew markedly during the 1960s with the American counterculture and then with the flowering of the New Age movements. It has remained popular with these and with the wider population to this day. Since it was first published in 1923, The Prophet has never been out of print. Having been translated into more than forty languages,[31] it was one of the bestselling books of the twentieth century in the United States.

Elvis Presley was deeply affected by Gibran's The Prophet after receiving his first copy in 1956. He reportedly read passages to his mother and over the years gave away copies of "The Prophet" to friends and colleagues. Photographs of his handwritten notes under certain passages throughout his copy are archived on various Museum websites. One of his most notable lines of poetry is from "Sand and Foam" (1926), which reads: "Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you". This line was used by John Lennon and placed, though in a slightly altered form, into the song "Julia" from The Beatles' 1968 album The Beatles (aka "The White Album").[32] Johnny Cash recorded Gibran's "The Eye of the Prophet" as an audio cassette book, and Cash can be heard talking about Gibran's work on a track called "Book Review" on Unearthed. David Bowie mentions Gibran in the song "The Width Of a Circle" from Bowie's 1970 album The Man Who Sold the World. Bowie used Gibran as a "hip reference",[33] because Gibran's work "A Tear and a Smile" became popular in the hippy counterculture of the 1960s. In 2016 Gibran's fable On Death was composed in Hebrew by Gilad Hochman to the unique setting of soprano, theorbo and percussion and premiered in France under the title River of Silence.[34]

Visual art

His more than seven hundred images include portraits of his friends WB Yeats, Carl Jung and Auguste Rodin.[8] A possible Gibran painting was the subject of a September 2008 episode of the PBS TV series History Detectives. His drawings collected by Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha.

Religious views

Gibran was born into a Maronite Christian family and raised in Maronite schools. He was influenced not only by his own religion but also by Islam, and especially by the mysticism of the Sufis. His knowledge of Lebanon's bloody history, with its destructive factional struggles, strengthened his belief in the fundamental unity of religions, which his parents exemplified by welcoming people of various religions in their home.[27] Themes of influence in his work were Islamic/Arabic art, European Classicism and Romanticism (William Blake and Auguste Rodin,) pre-Raphelite Brotherhood, and more modern symbolism and surrealism.[35] Major personal influences on Gibran include Fred Holland Day, Josephine Preston Peabody[36] who called Gibran himself a "prophet", and Mary Haskell who was his patron. Gibran also worked with St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery on a number of occasions[37] both in terms of art like his drawings and readings of his work,[38][39] and in religious matters.[40]

Gibran had a number of strong connections to the Bahá'í Faith. One of Gibran's acquaintances later in life, Juliet Thompson, reported several anecdotes relating to Gibran. She recalled Gibran had met 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the leader of the religion at the time of his visit to the United States, circa 1911[14]–1912.[41] Gibran was unable to sleep the night before meeting him in person to draw his portrait.[27][42] Thompson reported Gibran later saying that all the way through writing Jesus, the Son of Man, he thought of `Abdu'l-Bahá. Years later, after the death of `Abdu'l-Bahá, Gibran gave a talk on religion with Bahá'ís[40] and at another event with a viewing of a movie of `Abdu'l-Bahá, Gibran rose to talk and proclaimed in tears an exalted station of `Abdu'l-Bahá and left the event weeping.[41] A noted scholar on Gibran is Suheil Bushrui from Gibran's native Lebanon, also a Bahá'í,[43] published more than one volume about him[27][44] and served as the Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace at the University of Maryland[8][45] and winner of the Juliet Hollister Awards from the Temple of Understanding.[46]

Political thought

Gibran was by no means a politician. He used to say : "I am not a politician, nor do I wish to become one" and "Spare me the political events and power struggles, as the whole earth is my homeland and all men are my fellow countrymen."[47]

Nevertheless, Gibran called for the adoption of Arabic as a national language of Syria, considered from a geographic point of view, not as a political entity.[48] When Gibran met 'Abdu'l-Bahá in 1911–12, who traveled to the United States partly to promote peace, Gibran admired the teachings on peace but argued that "young nations like his own" be freed from Ottoman control.[14] Gibran also wrote the famous "Pity The Nation" poem during these years, posthumously published in The Garden of The Prophet.[49]

When the Ottomans were eventually driven out of Syria during World War I, Gibran sketched a euphoric drawing "Free Syria" which was then printed on the special edition cover of the Lebanese paper al-Sa'ih; and in a draft of a play, Gibran expressed his desire for Lebanese independence and progress.[50] This play, according to Khalil Hawi, "defines Gibran's belief in Syrian nationalism with great clarity, distinguishing it from both Lebanese and Arab nationalism, and showing us that nationalism lived in his mind, even at this late stage, side by side with internationalism."[51]

Works

In Arabic:

- Nubthah fi Fan Al-Musiqa (Music, 1905)

- Ara'is al-Muruj (Nymphs of the Valley, also translated as Spirit Brides and Brides of the Prairie, 1906)

- Al-Arwah al-Mutamarrida (Rebellious Spirits, 1908)

- Al-Ajniha al-Mutakassira (Broken Wings, 1912)

- Dam'a wa Ibtisama (A Tear and A Smile, 1914)

- Al-Mawakib (The Processions, 1919)

- Al-'Awāsif (The Tempests, 1920)

- Al-Bada'i' waal-Tara'if (The New and the Marvellous, 1923)

In English, prior to his death:

- The Madman (1918) (transcriptions: wikisource, gutenberg)

- Twenty Drawings (1919)

- The Forerunner (1920)

- The Prophet, (1923)

- Sand and Foam (1926)

- Kingdom of the Imagination (1927)

- Jesus, The Son of Man (1928)

- The Earth Gods (1931)

Posthumous, in English:

- The Wanderer (1932)

- The Garden of The Prophet (1933, completed by Barbara Young)

- Lazarus and his Beloved (Play, 1933)

Collections:

- Prose Poems (1934)

- Secrets of the Heart (1947)

- A Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1951)

- A Self-Portrait (1959)

- Thoughts and Meditations (1960)

- A Second Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1962)

- Spiritual Sayings (1962)

- Voice of the Master (1963)

- Mirrors of the Soul (1965)

- Between Night & Morn (1972)

- A Third Treasury of Kahlil Gibran (1975)

- The Storm (1994)

- The Beloved (1994)

- The Vision (1994)

- Eye of the Prophet (1995)

- The Treasured Writings of Kahlil Gibran (1995)

Other:

- Beloved Prophet, The love letters of Khalil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and her private journal (1972, edited by Virginia Hilu)

Memorials and honors

- Lebanese Ministry of Post and Telecommunications published a stamp in his honor in 1971.

- Gibran Museum in Bsharri, Lebanon

- Gibran Khalil Gibran Garden, Beirut, Lebanon

- Gibran Khalil Gibran collection, Museo Soumaya, Mexico.

- Kahlil Gibran Street, Montreal, Quebec, Canada inaugurated on September 27, 2008 on occasion of the 125th anniversary of his birth.

- Gibran Kahlil Gibran Skiing Piste, The Cedars Ski Resort, Lebanon

- Kahlil Gibran Memorial Garden in Washington, D.C.,[52] dedicated in 1990

- Elmaz Abinader, Children of Al-Mahjar: Arab American Literature Spans a Century[53]

- Gibran Memorial Plaque in Copley Square, Boston, Massachusetts see Kahlil Gibran (sculptor).

- Khalil Gibran International Academy, a public high school in Brooklyn, NY, opened in September 2007

- Kahlil Gibran, Bust, Yerevan, Armenia (2005)[54][55]

- Khalil Gibran School Rabat, Moroccan and British international school in Rabat, Morocco

- Pavilion K. Gibran at École Pasteur in Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- Khalil Gibran Park (Parcul Khalil Gibran) in Bucharest, Romania

- Gibran Kalil Gibran sculpture on a marble pedestal indoors at Arab Memorial building at Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil

- Gibran Khalil Gibran Memorial, in front of Plaza de las Naciones, Buenos Aires.

- Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Bust (see photo on right)

- Gibran Khalil Gibran Cultural Space in northern Caracas, Venezuela.

Notes

- ^ Due to a mistake at a school in the United States, he was registered as Kahlil Gibran, the spelling he used thenceforth.,[2] Other sources use Khalil Gibran, reflecting the typical English spelling of the forename Khalil. In academic contexts, his name is sometimes spelled Jubrān Khalīl Jubrān,[3][4] Jibrān Khalīl Jibrān,[3][5] or more rarely Jibrān Xalīl Jibrān.[6]

References

Citations

- ^ "Gibran". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ a b Gibran 1998: 29

- ^ a b Starkey, Paul (2006). Modern Arabic Literature. The New Edinburgh Islamic Surveys. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-7486-1291-2.

- ^ Allen, Roger (2000). An Introduction to Arabic Literature. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 255. ISBN 0-521-77230-3.

- ^ Badawi, M. M., ed. (1992). Modern Arabic Literature. The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-521-33197-5.

- ^ Cachia, Pierre (2002). Arabic Literature—An Overview. Culture and Civilization in the Middle East. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 189. ISBN 0-7007-1725-0.

- ^ Freeth, Becky (April 27, 2015). "Salma Hayek is sophisticated in florals as she visits Lebanon museum". Daily Mail Online.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b c d e Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet: Why is it so loved?, BBC News, May 12, 2012, Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Acocella, Joan (January 7, 2008). "Prophet Motive". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ Jagadisan, S."Called by Life", The Hindu, January 5, 2003, accessed July 11, 2007

- ^ "Khalil Gibran (1883–1931)", biography at Cornell University library on-line site, retrieved February 4, 2008

- ^ "Gibran - Birth and Childhood". leb.net.

- ^ "Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931)". Middle East & Islamic Studies. Cornell University Library. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Cole, Juan. "Chronology of his Life". Juan Cole's Khalil Gibran Page – Writings, Paintings, Hotlinks, New Translations. Professor Juan R.I. Cole. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Walbridge, John. "Gibran, his Aesthetic, and his Moral Universe". Juan Cole's Kahlil Gibran Page – Writings, Paintings, Hotlinks, New Translations. Professor Juan R.I. Cole. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c Mcharek, Sana (March 3, 2006). "Khalil Gibran and other Arab American Prophets" (PDF). approved thesis. Florida State University. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Khalil Gibran". Cornell University Library.

- ^ "Passenger Record". Records of Ellis Island. The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Robin Waterfield, Prophet: The Life and Times of Kahlil Gibran

- ^ Salem Otto, Annie, The Love letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell, Houston, 1964

- ^ Alexandre Najjar, Kahlil Gibran, a biography, Saqi, 2008, chapter 7 (p.79), "Beloved Mary"

- ^ Najjar, op.cit, p.59

- ^ Yusuf Huwayyik, Gibran in Paris, New York : Popular Library, 1976

- ^ Waterfield, Robin (1998). Prophet: The Life and Times of Kahlil Gibran. St. Martin's Press. pp. 281–282.

- ^ Moreh, Shmuel (1976). Modern Arabic Poetry 1800–1970: the Development of its Forms and Themes under the Influence of Western Literature. Brill. p. 45. ISBN 978-9004047952.

- ^ Jayyusi, Salma Khadra (1977). Trends and Movements in Modern Arabic Poetry. Volume I. Brill. p. 23. ISBN 978-9004049208.

- ^ a b c d e Bushrui, Suheil B.; Jenkins, Joe (1998). Kahlil Gibran, Man and Poet: a New Biography. Oneworld Publications. p. 55. ISBN 978-1851682676.

- ^ Moreh, Shmuel (1988). Studies in Modern Arabic Prose and Poetry. Brill. p. 95. ISBN 978-9004083592.

- ^ "But let there be spaces in... at BrainyQuote". Brainyquote.com. April 10, 1931. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ Alexandre Najjar, Kahlil Gibran, a biography, Saqi, 2008, p.150

- ^ "Alwehar.com". Alhewar.com. December 3, 1995. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ "BBC World Service: The Man Behind the Prophet". Bbc.co.uk. May 7, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ "Pushing Ahead of the Dame". Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ "River of Silence". YouTube. April 10, 2016.

- ^ Curriculum Guide For the Film, Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, by Journeys in Film, 2015

- ^ "Peabody, Josephine Preston, 1874-1922". Harvard.

- ^ Kimberly Nichols (April 16, 2013). "The Brothers Guthrie: Pagan Christianity of the Early 20th Century". Newtopia Magazine. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ "The Rev. Dr. William Norman Guthrie…". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. October 24, 1931. p. 11. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ "St. Mark's-in-the-Bouwerie…". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. November 8, 1919. p. 16. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "Do we need a new world religion to unite the old religions?". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. March 26, 1921. p. 7. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Thompson, Juliet (1978). "Juliet Remembers Gibran as told to Marzieh Gail". World Order. Vol. 12, no. 4. pp. 29–31.

- ^ Kahlil Gibran; Barbara Young (1986). This Man from Lebanon: A Study of Kahlil Gibran. Knopf.

- ^ Lebanon: Situation of Baha'is, Government of Canada, 2004-04-16

- ^ Gibran, Khalil (1983). Blue Flame: The Love Letters of Khalil Gibran to May Ziadah. edited and translated by Suheil Bushrui and Salma Kuzbari. Harlow, England: Longman. ISBN 0-582-78078-0.

- ^ "The Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace at the Center for Heritage Resource Studies The University of Maryland". Heritage.umd.edu. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ "Professor Suheil Bushrui Receives Juliet Hollister Award". Steinergraphics.com. August 20, 2003. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ Alexandre Najjar, Kahlil Gibran, a biography, Saqi, 2008, p.110.

- ^ Najjar, op.cit., p.27, note 2

- ^ ""Pity The Nation..." by Khalil Gibran". Artsyhands.com. November 6, 2009. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ Adel Beshara (April 27, 2012). The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, Pioneers and Identity. Taylor & Francis. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-136-72450-3.

- ^ Hawi, Khalil Gibran: His Background, Character and Works, 1972, p219

- ^ "Gibran Memorial in Washington, DC". Dcmemorials.com. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ U.S. Society & Values; February 2000[dead link]

- ^ "Monument To Lebanese Poet Gibran Erected In Yerevan". Lebanonwire. November 26, 2005.

- ^ "Ժուբրանը` Մանկական այգում". Aravot (in Armenian). November 23, 2005.

Sources

- Gibran, Jean; Kahlil Gibran (1998) [1981]. Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World. Salma Khadra Jayyusi (foreword). New York: Interlink Books. ISBN 1-56656-249-X.

- Waterfield, Robin (1998). Prophet: The Life and Times of Kahlil Gibran. St. Martin's Press.

- Najjar, Alexandre, "Kahlil Gibran, a biography", Saqi, 2008.

- Khalil Gibran and Ameen Rihani: Prophets of Lebanese-American Literature. Ed. by Naji B. Oueijan, et al. Louaize: Notre Dame Press, 1999.

- Poeti arabi a New York. Il circolo di Gibran, introduzione e traduzione di F. Medici, prefazione di A. Salem, Palomar, Bari 2009. ISBN 978-88-7600-340-0.

- Daniel S. Larangé, Poétique de la fable chez Khalil Gibran (1883–1931): Les avatars d'un genre littéraire et musical: le maqam, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2005.

External links

- Khalil Gibran Museum, Bsharri, Lebanon

- Works by Kahlil Gibran at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Kahlil Gibran at the Internet Archive

- Works by Kahlil Gibran at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Online copies of texts by Gibran

- Works by Khalil Gibran

- BBC World Service: The Man Behind the Prophet

- The New Yorker: Prophet Motive

- The World According to http://www.kahlilgibran.com

- Khalil Gibran in the New York Times Archives

- Kahlil Gibran

- 1883 births

- 1931 deaths

- Deaths from cirrhosis

- 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- Catholic poets

- Cultural history of Boston

- Lebanese Maronites

- American Maronites

- Christian mystics

- People from Bsharri

- Infectious disease deaths in New York

- Ottoman novelists

- 20th-century Ottoman poets

- Lebanese emigrants to the United States

- American novelists of Ottoman descent

- 20th-century American poets

- 20th-century American novelists

- Alumni of the Académie Julian

- American short story writers of Lebanese descent

- American male novelists

- American male poets

- Male short story writers

- Ottoman male poets