Kelvin–Helmholtz instability

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2010) |

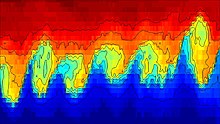

The Kelvin–Helmholtz instability (after Lord Kelvin and Hermann von Helmholtz) can occur when there is velocity shear in a single continuous fluid, or where there is a velocity difference across the interface between two fluids. An example is wind blowing over water: The instability manifests in waves on the water surface. More generally, clouds, the ocean, Saturn's bands, Jupiter's Red Spot, and the sun's corona show this instability.[1]

Overview

The theory predicts the onset of instability and transition to turbulent flow in fluids of different densities moving at various speeds.[3] Helmholtz studied the dynamics of two fluids of different densities when a small disturbance, such as a wave, was introduced at the boundary connecting the fluids.

For some short enough wavelengths, if surface tension is ignored, two fluids in parallel motion with different velocities and densities yield an interface that is unstable for all speeds. Surface tension stabilises the short wavelength instability however, and theory predicts stability until a velocity threshold is reached. The theory, with surface tension included, broadly predicts the onset of wave formation in the important case of wind over water.[citation needed]

It was recently discovered that the fluid equations governing the linear dynamics of the system admit a parity-time symmetry, and the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability occurs when and only when the parity-time symmetry breaks spontaneously.[4]

For a continuously varying distribution of density and velocity (with the lighter layers uppermost, so that the fluid is RT-stable), the dynamics of the KH instability is described by the Taylor–Goldstein equation and its onset is given by the Richardson number . Typically the layer is unstable for . These effects are common in cloud layers. The study of this instability is applicable in plasma physics, for example in inertial confinement fusion and the plasma–beryllium interface.

Numerically, the KH instability is simulated in a temporal or a spatial approach. In the temporal approach, experimenters consider the flow in a periodic (cyclic) box "moving" at mean speed (absolute instability). In the spatial approach, experimenters simulate a lab experiment with natural inlet and outlet conditions (convective instability).

See also

- Rayleigh–Taylor instability

- Richtmyer–Meshkov instability

- Mushroom cloud

- Plateau–Rayleigh instability

- Kármán vortex street

- Taylor–Couette flow

- Fluid mechanics

- Fluid dynamics

Notes

- ^ Fox, Karen C. "NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory Catches "Surfer" Waves on the Sun". NASA-The Sun-Earth Connection: Heliophysics. NASA.

- ^ Sutherland, Scott (March 23, 2017). "Cloud Atlas leaps into 21st century with 12 new cloud types". The Weather Network. Pelmorex Media. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Drazin, P. G. (2003). Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences. Elsevier Ltd. p. 1068–1072. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ Qin, H.; et al. (2019). "Kelvin-Helmholtz instability is the result of parity-time symmetry breaking". Physics of Plasmas. 26: 032102. arXiv:1810.11460. doi:10.1063/1.5088498.}

References

- Lord Kelvin (William Thomson) (1871). "Hydrokinetic solutions and observations". Philosophical Magazine. 42: 362–377.

- Hermann von Helmholtz (1868). "Über discontinuierliche Flüssigkeits-Bewegungen [On the discontinuous movements of fluids]". Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. 23: 215–228.

- Article describing discovery of K-H waves in deep ocean: Broad, William J. (April 19, 2010). "In Deep Sea, Waves With a Familiar Curl". New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

External links

- Hwang, K.-J.; Goldstein; Kuznetsova; Wang; Viñas; Sibeck (2012). "The first in situ observation of Kelvin-Helmholtz waves at high-latitude magnetopause during strongly dawnward interplanetary magnetic field conditions". J. Geophys. Res. 117 (A08233): n/a. Bibcode:2012JGRA..117.8233H. doi:10.1029/2011JA017256.

- Giant Tsunami-Shaped Clouds Roll Across Alabama Sky - Natalie Wolchover, Livescience via Yahoo.com

- Tsunami Cloud Hits Florida Coastline

- Vortex formation in free jet - YouTube video showing Kelvin Helmholtz waves on the edge of a free jet visualised in a scientific experiment.

- Wave clouds over Christchurch City

- Kelvin-Helmholtz clouds, in Barmouth, Gwynedd, on 18 February 2017