L'armata Brancaleone

| L'armata Brancaleone | |

|---|---|

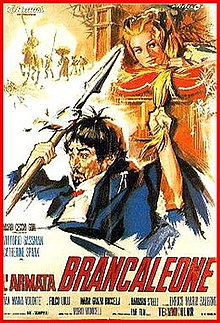

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mario Monicelli |

| Written by | Agenore Incrocci Furio Scarpelli Mario Monicelli |

| Produced by | Mario Cecchi Gori |

| Starring | Vittorio Gassman Catherine Spaak Gian Maria Volonté Folco Lulli Maria Grazia Buccella Barbara Steele Enrico Maria Salerno |

| Music by | Carlo Rustichelli |

| Distributed by | Titanus Film |

Release date |

|

Running time | 120 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Box office | $2.2 million (Italy)[1] |

L'armata Brancaleone (known in English-speaking countries as For Love and Gold or The Incredible Army of Brancaleone) is an Italian comedy film released on April 7, 1966, written by the duo Age & Scarpelli and directed by Mario Monicelli. It features Vittorio Gassman in the main role. It was entered into the 1966 Cannes Film Festival.[2]

The term Armata Brancaleone is still used today in Italian to define a group of badly assembled and poorly equipped people. Brancaleone is an actual historical name, meaning the paw of lions in heraldry jargon. Brancaleone degli Andalò was a governor of Rome in the Middle Ages.

Plot

[edit]The movie opens with a small Italian village being stormed by a band of Hungarian pillagers. When the murders and rapes are over, a German knight arrives and bravely kills the bandits. However, as he is healing his wounds he is attacked by two of the surviving villagers and one of the thieves. They throw the wounded knight into a river.

The attackers try to sell the knight's armor and weapons to a miserly Jewish merchant who finds among his belongings a letter of donation by the Holy Roman Emperor, granting the knight the fief of Aurocastro, an Apulian town. The parchment is torn at the lower end, which refers to a condition the knight must fulfill to enjoy the donation.

The Hungarian bandit comes up with the idea to propose a partnership to a cadet nobleman, so the group can take possession of the aforementioned fief and enjoy its riches. The knight they find is the poor and incompetent, yet well-meaning, Brancaleone da Norcia and they tell him that a noble knight handed them the parchment before dying. Brancaleone initially refuses the plan but after a farcical defeat at a jousting tournament that promised the hand of an overlord's daughter and a wealthy fief, he is too eager to take command of this "army" (L'Armata) of underdogs and lead it towards "fortune" and "glory", in what he sees as an epic journey.

As they set up towards the fief, Brancaleone lives several grotesque adventures, inspired by the confused and cosmopolitan world of Italy during Middle Ages; each one of them more hilarious than the last. These include:

- A Byzantine knight, Teofilatto dei Leonzi (Gian Maria Volonté), who proposes to fake his capture by the band so they can demand and share a ransom from his father.

- An entire city seemingly abandoned, which they begin to pillage, until they find out that it was depopulated by plague.

- A fanatical mad monk, Zenone (Enrico Maria Salerno), who promises that those who join his army of Crusaders will be "healed" from all ills, having the band follow him to a crusade in the Holy Land. When trying to convince his followers to cross a precarious bridge by leaping upon it (crying out loud that the Lord would protect them), the monk falls down into a deep gorge - this releases the band to follow their previous quest.

- The rescue of a bride named Matelda (Catherine Spaak), who falls in love with Brancaleone, but is rejected by him due to his oath to take her to her groom; to Brancaleone's misfortune, she avenges herself by losing her virginity to the Byzantine knight (by then a member of the gang); later, while the 'army' is relaxing at her nuptial feast her husband finds out about her state and she accuses Brancaleone of deflowering her.

- giving in to Teofilatto's plan, the army arrives at his father's castle to demand a ransom. His father refuses to pay, revealing that Teofilatto is his illegitimate child. Meanwhile, a confused Brancaleone has to fend off the sadomasochistically-fueled passion of Teofilatto's aunt, just one example of the inbred Byzantine household.

When finally the band reaches the fief, they discover that the missing part of their parchment mentioned that condition for the granting of the fief was that its new ruler should have provided adequate defences against the "black scourge coming from the sea", frequent raids by Saracen corsairs. Brancaleone designs a cartoonish Rube Goldberesque trap to defeat the Saracens, but instead the band ends up trapped within. As the band is about to be executed by impalement, it is saved by the knight of the opening scenes, the rightful owner of the fief, thirsty for vengeance against his attackers.

Brancaleone (who did not know about the attack on the knight) and his army are about to be burned alive when the mad monk arrives out of the blue and saves them from the knight, "so they can fulfill their duty to go onto the Holy Land". Being deprived of his dreams of richness, Brancaleone and his band agree to go along with the monk and his followers, saving themselves. Albeit sad, when he finds his untrustworthy horse, Brancaleone mounts and regains his confidence, taking the lead from the monk. The story is continued in a follow-up film, Brancaleone alle Crociate (1970).

Evaluation and themes

[edit]The plot is structured as a series of sketches revolving around different parodies of the Middle Ages world: it is itself a parody of the classical knights' quest typical of Middle Ages tales. Age and Scarpelli devised for the characters a striking, mocking form of a mixture of Italian (including its dialects) and Latin languages, which is probably the main feature of the film and one of the keys to its success. Gassman's overbearing and pompous recitation was also perfect for the role. The main musical theme of the film was also a great success.

According to Monicelli, the idea for the movie was spurred by a simple scene written by Age and Scarpelli, about two mediaeval peasants talking about women. Monicelli suggested that they shoot a movie which avoids the stereotypes of the usual Hollywood Middle Ages movies. It would instead show "the other face" of the era: poor people, underdogs, ignorance, mud, cold, misery.

There is no such stereotype left standing: the oppressed villagers are capable of violence themselves (they are prey to the bandits, but join them to attack their saving knight); the clergy, depicted by the hallucinating monk, fanatical to the extreme, always capable of explaining misfortunes by "lack of faith" of his entourage; the miserly Jewish merchant; the heroine/princess in distress, who instead of ending up with the hero asks to be deflowered by another man just to spite him. Finally, the archetypical medieval hero, the knight, has in the clueless Brancaleone its greatest parody, always jeopardized by following his chivalric code of conduct; as for his dreams of glory, he leads an army of underdogs that are a little more than a band of cowardly bandits who flee from fights and feign submission while actively trying to manipulate him from the bottom.

Underdogs and humiliated people were constantly present in Monicelli's art, but in this case they are shown mainly from a comical side. Another important theme of the film is male friendship, which was also an important element in movies such as La grande guerra and the later Amici miei.

The costumes often provide a near-surreal effect, particularly in the wedding banquet and Byzantine castle scenes. Their designer, Piero Gherardi, won a Silver Ribbon for them in 1967.

Reception

[edit]The film was the third-highest grossing Italian film in Italy for the year with a gross of $2,150,000.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Top Italian Film Grossers". Variety. October 11, 1967. p. 33.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: L'armata Brancaleone". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-03-07.