Laughter: Difference between revisions

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==Laughter in animals== |

==Laughter in animals== |

||

[[File:http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk/media/images/41038000/jpg/_41038521_manlaughing203.jpg]] |

[[File:http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk/media/images/41038000/jpg/_41038521_manlaughing203.jpg]] A PERFECT EXAMPLE OF LAUGHING! |

||

Laughter is not confined or unique to humans, despite Aristotle's observation that "only the human animal laughs". The differences between the laughter of chimpanzees and humans may be the result of adaptations that evolved to enable human speech. However, some behavioral psychologists argue that self-awareness of one's situation, or the ability to identify with another's predicament are prerequisites for laughter, and thus certain animals are not laughing in the "human manner". |

Laughter is not confined or unique to humans, despite Aristotle's observation that "only the human animal laughs". The differences between the laughter of chimpanzees and humans may be the result of adaptations that evolved to enable human speech. However, some behavioral psychologists argue that self-awareness of one's situation, or the ability to identify with another's predicament are prerequisites for laughter, and thus certain animals are not laughing in the "human manner". |

||

Revision as of 17:43, 9 March 2009

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2009) |

Laughter is an audible expression (written as ha ha ha or lol etc.), or appearance of merriment or happiness, or an inward feeling of joy and pleasure (laughing on the inside). It may ensue (as a physiological reaction) from jokes, tickling, and other stimuli. Inhaling nitrous oxide can also induce laughter; other drugs, such as cannabis, can also induce episodes of strong laughter. Strong laughter can sometimes bring an onset of tears or even moderate muscular pain.

Laughter is a part of human behaviour regulated by the brain. It helps humans clarify their intentions in social interaction and provides an emotional context to conversations. Laughter is used as a signal for being part of a group — it signals acceptance and positive interactions with others. Laughter is sometimes seemingly contagious, and the laughter of one person can itself provoke laughter from others as a positive feedback.[1] An extreme case of this is the Tanganyika laughter epidemic. This may account in part for the popularity of laugh tracks in situation comedy television shows.

The study of humor and laughter, and its psychological and physiological effects on the human body is called gelotology.

Laughter in animals

File:Http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk/media/images/41038000/jpg/ 41038521 manlaughing203.jpg A PERFECT EXAMPLE OF LAUGHING!

Laughter is not confined or unique to humans, despite Aristotle's observation that "only the human animal laughs". The differences between the laughter of chimpanzees and humans may be the result of adaptations that evolved to enable human speech. However, some behavioral psychologists argue that self-awareness of one's situation, or the ability to identify with another's predicament are prerequisites for laughter, and thus certain animals are not laughing in the "human manner".

Laughter is a rich experience and expression in human beings. Thus there are several shades of smiling and laughing expressions. They involve elaborate neurophysiological and physiological processes. Such laughter is not often seen in animals. Nevertheless, one can not deny occurrences of primitive laughter in terms of experience and expression in animals.[citation needed] Owners of pets can vouch on this point,[original research?] if they understand when their pet is happy and how it expresses the same.[citation needed]

According to Dr. Brian Carroll, self awareness is conscious concommitant of the physiological processes involving laughter or smiling reflex [response] and its grades, degrees or spectrum varies according to phylogenetic development, with no clear cut demarcation. The emotional ingredients [such as contempt, hatred, ridicule, sarcasm, love, amusement etc] are variable and involve different neurophysiological and physiological processes.[citation needed]

Self awareness and ability to identify with another's predicament may be prerequisite to intellectual jokes with specific references and contexts, but not for laughing behavior as such. Laughing also feels good.

Research of laughter in animals may identify new molecules to alleviate depression, disorders of excessive exuberance such as mania and ADHD, or addictive urges and mood imbalances.

Non-human primates

Chimpanzees, gorillas, bonobos and orangutans show laughter-like vocalizations in response to physical contact, such as wrestling, play chasing, or tickling. This is documented in wild and captive chimpanzees. Chimpanzee laughter is not readily recognizable to humans as such, because it is generated by alternating inhalations and exhalations that sound more like breathing and panting. It sounds similar to screeching. The differences between chimpanzee and human laughter may be the result of adaptations that have evolved to enable human speech. It is hard to tell, though, whether or not the chimpanzee is expressing joy. There are instances in which non-human primates have been reported to have expressed joy. One study analyzed and recorded sounds made by human babies and bonobos (also known as pygmy chimpanzees) when tickled. It found that although the bonobo’s laugh was a higher frequency, the laugh followed the same spectrographic pattern of human babies to include as similar facial expressions. Humans and chimpanzees share similar ticklish areas of the body such as the armpits and belly. The enjoyment of tickling in chimpanzees does not diminish with age. A chimpanzee laughter sample. Goodall 1968 & Parr 2005

Rats

It has been discovered that rats emit long, high frequency, ultrasonic, socially induced vocalization during rough and tumble play and when tickled. The vocalization is described a distinct “chirping”. Humans cannot hear the "chirping" without special equipment. It was also discovered that like humans, rats have "tickle skin". These are certain areas of the body that generate more laughter response than others. The laughter is associated with positive emotional feelings and social bonding occurs with the human tickler, resulting in the rats becoming conditioned to seek the tickling. Additional responses to the tickling were those that laughed the most also played the most, and those that laughed the most preferred to spend more time with other laughing rats. This suggests a social preference to other rats exhibiting similar responses. However, as the rats age, there does appear to be a decline in the tendency to laugh and respond to tickle skin. The initial goal of Jaak Panksepp and Jeff Burgdorf’s research was to track the biological origins of joyful and social processes of the brain by comparing rats and their relationship to the joy and laughter commonly experienced by children in social play. Although, the research was unable to prove rats have a sense of humour, it did indicate that they can laugh and express joy. Panksepp & Burgdorf 2003 Chirping by rats is also reported in additional studies by Brain Knutson of the National Institutes of Health. Rats chirp when wrestling one another, before receiving morphine, or when mating. The sound has been interpreted as an expectation of something rewarding. Science News 2001

Dogs

A dog laugh sounds similar to a normal pant. By analyzing the pant using a sonograph, this pant varies with bursts of frequencies, resulting in a laugh. When this recorded dog-laugh vocalization is played to dogs in a shelter setting, it can initiate play, promote pro-social behavior, and decrease stress levels. In a study by Simonet, Versteeg, and Storie, 120 subject dogs in a mid-size county animal shelter were observed. Dogs ranging from 4 months to 10 years of age were compared with and without exposure to a dog-laugh recording. The stress behaviors measured included panting, growling, salivating, pacing, barking, cowering, lunging, play-bows, sitting, orienting and lying down. The study resulted in positive findings when exposed to the dog laughing: significantly reduced stress behaviors, increased tail wagging and the display of a play-face when playing was initiated, and the increase of pro-social behavior such as approaching and lip licking were more frequent. This research suggests exposure to dog-laugh vocalizations can calm the dogs and possibly increase shelter adoptions. Simonet, Versteeg, & Storie 2005 A dog laughter sample. Simonet 2005

Humans

Recently researchers have shown infants as early as 17 days old have vocal laughing sounds or spontaneous laughter. Early Human Development 2006This conflicts with earlier studies indicating that babies usually start to laugh at about four months of age; J.Y.T. Greig writes, quoting ancient authors, that laughter is not believed to begin in a child until the child is forty days old. [2] "Laughter is Genetic" Robert R. Provine, Ph.D. has spent decades studying laughter. In his interview for WebMD, he indicated "Laughter is a mechanism everyone has; laughter is part of universal human vocabulary. There are thousands of languages, hundreds of thousands of dialects, but everyone speaks laughter in pretty much the same way.” Everyone can laugh. Babies have the ability to laugh before they ever speak. Children who are born blind and deaf still retain the ability to laugh. “Even apes have a form of ‘pant-pant-pant’ laughter.”

Provine argues that “Laughter is primitive, an unconscious vocalization.” And if it seems you laugh more than others, Provine argues that it probably is genetic. In a study of the “Giggle Twins,” two exceptionally happy twins were separated at birth and not reunited until 43 years later. Provine reports that “until they met each other, neither of these exceptionally happy ladies had known anyone who laughed as much as she did.” They reported this even though they both had been brought together by their adoptive parents they indicated were “undemonstrative and dour.” Provine indicates that the twins “inherited some aspects of their laugh sound and pattern, readiness to laugh, and perhaps even taste in humor.” WebMD 2002

Raju Mandhyan states "The physical and psychological benefits of laughter come second only to the physical and psychological benefits of sex."

Norman Cousins developed a recovery program incorporating megadoses of Vitamin C, along with a positive attitude, love, faith, hope, and laughter induced by Marx Brothers films. "I made the joyous discovery that ten minutes of genuine belly laughter had an anesthetic effect and would give me at least two hours of pain-free sleep," he reported. "When the pain-killing effect of the laughter wore off, we would switch on the motion picture projector again and not infrequently, it would lead to another pain-free interval." He wrote about these experiences in several books.[3][4]

Gender differences

Men and women take jokes differently. A study that appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found in a study, 10 men and 10 women all watched 10 cartoons, rating them funny or not funny and if funny, how funny on a scale of 1–10. While doing this, their brains were scanned by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Men and women for the most part agreed which cartoons were funny. However, their brains handled humor differently. Women’s brains showed more activity in certain areas, including the nucleus accumbens. When women viewed cartoons they did not find humorous, their nucleus accumbens had a “ho-hum response.” A man's nucleus accumbens did not react to funny cartoons, and its natural activity level dropped during unfunny cartoons.

Researchers suspect the element of surprise may be at the heart of the study. They suggested that maybe women did not expect the cartoons to be funny, while men did the opposite. When the men in the study “got what they expected, their nucleus accumbens were calm.” However, the women’s brains could have had increased activity when they were “pleasantly surprised” by the cartoons’ humour. Researchers also suspect that men might have been “let down by unfunny cartoons, causing a dip in that brain area’s activity.”

It was indicated that this study might be a clue about the different emotional responses between men and women and could help with depression research. The research suggests men and women “differ in how humour is used and appreciated,” says Allan Reiss, M.D. WebMD 2005

Therapeutic benefits

The analgesic effect of laughing has been showed in many studies[5]. This is especially available for the relief of chronic pain in arthritis, spine lesions, neurological diseases etc. Doctors are of opinion that laughing brings about the secretion of endorphins into blood. More than that, it is known that laughing is a strong muscle-relaxing method, which also relieves pain.

Laughter can also be called "inner jogging", because similar to morning jogging, the blood pressure increases and then it gradually lowers till it gets lower than the initial blood pressure. A person with hypertension, however, should not consider experimenting - laughing isn't a method of intensive therapy.[6]

Laughter is a type of respiratory gymnastics. It corresponds to the Sanskrit name of "hasya-yoga". "Ho-ho" goes from the diaphragm, "ha-ha" goes from the heart or from the thorax, "hi-hi" – from the 'third eye'. It would be perfect to learn and use all these types of laughing with therapeutic purposes, but the most important laugh today is considered to be the deep one, the so-called guffaw.

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine led by Michael Miller, M.D. have identified a link between laughter and blood vessel dilation. Specifically, they found that after watching a video that induced sustained laughter over a 20 minute period, a 35% increase in brachial artery dilation was observed. The researchers hypothesize that emotional laughter releases endorphins that activate the endothelium to release nitric oxide thereby resulting in vessel dilation and increased blood flow. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=laughter-proves-good-medi

The laughter is considered to be a method of fighting stress (it inhibits the secretion of 4 main stress hormones). Recently, Japanese scientists discovered that laughing directly influences glucose level in blood.

Greek researchers have found through an experiment that 10-15 minutes of laughing burn from 10 to 40 calories, which leads to a weight loss of almost 4.5 lb (2 kg) per year.[7]

Laughter and the brain

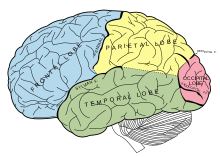

Modern neurophysiology states that laughter is linked with the activation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which produces endorphins after a rewarding activity.

Research has shown that parts of the limbic system are involved in laughter[citation needed]. The limbic system is a primitive part of the brain that is involved in emotions and helps us with basic functions necessary for survival. Two structures in the limbic system are involved in producing laughter: the amygdala and the hippocampus[citation needed].

The December 7, 1984 Journal of the American Medical Association describes the neurological causes of laughter as follows:

- "Although there is no known 'laugh center' in the brain, its neural mechanism has been the subject of much, albeit inconclusive, speculation. It is evident that its expression depends on neural paths arising in close association with the telencephalic and diencephalic centers concerned with respiration. Wilson considered the mechanism to be in the region of the mesial thalamus, hypothalamus, and subthalamus. Kelly and co-workers, in turn, postulated that the tegmentum near the periaqueductal grey contains the integrating mechanism for emotional expression. Thus, supranuclear pathways, including those from the limbic system that Papez hypothesised to mediate emotional expressions such as laughter, probably come into synaptic relation in the reticular core of the brain stem. So while purely emotional responses such as laughter are mediated by subcortical structures, especially the hypothalamus, and are stereotyped, the cerebral cortex can modulate or suppress them."

Causes

Common causes for laughter are sensations of joy and humor, however other situations may cause laughter as well.

A general theory that explains laughter is called the relief theory. Sigmund Freud summarized it in his theory that laughter releases tension and "psychic energy". This theory is one of the justifications of the beliefs that laughter is beneficial for one's health.[8] This theory explains why laughter can be as a coping mechanism for when one is upset, angry or sad.

Philosopher John Morreall theorizes that human laughter may have its biological origins as a kind of shared expression of relief at the passing of danger.

For example, this is how this theory works in the case of humor: a joke creates an inconsistency, the sentence appears to be not relevant, and we automatically try to understand what the sentence says, supposes, doesn't say, and implies; if we are successful in solving this 'cognitive riddle', and we find out what is hidden within the sentence, and what is the underlying thought, and we bring foreground what was in the background, and we realize that the surprise wasn't dangerous, we eventually laugh with relief. Otherwise, if the inconsistency is not resolved, there is no laugh, as Mack Sennett pointed out: "when the audience is confused, it doesn't laugh" (this is the one of the basic laws of a comedian, called "exactness"). It is important to note that the inconsistency may be resolved, and there may still be no laugh. Due to the fact that laughter is a social mechanism, we may not feel like we are in danger, however, the physical act of laughing may not take place. In addition, the extent of the inconsistency (timing, rhythm, etc) has to do with the amount of danger we feel, and thus how intense or long we laugh. This explanation is also confirmed by modern neurophysiology (see section Laughter and the Brain).

Notes

- ^ Camazine, Deneubourg, Franks, Sneyd, Theraulaz, Bonabeau, Self-Organization in Biological Systems, Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-691-11624-5 --ISBN 0-691-01211-3 (pbk.) p. 18

- ^ J.Y.T. Greig, The Psychology of Comedy and Laughter

- ^ Cousins, Norman, The Healing Heart : Antidotes to Panic and Helplessness, New York : Norton, 1983. ISBN 0393018164

- ^ Cousins, Norman, Anatomy of an illness as perceived by the patient : reflections on healing and regeneration, introd. by René Dubos, New York : Norton, 1979. ISBN 0393012522

- ^ Citation needed

- ^ Give Your Body a Boost -- With Laughter

- ^ "Laughing Therapy". InfoNIAC.com. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ M.P. Mulder, A. Nijholt (2002) "Humor Research: State of the Art"

References

- Bachorowski, J.-A., Smoski, M.J., & Owren, M.J. The acoustic features of human laughter. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 110 (1581) 2001

- Bakhtin, Mikhail (1941). Rabelais and his world. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Chapman, Antony J.; Foot, Hugh C.; Derks, Peter (editors), Humor and Laughter: Theory, Research, and Applications, Transaction Publishers, 1996. ISBN 1560008377

- Cousins, Norman, Anatomy of an Illness As Perceived by the Patient, 1979.

- Fried, I., Wilson, C.L., MacDonald, K.A., and Behnke EJ. Electric current stimulates laughter. Nature, 391:650, 1998 (see patient AK)

- Goel, V. & Dolan, R. J. The functional anatomy of humor: segregating cognitive and affective components. Nature Neuroscience 3, 237 - 238 (2001).

- Greig, John Young Thomson, The Psychology of Comedy and Laughter, New York, Dodd, Mead and company, 1923.

- Marteinson, Peter, On the Problem of the Comic: A Philosophical Study on the Origins of Laughter, Legas Press, Ottawa, 2006.

- Miller M, Mangano C, Park Y, Goel R, Plotnick GD, Vogel RA.Impact of cinematic viewing on endothelial function.Heart. 2006 Feb;92(2):261-2.

- Provine, R. R., Laughter. American Scientist, V84, 38:45, 1996.

- Quentin Skinner (2004). "Hobbes and the Classical Theory of Laughter" (pdf). Retrieved 2006-10-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) included in book: Sorell, Tom. "6". Leviathan After 350 Years. Oxford University Press. pp. 139–66. ISBN 13: 978-0-19-926461-2 ISBN 10: 0-19-926461-9.{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Raskin, Victor, Semantic Mechanisms of Humor (1985).

- MacDonald, C., "A Chuckle a Day Keeps the Doctor Away: Therapeutic Humor & Laughter" Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services(2004) V42, 3:18-25

- Kawakami, K., et al, Origins of smile and laughter: A preliminary study Early Human Development (2006) 82, 61-66

- Johnson, S., Emotions and the Brain Discover (2003) V24, N4

- Panksepp, J., Burgdorf, J., “Laughing” rats and the evolutionary antecedents of human joy? Physiology & Behavior (2003) 79:533-547

- Milius, S., Don't look now, but is that dog laughing? Science News (2001) V160 4:55

- Simonet, P., et al, Dog Laughter: Recorded playback reduces stress related behavior in shelter dogs 7th International Conference on Environmental Enrichment (2005)

- Discover Health (2004) Humor & Laughter: Health Benefits and Online Sources

- Klein, A. The Courage to Laugh: Humor, Hope and Healing in the Face of Death and Dying. Los Angeles, CA: Tarcher/Putman, 1998.

- Ron Jenkins Subversive laughter (New York, Free Press, 1994), 13ff

- Bogard, M. Laughter and its Effects on Groups. New York, New York: Bullish Press, 2008.

- Humor Theory. The formulae of laughter by Igor Krichtafovitch, Outskitspress, 2006, ISBN 9781598002225

See also

- Evil laugh

- Fatal hilarity

- Gelotology

- Laughter in Literature

- Nervous laughter

- Pathological laughing and crying

- Joke

External links

- The Origins of Laughter

- Humor therapy for cancer patients

- Etymology of Gelotology

- More information about Gelotology from the University of Washington

- How Stuff Works - Laughter

- Where Did Laughter Come From?

- Humor Theory

- Formulae of laughter

- WNYC's Radio Lab radio show: Is Laughter just a Human Thing?