Austen Henry Layard

Sir Austen Henry Layard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 12 February 1852 – 21 February 1852 | |

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Prime Minister | Lord John Russell |

| Preceded by | The Lord Stanley of Alderley |

| Succeeded by | Lord Stanley |

| In office 15 August 1861 – 26 June 1866 | |

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Palmerston The Earl Russell |

| Preceded by | The Lord Wodehouse |

| Succeeded by | Edward Egerton |

| First Commissioner of Works | |

| In office 9 December 1868 – 26 October 1869 | |

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Prime Minister | William Ewart Gladstone |

| Preceded by | Lord John Manners |

| Succeeded by | Acton Smee Ayrton |

| Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office 1877–1880 | |

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Preceded by | Sir Henry Elliot |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Dufferin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 March 1817 Paris, France |

| Died | 5 July 1894 (aged 77) London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Mary Enid Evelyn Guest |

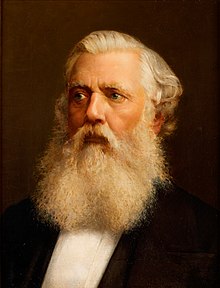

Sir Austen Henry Layard GCB PC (/lɛərd/; 5 March 1817 – 5 July 1894) was an English Assyriologist, traveller, cuneiformist, art historian, draughtsman, collector, politician and diplomat. He was born to a mostly English family in Paris and largely raised in Italy. He is best known as the excavator of Nimrud and of Nineveh, where he uncovered a large proportion of the Assyrian palace reliefs known, and in 1851 the library of Ashurbanipal. Most of his finds are now in the British Museum. He made a large amount of money from his best-selling accounts of his excavations.

He had a political career between 1852, when he was elected as a Member of Parliament, and 1869, holding various junior ministerial positions. He was then made ambassador to Madrid, then Constantinople, living much of the time in a palazzo he bought in Venice. During this period he built up a significant collection of paintings, which due to a legal loophole he had as a diplomat, he was able to extricate from Venice and bequeath to the National Gallery (as the Layard Bequest) and other British museums.[1][2]

Family

[edit]Layard was born in Paris, France, to a family of Huguenot descent. His father, Henry Peter John Layard, of the Ceylon Civil Service, was the son of Charles Peter Layard, Dean of Bristol, and grandson of Dr Daniel Peter Layard, a physician. His mother, Marianne, daughter of Nathaniel Austen, banker, of Ramsgate, was of partial Spanish descent.[3] His uncle was Benjamin Austen, a London solicitor and close friend of Benjamin Disraeli in the 1820s and 1830s. Edgar Leopold Layard the ornithologist was his brother.

On 9 March 1869, at St. George's Church, Hanover Square, Westminster, London, he married his first cousin once removed, Mary Enid Evelyn Guest. Enid, as she was known, was the daughter of Sir Josiah John Guest and Lady Charlotte Elizabeth Bertie. Their marriage was reportedly a happy one, and they never had any children.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Much of Layard's boyhood was spent in Italy, where he received part of his schooling, and acquired a taste for the fine arts and a love of travel from his father; but he was at school also in England, France and Switzerland. After spending nearly six years in the office of his uncle, Benjamin Austen, he was tempted to leave England for Sri Lanka (Ceylon) by the prospect of obtaining an appointment in the Civil Service, and he started in 1839 with the intention of making an overland journey across Asia.[3]

After wandering for many months, chiefly in Persia, with Bakhtiari people and having abandoned his intention of proceeding to Ceylon, he returned in 1842 to the Ottoman capital Constantinople where he made the acquaintance of Sir Stratford Canning, the British Ambassador, who employed him in various unofficial diplomatic missions in European Turkey. In 1845, encouraged and assisted by Canning, Layard left Constantinople to make those explorations among the ruins of Assyria with which his name is chiefly associated. This expedition was in fulfilment of a design which he had formed when, during his former travels in the East, his curiosity had been greatly excited by the ruins of Nimrud on the Tigris, and by the great mound of Kuyunjik, near Mosul, already partly excavated by Paul-Émile Botta.[3]

Excavations and the arts

[edit]

Layard remained in the neighbourhood of Mosul, carrying on excavations at Kuyunjik and Nimrud, and investigating the condition of various peoples, until 1847; and, returning to England in 1848, published Nineveh and Its Remains (2 vols., 1848–1849).[3]

To illustrate the antiquities described in this work he published a large folio volume of The Monuments of Nineveh. From Drawings Made on the Spot (1849). After spending a few months in England, and receiving the degree of D.C.L. from the University of Oxford and the Founder's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society, Layard returned to Constantinople as attaché to the British embassy, and, in August 1849, started on a second expedition, in the course of which he extended his investigations to the ruins of Babylon and the mounds of southern Mesopotamia. He is credited with discovering the Library of Ashurbanipal during this period. His record of this expedition, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon,[4] which was illustrated by another folio volume, called A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh, was published in 1853. During these expeditions, often in circumstances of great difficulty, Layard despatched to England the splendid specimens which now form the greater part of the collection of Assyrian antiquities in the British Museum.[3] Layard believed that the native Syriac Christian communities living throughout the Near East were descended from the ancient Assyrians.[5]

Apart from the archaeological value of his work in identifying Kuyunjik as the site of Nineveh, and in providing a great mass of materials for scholars to work upon, these two books of Layard were among the best written books of travel in the English language.[3]

Layard was an important member of the Arundel Society,[6] and in 1866 he was appointed a trustee of the British Museum.[3] In the same year Layard founded "Compagnia Venezia Murano" and opened a venetian glass showroom in London at 431 Oxford Street. Today Pauly & C. - Compagnia Venezia Murano is one of the most important brands of venetian art glass production.

Political career

[edit]

Layard now turned to politics. Elected as a Liberal member for Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire in 1852, he was for a few weeks Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, but afterwards freely criticised the government, especially in connection with army administration. He was present in the Crimea during the war, and was a member of the committee appointed to inquire into the conduct of the expedition. In 1855 he refused from Lord Palmerston an office not connected with foreign affairs, was elected lord rector of Aberdeen University, and on 15 June moved a resolution in the House of Commons (defeated by a 359–46 majority[7]) declaring that in public appointments merit had been sacrificed to private influence and an adherence to routine. After being defeated at Aylesbury in 1857, he visited India to investigate the causes of the Indian Mutiny. He unsuccessfully contested York in 1859, but was elected for Southwark in 1860, and from 1861 to 1866 was Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs in the successive administrations of Lord Palmerston and Lord John Russell.[3] After the Liberals returned to office in 1868 under William Ewart Gladstone, Layard was made First Commissioner of Works and sworn of the Privy Council.[8]

Diplomatic career

[edit]Layard resigned from office in 1869, on being sent as envoy extraordinary to Madrid.[9] In 1877 he was appointed by Lord Beaconsfield Ambassador at Constantinople, where he remained until Gladstone's return to power in 1880, when he finally retired from public life. In 1878, on the occasion of the Berlin Congress, he was appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath.[3]

Retirement in Venice

[edit]

Layard retired to Venice. There he took up residence in the sixteenth-century palazzo on the grand canal named Ca Cappello, just behind Campo San Polo, and which he had commissioned historian Rawdon Brown, another long-time British resident of Venice, to purchase for him in 1874.[10] In Venice he devoted much of his time to collecting pictures of the Venetian school, and to writing on Italian art. On this subject he was a disciple of his friend Giovanni Morelli, whose views he embodied in his revision of Franz Kugler's Handbook of Painting, Italian Schools (1887). He wrote also an introduction to Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes's translation of Morelli's Italian Painters (1892–1893), and edited that part of Murray's Handbook of Rome (1894) which deals with pictures. In 1887 he published, from notes taken at the time, a record of his first journey to the East, entitled Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana and Babylonia. The late nineteenth century English novelist George Gissing thought it 'one of the most interesting books' vowing to 'read it again some day'.[11] An abbreviation of this work, which as a book of travel is even more delightful than its predecessors, was published in 1894, shortly after the author's death, with a brief introductory notice by Lord Aberdare. Layard also from time to time contributed papers to various learned societies, including the Huguenot Society, of which he was first president.[3]

He died on 5 July 1894 at his residence 1 Queen Anne Street, Marylebone, London.[12] After a post mortem autopsy his remains were cremated at the Woking Crematorium in Surrey. His ashes were interred in the cemetery of Canford Magna Parish Church in Dorset, England.

Publications

[edit]- Layard, A.H. (1849), Nineveh and its remains : with an account of a visit to the Chaldean Christians of Kurdistan, and the Yezidis, or devil worshippers; and an inquiry into the manners and arts of the ancient Assyrians, John Murray, London, 2 volumes

- Layard, A.H., The Monuments of Nineveh., John Murray (London)

- First series, 1849 , 100 plates, From Drawings Made on the Spot.

- Second series, 1853 , 71 plates, A Second Series [..] including Bas-Reliefs from the Palace of Sennacherib and Bronzes from the Ruins of Nimroud. From drawings made on the spot during a second expedition to Assyria. (alt. plates only)

- Layard, A.H. (1851), Inscriptions in the Cuneiform Character, from Assyrian monuments, discovered by A. H. Layard, D.C.L. (PDF), Harrison & Son (London)

- Layard, A.H. (1852), A Popular Account of Discoveries at Nineveh., John Murray (London) , abridged version of Nineveh and its remains (1849)

- Layard, A.H. (1853), Discoveries among the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon; with travels in Armenia, Kurdistan, and the desert: being the result of a second expedition undertaken for the Trustees of the British museum, Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, John Murray (London)

- Layard, A.H. (1854), The Ninevah Court in the Crystal Palace., John Murray (London)

- Layard, A.H. (1857), The Madonna and saints painted in fresco by Ottaviano Nelli, in the church of S. Maria Nuova at Gubbio, John Murray (London)

- Layard, A.H. (1867), Nineveh and Babylon A narrative of a second expedition to Assyria, during the years 1849, 1850, and 1851, John Murray (London) , abridged version of Nineveh and Babylon (1853)

- Layard, A.H. (1887), The Italian schools of painting – based on the handbook of Kugler, John Murray (London)

- Layard, A.H. (1887), Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia., John Murray (London) , 2 volumes

- Layard, A.H. (1903), Bruce, William N. (ed.), Autobiography and Letters from his childhood until his appointment as H.M. Ambassador at Madrid., John Murray (London) , 2 volumes, biography

References

[edit]- ^ "Austen Henry Layard", National Gallery

- ^ Rivista enciclopedica contemporanea, Editore Francesco Vallardi, Milan, (1913), entry by UN, pages 16-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Layard, Sir Austen Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 312.

- ^ Layard, Austen Henry (1853). "Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon..." Internet Archive. G. P. Putnam and Co. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ Cross, Frank Leslie (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

In the 19th cent. A. H. Layard, the excavator of Nineveh, first suggested that the local *Syriac Christian communities in the region were descended from the ancient Assyrians, and the idea was later popularized by W. A. Wigram, a member of the Abp. Of Canterbury's Mission to the Church of the East (1895–1915).

- ^ Layard 1903, Vol.1, p.vi.

- ^ Briggs, Asa: The Age of Improvement, 1783–1867 (2nd edition), p. 377. Routledge, 2000

- ^ "No. 23449". The London Gazette. 11 December 1868. p. 6581.

- ^ "Sir Henry Layard", Eminent persons: Biographies reprinted from the Times, vol. VI (1893–1894), Macmillan & Co., p. 134, 1897

- ^ Parry, Jonathan (2006). "Layard, Sir Austen Henry (1817–1894), archaeologist and politician". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16218. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Coustillas, Pierre ed. London and the Life of Literature in Late Victorian England: the Diary of George Gissing, Novelist. Brighton: Harvester Press, 1978, p.318.

- ^ Philip Temple, Colin Thom, Andrew Saint (2017) Survey of London: South-East Marylebone Volumes 51 and 52 Yale University Press

Further reading

[edit]- Brackman, Arnold C. (1978), The Luck of Nineveh: Archaeology's Great Adventure, McGraw-Hill Book Company, ISBN 0-07-007030-X, also published by Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1981, paperback, ISBN 0-442-28260-5.

- Jerman, B.R. (1960), The Young Disraeli, Princeton University Press

- Kubie, Nora Benjamin (1964), Road to Nineveh: the adventures and excavations of Sir Austen Henry Layard

- Larsen, Mogens T. (1996), The Conquest of Assyria, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-14356-X

- Lloyd, Seton. (1981), Foundations in the Dust: The Story of Mesopotamian Exploration, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-05038-4

- Waterfield, Gordon. (1963), Layard of Nineveh, John Murray

- Sinan, Kuneralp, ed. (2009), The Queen's Ambassador to the Sultan. Memoirs of Sir Henry A. Layard's Constantinople Embassy 1877–1880, The ISIS Press, Istanbul, ISBN 978-975-428-395-2

- Silverberg, Robert. (1964), The man who found Nineveh. The story of Austen Henry Layard, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

External links

[edit]- Works by Austen Henry Layard at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Austen Henry Layard at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Austen Henry Layard

- Feature about the Lanyard and Blenkinsopp Coulson Archives

- 1817 births

- 1894 deaths

- Archaeologists of Nineveh

- English Assyriologists

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- Rectors of the University of Aberdeen

- Trustees of the British Museum

- UK MPs 1852–1857

- UK MPs 1859–1865

- UK MPs 1865–1868

- UK MPs 1868–1874

- Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to the Ottoman Empire

- Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Spain

- Victorian writers

- 19th-century English writers

- 19th-century British archaeologists

- 19th-century British diplomats

- Burials in Dorset

- British expatriates in the Ottoman Empire

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)