Luca Pacioli

Fra Luca Bartolomeo de Pacioli (sometimes Paciolo) (1445–1514 or 1517) was an Italian mathematician and Franciscan friar, collaborator with Leonardo da Vinci, and seminal contributor to the field now known as accounting. He was also called Luca di Borgo after his birthplace, Borgo Santo Sepolcro, Tuscany.

Life

Luca Pacioli studied in Venice and Rome and became a Franciscan friar in the 1470s. He was a travelling mathematics tutor until 1497, when he accepted an invitation from Lodovico Sforza ("Il Moro") to work in Milan. There he collaborated with, lived with, and taught mathematics to Leonardo da Vinci. In 1499, Pacioli and Leonardo were forced to flee Milan when Louis XII of France seized the city and drove their patron out. After that, Pacioli and Leonardo frequently traveled together. Upon return to his hometown, Pacioli died of old age in 1517.

Mathematics

Pacioli published several works on mathematics, including:

- Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita (Venice 1494), a synthesis of the mathematical knowledge of his time, is also notable for including the first published description of the method of keeping accounts that Venetian merchants used during the Italian Renaissance, known as the double-entry accounting system. Although Pacioli codified rather than invented this system, he is widely regarded as the "Father of Accounting". The system he published included most of the accounting cycle as we know it today. He described the use of journals and ledgers, and warned that a person should not go to sleep at night until the debits equalled the credits. His ledger had accounts for assets (including receivables and inventories), liabilities, capital, income, and expenses—the account categories that are reported on an organization's balance sheet and income statement, respectively. He demonstrated year-end closing entries and proposed that a trial balance be used to prove a balanced ledger. Also, his treatise touches on a wide range of related topics from accounting ethics to cost accounting.

- De viribus quantitatis (Ms. Università degli Studi di Bologna, 1496–1508), a treatise on mathematics and magic. Written between 1496 and 1508 it contains the first reference to card tricks as well as guidance on how to juggle, eat fire and make coins dance. It is the first work to note that Da Vinci was left-handed. De viribus quantitatis is divided into three sections: mathematical problems, puzzles and tricks, and a collection of proverbs and verses. The book has been described as the "foundation of modern magic and numerical puzzles", but it was never published and sat in the archives of the University of Bologna, seen only by a small number of scholars since the Middle Ages. The book was rediscovered after David Singmaster, a mathematician, came across a reference to it in a 19th-century manuscript. An English translation was published for the first time in 2007.[2]

- Geometry (1509), a Latin translation of Euclid.

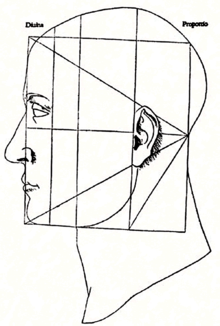

- De divina proportione (written in Milan in 1496–98, published in Venice in 1509). Two versions of the original manuscript are extant, one in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, the other in the Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire in Geneva. The subject was mathematical and artistic proportion, especially the mathematics of the golden ratio and its application in architecture. Leonardo da Vinci drew the illustrations of the regular solids in De divina proportione while he lived with and took mathematics lessons from Pacioli. Leonardo's drawings are probably the first illustrations of skeletonic solids, which allowed an easy distinction between front and back. The work also discusses the use of perspective by painters such as Piero della Francesca, Melozzo da Forlì, and Marco Palmezzano. As a side note, the "M" logo used by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is taken from De divina proportione.[citation needed]

The Ancients, having taken into consideration the rigorous construction of the human body, elaborated all their works, as especially their holy temples, according to these proportions; for they found here the two principal figures without which no project is possible: the perfection of the circle, the principle of all regular bodies, and the equilateral square.

— De divina proportione

Translation of Piero della Francesca's work

The third volume of Pacioli's De divina proportione was an Italian translation of Piero della Francesca's Latin writings On [the] Five Regular Solids, but it did not include an attribution to Piero. He was severely criticized for that by sixteenth-century art historian and biographer Giorgio Vasari. On the other hand, R. Emmett Taylor (1889–1956) said that Pacioli may have had nothing to do with that volume of translation, and that it may just have been appended to his work.

Chess

Pacioli also wrote an unpublished treatise on chess, De ludo schaccorum (On the Game of Chess). Long thought to have been lost, a surviving manuscript was rediscovered in 2006, in the 22,000-volume library of Count Guglielmo Coronini. Based on Leonardo da Vinci's long association with the author and his having illustrated De divina proportione, some scholars speculate that Leonardo either drew the chess problems that appear in the manuscript or at least designed the chess pieces used in the problems.[1][2][3]

Footnotes

References

- Bambach, Carmen (2003). "Leonardo, Left-Handed Draftsman and Writer". New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- Pacioli, Luca. De divina proportione (English: On the Divine Proportion), Luca Paganinem de Paganinus de Brescia (Antonio Capella) 1509, Venice

- Taylor, Emmet, R. No Royal Road: Luca Pacioli and his Times (1942)

- Luca Pacioli: The Father of Accounting

- Full Biography of Pacioli (St.Andrews)

- Lucas Pacioli - Catholic Encyclopedia article