Maggi Hambling

Maggi Hambling | |

|---|---|

Hambling in 2006 | |

| Born | 23 October 1945[1] Sudbury, Suffolk, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | |

| Known for | painting, sculpture |

| Awards |

|

| Website | maggihambling |

Maggi Hambling CBE (born 23 October 1945) is a British painter and sculptor. Perhaps her best-known public works are the sculptures A Conversation with Oscar Wilde in London and Scallop, a 4-metre-high steel piece on Aldeburgh beach dedicated to Benjamin Britten. Both works have attracted a great degree of controversy.[2]

Early life and education

Maggi Hambling was born in Sudbury, Suffolk[3] She had two siblings, a sister, Ann, who was 11 years older, and a brother, Roger, nine years older than Hambling. Her brother had wanted a brother but ignored the fact that his younger sibling is female and taught her carpentry and "how to wring a chicken's neck." Hambling was close to her mother who taught ballroom dancing and took Hambling along to be her partner. It was from her father that she inherited her artistic skills. She was not as close to her father as she was to her mother but when her father retired at the age of 60, Hambling gave her some oil paints and discovered that she had a knack for painting.[4]

Hambling first studied art under Yvonne Drewry at the Amberfield School in Nacton. She then studied at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing from 1960 under Cedric Morris and Lett Haines, then at Ipswich School of Art (1962–64), Camberwell (1964–67), and finally the Slade School of Art, graduating in 1969.[5]

Career

Hambling is a painter as well as a sculptor. She is known for her intricate land and seascapes, including a celebrated series of North Sea paintings.[6] She is also known for her portraits, with several works in the National Portrait Gallery, London.[7]

In 1980 Hambling became the first artist in residence at the National Gallery, after which she produced a series of portraits of the comedian Max Wall.[8] Wall responded to Hambling's request to paint him with a letter saying: "Re: painting little me, I am flattered indeed – what colour?"[3][9] She has taught at Wimbledon School of Art.[10]

Women feature prominently in her portrait series. For example, Hambling was commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery to paint Professor Dorothy Hodgkin in 1985. The portrait features Hodgkin at a desk with four hands, all engaged in different tasks.[11] Her wider body of work is held in many public collections including the British Museum, Tate Collection, National Gallery, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Hambling is known for her choice in painting the dead. She states that it is her way of grieving for those who are gone, particularly her way of coping with the death of those she held close like Henrietta Moraes, her mother, father in their coffins. Hambling tells NYTimes George Melly gave her the nickname of "Maggi (coffin) Hambling" and joked that this is the name she would be known by. Her work is spurred through anger—for the destruction of the planet, about politics, for social issues.[citation needed]

In 2013, she exhibited at Snape during the Aldeburgh Festival, and a solo exhibition was held at the Hermitage, St Petersburg.[citation needed]

Hambling is frequently described as a controversial figure.

Hambling is a Patron of Paintings in Hospitals, a charity that provides art for health and social care in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.[12]

Works and reception

Memorial to Oscar Wilde

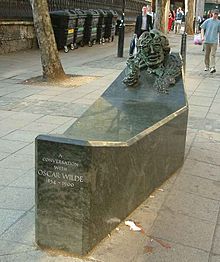

In 1998 Hambling completed this outdoor sculpture in central London as a memorial to the dramatist Oscar Wilde, the first public monument to him outside his native Ireland.[13]

Fans of Wilde, notably Derek Jarman, first suggested a memorial in the 1980s. A committee, led by Sir Jeremy Isaacs and including the actors Dame Judi Dench and Sir Ian McKellen and the poet Seamus Heaney, raised the money and commissioned Hambling.[14] Her design features Wilde's bronze head rising from a green granite sarcophagus which also serves as a bench; Wilde's hand was holding a cigarette. The work is inscribed with a quotation from his play Lady Windermere's Fan: "We are all in the gutter but some of us are looking at the stars".[14]

Some critics were visceral in their loathing of the work,[15] but supporters said it was well-loved by the public.[16] The chief art critic of The Independent,[17] wrote that ultimately the sculpture was not about Wilde or the viewing public, but a reflection of Hambling herself.[18]

The cigarette was repeatedly removed by members of the public,[19] "the most frequent act of vandalism/veneration done to a public statue in London",[20] and is now no longer replaced.

Memorial to Benjamin Britten

Scallop (2003) celebrates the composer Benjamin Britten and stands on the beach at Aldeburgh, Suffolk, near where he lived and not far from Hambling's village.[21] The four-metre-high (13 ft) steel sculpture is pierced with the words "I hear those voices that will not be drowned" from his opera Peter Grimes. Britten was a homosexual and a conscientious objector during World War II, and his memorial was opposed by some.[22]

Hambling describes Scallop as a conversation with the sea:

- "An important part of my concept is that at the centre of the sculpture, where the sound of the waves and the winds are focused, a visitor may sit and contemplate the mysterious power of the sea."[23]

Throughout antiquity, scallops and other hinged shells have symbolised the feminine principle.[24] The outside of the shell represents protection, and the inside, the "life-force slumbering within the Earth",[25] an emblem of the vulva.[26][27] Many paintings of Venus, the Roman goddess of love and fertility, included a scallop shell to identify her, as for example in Botticelli's The Birth of Venus.[28]

The scallop is the traditional emblem of St James the Great and hence was chosen by pilgrims returning from the Way of St James (Camino de Santiago).[29] The scallop shell found its way into heraldry as a badge of those who had walked all the way to the apostle's shrine at Santiago de Compostela in Galicia; later it became a symbol of pilgrimage in general. The scallop shell is also associated with Saint Augustine and his attempts to understand the mysteries of the divine.[30]

For this work, Hambling received the 2006 Marsh Award for Excellence in Public Sculpture.[31]

Proposed memorial to Mary Wollstonecraft

In May 2018, Hambling was chosen to create a statue commemorating Mary Wollstonecraft, the “foremother of feminism”. The Mary on the Green campaign has been working to erect a permanent memorial to the philosopher and author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman since 2011. It chose Hambling for the sculpture unanimously. Hambling's design, features a figure – described as an everywoman – emerging out of organic matter. It is inspired by Wollstonecraft's claim to be “the first of a new genus”. Wollstonecraft's famous quotation, “I do not wish women to have power over men but over themselves.”, will appear on the plinth.[32] The statue is to be erected in Newington Green, north London, across from the Newington Green Unitarian Church, where Wollstonecraft worshipped.[33] Newington Green is known as the birthplace of feminism because of Wollstonecraft's roots there, and is where Wollstonecraft moved her school for girls from Islington in 1784.[34]

Awards

In 1995, she was awarded the Jerwood Painting Prize[35] (with Patrick Caulfield). In the same year she was awarded an OBE for her services to painting, followed by a CBE in 2010.

Personal life

Hambling described herself as "lesbionic" (her adjective).[36] She formed a relationship with a fellow artist,[37] Victoria (“Tory”) Dennistoun, from a family of horse racing jockeys and trainers,[38] who was married to John Lawrence (later Lord Oaksey), aristocrat and horse racing journalist. Lord and Lady Oaksey's "marriage broke up in unhappily public fashion in the mid-1980s".[39] Tory Lawrence and Hambling have been together ever since, living in a cottage near Saxmundham in Suffolk.[40] The house was left to Hambling by Lady Gwatkin ( Isolen Mary June Wilson), widow of Norman Gwatkin.

For the last year of the life of Henrietta Moraes, she and Hambling were in a relationship. The artists' model, Soho muse, and memoirist died in 1999 and Hambling produced a posthumous volume of charcoal portraits of her.[41]

She has an eclectic personality shown when she once showed up to another television show filming in dinner jackets, bow ties and a false moustache.[citation needed]

Hambling does not care for her critics' words and enjoys controversy as well as dividing opinions. She speaks her mind and did not let the words of others affect her work or her determination to create what she wants. She is a woman of her word and once said that she would not speak during a television show if she could not smoke. The camerawoman had stated she would not work with someone who did; Hambling stuck to her word and did not speak.[42]

Political views

Hambling gave up smoking in 2004 and was involved in the campaign against the total ban on smoking in public places in England which took effect on 1 July 2007. Speaking at a news conference at the House of Commons on 7 February 2007, she said: "I wholeheartedly support the campaign against a ban on smoking in public places. Just because I gave up at 59, other people may choose not to. There must be freedom of choice, something that is fast disappearing in this so-called free country."[43] She took up smoking again on her 65th birthday but only 'the ones that smell of toothpaste'.[40]

In August 2014, Hambling was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian opposing Scottish independence in the run-up to September's referendum on that issue.[44]

References

- ^ [s.n.] (31 October 2011). Hambling, Maggi. Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/benz/9780199773787.001.0001/acref-9780199773787-e-00300039. (subscription required). Accessed October 2018.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (3 November 2003). "A word in your shell-like: get that monstrosity off our beach". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ a b Bredin, Lucinda (18 May 2002). "A matter of life and death". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Rix, Juliet (24 March 2017). "Maggi Hambling: 'I am relieved for my grandchildren that they are non-existent'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Maggi Hambling biography". Tate Gallery. 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

- ^ Phaidon Editors (2019). Great women artists. Phaidon Press. p. 169. ISBN 0714878774.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Maggi Hambling (1945–), Painter". National Portrait Gallery. 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ^ [s.n.] (2003). Hambling, Maggi. Grove Art Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000036357. (subscription required). Accessed October 2018.

- ^ Clark, Alex (22 January 2006). "Hambling for the defence". Observer Review & Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Wimbledon College of Art: About Wimbledon: Alumni: Alumni List. University of the Arts London. Retrieved August 2013.

- ^ Foster, Alicia (2004). Tate Women Artistis. London: Tate Publishing. pp. 204–205. ISBN 1-85437-311-0.

- ^ Wrathall, Claire (13 October 2017). "Exploring the palliative power of art". howtospendit.ft.com. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Oscar Wilde Memorial Sculpture". Dublin City Council. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ a b "London's Wilde tribute". BBC. 30 November 1998. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Spencer, Charles (22 September 2009). "Maggi Hambling's sculptures I'd love to smash". Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Right of Reply: Jeremy Isaacs". The Independent. 3 December 1998.

- ^ Jackson, Kevin (10 January 2011). "Tom Lubbock obituary". the Guardian. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Lubbock, Tom (1 December 1998). "It's got to go". The Independent. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Ardagh, Philip (2007). Philip Ardagh's book of absolutely useless lists, absurd facts, lies, half-truths, thoughts, suggestions and musings for every day of the year. London: Macmillan Children's. p. 468. ISBN 9780230700505.

- ^ Jenkins, Terence (2016). The Most Dangerous Woman in Europe: (And Other Londoners). p. 17. ISBN 9781785893186.

- ^ Andrew Woodger (23 September 2009). Maggi Hambling's sea paintings & the Aldeburgh Scallop. BBC Suffolk. Accessed October 2018.

- ^ Hambling, Maggi (May 2010). "Making the Waves Crash: A Conversation with Maggi Hambling". Art Book Part 2. XVII.

- ^ "Scallop: a celebration of Benjamin Britten". OneSuffolk. Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

- ^ Salisbury 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Fontana 1994, pp. 88, 103.

- ^ Gutzwiller, K (1992). "The Nautilus, the Halycon, and Selenaia: Callimachus's Epigram 5 Pf.= 14 G.-P". Classical Antiquity. 11 (2). University of California Press: 194–209. doi:10.2307/25010972. JSTOR 25010972.

- ^ Johnson 1994, p. 230.

- ^ "Birth of Venus". artble.com. 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Hope B. Werness; line drawings by Joanne H. Benedict and Hope B. Werness; additional drawings by Tiffany Ramsay-Lozano and Scott (2003). The continuum encyclopedia of animal symbolism in art. New York: Continuum. p. 359. ISBN 9780826415257.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Willard & Owens 1997, p. 68.

- ^ "Marsh Award for Excellence in Public Sculpture". Marsh Christian Trust. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Slawson, Nicola (16 May 2018) "Maggi Hambling picked to create Mary Wollstonecraft statue", The Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2018

- ^ Tomalin, Claire (1992). The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft (rev. ed. 1992). London: Penguin Books. p. 60. ISBN 9780140167610.

- ^ Jacobs, Diane (2001). Her Own Woman: The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. London: Simon & Schuster. pp. 334. Page 38.

- ^ Lynn Barber (2 December 2007). A Life in Pictures, The Interview: Maggi Hambling. The Observer. Accessed October 2018.

- ^ "Maggi Hambling: 'I was put forward to paint the Queen Mother but the word came back saying I was a bit risky'". The Independent. 1 May 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ "Suffolk Artists". suffolkartists.co.uk. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Ginnie James". 23 February 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Lord Oaksey". 5 September 2012.

- ^ a b A Life in the Day: Maggi Hambling, artist | The Sunday Times Magazine. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ Berger, John (2001). The last 235 days. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 07475-5589-3.

- ^ Calkin, Jessamy (14 January 2017). "Meet Britain's most straight-talking and foul-mouthed artist, Maggi Hambling". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Opposition to total smoking ban widens". Forest – Freedom Organisation for the Right to Enjoy Smoking Tobacco. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2007.

- ^ "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories | Politics". The Guardian. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

External links

- 59 artworks by or after Maggi Hambling at the Art UK site

- 1945 births

- Living people

- People from Sudbury, Suffolk

- 20th-century English painters

- 21st-century English painters

- English women painters

- English women sculptors

- Lesbian artists

- English portrait painters

- LGBT people from England

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Alumni of Camberwell College of Arts

- Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art

- People educated at Amberfield School

- Academics of Wimbledon College of Arts

- 20th-century British sculptors

- 20th-century British women artists

- 21st-century British women artists

- People from Saxmundham

- Bisexual artists