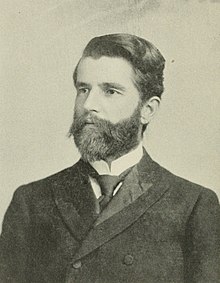

Marion Butler

Marion Butler | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from North Carolina | |

| In office March 4, 1895 – March 4, 1901 | |

| Preceded by | Matt W. Ransom |

| Succeeded by | Furnifold M. Simmons |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 20, 1863 Sampson County, North Carolina |

| Died | June 3, 1938 (aged 75) Takoma Park, Maryland |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Populist (previously a Democrat, later a Republican) |

| Spouse | Florence Faison Butler |

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina |

| Profession | Politician, Farmer, Lawyer, Editor, Publisher |

Marion Butler (May 20, 1863 – June 3, 1938) was a Populist U.S. senator from the state of North Carolina between 1895 and 1901 and brother of George Edwin Butler.

Early life

Butler was born in rural Sampson County, North Carolina during the American Civil War. He was a graduate of the University of North Carolina, where he was a member of the Philanthropic Literary Society. His goal of practicing law was not immediately realized due to his father's death, which forced Butler to take responsibility for managing the family farm in lieu of further education.

Farmers' Alliance and Populism

When the Farmers' Alliance movement spread from the Southwest into North Carolina in the late 1880s, he immediately joined the organization, and it provided him a ladder of political opportunity that he climbed with impressive speed. As the son of yeoman farmers, Butler grew up in a strong agrarian tradition. Possessing the formal education and literate articulateness provided from his years at the University of North Carolina, Butler stood out from his fellow farmers and, by the age of 25, was elected President of the local Farmers' Alliance and was elected President of the National Farmer's Alliance in 1893.[1]

Still a Democrat at this time, Butler was elected to the North Carolina Senate as an "Alliance Democrat" in 1890. In 1891, at age 28, he was elected President of the State Farmers' Alliance. Due to a general distaste for Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland, and the North Carolina Democratic Party's ruling that no voter could vote on a "split ticket", Butler led a mass exodus of Alliance members and followers from the Democratic party which had ruled the state since Reconstruction, to the Populist, or "People's Party" in 1892.[2]

During his tenure with the Populists, Butler was an advocate of "Fusion", meaning outright cooperation with the North Carolina Republican Party as a means to achieve some of the more important goals of his party. While some Populists disliked what they saw as a compromise made on some of their core beliefs, Butler saw short-term success, as the Populists and Republicans together polled a larger vote than the Democrats in the election of 1892, and swept both houses of the legislature in the Election of 1894.

Senate career

In 1894, Butler was elected as United States Senator from North Carolina, serving alongside Senator Jeter C. Pritchard.[2] As a United States Senator, Butler continued to advocate for workable reforms from the Populist Party Platform, including the regulation or outright ownership by the United States Government of railroads and telegraphs, as well as for a silver-based currency system.[3]

Butler obtained national prominence in the United States presidential election, 1896 when he orchestrated a compromise between Democrats and Populists. Populists endorsed Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan on a ticket with Populist vice-presidential nominee Thomas E. Watson. This was another example of "fusion" under Butler. Ironically, this national Populist-Democrat cooperation coincided with the Populist-Republican cooperation in North Carolina.[1] After Bryan's loss, Butler continued to work for reform on the national stage which would benefit farmers, but this work would soon be cut short by the "white supremacy" campaigns of the Democratic Party in North Carolina. Butler lost his bid for re-election in 1900, however he would remain the national chairman of the People's Party until 1904 when he would officially become a Republican. Butler joined the Progressive Republican Faction of the National Republican Party alongside notable individuals such as Theodore Roosevelt. [4]

Post–Senate career

During his time as Senator, Butler received his law degree from the University of North Carolina, and after his electoral defeat in 1904, practiced law in Washington, D.C.[1][3]

He had married Florence Faison of Sampson County on August 31, 1893, and they had five children: Pocahontas, Marion, Edward F., Florence F., and Wiley.[1] The former Senator died in Takoma Park, Maryland in 1938, and was buried at Saint Paul's Episcopal Church in Clinton, North Carolina.[5] A portrait of Marion Butler during his time in the U.S. Senate is included in the collection of the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies in their chambers on the campus of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Legacy

Butler's legacy is surrounded by considerable debate among scholars of the era. Progressive historians, who tend to look favorably on the goals of the Populist Movement in general have often discarded Butler's fusionism, silver-backed currency and emphasis on white supremacy as being "un-Populist".[6] In refuting this analysis, some historians point to Butler's immense popularity among Populist adherents, and to the fact that Butler held at different times the Presidency of the National Farmers' Alliance and was Chairman of the Populist Party itself.[7]

Regardless of the classification of Butler's beliefs and actions, it is undisputed that his actions and rhetoric were extremely influential in the North Carolina and national Populist movement, especially after the death of Leonidas L. Polk, the movement's elder statesman, in 1892.

The Marion Butler Birthplace was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.[8]

References

- William S. Powell, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography (1979)

- James L. Hunt, Marion Butler and American Populism (2003)

- James M. Beeby, Revolt of the Tar Heels: The North Carolina Populist Movement, 1890–1901 (2008)

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Durden, Robert F. "Marion Butler, 1863–1938". docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved 2015-05-12. Cite error: The named reference "durden" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b James L. Hunt, Marion Butler and American Populism (2003)

- ^ a b Powell, supra.

- ^ http://www.designhammer.com, Website. "North Carolina History Project : Marion Butler (1863–1938)". www.northcarolinahistory.org. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

{{cite web}}: External link in|last= - ^ Hunt, supra.

- ^ Hunt, supra pp. 2–4

- ^ Hunt, supra pp. 6–7

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

External links

- United States Congress. "Marion Butler (id: B001183)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- North Carolina Election of 1898

- Addresses of Marion Butler, President, and Cyrus Thompson, Lecturer, to the North Carolina Farmers' State Alliance, at Greensboro, N.C., Aug. 8, 9, and 10, 1893, at its Seventh Annual Session.