Masinissa

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2012) |

| Masinissa | |

|---|---|

| King of Numidia | |

| |

| King of Numidia | |

| Reign | 202 BC-148 BC |

| Predecessor | New establishment |

| Successor | Micipsa |

| King of the Massylii | |

| Reign | 206 BC-202 BC |

| Predecessor | Lacumazes |

| Successor | Himself as King of Numidia |

| Born | c. 238 BC |

| Died | c. 148 BC (aged 90) |

| Burial | |

| Issue | Micipsa Gulussa Mastanabal |

| Father | Gala |

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

Masinissa, or Masensen, (Berber: Masnsen, ⵎⵙⵏⵙⵏ; c.238 BC[1] – c. 148 BC) — also spelled Massinissa and Massena — was the first King of Numidia. During his younger years he fought in the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), first against the Romans as an ally of Carthage and later switching sides. With Roman support, he united the eastern and western Numidian tribes and founded the Kingdom of Numidia. He is most famous for his role as a Roman ally in the Battle of Zama and as husband of Sophonisba, a Carthaginian noblewoman whom he allowed to poison herself to avoid being paraded in a triumph in Rome.

His name was found in his tomb of Cirta, modern-day Constantine in Algeria under the form of MSNSN (which has to be read as Mas'n'sen which means "Their Lord").

Masinissa is largely viewed as an icon and an important forefather among modern Berbers.

Masinissa's story is told in Livy's Ab Urbe Condita (written c. 27–25 BC). He is also featured in Cicero's Scipio's Dream.

Biography

Early life

Masinissa was the son of the chieftain Gala of a Numidian tribal group, the Massylii. He was brought up in Carthage, an ally of his father. At the start of the Second Punic War, Masinissa fought for Carthage against Syphax, the king of the Masaesyli of western Numidia (present day Algeria), who had allied himself with the Romans. Masinissa, then 17 years old, led an army of Numidian troops and Carthaginian auxiliaries against Syphax's army and won a decisive victory.

After his victory over Syphax, Masinissa commanded his skilled Numidian cavalry against the Romans in Spain, where he was involved in the Carthaginian victories of Castulo and Ilorca in 211 BC. After Hasdrubal Barca departed for Italy, Masinissa was placed in command of all the Carthaginian cavalry in Spain, where he fought a successful guerrilla campaign against the Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio (Scipio Africanus) throughout 208 and 207, while Mago Barca and Hasdrubal Gisgo levied and trained new forces. In 206, with fresh reinforcements, Mago and Hasdrubal Gisgo — supported by Masinissa's Numidian cavalry — met Scipio at the Battle of Ilipa, where Carthage's power over Hispania was forever broken in arguably Scipio Africanus's most brilliant victory.

When Gala died in 206, his son Masinissa and his brother Oezalces quarreled about the inheritance, and Syphax — now an ally of Carthage — was able to conquer considerable parts of the eastern Numidia. Meanwhile, with the Carthaginians having been driven from Hispania, Masinissa concluded that Rome was winning the war against Carthage and therefore decided to defect to Rome. He promised to assist Scipio in the invasion of Carthaginian territory in Africa. This decision was aided by the move by Scipio Africanus to free Masinissa's nephew, Massiva, whom the Romans had captured when he had disobeyed his uncle and ridden into battle. Having lost the alliance with Masinissa, Hasdrubal started to look for another ally, which he found in Syphax, who married Sophonisba, Hasdrubal's daughter who until the defection had been betrothed to Masinissa. The Romans supported Masinissa's claim to the Numidian throne against Syphax, who was nevertheless successful in driving Masinissa from power until Scipio invaded Africa in 204. Masinissa joined the Roman forces and participated in the victorious Battle of the Great Plains (203), after which Syphax was captured.

At the Battle of Bagbrades (203), Scipio overcame Hasdrubal and Syphax and while the Roman general concentrated on Carthage, Gaius Laelius and Masinissa followed Syphax to Cirta, where he was captured and handed over to Scipio. After the defeat of Syphax, Masinissa married Syphax's wife Sophonisba, but Scipio, suspicious of her loyalty, demanded that she be taken to Rome and appear in the triumphal parade. To save her from such humiliation, Masinissa sent her poison, with which she killed herself. Masinissa was now accepted as a loyal ally of Rome, and was confirmed by Scipio as the king of the Massylii.

At the Battle of Zama Masinissa commanded the cavalry (6,000 Numidian and 3,000 Roman) on Scipio's right wing, Scipio delayed the engagement for long enough to allow for Masinissa to join him. With the battle hanging in the balance, Masinissa's cavalry, having driven the fleeing Carthaginian horsemen away, returned and immediately fell onto the rear of the Carthaginian lines. This decided the battle and at once Hannibal's army began to collapse. The Second Punic War was over and for his services Masinissa received the kingdom of Syphax, and became king of Numidia.

Masinissa was now king of both the Massylii and the Masaesyli. He showed unconditional loyalty to Rome, and his position in Africa was strengthened by a clause in the peace treaty of 201 between Rome and Carthage prohibiting the latter from going to war even in self-defense without Roman permission. This enabled Masinissa to encroach on the remaining Carthaginian territory as long as he judged that Rome wished to see Carthage further weakened.

Later life

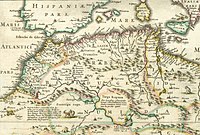

With Roman backing, Masinissa established his own kingdom of Numidia, west of Carthage, with Cirta — present day Constantine — as its capital city. All of this happened in accordance with Roman interest, as they wanted to give Carthage more problems with its neighbours. Masinissa’s chief aim was to build a strong and unified state from the semi-nomadic Numidian tribes. To that end, he introduced Carthaginian agricultural techniques and forced many Numidians to settle as peasant farmers. Masinissa and his sons possessed large estates throughout Numidia, to the extent that Roman authors attributed to him, quite falsely, the sedentarization of the Numidians. Major towns included Capsa, Thugga (modern Dougga), Bulla Regia and Hippo Regius.

All through his reign, Masinissa extended his territory, and he was cooperating with Rome when, towards the end of his life, he provoked Carthage to go to war against him. Any hopes he may have had of extending his rule right across North Africa were dashed, however, when a Roman commission headed by the elderly Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Elder) came to Africa about 155 BC to decide a territorial dispute between Masinissa and Carthage. Animated probably by an irrational fear of a Carthaginian revival, but possibly by suspicion of Masinissa’s ambitions, Cato thenceforward advocated, finally with success, the destruction of Carthage. Based on descriptions from Livy, the Numidians began raiding around seventy towns in the southern and western sections of Carthage's remaining territory. Outraged with their conduct, Carthage went to war against them, in defiance of the Roman treaty forbidding them to make war on anyone, thus precipitating the Third Punic War (149–146 BC). Masinissa showed his displeasure when the Roman army arrived in Africa in 149 BC, but he died early in 148 BC without a breach in the alliance. Ancient accounts suggest Masinissa lived beyond the age of 90 and was apparently still personally leading the armies of his kingdom when he died.

After his death, Numidia was divided into several smaller kingdoms ruled by his sons. His descendants were the elder Juba I of Numidia (85 BC–46 BC) and younger Juba II (52 BC–AD 24).

In literature, art and film

- Africa (late 1330s), an epic poem by Petrarch

- Sophonisbe (1680), a German mourning play by Daniel Casper von Lohenstein

- Cabiria (1914), classic Italian silent film directed by Giovanni Pastrone. Masinissa is portrayed by Vitale Di Stefano.

- Pride of Carthage (2005), a novel by David Anthony Durham

-

Scipio at the deathbed of Masinissa

-

Central wall depicting Sophonisba requesting help from Massinissa

See also

References

- ^ Fage, J. D. (1979-02-01). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780521215923.

- Livy (trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt) (1965). The War With Hannibal. New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044145-X