Milton Blockhouse

| Milton Blockhouse | |

|---|---|

| Gravesend, Kent | |

| Type | Device Fort |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Destroyed |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Stone and brick |

Milton Blockhouse was an artillery fortification constructed as part of Henry VIII's Device plan of 1539, in response to fears of an imminent invasion of England. It was built at Milton, near Gravesend in Kent at a strategic point along the River Thames, and was operational by 1540. Equipped with 30 pieces of artillery and a garrison of 12 men and a captain, it was probably a two-storey, D-shaped building, designed to prevent enemy ships from progressing further up the river or landing an invasion force. It was stripped of its artillery in 1553 and was demolished between 1557 and 1558; nothing remains of the building above ground, although archaeological investigations in the 1970s uncovered parts of the blockhouse's foundations.

Background

Milton Blockhouse was built as a consequence of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire in the final years of the reign of King Henry VIII. Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to the local lords and communities, playing only a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications, and while France and the Empire remained in conflict with one another, maritime raids were common but an actual invasion of England seemed unlikely.[1] Modest defences, based around simple blockhouses and towers, existed in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, as well as a few more impressive works in the north of England, but in general the fortifications were very limited in scale.[2]

In 1533, Henry broke with Pope Paul III in order to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and remarry.[3] Catherine was the aunt of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, and he took the annulment as a personal insult.[4] This resulted in France and the Empire declaring an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraging the two countries to attack England.[5] An invasion of England now appeared certain.[6]

Device of 1539

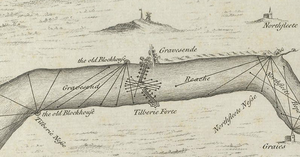

Henry issued an order, called a "device", in 1539, giving instructions for the "defence of the realm in time of invasion" and the construction of forts along the English coastline.[7] Under this programme of work the River Thames was protected by a mutually reinforcing network of blockhouses at Gravesend, Milton, and Higham on the south side of the river, and Tilbury and East Tilbury on the opposite bank.[8]

The fortifications were strategically placed. London and the newly constructed royal dockyards of Deptford and Woolwich were vulnerable to seaborne attacks arriving up the Thames estuary, which was then a major maritime route; 80 percent of England's exports passed through it.[9] The village of Milton and the adjacent town of Gravesend, only 500 metres (1,600 ft) apart, formed a particularly important communications point along the river.[10] They formed the centre of the "Long Ferry" traffic of passengers into the capital, and for the "Cross Ferry" over the river to Tilbury, resulting in the local riverbank becoming lined with wharfs.[11] This was also the first point that an invasion force would be able to easily disembark along the Thames, as before this point the mudflats along the sides of the estuary would have made landings difficult.[12]

Construction

Milton Blockhouse was designed by the Clerk of the King's Works, James Nedeham, and the Master of Ordnance, Christopher Morice, with Robert Lorde serving as the paymaster for the project and Lionel Martin, John Ganyn and Mr Travers acting as the local overseers.[13] The fort was built on Chapel Field, which the Crown bought, along with the land for Gravesend Blockhouse, from William Burston for £66; the field had previously been part of Milton Chantry, dissolved by Henry VIII during the Reformation.[14][a] The work was quickly completed, and by 1540 the blockhouse was in operation and equipped with 30 artillery guns, 6 handguns and various pikes and longbows.[13] Initially commanded by Captain Sir Edward Cobham, it had a small garrison of 12 men, including a second in command, a porter, three soldiers and seven gunners; these men would have been supported by reinforcements if the fort had ever come under attack.[16]

Fresh fears of invasion after 1544 prompted further work being carried out on the blockhouse by Sir Richard Lee, a prominent military engineer, although peace was declared the following year.[17] It is uncertain exactly what shape the fort took; archaeological investigations suggest that it was probably D-shaped, two storeys tall, with a circular bastion facing the river; there would have been battery positions on either side of the main defences, and a more modern, angular bastion was added later on the landwards side.[18] By 1546 the King's accountants estimated that £1,072 had been spent on building and developing the fortification.[19][a]

Destruction

In 1553, orders were issued for the artillery pieces to be removed from the blockhouse and taken to the Tower of London; the fort was then demolished between 1557 and 1558, the brick and stone from the site being reused to repair the Tower.[20] The former site was probably rediscovered during excavations in 1826, but was destroyed during the building of the Gravesend Canal Basin, Canal Road and the Gordon Pleasure Gardens later in the 19th century.[21] Archaeological investigations between 1973 and 1978 uncovered the foundations of the blockhouse, now protected under UK law as a scheduled monument.[22]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Comparing 16th century costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £66 in 1539 could be equivalent to between £37,200 and £16,940,000 in 2014 terms, depending on the price comparison used, and £1,072 in 1546 to between £403,800 and £184,200,000. For comparison, the total royal expenditure on all the Device Forts across England between 1539–47 came to £376,500, with St Mawes, for example, costing £5,018, and Sandgate £5,584.[15]

References

- ^ Thompson 1987, p. 111; Hale 1983, p. 63

- ^ King 1991, pp. 176–177

- ^ Morley 1976, p. 7

- ^ Hale 1983, p. 63; Harrington 2007, p. 5

- ^ Morley 1976, p. 7; Hale 1983, pp. 63–64

- ^ Hale 1983, p. 66; Harrington 2007, p. 6

- ^ Harrington 2007, p. 11; Walton 2010, p. 70

- ^ Harrington 2007, p. 20

- ^ Smith 1980, p. 342; Saunders 1989, p. 42

- ^ Saunders 1989, p. 42; Harrington 2007, p. 28; Kent Council 2004, p. 8

- ^ Saunders 1989, p. 42; Kent Council 2004, p. 8

- ^ Smith 1974, p. 142

- ^ a b Smith 1980, p. 344

- ^ Smith 1980, p. 344; "Milton Chantry", Historic England, retrieved 13 May 2015

- ^ Biddle et al. 2001, p. 12; Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 29 May 2015

- ^ Smith 1980, p. 344; Smith 1974, p. 146

- ^ Smith 1980, pp. 345–346

- ^ Smith 1980, pp. 349, 357–358; Smith 1974, p. 143

- ^ Smith 1980, p. 346

- ^ Smith 1980, p. 347; Smith 1974, p. 148

- ^ Smith 1980, pp. 348–349

- ^ Smith 1980, p. 349

Bibliography

- Biddle, Martin; Hiller, Jonathon; Scott, Ian; Streeten, Anthony (2001). Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. ISBN 0904220230.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hale, J. R. (1983). Renaissance War Studies. London, UK: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0907628176.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harrington, Peter (2007). The Castles of Henry VIII. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472803801.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kent Council (2004). Gravesend – Kent, Archaeological Assessment Document. Maidstone, UK: Kent Council and English Heritage.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Routledge Press. ISBN 9780415003506.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morley, B. M. (1976). Henry VIII and the Development of Coastal Defence. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0116707771.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saunders, Andrew (1989). Fortress Britain: Artillery Fortifications in the British Isles and Ireland. Liphook, UK: Beaufort. ISBN 1855120003.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Victor T. C. (1974). "The Artillery Defences at Gravesend". Archaeologia Cantiana. 89: 141–168.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Victor T. C. (1980). "The Milton Blockhouse, Gravesend: Research and Excavation". Archaeologia Cantiana. 96: 341–362.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, M. W. (1987). The Decline of the Castle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1854226088.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walton, Steven A. (2010). "State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortification". Osiris. 25 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1086/657263.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)