Miriam Ben-Porat

Miriam Ben-Porat | |

|---|---|

| מרים בן פורת | |

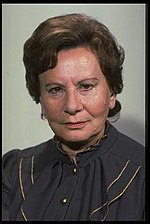

Miriam Ben-Porat in 1983 | |

| Born | Miriam Shinezon April 26, 1918 |

| Died | July 26, 2012 (aged 94) |

| Citizenship | Israeli |

| Alma mater | Hebrew University of Jerusalem |

| Occupation(s) | Supreme Court of Israel judge; State Comptroller of Israel |

| Children | 1 |

| Awards |

|

Miriam Ben-Porat (Template:Lang-he, née Shinezon, 26 April 1918 – 26 July 2012) was an Israeli jurist. She was the first female appointed to the Supreme Court of Israel and the State Comptroller of Israel from 1988-1998.[1]

Early life and education

Shinezon was born in 1918 in Vitebsk, Belarus (then Russia), the youngest of three sisters and four brothers. She grew up in Lithuania, where her parents owned a textile factory. After finishing high school in 1936, she immigrated to the British Mandate of Palestine by herself.

Most of her family was killed in the Holocaust. In the Yishuv, she changed her name to Ben-Porat. She was one of the first women to study law at the Hebrew University, and in 1945 she was admitted to the bar.[2]

Judicial career

In 1949 she began to work in the State Attorney's office, and by 1953 she became the deputy State Attorney. In 1959 she was appointed as a judge in the Jerusalem District Court. Her swearing-in ceremony was boycotted by the Israeli Bar Association. Only following a public scandal, an apology was arranged between her and the Jerusalem Chamber of Advocates.

By 1975, she became the President of the Jerusalem District Court. From 1964 through 1978, she was also a professor at the Hebrew University, specializing in contracts and commercial notes. She was the only faculty member without a doctorate.[3]

She was a very sensitive Judge, doing her best to find human solutions in hard Judicial cases, she had an equal attitude towards young and well known advocates, honored and respected al those who appeared in her court and admired honesty.

In 1977, she became the first woman appointed to the Supreme Court.[4][5] In 1988, upon reaching the retirement age for judges, she was elected by the Knesset to be the State Comptroller. She was the first woman to serve in this position.[2] After five years, she was reelected.[4]

State Comptroller

In 1990, she published a report on the Israeli water system, which led to the dismissal of the water commissioner;[6] A report saying the government didn't make the proper arrangements to absorb immigrants from the former Soviet Union;[6] A criticism of the investigation of policemen by the police, which led to the establishment of the police investigation unit in the Justice Ministry.[7]

In 1991, she exposed the funds transfer by Minister of Interior Aryeh Deri to Shas institutions, which led to his trial. She also reported shortcomings in Israel's preparations to the Gulf War. She stopped a deal planned by Housing Minister Ariel Sharon to purchase 20,000 apartments from one contractor company.[8] In 1992 she criticized the Housing Ministry, leading to the firing and indictment of Amidar chairman of the board, Uri Shani. In 1993, the law of government companies was amended following a report she published in 1989. She also managed to postpone a plan proposed by Finance Minister Avraham Shohat to sell Bank Hapoalim shares.[9] In 1994 she pointed out suspicions of Housing Minister Binyamin Ben-Eliezer's commitments to transfer funds to local authorities affiliated with the Labour Party.[7][10]

In 1995, she assailed the Shin Bet for breaching the Landau Commission report on torture.[11] A criminal investigation was opened against major figures in the Ministry of Religious affairs, based on her report.[12] She also led to the amendment of the arrest law. In 1996 she revealed that the Transportation Minister Israel Kessar had allotted funds to local authorities, preferring authorities whose heads are Labour Party members. In 1997 she criticized the government's handling of the Israel Dockyards company during the time in which the company was in a state of temporary liquidation.[7]

On July 4, 1998, at the end of two terms, she retired from her position as State Comptroller, although she stayed involved in public activity and writing.[7][13]

Awards and honors

- In 1995, Ben-Porat received a prize from the Movement for Quality Government in Israel.[7]

- On April 18, 1991, she was awarded the Israel Prize for her special contribution to society and the State of Israel.[2][13][14]

- On May 17, 1993, she received an honorary doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania.

- In September 2000, she was given an honorary doctorate from Hebrew Union College.

- In 2004, she received the Yakir Yerushalayim (Worthy Citizen of Jerusalem) award from the city of Jerusalem.[15]

References

- ^ "Prof. Miriam Ben-Porat dead at 94". July 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c Salokar and Volcansek (1996), p. 38

- ^ Salokar and Volcansek (1996), p. 39

- ^ a b Salokar and Volcansek (1996), p. 38, 40

- ^ Edelman (1994), p. 39

- ^ a b Brinkley, Joel (29 August 1991). "Israeli Civic Watchdog is Suddenly a Target". New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Ben-Porat Miriam" (in Hebrew). 3 July 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ Haberman, Clyde (April 29, 1992). "Likud Is Set Back by a Report of Waste and Graft". New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ "Comptroller stops Hapoalim sale". Israel Business Today. March 5, 1993. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ Gordon, Evelyn (May 22, 1996). "Ben-Eliezer should have been indicted". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ "Israel admits torture". BBC. February 9, 2000. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ Perry and Ironside (1999), p. 158

- ^ a b "Miriam Ben-Porat". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. January 8, 2001. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Israel Prize Official Site – Recipients in 1991 (in Hebrew)".

- ^ "Recipients of Yakir Yerushalayim award (in Hebrew)". City of Jerusalem official website

Further reading

- Edelman, Martin (1994). Courts, Politics, and Culture in Israel. University of Virginia Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-8139-1507-4.

- Perry, Dan; Alfred Ironside (1999). Israel and the quest for permanence. McFarland. p. 216. ISBN 0-7864-0645-3.

- Salokar, Rebecca Mae; Mary L. Volcansek (1996). Women in Law: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 376. ISBN 0-313-29410-0.

See also

- 1918 births

- 2012 deaths

- Belarusian Jews

- Israel Prize for special contribution to society and the State recipients

- Israel Prize women recipients

- Israeli jurists

- Israeli people of Belarusian-Jewish descent

- Israeli women judges

- Hebrew University of Jerusalem alumni

- Judges of the Supreme Court of Israel

- People from Vitebsk

- State Comptrollers of Israel

- Soviet emigrants to Mandatory Palestine