Narquois (racehorse)

| Narquois | |

|---|---|

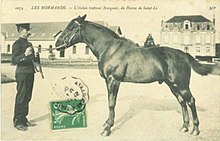

Narquois, photographed by Delton Studio. | |

| Sire | Fuschia |

| Dam | Hébé III |

| Sex | Male |

| Foaled | Urgent, Beaumanoir, Barcarolle, Chrisis, and Hermione V Secqueville-en-Bessin |

| Died | 1911 |

| Color | Seal brown |

Narquois (born 1891, died 16 August 1911) was a racehorse born in Calvados, an Anglo-Norman trotter. He was one of the first sons of the main stallion behind the French Trotter, the head of the Fuschia breed. Like him, Narquois became an excellent competitor, but at the same time was renowned for his ugliness. He usually competed in pairs with his half-sister, the mare Nitouche.

In 1895, he lowered the French trotting mile record to 1' 29'' 75, and also set the European speed record over 3,200 meters. Acquired by the Haras Nationaux, he was put to stud at the Haras National de Saint-Lô until 1911, when he was slaughtered. Such was his success with breeders that specific conditions of access to breeding had to be established. Narquois sired 255 trotters, including Beaumanoir. He sired two branches of the Conquérant family, which are still very much alive in the French Trotter breed.

A Group 3 harnessed trotting race is named "Prix Narquois" in tribute to him.

History[edit]

Narquois was born in 1891[1] in Secqueville-en-Bessin, Calvados, to breeders M. du Rozier[2] and Vaulogé.[3] He was trained by Lemoine[3] (casaque rose).[4]

He excelled in racing, earning 92,246 francs over two years of competition, a considerable sum in his day.[5][6] In April 1894, the Grand Prix d'Essai, the traditional first classic of each generation, seemed destined for Neuilly, another son of Fuschia.[7] Narquois won easily, 6 seconds ahead of Nodus.[8] However, he was beaten twice in the following days by the winner of the Prix Bayadère[8] (equivalent to the Prix d'Essai for fillies), Narcisse: first on 4 April at Maisons-Laffitte,[9] then on 22 April at Vire.[10] In July, Narquois clocked the fastest time for a three-year-old colt over 4,000 meters at Vincennes, 1' 36'' 1/10,[3] in the Critérium des 3 ans ridden trotting race.[11] He frequently ran with his half-sister Nitouche, from the same stable and sire, who was "sacrificed" to him, but the latter was initially considered better than him.[4] He made his comeback for the 1895 racing season in the Prix Conquérant on 1 April, which he won in 1' 38'' 1/6.[4]

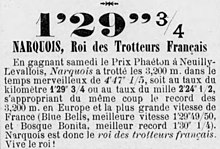

French and European record in the Prix Phaéton of 1895[edit]

In May 1895, when Narquois was entered in the Prix Phaéton, a 3,200-meter race at the Neuilly-Levallois racecourse, he initially attracted little attention, as the mare Odessa was considered better served by the race conditions (the 3-year-olds had a 75-meter lead[12]) and had won a race over the same distance in 1' 34''.[4] No French Trotter has yet reached 1' 30".[4] Narquois completed his first lap in a record time of 1' 27''. His stablemate Nitouche came second, with a mile reduction of 1' 31'' 5/16. Odessa finished third.[4] Narquois completed the race in 4' 47''.[13] He achieved a kilometer reduction of 1' 29'' 3/4.[14][15]

Alban d'Hauthuille, in his study Les courses de chevaux published in 1982 in the PUF Que sais-je? collection, mentioned Narquois as one of the trotters who broke the kilometer record at the beginning of the French Trotter breed's history,[16] along with other renowned hippologists such as Louis Cauchois[17] and Paul Diffloth.[18] This constituted the record over 3,200 meters at European level, as well as the French record in kilometer reduction, as quoted and then approved in La France chevaline[3] and the Revue des Haras.[13]

Narquois was described as the "king of French Trotters".[4]

Continuation of the 1895 season[edit]

Later in the season, Narquois raced at Saint-Lô, where he broke the French record over 4,000 meters at mounted trotting, beating Messagère in 6' 16'' 2/5. He returned to Levallois and set the French record over 4,200 meters, in 6' 30'' 2/5,[4] ahead of his stablemate Nitouche.[4] He took part in the Rouen racecourse derby over 3,200 meters, beating Novice and Napoléon in 4' 38'' 1/2.[4] He continued his season at Dieppe, racing over 4,000 meters in 6' 22''.[4]

This was followed by another victory in the Prix du Conseil général at Caen, ahead of Hallali and Niemen.[4] Narquois's reputation was excellent at the time, so much so that his defeat the following day at the Cabourg racecourse after a poor start against Novice, Marin and Messagère came as a nasty surprise, suggesting overwork.[4] Narquois made up for it in his next race at Lisieux, winning the Prix de Quatre Ans against Nymphe, Niemen and Nitouche.[4]

Four days later, Narquois returned to Levallois and beat his own record over 4,200 meters, in 6' 21'', a speed never before achieved over this distance in mounted trotting.[4] Narquois having beaten all the trotters of his generation, a match was proposed against the mare Ergoline, whose last race was the Prix Zéthus.[4] Narquois missed his start, lose 100 meters, made two mistakes, and never catched up with his rival.[4]

Narquois then went on to the prize of the Haras national du Pin, which he won in 1' 34'' 3/10 ahead of Novice and Néri, before winning the Prix de l'Administration des Haras at Caen, ahead of Néri and Nestorius.[4] He returned to Levallois on 2 October, with the young mare Obole as his main rival, but missed his start, while Obole collapsed on the third lap.[4] He ended his season on 7 October in the Prix de la Marne at Vincennes, which he won easily in 1' 37", ahead of all the other 4-year-old trotters.[4]

At stud[edit]

His performances earned him a purchase by the Haras Nationaux, for the hefty sum of 30,000 francs (according to the 1909 memoirs of the Académie des Sciences, Arts et Belles-Lettres de Caen),[19] 34,000 francs (according to La France chevaline,[4] the Caen veterinarian Alfred Gallier[5] and Pierre de Choin,[20] information taken up by Jean-Pierre Reynaldo[6]) or 35,000 francs (according to La Revue hebdomadaire of 1906).[21] At the time, this was the record purchase price for a trotter by the French state.[4]

He was awarded to the haras national de Saint-Lô,[6] which stationed him at Sainte-Marie-du-Mont from 1896 to 1911.[22][23][24] His success as a stallion proved so great that special conditions of access to covering had to be established: only mares with a mileage reduction of 1' 42" were authorized to receive Narquois.[25] In 1900, the stud fee was around 50 francs.[26] In 1901, he was one of the top ten trotting stallions on the breeding list, ranking 8th, well behind the top stallion on the list, who was also his sire, Fuschia, as well as stallions Harley and James Watt.[27]

Along with Harley, he was the most famous stallion at the haras national de Saint-Lô in his day.[28] Narquois became less sought-after over time, with 159 registrations in 1908 for a covering at the haras national de Saint-Lô, compared with 177 in 1907.[29] In 1910, he reached third place in the list of leading trotting stallions.[30]

His death, dated 16 August 1911, was announced in the newspaper La France chevaline of August 19[31]:

"Narquois was slaughtered on the spot, because of his excellent services [...]. The State, as a horse owner, must behave as gallantly as an ordinary horse owner, who would not send an old servant to the Parisian slaughterhouses to collect a tiny sum [...].[32]

Description[edit]

For Plagny breeder Édouard Nicard, Narquois had the appearance of a Norfolk Trotter, and was strongly reminiscent of his maternal grandfather the stallion Niger[33] in his "square" appearance.[34] He was particularly muscular, with strong, high-quality legs.[24]

Like his sire Fuschia, he was renowned for his ugliness,[6] having inherited his "ugly head grafted onto a too-short neck".[35] Breeder Maurice de Gasté described a "deformity" in trotting stallions such as Narquois, which makes them unsuitable for the saddle: the shoulder is straight, short and forward; the neck is high, long underneath, short above, and extremely powerful; the head attachment is thick, with developed maxillae and a strong head; the rump is powerful and strongly sloping.[36]

The coat was seal brown.[37]

Origins and lineage[edit]

Narquois was sired by the stallion Fuschia and the mare Hébé III, by Niger.[5][14][38] According to an article published in La Quinzaine littéraire, he was considered one of the best sons of Fuschia, along with Messagère, Moonlighter, Novice, and Hérode;[35] A. Ollivier cites Portici, Hetmann, Narquois, Mars and Novice.[39] His origins are marked by the Norfolk Trotter, represented by Niger, and the Thoroughbred.[40] The calculation of known Thoroughbred origins showed 44.8% Thoroughbred origins.[41]

Édouard Nicard reported that, at the time of Narquois' success on the racecourse, a newspaper subsidized by American funds claimed American paternity for this stallion: "This one, at least, we can claim highly as an American, both by the sire and the dam. On the father's side we find Miss Pierce, daughter of Lady Pierce, an American. On his mother's side we find the American Miss Bell. It's thanks to this double stream of trotter blood that he can triumph over Anglo-Norman horses".[42] The Miss Bell mare is, however, described as English (probably largely Thoroughbred) by Nicard, who regrets that her origins are unknown.[33]

The Thoroughbred mare Débutante, dam of Bank Note, seemed to have had a positive influence on her entire lineage.[43] She was out of the stallion Pretty Boy.[44]

| Sire Fuschia (1883–1908) |

Reynolds (1873) | Conquérant (1858–1880) | Kapirat (1844–1870) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Élisa (1853–1881) | |||

| Miss Pierce (1857) | Succès (1852) | ||

| Lady Pierce (1850) | |||

| Rêveuse (1878) | Lavater (1867–1887) | Crocus (1858) | |

| Candelaria | |||

| Sympathie (1862) | Pédagogue (1854) | ||

| Débutante (1855–1867) | |||

| Dam Hébé III (1885) |

Niger (1869–1891) | The Norfolk Phœnomenon (1845–1872) | The Norfolk Phenomenon (1824) |

| No info | |||

| Miss Bell (1857) | No info | ||

| No info | |||

| Bank Note (1879) | Normand (1869–1883) | Divus (1859) | |

| Balsamine (1857) | |||

| Débutante (1855–1867) | No info | ||

| No info |

Descendants[edit]

Narquois sired 255 trotters. Beaumanoir became his most famous son,[6] but other descendants reduced the trotting speed record: Custer trotted the kilometer in 1' 25", and Arthur in 1' 26".[20] His son Custer (b. 1902) won the 1911 European championship in harness racing.[45]

Narquois is cited by M. P. Guillerot and Count Marie-Aimery de Comminges as one of the first true trotting stallions capable of sustaining a trotting breed on its own, without resorting to crossbreeding with Thoroughbreds.[46]

A son of Narquois or Beaumanoir and out of a dam by Cherbourg, the Grand Maître stallion owned by Mr. Lallouet won the first trotter stallion prize in 1910.[47] In 1909, his earnings totaled 46,325 francs from three public appearances.[47] According to Louis Baume, in 1913, Narquois' foals sold, on average, for between 2,500 and 4,000 francs, as much as Harley's, but less than Fuschia's.[48]

In 1929, it was said that Narquois "figured in the pedigree of that time's best horses".[49]

Placement in the lineage of Conquérant[edit]

In 1902, when A. Ollivier drew up his Généalogies chevalines anglo-normandes en ligne mâle, he placed Narquois in the Conquérant branch, in the lineage of the English stallion Young Rattler.[50] Jean-Pierre Reynaldo drew up a more recent classification of the surviving lineages of the French Trotter, and attributed Narquois a presence in two branches descended from the Conquérant branch, branch "e" and branch "f".[51] According to Reynaldo, branch "e" was still very much alive in 2015.[52]

| Young Rattler (1811) | ||

| Impérieux (1822) | ||

| Voltaire (1833) | ||

| Kapirat (1844) | ||

| Conquérant (1858) | ||

| Reynolds (1873) | ||

| Fuschia (1883) | ||

| Narquois (1891) | ||

| Urgent (1898) | Custer (1902) | Beaumanoir (1901) |

| Kœnigsberg (1910) | ||

| Boléro (1923) | ||

| Loudéac (1933) | ||

| Fandango (1944) | ||

Tributes[edit]

A mounted trotting race run at Vincennes in 1922 was named "Prix Narquois" in his honor.[54] The race is still held in the 21st century, and has become a Group 3 in harness racing. It is run in December.[55]

References[edit]

- ^ "Narquois". www.letrot.com (in French). Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Reynaldo (2015, p. 88-89)

- ^ a b c d La France chevaline du 15 mai 1895 [La France chevaline, May 15, 1895] (in French). Gallica.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Revue des courses au trot en 1895 [Review of trotting races in 1895] (in French). La France chevaline.

- ^ a b c Gallier (1900, p. 160)

- ^ a b c d e Reynaldo (2015, p. 89)

- ^ Courses au trot de Paris-Vincennes [Paris-Vincennes trotting races] (in French). La France chevaline.

- ^ a b Comptes-rendus – Courses au trot de Paris-Vincennes [Reviews – Paris-Vincennes trotting races] (in French). La France chevaline.

- ^ Courses au trot de Maisons-Laffitte [Maisons-Laffitte trotting races] (in French). La France chevaline.

- ^ Courses de Vire [Vire races] (in French). La France chevaline.

- ^ Comptes-rendus – Courses au trot de Paris-Vincennes [Reviews – Paris-Vincennes trotting races] (in French). La France chevaline.

- ^ La France chevaline du 11 mai 1895 [La France chevaline, May 11, 1895] (in French). Gallica.

- ^ a b Machart, Paul. Le cheval : allures et vitesses [The horse: gaits and speeds] (in French). Paris: Berger-Levrault. p. 43.

- ^ a b Ollivier (1902, p. 14)

- ^ Curot, Edmond (1925). Galopeurs et trotteurs : Hygiène. Elevage. Alimentation. Entraînement. Maladies : 72 figures et graphiques [Gallopers and trotters: Hygiene. Breeding. Feeding. Training. Diseases: 72 figures and charts,] (in French). p. 561.

- ^ d'Hauthuille, Alban (1982). Les Courses de chevaux [Horse racing]. Que sais-je ? (in French). Presses universitaires de France. p. 128.

- ^ Cauchois (1908, p. 62)

- ^ Diffloth, Paul (1904). Zootechnie : Zootechnie général; production et alimentation du bétail. Zootechnie spéciale; cheval, âne, mulet [Zootechnics: General zootechnics; livestock production and feeding. Special zootechnics; horse, donkey, mule]. Encyclopédie agricole (in French). J.-B. Baillière. p. 504.

- ^ Chalopin, P. (1909). Mémoires (in French). Académie nationale des sciences, arts et belles-lettres de Caen. p. 78.

- ^ a b de Choin (1912, p. 70)

- ^ "Nourrit et Cie". La Revue hebdomadaire (in French). 12: 1296. 1906.

- ^ Monte de 1897 – Dépôt d'étalons de Saint-Lô [Riding in 1897 – Saint-Lô stud farm] (in French). La France chevaline.

- ^ Monte de 1905 – Dépôt d'étalons de Saint-Lô [1905 show jumping – Saint-Lô stallion depot] (in French). La France chevaline. 1905.

- ^ a b de Choin (1912, p. 43)

- ^ Gallier (1908, p. 70)

- ^ Guénaux, M. (1900). La plaine de Caen [The Caen plain] (in French). Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale. p. 486.

- ^ Ollivier (1902)

- ^ de Choin (1912, p. 64)

- ^ Gallier (1908, p. 72)

- ^ de Choin (1912, p. 71)

- ^ Dubois, Pierre-Joseph-Louis-Alfred (1912). La crise du demi-sang français : évolution nécessaire [The crisis of the French half-blood: necessary evolution] (in French). Paris. p. 36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ La France chevaline (in French). Gallica. 1911.

- ^ a b Nicard, p. 81)

- ^ Nicard, p. 177)

- ^ a b Quinzaine : revue littéraire, artistique et scientifique [Quinzaine: literary, artistic and scientific review] (in French). Vol. 1. pp. 127–128.

- ^ de Gasté, Maurice. Question du cheval d'arme et le demi-sang galopeur : suivie de La Déformation du modèle par les étalons trotteurs de grande vitesse (in French). Imp. E. Menard et cie. pp. 28–29.

- ^ "Informations générales Narquois" [Narquois general information]. infochevaux.ifce.fr (in French). Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Pedigree 5 générations de Narquois" [5-generation Narquois pedigree]. infochevaux.ifce.fr. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Ollivier (1902, p. 18)

- ^ Nicard, p. 160, 176)

- ^ "Le rôle du Pur-sang anglais dans la production du demi-sang galopeur et du demi-sang trotteur" [The role of the English Thoroughbred in the production of half-bred gallopers and half-bred trotters]. Le Sport universel illustré: 13. 1935.

- ^ Nicard, p. 80)

- ^ Nicard, p. 232)

- ^ Registre des chevaux de demi-sang nés et importés en France, section normande, tome V : étalons (1902–1905) [Register of half-blood horses born and imported into France, Normandy section, Volume V: stallions (1902–1905)] (in French). Gallica. p. 89.

- ^ "Les trotteurs français à l'étranger" [French trotters abroad]. Le Sport universel illustré (in French): 647. 1911.

- ^ de Comminges, Marie-Aimery. Le cheval de selle en France (in French). A. Legoupy. p. 98.

- ^ a b "Société des agriculteurs de France" [French Farmers Society]. Bulletin de la Société des agriculteurs de France (in French): 108. 1910.

- ^ Baume (1913, p. 64)

- ^ Direction de l'agriculture de France (1936). Statistique agricole de la France : Résultats généraux de l'enquête de 1929 [Agricultural statistics for France: General results of the 1929 survey] (in French). Vol. 4. Impr. nationale. p. 803.

- ^ Ollivier (1902)

- ^ Reynaldo (2015, p. 104)

- ^ Reynaldo (2015, p. 109)

- ^ Reynaldo (2015, p. 104, 109)

- ^ Rol, Agence. "Vincennes, passage du prix Narquois, trot monté" [Vincennes, Prix Narquois passage, mounted trotting]. Gallica (in French).

- ^ Résultat Prix Narquois – Paris-Vincennes / R1 – C5 [Result Prix Narquois – Paris-Vincennes / R1 – C5]. Paris-Turf. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

Bibliography[edit]

- Baume, Louis (1913). Influence des courses au trot sur la production chevaline en France [The influence of trotting on horse production in France] (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Cauchois, Louis (1908). Les familles de trotteurs : classification des trotteurs français en familles maternelles numéretées, tables généalogiques et historique des principales familles [Trotter families: classification of French trotters into numbered maternal families, genealogical tables and history of the main families,] (in French). Aux bureau de La France chevaline.

- de Choin, Pierre (1912). Le haras et la circonscription du dépôt d'étalons à Saint-Lô : avec 15 figures et une carte [The Saint-Lô stud farm and stallion depot district: with 15 figures and a map] (in French). Paris: J.-P. Baillière et fils.

- Gallier, Alfred (1900). Le cheval Anglo-Normand : avec photogravures intercalées dans le texte [The Anglo-Norman horse: with photoengravings interspersed in the text] (in French). Paris: Baillière.

- Nicard, Édouard. Le pur sang anglais et le trotteur français devant le transformisme [English thoroughbreds and French trotters in the face of transformism] (in French). Mazeron frères.

- Gallier, Alfred (1908). Le cheval de demi-sang, races françaises [Half-blood horses, French breeds]. L'Agriculture au XXe siècle. Laveur.

- Ollivier, A. (1902). Généalogies chevalines Anglo-Normandes en ligne male [Anglo-Norman horse genealogies online male] (in French). H. Rebuffé.

- Reynaldo, Jean-Pierre (2015). Le trotteur français : Histoire des courses au trot en France des origines à nos jours [Le trotteur français: History of trotting races in France from their origins to the present day] (in French). Éditions Lavauzelle. ISBN 978-2-7025-1638-6.