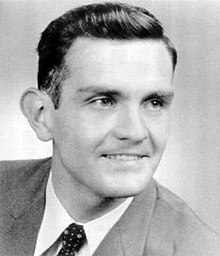

Norman Morrison

Norman Morrison (December 29, 1933 – November 2, 1965) was a Baltimore Quaker best known for his act of self-immolation at age 31 to protest United States involvement in the Vietnam War. The Erie, Pennsylvania-born Morrison graduated from the College of Wooster in 1956. He was married and had two daughters and a son.[1] On November 2, 1965, Morrison doused himself in kerosene and set himself on fire below Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara's Pentagon office.[2] This may have been in emulation of Thích Quảng Đức and other Buddhist monks, who burned themselves to death to protest the repression committed by the South Vietnam government.[3]

Public response

Filmmaker Errol Morris interviewed Secretary McNamara at length on camera in his documentary film, The Fog of War, in which McNamara says, "[Morrison] came to the Pentagon, doused himself with gasoline. Burned himself to death below my office ... his wife issued a very moving statement - 'human beings must stop killing other human beings' - and that's a belief that I shared, I shared it then, I believe it even more strongly today". McNamara then posits, "How much evil must we do in order to do good? We have certain ideals, certain responsibilities. Recognize that at times you will have to engage in evil, but minimize it."

Perhaps the most detailed treatment of Morrison's death appears in The Living and the Dead: Robert McNamara and Five Lives of a Lost War, by prizewinning author Paul Hendrickson, published in 1997.[4]

Morrison took his daughter Emily, then one year of age, to the Pentagon, and either set her down or handed her off to someone in the crowd before setting himself ablaze. Morrison's reasons for taking Emily are not entirely known. However, Morrison's wife later recalled, "Whether he thought of it that way or not, I think having Emily with him was a final and great comfort to Norman... [S]he was a powerful symbol of the children we were killing with our bombs and napalm--who didn't have parents to hold them in their arms."[5]

In a letter he mailed to his wife, Morrison reassured her of the faith in his act. "Know that I love thee ... but I must go to help the children of the priest's village". McNamara described Morrison's death as "a tragedy not only for his family but also for me and the country. It was an outcry against the killing that was destroying the lives of so many Vietnamese and American youth." He was survived by his wife Anne Welsh and three children, Ben (who died of cancer in 1977), Christina and Emily.[6]

Supporters portrayed Morrison as devout and sincere in sacrificing himself for a cause greater than himself. In Vietnam, Morrison quickly became a folk hero to some, his name rendered as Mo Ri Xon.[7] Five days after Morrison died, Vietnamese poet Tố Hữu wrote a poem, "Emily, My Child", assuming the voice of Morrison addressing his daughter Emily and telling her the reasons for his sacrifice.[8]

One week after Morrison, Roger Allen LaPorte performed a similar act in New York City, in front of the United Nations building. On May 9, 1967, as part of the start to the 1967 Pentagon camp-in, demonstrators held a vigil for Morrison, before occupying the Pentagon for four days until being removed and arrested.[3]

Morrison's widow, Anne, and the couple's two daughters visited Vietnam in 1999, where they met with Tố Hữu, the poet who had written the popular poem Emily, My Child.[9] Anne Morrison Welsh recounts the visit and her husband's tragedy in her monograph, Fire of the Heart: Norman Morrison's Legacy In Vietnam And At Home.[10]

On his visit to the United States in 2007, President of Vietnam Nguyễn Minh Triết visited a site on the Potomac near the place where Morrison immolated himself and read the poem by Tố Hữu to commemorate Morrison.[11]

Cultural depictions

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Morrison's widow appears, with her young children, in a segment of the French documentary, Far from Vietnam, in which she calmly describes the circumstances of her husband's death and expresses approval of his act. This footage is interspersed with an interview with a Vietnamese expatriate, Ann Uyen, living in Paris, who describes what Morrison's sacrifice meant to the Vietnamese people.

Morrison's immolation is portrayed in the HBO film Path to War, in which he is portrayed by Victor Slezak.

Morrison is the subject of a poem by Amy Clampitt called "The Dahlia Gardens" in her 1983 book The Kingfisher.

The incident inspired George Starbuck's Of Late.[12]

"Stephen Smith, University of Iowa sophomore, burned what he said was his draft card,"

And Norman Morrison, Quaker, of Baltimore Maryland, burned what he said was himself.

You, Robert McNamara, burned what you said was a concentration of the Enemy Aggressor.

No news medium troubled to put it in quotes."

Legacy

In the Vietnamese city of Đà Nẵng, a road is named after Norman Morrison in memory of his act against the Vietnam-U.S conflict. Parallel to it also is a road named after Francis Henry Loseby. [citation needed]

North Vietnam named a Hanoi street after him, and issued a postage stamp in his honor.[13] Possession of the stamp was prohibited in the United States due to the U.S. embargo against North Vietnam.[14]

See also

- Alice Herz

- Brian Willson

- Florence Beaumont

- George Winne, Jr.

- List of political self-immolations

- Thích Quảng Đức

- Nhat Chi Mai

- Path to War

References

- ^ Profile Archived 2013-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, wooster.edu; accessed December 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Pacifists", Time Magazine, November 12, 1965; accessed July 23, 2007.

- ^ a b Tucker, Spencer C. (2011). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, The: A Political, Social, and Military History (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 775. ISBN 978-1-85109-960-3. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ The Washington Post. Washington, D.C., November 4, 1999, p. C14.

- ^ Hollyday, Joyce (July–August 1995). Grace Like a Balm, Sojourners Magazine

- ^ Steinbach, Alice (July 30, 1995). "Quaker Sets Himself On Fire". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ My Lai Peace Park website Archived 2004-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Christian G. Appy (2008) Vietnam: the Definitive Oral History Told From All Sides. Ebury Press, p. 155

- ^ Steinbach, Alice (July 30, 1995). Norman Morrison: Thirty years ago a Baltimore Quaker set himself on fire to protest the war in Vietnam. Did it make a difference?, The Baltimore Sun

- ^ John-Paul Flintoff, I told them to be brave, The Guardian, October 16, 2010.

- ^ Thanh Tuấn (July 7, 2007). "Đọc thơ Tố Hữu bên bờ sông Potomac". Tuoi Tre. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ ""of Late"". Poetryfoundation.org. Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ BBC (21 december, 2010). A life in flames: Anne Morrison Welch

- ^ Mitchell, Greg (13 November 2010). "When Antiwar Protest Turned Fatal: The Ballad of Norman Morrison". The Nation. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

Further reading

- Welsh, Anne Morrison & Joyce Hollyday. Held in the light: One Man's Sacrifice for Peace and His Family's Search for Healing, Orbis (2008); ISBN 978-1-57075-802-7

- King, Sallie B. (2000). They Who Burned Themselves for Peace: Quaker and Buddhist Self-Immolators during the Vietnam War, Buddhist-Christian Studies 20, 127-150

- Patler, Nicholas. Norman's Triumph: The Transcendent Language of Self-Immolation, Quaker History, Fall 2015, 18-39.

External links

- Claus Bernet (2009). "Norman Morrison". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 30. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 1023–1024. ISBN 978-3-88309-478-6.