Original six frigates of the United States Navy

USS Constitution, the last of the original six frigates of the United States Navy still commissioned.

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | United States Navy |

| Preceded by | None |

| Built | 1794 - 1800 |

| In commission | 1797 - present |

| Planned | 6 |

| Completed | 6 |

| Active | 1 |

| Lost | 2 |

| Retired | 3 |

| General characteristics (Constitution; President; United States) | |

| Class and type | 44-gun frigate[1] |

| Tonnage | 1,576[2] |

| Displacement | 2,200 tons[2] |

| Length | list error: <br /> list (help) 204 ft (62 m) (length overall); 175 ft (53 m) at waterline[1] |

| Beam | 43 ft 6 in (13.26 m)[1] |

| Draft | list error: <br /> list (help) 21 ft (6.4 m) forward 23 ft (7.0 m) aft[2] |

| Depth of hold | 14 ft 3 in (4.34 m)[3] |

| Complement | 450 officers and enlisted, including 55 Marines and 30 boys[1] |

| General characteristics (Congress and Constellation) | |

| Class and type | 38-gun Frigate[4] |

| Tonnage | 1,265 tons[4] |

| Length | 164 ft (50 m) between perpendiculars[4] |

| Beam | 41 ft (12 m)[4] |

| Complement | 340 officers and enlisted[4] |

| General characteristics (Chesapeake) | |

| Class and type | 38-gun Frigate[5] |

| Tonnage | 1,244[5] |

| Length | 152.8 ft (46.6 m) between perpendiculars[5] |

| Beam | 41.3 ft (12.6 m)[5] |

| Draft | 20 ft (6.1 m)[5] |

| Depth of hold | 13.9 ft (4.2 m)[6] |

| Complement | 340 officers and enlisted[5] |

The United States Congress authorized the original six frigates of the United States Navy with the Naval Act of 1794 on 27 March 1794 at a total cost of $688,888.82. These ships were built during the formative years of the United States Navy, on the recommendation of designer Joshua Humphreys for a fleet of frigates powerful enough to engage any frigates of the French or British navies yet fast enough to evade any ship of the line.

Purpose

After the Revolutionary War, a heavily indebted United States disbanded the Continental Navy, and in August 1785, lacking funds for ship repairs, sold its last remaining warship, the Alliance.[7][8] But almost simultaneously troubles began in the Mediterranean when Algiers seized two American merchant ships and held their crews for ransom.[9][10] Minister to France Thomas Jefferson suggested an American naval force to protect American shipping in the Mediterranean, but his recommendations were initially met with indifference, as were the recommendations of John Jay, who proposed building five 40-gun warships.[9][11] Shortly afterward, Portugal began blockading Algerian ships from entering the Atlantic Ocean, thus providing temporary protection for American merchant ships.[12][13]

Piracy against American merchant shipping had not been a problem when under the protection of the British Empire prior to the Revolution, but after the Revolutionary War the "Barbary States" of Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis felt they could harass American merchant ships without penalty.[14][15] Additionally, once the French Revolution started, Britain began interdicting American merchant ships suspected of trading with France and France began interdicting American merchant ships suspected of trading with Britain. Defenseless, the American government could do little to resist.[16][17]

The formation of a naval force had been a topic of debate in the new America for years. Opponents argued that building a navy would only lead to calls for a navy department, and the staff to operate it. This would further lead to more appropriations of funds, which would eventually spiral out of control, giving birth to a "self-feeding entity". Those opposed to a navy felt that payment of tribute to the Barbary States and economic sanctions against Britain were a better alternative.[18][19]

In 1793 Portugal reached a peace agreement with Algeria, ending its blockade of the Mediterranean, thus allowing Algerian ships back into the Atlantic Ocean. By late in the year eleven American merchant ships had been captured.[12] This, combined with the actions of Britain, finally led President Washington to request Congress to authorize a navy.[20][21]

On 2 January 1794, by a narrow margin of 46-44, the House of Representatives voted to authorize building a navy and formed a committee to determine the size, cost, and type of ships to be built. Secretary of War Henry Knox submitted proposals to the committee outlining the design and cost of warships.[22][23] To appease the strong opposition to the upcoming bill, the Federalist Party inserted a clause into the bill that would bring an abrupt halt to the construction of the ships should the United States reach a peace agreement with Algiers.[24][25]

The bill was presented to the House on 10 March and passed as the Naval Act of 1794 by a margin of 50-39, and without division in the Senate on the 19th.[24][25] President Washington signed the Act on 27 March. It provided for acquisition, by purchase or otherwise, of four ships to carry forty-four guns each, and two ships to carry thirty-six guns each.[26] It also provided pay and sustenance for naval officers and sailors, and outlined how each ship should be manned in order to operate them. The Act appropriated $688,888.82 to finance the work.[27][28]

Design and preparations

With the formation of a Department of the Navy still several years away, responsibility for design and construction fell to the Department of War, headed by Secretary Henry Knox. As early as 1790 Knox had consulted various authorities regarding ship design.[29] Discussions of the designs were carried out in person at meetings in Philadelphia. Little is known about these discussions due to a lack of written correspondence, making determination of the actual designers involved difficult to assemble.[30] Secretary Knox reached out to ship architects and builders in Philadelphia, which was the largest seaport in North America at the time and possibly the largest freshwater port in the world. This meant that many discussions of ship design took place in Knox's office, resulting in few if any records of these discussions being available to historians. Joshua Humphreys is generally credited as the designer of the six frigates, but Revolutionary War ship captains John Foster Williams and John Barry and shipbuilders Josiah Fox and James Hackett also were consulted.[31][32]

The final design plans submitted to President Washington for approval called for building new frigates rather than purchasing merchant ships and converting them into warships, an option under the Naval Act.[29] The design was unusual for the time, being long on keel and narrow of beam (width); mounting very heavy guns; incorporating a diagonal scantling (rib) scheme aimed at limiting hogging; while giving the ships extremely heavy planking. This gave the hull greater strength than the hulls of other navies' frigates. The designers realized that the fledgling United States could not match the European states in the number of ships afloat. Therefore the new frigates had the ability to overpower other frigates, but were capable of a speed to escape from a ship of the line.[33][34][35] Knox advised President Washington that the cost of new construction would likely exceed the appropriations of the Naval Act. Despite this, Washington accepted and approved the plans the same day they were submitted, 15 April 1794.[31]

Joshua Humphreys was appointed Master Constructor of the ships. An experienced draftsman, Josiah Fox, was hired into the War Department to put plans to paper. However, Fox disagreed with the large dimensions of the design and, according to Humphreys, attempted to downsize the measurements while producing his drafts. This incensed Humphreys enough that Fox was soon assigned to the mold loft with William Doughty.[36]

After or simultaneously with the creation of the drawings, a builder's half model was assembled from which measurements were taken to create molds of the timbers. In a process known as "molding", the dimensions of the framing pieces were chalked onto the floor of a mold loft where a template was formed using strips of light wood.[37] Once the molds were transported to the timber crews, the templates were used to select the part of a tree that closely matched the template. From there the timber was felled and roughed out close to the required dimensions, then numbered for identification and loaded onto a ship for transport.[citation needed] An additional set of more detailed molds was required for each frigate for the construction crews to follow.

Construction

Secretary Knox suggested to President Washington that six different construction sites be used, one for each ship, rather than building at one particular shipyard. Separate locations enabled the alloted funds to stimulate each local economy, and Washington approved the sites on 15 April 1794. At each site, a civilian naval constructor was hired to direct the work. Navy captains were appointed as superintendents, one for each of the six frigates as follows:[31][38]

| Ship | Site | Guns[Note 1] | Naval constructor | Superintendent | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chesapeake | Gosport, Virginia | 44 | Josiah Fox | Richard Dale | [40] |

| Constitution | Boston, Massachusetts | 44 | George Claghorn | Samuel Nicholson | [40] |

| President | New York, New York | 44 | Christian Bergh | Silas Talbot | [41] |

| United States | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 44 | Joshua Humphreys | John Barry | [40] |

| Congress | Portsmouth, New Hampshire | 36 | James Hackett | James Sever | [40] |

| Constellation | Baltimore, Maryland | 36 | David Stodder | Thomas Truxtun | [40] |

Humphreys wished to use the most durable materials available for construction, primarily white pine, longleaf pine, white oak, and, most importantly, southern live oak.[42] Live oak was used for framing as it was a strong, dense, and long-lasting wood weighing up to 75 lb per cubic foot (1,200 kg/m3) when freshly cut.[43] The live oak tree grows primarily in coastal areas of the United States from Virginia to Texas, with the most suitable timber found in the coastal areas of Georgia near St. Simons.[42][44] This desire for live oak was the primary cause of delays in the frigates' construction. Appropriated funds from the Naval Act were not available until June 1794.[45] Shipbuilder John T. Morgan was hired by the War Department to procure the live oak and supervise the cutting and crews. Morgan wrote to Humphreys in August reporting that it had hardly ceased raining since his arrival and "the whole country is almost under water". Captain John Barry was sent to check up on progress in early October; he found Morgan and several persons sick with malaria. Timber cutting finally began when the crews arrived on the 22nd.[46] The earliest delivery of timber occurred in Philadelphia on 18 December, but another load of live oak destined for New York was lost when its cargo ship sank. Delays continued to plague the timber cutting and delivery operations throughout 1795. By December of that year all six keels had been laid down, though the frigates were still unframed and far from finished.[47][48]

Construction of the frigates slowly continued until the 1796 announcement of the Treaty of Tripoli, which was witnessed by Algiers. In accordance with the clause in the Naval Act, construction of the frigates was to be discontinued. However, President Washington instead requested instructions from Congress on how to proceed. Several proposals circulated before a final decision was reached allowing Washington to complete two of the 44-gun and one of the 36-gun frigates.[49] The three frigates nearest to completion, United States, Constellation and Constitution, were chosen.[50] Construction of Chesapeake, Congress, and President was halted, and some of their construction materials were sold or placed in storage.[51] The captains and naval constructors were laid off.[citation needed]

The earlier predictions of Henry Knox regarding costs of the frigates came to a head in early 1797. Of the original appropriation of $688,888.82, only about $24,000 remained. Secretary of War James McHenry requested of Congress an additional $200,000, but only $172,000 was appropriated. The additional funds were enough to finish the three frigates' construction, but did not allow them to be manned and put to sea.[52] United States launched on 10 May,[53] Constellation on 7 September,[4] and Constitution on 21 October.[3] Meanwhile, interference with American shipping by France because of their disagreement over the Jay Treaty prompted Congress to debate authorizing completion and manning of the three frigates. Secretary McHenry reported that an additional $200,000 would be required for this stage of construction, touching off grumbling in Congress over the escalating costs. Nevertheless, on 1 July Congress approved the completion and appropriated the requested funds.[54]

When the next session of Congress convened in November, Secretary McHenry again requested funds to complete the three frigates. Though upset over the escalating costs, Congress approved an additional $115,833, but simultaneously launched an investigation into possible waste or fraud in the frigate program. On 22 March 1798, McHenry turned over a report outlining several main reasons for cost escalations: problems procuring the live oak; the logistics of supplying six separate shipyards; and fires, yellow fever, and bad weather.[55] Additional inquiries prior to McHenry's report revealed that the War Department used substandard bookkeeping practices, and that the authorized funds had to be released by the Treasury Department, resulting in delays, causing waste. These problems led to the formation of the Department of the Navy on 30 April.[56] In the case of the "President", construction was begun at New York in the shipyard of Foreman Cheesman and work on her was discontinued in 1796. Construction resumed in 1798, under Christian Bergh and naval constructor William Doughty.[41]

Simultaneously, relations with France soured even further when President John Adams informed Congress of the XYZ Affair. In response, on 28 May, Congress authorized vessels of the United States to capture any armed French vessels lying off the coast of the United States. As Constellation, Constitution, and United States were still fitting out, the first U.S. Navy vessel to put to sea for this undeclared Quasi-War was the sloop Ganges with Richard Dale in command.[57][58] Finally, on 16 July Congress appropriated $600,000 for completion of the remaining three frigates; Congress launched on 15 August 1799,[59] Chesapeake on 2 December,[5] and President on 10 April 1800.[60][61][62]

Armament

The 44-gun ships usually carried 50 or more guns, and "Constitution" was known[1] to carry 24-pounder guns in her main battery instead of the normal 18-pounders most frigates carried.[citation needed]

The Naval Act of 1794 had specified 36-gun frigates in addition to the 44s, but at some point the 36s were re-rated as 38s.[63] Their "ratings" by number of guns was meant only as an approximation.[64]

Ships of this era usually had no permanent battery of guns, such as modern Navy ships carry. The guns and cannons were designed to be completely portable, and often were exchanged between ships or shore as situations warranted. Each commanding officer generally outfitted armaments to his liking, taking into consideration factors such as the overall tonnage of cargo, complement of personnel on board, and planned routes to be sailed. Consequently, the armaments on ships would change many times during their careers, and records of the changes were not generally kept.[65]

Commonly, twelve men and a powder-boy were required to operate each gun.[66] If needed, some men were designated to take stations as boarders, to man the bilge pumps, or to fight fires. Guns were normally manned on the engaged side only; if a ship engaged two opponents, gun crews had to be divided. All of the guns were capable of using several different kinds of projectiles: Round shot, chain or bar shot, grape shot, and heated shot.[67] Each gun was mounted on a wooden gun carriage controlled by an arrangement of rope and tackle. The Captain ordered the gun crews to either open fire together in a single broadside, or allowed each crew to fire at will as the target came close alongside. The gun captain pulled the lanyard to trip the flintlock which sent a spark into the pan. The ignited powder in the pan sent a flame through the priming tube to set off the powder charge in the gun and hurl its projectile at the enemy.

The marine detachment on board provided the naval infantry that manned the fighting tops, armed with muskets to fire down onto the decks of the enemy ship.[66]

The frigates

The frigates were originally designated by the letters A through F until March 1795, when Secretary of War, Timothy Pickering, prepared a list of ten suggested names for the ships. President Washington was responsible for selecting five of the names: Constitution, United States, President, Constellation, and Congress, each of which represented a principle of the United States Constitution. The sixth frigate, Chesapeake, remained nameless until 1799, when Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddert, designated her a namesake of the Chesapeake Bay, ignoring the previous Constitutional naming protocol.[5][68][69]

United States

United States was built in Philadelphia, launched on 10 May 1797, and commissioned on 11 July 1797. On 25 October 1812, United States fought and captured the frigate HMS Macedonian. United States was decommissioned on 24 February 1849 and placed in ordinary at Norfolk, Virginia. In 1861, while still in ordinary at Norfolk, the ship was seized and commissioned into the Confederate States Navy, which later scuttled the ship. In 1862, Union forces raised the scuttled ship and retained control until she was broken up in 1865.

Constellation

Constellation was built in Baltimore and launched on 7 September 1797. On 9 February 1799, she fought and captured the French frigate Insurgente. This was the first major victory by an American-designed and -built warship. In February 1800, Constellation fought the French frigate Vengeance. Although Vengeance was not captured or sunk, she was so badly damaged that her captain intentionally grounded the ship to prevent her from sinking. Constellation was struck in 1853 and broken up. Some timbers were re-used in the building of a new Constellation, and it was claimed that it was a "repair" of the original ship (a common dodge of the time for political reasons) leading to uncertainty over which ship was preserved in Baltimore until it was proven in 1999 to be the second Constellation.[70]

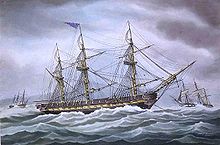

Constitution

Constitution, rated at 44 guns, launched from Edmund Hartt's shipyard in Boston, Massachusetts on 21 October 1797 by naval constructor George Claghorn and Captain Samuel Nicholson.[42] During the Quasi-War she captured the French merchant ship Niger,[71] and was later involved in the defeat of the Barbary pirates in the First Barbary War.

She is most well known for her actions during the War of 1812 against Britain, when she captured numerous merchant ships and defeated four British warships: HMS Guerriere, HMS Java, HMS Cyane, and HMS Levant. The battle with the Guerriere earned her the nickname of "Old Ironsides" and public adoration that has repeatedly saved her from scrapping. She continued to actively serve the nation as flagship in the Mediterranean and African squadrons and made a circumnavigation of the world in the 1840s. During the American Civil War she served as a training ship for the United States Naval Academy and carried artwork and industrial displays to the Paris Exposition of 1878. Retired from active service in 1881, she served as a receiving ship until designated a museum ship in 1907. In 1931 she made a three-year, 90-port tour of the nation, and in 1997 she finally sailed again under her own power for her 200th birthday.

Constitution is berthed at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Massachusetts and is used to promote understanding of the Navy’s role in war and peace through educational outreach, historic demonstration, and active participation in public events. Constitution is open to visitors year-round, providing free tours, with the USS Constitution Museum nearby. She is the oldest commissioned vessel afloat in the world.[Note 2]

Chesapeake

Chesapeake was built at the Gosport Navy Yard, Virginia, and was launched on 2 December 1799. The Chesapeake was the only one of the six frigates to be disowned by Humphreys due to liberties taken by her Master Constructor Josiah Fox during construction relating to overall dimensions.[citation needed] The frigate that became Chesapeake was originally planned as a 44-gun ship, but when her construction began in 1798 Josiah Fox altered the original design plan, resulting in the ship's re-rating to 36 guns.[73] Fox's reason for making the alteration is not clear, but may be attributed to construction materials that were diverted to complete Constellation. Additionally, Fox and Humphreys had earlier disagreed over the design of the six frigates, and Fox may have taken opportunities during construction to make alterations to his own liking. Regardless, the plan for the redesigned frigate was approved by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert.[68]

When construction finished on Chesapeake, she had the smallest dimensions of all six frigates.[74] A length of 152.8 ft (46.6 m) between perpendiculars and 41.3 ft (12.6 m) of beam contrasted with the other two 36-gun frigates, Congress and Constellation, which were built to 164 ft (50 m) in length and 41 ft (12 m) of beam.[4][59][75]

On 22 June 1807, what has become known as the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair occurred when the Chesapeake was fired upon by HMS Leopard for refusing to comply with a demand to permit a search for deserters from the Royal Navy. After several quick broadsides from Leopard, to which the Chesapeake replied with only one gun, the Chesapeake struck her colors. HMS Leopard refused the surrender, searched the Chesapeake, captured four alleged deserters, and sailed to Halifax. Chesapeake was captured on 1 June 1813 by HMS Shannon shortly after sailing from Boston, Massachusetts. Taken into Royal Navy service, she was later sold, and broken up at Portsmouth, England, in 1820.

Congress

Congress—rated at 38 guns—was launched on 15 August 1799 under the command of Captain James Sever. Beginning her maiden voyage on 6 January 1800, she headed for the East Indies,[76] but soon after her masts were destroyed in a gale, forcing her return to port; repairs took six months. She sailed again on 26 July for the West Indies and made uneventful patrols through April 1801.[77][78]

Under the command of John Rodgers, Congress sailed for the Mediterranean in June 1804 and performed services during the First Barbary War. She assumed blockade duties off Tripoli and participated in the capture of a xebec in October. In July 1805, she helped to blockade Tunisia, and in September of that year carried the Tunisian ambassador back to Washington, D.C. Afterward, she served as a classroom for midshipman training through 1807.[79][80][81]

Under the command of Captain John Smith during the War of 1812, she made three extended cruises in company with President and briefly with United States. She was part of a pursuit of a fleet of British merchant ships and assisted President in the attempted capture of HMS Belvidera. On the return voyage, Congress and President captured seven merchant ships. Congress' second cruise began in October 1812, and she pursued HMS Galatea and captured the merchant ship Argo. Arriving back in Boston on 31 December, she assisted in capturing eight additional merchant ships. After repairs, she sailed in company with President on 30 April 1813 and pursued HMS Curlew, which escaped. Setting off on her own, she made a lengthy voyage off the Cape Verde Islands and the coast of Brazil. During this long cruise she captured only four small merchant ships, returning home in late 1813. Because of a lack of materials to repair her, she was placed in ordinary for the remainder of the war.[82][83][84]

In 1815 she returned to active service for the Second Barbary War under Captain Charles Morris, and in August Congress joined a squadron and began patrol duties, subsequently making appearances off Tripoli and Tunis. Returning to Boston, she decommissioned in December.[85] She patrolled against piracy in the Gulf of Mexico from December 1816 to July 1817 and made a voyage to South America in 1818. Early in 1819 she made a voyage to China, becoming the first U.S. warship to visit that country.[86] In 1822 she served as the flagship of James Biddle, combating piracy in the West Indies. Under Biddle she made a voyage to Spain and Argentina. She began serving as a receiving ship in 1824 and remained on that duty until ordered broken up in 1834.[87][88][89]

President

Minor alterations were made to President based on experience gained in constructing the 44-gun ships Constitution and United States. Humphreys instructed President's naval contractor to raise the gun deck by 2 in (5.1 cm) and move the mainmast 2 ft (61 cm) farther aft.[90]

Rated at 44 guns, President was the last frigate to be completed, launching from New York City on 10 April 1800 with Captain Thomas Truxtun in command. She departed for patrols during the Quasi-War on 5 August and recaptured several American merchant ships. After the peace treaty, she returned to the United States in March 1801.[91]

In May 1801 she sailed under the command of Richard Dale for service in the First Barbary War. She made appearances off Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, capturing a Greek vessel with Tripolitan soldiers aboard and participating in a prisoner exchange. She returned to the United States on 14 April 1802,[92][93][94] then left for a second patrol on the Barbary coast in 1804 under the command of Samuel Barron. In company with Congress, Constellation, and Constitution, President experienced a mostly uneventful tour, assisting in the capture of three vessels, performing blockade duties, and undergoing two changes of commanding officers. She sailed for home on 13 July 1805, carrying with her many sailors released from captivity in Tripoli.[95][96]

On 16 May 1811, in what became known as the Little Belt Affair, President, under the command of Captain John Rodgers, mistakenly identified HMS Little Belt as the frigate HMS Guerriere while searching for impressed American sailors taken by the Royal Navy. Though the sequence of events is disputed on both sides, both ships discharged cannon for several minutes before Rodgers determined that Little Belt was a much smaller ship than Guerriere. Little Belt suffered serious damage and thirty-one killed or wounded in the exchange. Rodgers offered assistance to Little Belt's Captain Arthur Bingham, but he declined and sailed off for Halifax, Nova Scotia. The U.S. and Royal Navy investigations each determined the other ship to be responsible for the attack, increasing tensions leading up to the War of 1812.[97][98][99]

Still under the command of John Rodgers, President made three extended cruises during the War of 1812 in company with Congress and briefly with United States. President encountered HMS Belvidera and engaged in a fight from which Belvidera eventually escaped.[100][101] Pursuing a fleet of merchant ships, President sailed to within a day's journey of the English Channel before returning to Boston, capturing seven merchant ships en route.[102][103] Her second cruise began with a pursuit of HMS Nymphe and HMS Galatea, but she failed to overtake either of them. Later prizes were the packet ship Swallow, carrying a large amount of currency, and eight other merchant ships. President returned on 31 December.[104][105] Her third cruise of the war began 30 April 1813 with her pursuit of HMS Curlew, but she once again lost a race to overtake an enemy ship. President spent five months at sea, capturing several merchant ships, but the only highlight was the capture of HMS Highflyer in late September.[106][107]

After the ship spent a year blockaded in port, Stephen Decatur assumed command of President. On the evening of 14 January 1815, President headed out of New York harbor but ran aground, suffering severe damage to her keel and masts. Unable to return to port, she was forced to head out to sea. Later the next afternoon she fought a battle with HMS Endymion. Decatur attempted to capture Endymion to replace President, but this plan failed because of President's damaged condition. Subsequently HMS Pomone and HMS Tenedos overtook President, and Decatur surrendered the ship.[108] [109] President was taken into the Royal Navy as HMS President, but served only a few years before being broken up in 1818.[110]

Notes

- ^ Chesapeake's altered construction led to her rerating as a 36 gun ship. Because of their larger dimensions over Chesapeake, Congress and Constellation were rerated to 38s.[39]

- ^ HMS Victory is the oldest commissioned vessel by three decades; however, Victory has been in dry dock since 1922.[72]

References

- ^ a b c d e "US Navy Fact File - Constitution". United States Navy. 7 July 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ a b c Hollis (1900), p. 39.

- ^ a b "Constitution". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Constellation". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Chesapeake". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ Chapelle (1949), p. 535.

- ^ Daughan (2008), p. 240.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 8.

- ^ a b Daughan (2008), p. 242.

- ^ Fowler (1984), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Fowler (1984), pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Allen (1905), p. 15.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 9.

- ^ Smelser (1959), p. 8.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 13.

- ^ Daughan (2008), pp. 276–277.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 48–51.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 5–20.

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 42.

- ^ Daughan (2008), pp. 278–279.

- ^ Fowler (1984), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Daughan (2008), p. 279.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 18.

- ^ a b Daughan (2008), pp. 279–281.

- ^ a b Smelser (1959), p. 57.

- ^ Daughan (2008), p. 281.

- ^ An Act to provide a Naval Armament. 1 Stat. 350 (1794). Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 49.

- ^ a b Fowler (1984), p. 20.

- ^ Toll, Ian W. (2006). Six Frigates. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. p. 45.

- ^ a b c Smelser (1959), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 21.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 49–53.

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 29–30, 33.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 42–45.

- ^ Humphreys (1916), p. 401.

- ^ Wood (1981), pp. 88–90.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 24.

- ^ Beach (1986), p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e "Navy History: Federal/Quasi War". Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ a b Canney, Donald (2001), Sailing Warships of the US Navy p. 38.

- ^ a b c Hollis (1900), p. 48.

- ^ Wood (1981), p. 4.

- ^ Wood (1981), p. 3.

- ^ Smelser (1959), p. 74.

- ^ Wood (1981), pp. 25–28.

- ^ Wood (1981), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 76–77.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Daughan (2008), p. 294.

- ^ Smelser (1959), p. 77.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 90–91, 99.

- ^ "United States". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 102, 110, 116–118.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 127, 131–132.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 150–156.

- ^ Smelser (1959), pp. 160–166.

- ^ "Ganges". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Congress". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ "President". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ Daughan (2008), p. 315.

- ^ Smelser (1959), p. 193.

- ^ Chapelle (1949), p. 128.

- ^ Roosevelt 1882, Chapter V

- ^ Jennings 1966, pp. 17–19

- ^ a b Reilly, Jr., John C (4 February 2008). "The Constitution Gun Deck". Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Jennings 1966, p. 224

- ^ a b Beach (1986), p. 31.

- ^ Toll {2006}, p. 61.

- ^ http://www.dt.navy.mil/cnsm/docs/fouled_anchors.pdf

- ^ Jennings (1966), p. 44.

- ^ "HMS Victory Service Life". HMS Victory website. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 56.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 289.

- ^ Fowler (1984), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 136.

- ^ Morris (1880), pp. 120–122.

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 221.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 224–227, 252, 282.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 199, 219–220, 268–269.

- ^ Cooper (1856), pp. 221–222.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 72–74, 76–78, 106–107, 174–175.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 322, 325, 521.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 419–420.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 292–294.

- ^ Raymond, William (1851). Biographical Sketches of the Distinguished Men of Columbia County. Albany: Weed, Parsons. p. 47. OCLC 3720201.

- ^ Morris (1880), pp. 181–184, 190–191.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 2, pp. 20, 28.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 474.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 107.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 217, 221.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 92, 94–95, 98–100.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 228, 231–233.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 153.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 198–199, 218–223, 270.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 224–227, 250–251.

- ^ Cooper (1856), pp. 235–238.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 321–323.

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 69–70.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 73–76.

- ^ Cooper (1856), pp. 244–247.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 77.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 426–427.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 174–177.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 521–522.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 401–404.

- ^ Cooper (1856), pp. 429–432.

- ^ Winfield (2008), p. 124.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

Bibliography

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1905). Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs. Boston, New York and Chicago: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 2618279.

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1909). Our Naval War With France. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1202325.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Beach, Edward L. (1986). The United States Navy 200 Years. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 978-0-03-044711-2. OCLC 12104038.

- Canney, Donald L. (2001). Sailing warships of the US Navy. Naval Institute Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-55750-990-1.

- Chapelle, Howard Irving (1949). The History of the American Sailing Navy; the Ships and Their Development. New York: Norton. OCLC 1471717.

- Cooper, James Fenimore (1856). History of the Navy of the United States of America. New York: Stringer & Townsend. OCLC 197401914.

- Daughan, George C. (2008). If By Sea: The Forging of *the American Navy-- From the American Revolution to the War of 1812. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01607-5. OCLC 190876973.

- Fowler, William M. (1984). Jack Tars and Commodores: The American Navy, 1783-1815. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-35314-9. OCLC 10277756.

- Hollis, Ira N. (1900). The Frigate Constitution; The Central Figure of the Navy Under Sail. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 2350400.

- Humphreys, Henry H. (1916). "Who Built the First United States Navy?". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. XL (4). Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania: 385–411. ISSN 0031-4587. OCLC 1762062.

- Jennings, John (1966). Tattered Ensign The Story of America's Most Famous Fighting Frigate, U.S.S. Constitution. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. OCLC 1291484.

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton; Smith, Roy Campbell (1898) [1893]. A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898. Vol. 1 (New ed.). New York: D. Appleton. OCLC 609036.

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton (1898) [1893]. A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898. Vol. 2 (New ed.). New York: D. Appleton. OCLC 609036.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Martin, Tyrone G. (2003) [1997]. A Most Fortunate Ship: A Narrative History of "Old Ironsides" (Revised ed.). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-513-9. OCLC 51022876.

- Morris, Charles (1880). Soley, J. R. (ed.). "The Autobiography of Commodore Charles Morris U.S.N." Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. VI (12). Annapolis: United States Naval Institute: pp. 111–219. ISSN 0041-798X. OCLC 2496995.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Roosevelt, Theodore (1883) [1882]. The Naval War of 1812 (3rd ed.). New York: G.P. Putnam's sons. OCLC 133902576.

- Smelser, Marshall (1959). The Congress Founds the Navy, 1787–1798. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. OCLC 422274.

- Toll, Ian W (2006). Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the US Navy. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05847-5. OCLC 70291925.

- Wood, Virginia Steele (1981). Live Oaking: Southern Timber for Tall Ships. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 0-930350-31-6. OCLC 7795440.

Further reading

- Hoyt, Edwin Palmer (2000). Old Ironsides (Large Print). Thorndike: G.K. Hall. ISBN 0-7838-9151-2. OCLC 44468774.

- Humphreys, Assheton Y. (2000). Tyrone G. Martin (ed.). The USS Constitution's Finest Fight: The Journal of Acting Chaplain Assheton Humphreys, US Navy. Mount Pleasant: Nautical & Aviation Publishing. ISBN 1-877853-60-7. OCLC 44632941.

- Poolman, Kenneth (1962). Guns Off Cape Ann; The Story of the Shannon and the Chesapeake. Chicago: Rand McNally. OCLC 1384754.

- Wachtel, Roger (2003). Old Ironsides (Elementary and Junior High School). New York: Children's Press. ISBN 0-516-24207-5. OCLC 50035427.

External links