Orthodoxy

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (February 2016) |

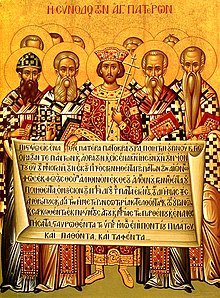

Orthodoxy (from Greek ὀρθοδοξία, orthodoxia – "right opinion")[1] is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.[2] In the Christian sense the term means "conforming to the Christian faith as represented in the creeds of the early Church".[3] The first seven Ecumenical Councils were held between the years of 325 and 787 with the aim of formalizing accepted doctrines.

In some English speaking countries, Jews who adhere to all the traditions and commandments of the Torah are often called Orthodox Jews, though the term "orthodox" historically first described Christian beliefs.

Religious Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy in Christianity

In classical Christian usage, the term orthodox refers to the set of doctrines which were believed by the early Christians. A series of ecumenical councils, also known as the First seven Ecumenical Councils, were held over a period of several centuries to try to formalize these doctrines. The most significant of these early decisions was that between the Homoousian doctrine of Athanasius and Eustathius (which became Trinitarianism) and the Heteroousian doctrine of Arius and Eusebius (called Arianism). The Homoousian doctrine, which defined Jesus as both God and man with the hypostatic union of the 451 Council of Chalcedon, won out in the Church and was referred to as orthodoxy in most Christian contexts, since this was the viewpoint of the majority. (The minority nontrinitarian Christians object to this terminology).

The earliest (first) recorded use of the term "orthodox" is in the Codex Iustinianus of 529-534,[4] but "heterodoxy" was in use from the beginning of the first century of Christianity.[5]

Following the 1054 Great Schism, both the Western and Eastern Churches continued to consider themselves uniquely orthodox and catholic. Over time, the Western Church gradually identified with the "Catholic" label, and people of Western Europe gradually associated the "Orthodox" label with the Eastern Church (in some languages the "Catholic" label is not necessarily identified with the Western Church). This was in note of the fact that both Catholic and Orthodox were in use as ecclesiastical adjectives as early as the 2nd and 4th centuries respectively. Today the two largest "Orthodox" Christian communions are the Eastern Orthodox Church (often simply "Orthodoxy") and Oriental Orthodoxy.

Orthodoxy in Judaism

Orthodox Judaism is the approach to religious Judaism which subscribes to a tradition of mass revelation and adheres to the interpretation and application of the laws and ethics of the Torah as legislated in the Talmudic texts by the Tannaim and Amoraim. Orthodox Judaism is split into various different movements and factions. They have different ways of interpreting and following the laws and traditions of Judaism, and include movements such as Modern Orthodox Judaism (אורתודוקסיה מודרנית) and Ultra-Orthodox or Haredi Judaism (יהדות חרדית). Orthodox Judaism is distinct from Conservative Judaism.

Orthodoxy in Islam

The term Orthodox Islam generally refers to the doctrinal teachings and religious practices of traditional Sunni Islam, which is a main branch of Islam.

Orthodoxy in Hinduism

The term Orthodox Hinduism commonly refers to the religious teachings and practices of Sanātanī, one of the traditionalist branches of Hinduism.

Non-religious contexts

Outside the context of religion, the term "orthodoxy" is often used to refer to any commonly held belief or set of beliefs in some field, in particular when these tenets, possibly referred to as "dogmas", are being challenged. In this sense, the term has a mildly pejorative connotation.

Among various "orthodoxies" in distinctive fields, most common terms are:

- Political orthodoxy,

- Social orthodoxy,

- Economic orthodoxy,

- Scientific orthodoxy,

- Artistic orthodoxy.

Related concepts

Orthodoxy is opposed to heterodoxy ("other teaching") or heresy. People who deviate from orthodoxy by professing a doctrine considered to be false are called heretics, while those who, perhaps without professing heretical beliefs, break from the perceived main body of believers are called schismatics. The term employed sometimes depends on the aspect most in view: if one is addressing corporate unity, the emphasis may be on schism; if one is addressing doctrinal coherence, the emphasis may be on heresy. A deviation lighter than heresy is commonly called error, in the sense of not being grave enough to cause total estrangement, while yet seriously affecting communion. Sometimes error is also used to cover both full heresies and minor errors.

The concept of orthodoxy is prevalent in many forms of organized monotheism. However, orthodox belief is not usually overly emphasized in polytheistic or animist religions, in which there is often little or no concept of dogma, and varied interpretations of doctrine and theology are tolerated and sometimes even encouraged within certain contexts. Syncretism, for example, plays a much wider role in non-monotheistic (and particularly, non-scriptural) religion. The prevailing governing norm within polytheism is often orthopraxy ("right practice") rather than the "right belief" of orthodoxy.

See also

Bibliography

- John B. Henderson: The Construction of Orthodoxy and Heresy: Neo-Confucian, Islamic, Jewish, and Early Christian Patterns, SUNY Press 1998.

References

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "orthodoxy". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ^ orthodox. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Dictionary definition (accessed: March 03, 2008).

- ^ Robert M. Wills (2013). Taking Caesar Out of Jesus: Uncovering the Lost Relevance of Jesus. Xlibris Corporation. p. 246. ISBN 1-4931-0810-7.

- ^ Liddell & Scott; Code of Justinian Archived July 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine: "We direct that all Catholic churches, throughout the entire world, shall be placed under the control of the orthodox bishops who have embraced the Nicene Creed."

- ^ Jostein Ådna (editor), The Formation of the Early Church (Mohr Siebeck 2005 ISBN 978-316148561-9), p. 342