Our Friends in the North

| Our Friends in the North | |

|---|---|

Opening title sequence of Our Friends in the North. | |

| Genre | Serial drama |

| Written by | Peter Flannery |

| Directed by | Simon Cellan Jones Pedr James Stuart Urban |

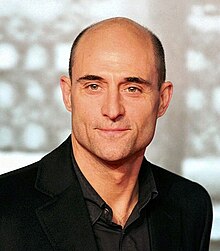

| Starring | Christopher Eccleston Gina McKee Daniel Craig Mark Strong |

| Composer | Colin Towns |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Original language | English |

| No. of series | 1 |

| No. of episodes | 9 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Producer | Charles Pattinson |

| Camera setup | Single camera |

| Running time | circa 70 minutes (each) |

| Original release | |

| Network | BBC Two |

| Release | 15 January – 11 March 1996 |

Our Friends in the North is a British television drama serial produced by the BBC. It was originally broadcast in nine episodes on BBC Two in early 1996. Written by Peter Flannery, it tells the story of four friends from the city of Newcastle upon Tyne in North East England over a period of 31 years, from 1964 to 1995. The story makes reference to certain political and social events which occurred during the era portrayed, some specific to Newcastle and others which affected Britain as a whole. These events include general elections, police and local government corruption, the UK miners' strike (1984–1985) and the Great Storm of 1987.

The serial is commonly regarded as one of the most successful BBC television dramas of the 1990s, described by The Daily Telegraph as "a production where all ... worked to serve a writer's vision. We are not likely to look upon its like again."[1] It has been named by the British Film Institute as one of the 100 Greatest British Television Programmes of the 20th century,[2] by The Guardian newspaper as the third greatest television drama of all time,[3] and by the Radio Times magazine as one of the 40 greatest television programmes.[4] It was awarded three British Academy Television Awards (BAFTAs), two Royal Television Society Awards, four Broadcasting Press Guild Awards, and a Certificate of Merit from the San Francisco International Film Festival.[5]

Our Friends in the North helped to establish the careers of its four lead actors, Daniel Craig, Christopher Eccleston, Gina McKee and Mark Strong. Daniel Craig's part in particular has been referred to as his breakthrough role.[6][7] It was also a controversial production, as its stories were partly based on real people and events. Several years passed before it was adapted from a play, performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company, to a television drama, due in part to the BBC's fear of litigation.

Plot

Each of the nine episodes of the serial takes place in the year for which it is named; 1964, 1966, 1967, 1970, 1974, 1979, 1984, 1987, and 1995. The episodes follow the four main characters and their changing lives, careers and relationships against the backdrop of the political and social events in the United Kingdom at the time.

The four friends are Dominic 'Nicky' Hutchinson (played by Christopher Eccleston), Mary Soulsby (Gina McKee), George 'Geordie' Peacock (Daniel Craig) and Terry 'Tosker' Cox (Mark Strong). The series begins in 1964. Nicky returns from working with the civil rights movement in the southern United States to resume his studies at the University of Manchester. He is reunited with his girlfriend, Mary, and best friend, Geordie, who is hoping to form a pop group with his mate Tosker.

Nicky is persuaded to drop out of university and work for corrupt local politician Austin Donohue (Alun Armstrong), swayed by Donohue's apparent idealism and desire to change Newcastle for the better. This is much to the annoyance of Nicky's trade unionist father Felix (Peter Vaughan), who does not want his son to waste opportunities that he never had when he was Nicky's age. Nicky's relationship with Mary ends when she becomes pregnant by Tosker and later marries him, which means she also drops out of university. On the run from a pregnant girlfriend himself and his abusive alcoholic father, Geordie leaves for London, where he falls in with seedy underworld baron Benny Barrett (Malcolm McDowell).

Geordie is initially successful while employed by Barrett in his Soho nightclubs and sex shops. He also helps Tosker and Mary by introducing Tosker to Barrett, who lends him the money to start his own fruit and vegetable business. Tosker's former dreams of musical stardom gradually fade away. Meanwhile, Nicky realises the extent of Donohue's corrupt dealings with building contractor John Edwards (Geoffrey Hutchings). He resigns in disgust, eventually becoming involved with left-wing anarchists in London.

By the early 1970s, the police have cracked down on Barrett's business and their own corruption, but not before Barrett has set Geordie up, sending him to prison in retaliation for an affair that Geordie had with Barrett's lover. Nicky's anarchist cell is raided, and he returns to Newcastle. Eventually Geordie returns as well. By 1979, Nicky has returned to more mainstream politics and stands for the Labour Party in the general election, but is defeated by the Conservative Party candidate (Saskia Wickham) after a smear campaign. Geordie leaves shortly before the election, not to be seen in the series again until 1987.

By 1984, Nicky is working as a successful photographer, and Mary has divorced Tosker, who has remarried and is rapidly becoming a rich businessman. Nicky and Mary renew their earlier relationship during the turbulent events of the miners' strike and eventually marry. By 1987, however, their marriage is falling apart. Nicky has an affair with a young student and is also forced to confront his father's Alzheimer's disease. He meets Geordie, now a homeless, drunken vagrant, by chance in London, but his old friend disappears before he has a chance to help him. Eventually Geordie is sentenced to life in prison as a danger to the public after setting fire to a mattress in a hostel. Despite her failing marriage to Nicky, Mary's life is becoming an increasing success, and she is now a councillor. Tosker, meanwhile, has lost his fortune in the stock market crash.

The final episode, 1995, sees Nicky, who has emigrated to Italy, returning to Newcastle to oversee the funeral of his mother. Tosker has managed to rebuild his business and is about to hold the opening night of his new floating nightclub, based on a boat moored on the River Tyne (filmed on the real club the Tuxedo Princess[8]). Mary, now a Labour Member of Parliament sympathetic to New Labour, is also invited to the opening, and Tosker is surprised to find Geordie back in the city as well; he has escaped from prison. Neither Mary nor Geordie make it to the opening night party, but the four friends are reunited the following day at Nicky's house after his mother's funeral. Tosker leaves to be with his grandchildren, and Mary leaves after agreeing to meet Nicky for lunch the next day. However, a desperate Nicky realises that "tomorrow's too late" and runs after Mary's car. He eventually attracts her attention and breathlessly asks, "Why not today?" to which she agrees, smiling. Meanwhile, Geordie walks off, and the series ends with him heading off into the distance across the Tyne Bridge after looking down at Tosker playing with his grandchildren on the boat below. As Geordie walks away and the credits fade up, the music of "Don't Look Back in Anger" by Oasis is heard.

Background

Stage play

Our Friends in the North was originally written by the playwright Peter Flannery for the theatre, while he was a writer in residence for the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC).[9] The idea came to Flannery while he was watching the rehearsals for the company's production of Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2 at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1980; the scale of the plays inspired him to come up with his own historical epic.[9] The original three-hour long theatre version of Our Friends in the North, directed by John Caird and featuring Jim Broadbent and Roger Allam among the cast, was produced by the RSC in 1982. It initially ran for a week at The Other Place in Stratford before touring to the city in which it was set, Newcastle upon Tyne, and then playing at The Pit, a studio theatre in the Barbican Centre in London.[10] In its original form, the story went up only to the 1979 general election and the coming to power of the new Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher.[11] The play also contained a significant number of scenes set in Rhodesia, chronicling UDI, the oil embargo and the emergence of armed resistance to white supremacy.[12] This plot strand was dropped from the televised version, although the title Our Friends in the North, a reference to how staff at BP in South Africa referred to the Rhodesian government of Ian Smith, remained.[13]

Flannery was heavily influenced not only by his own political viewpoints and life experiences, but also by the real-life history of his home city of Newcastle during the 1960s and 1970s.[14] Characters such as Austin Donohue and John Edwards were directly based on the real-life scandals of T. Dan Smith and John Poulson, who built cheap high-rise housing projects in Newcastle that they knew to be of low quality.[14] Flannery contacted Smith and explained that he was going to write a play based on the events of the scandal, to which Smith replied, "There is a play here of Shakespearean proportions."[15]

1980s attempts at production

The stage version of Our Friends in the North was seen by BBC television drama producer Michael Wearing in Newcastle in 1982, and he was immediately keen on producing a television adaptation.[16] At that time, Wearing was based at the BBC English Regions Drama Department at BBC Birmingham, which had a specific remit for making "regional drama", and had established his reputation by producing Alan Bleasdale's Boys from the Blackstuff in 1982.[17] Wearing initially approached Flannery to adapt his play into a four-part television serial for BBC Two, with each episode being 50 minutes long and the Rhodesian strand dropped for practical reasons.[18][19] A change of executives meant that the project did not reach production, however, Wearing persisted in trying to get it commissioned. Flannery extended the serial to six episodes,[18] one for each United Kingdom general election from 1964 to 1979.[20] However, by this point in the mid-1980s, Michael Grade was Director of Programmes for BBC Television, and he had no interest in the project.[21]

By 1989, Wearing had been recalled to the central BBC drama department in London where he was made Head of Serials.[22] This new seniority eventually allowed him to further the cause of Our Friends in the North. Flannery wrote to the BBC's then Managing Director of Television, Will Wyatt, "accusing him of cowardice for not approving it."[23] The BBC was concerned not only with the budget and resources that would be required to produce the serial, but also with potential legal issues. Much of the background story was based on real-life events and people, such as Smith and Poulson and former Home Secretary Reginald Maudling, upon whom another character, Claud Seabrook, was based.[24] According to The Observer newspaper, one senior BBC lawyer, Glen Del Medico, even threatened to resign if the production was made. Others tried to persuade Flannery to reset the piece "in a fictional country called Albion rather than Britain."[23] Both Smith and Poulson died before the programme aired.[25]

Pre-production

In 1992, Wearing was able to persuade the then-controller of BBC Two, Alan Yentob, to commission Peter Flannery to write scripts for a new version of the project.[21] However, Yentob had no great enthusiasm for Our Friends in the North, as he remembered a meeting with Flannery in 1988, when the writer had left him unimpressed by stating that Our Friends in the North was about "post-war social housing policy."[21][26] As Wearing was now a head of department at the BBC he was too busy overseeing other projects to produce Our Friends in the North personally.[27] George Faber was briefly attached to the project as producer before he moved on to become Head of Single Drama at the BBC.[27] Faber was succeeded by a young producer with great enthusiasm for the project, Charles Pattinson.[28]

When Yentob was succeeded as controller of BBC Two by Michael Jackson, Pattinson was able to persuade Jackson to commission full production on the series.[29] This was in spite of the fact that Jackson and Wearing were not close and did not get on; Pattinson took to dealing with Jackson directly.[21] Jackson had agreed to nine one-hour episodes, but Flannery protested that each episode should be as long as it needed to be, to which Jackson agreed.[29] The long delay in production did have the advantageous side effect of allowing Flannery to extend the story, and instead of ending in 1979, it now carried on into the 1990s, bringing the four central characters into middle age.[30] Flannery later commented that: "The project has undoubtedly benefited from the delay. I'm not sure I have."[29]

The series did encounter further legal problems when some references to the fictional businessman Alan Roe were removed because of a perceived similarity to Sir John Hall, a Newcastle businessman who had a number of factors in common. The drama had originally shown Roe as taking advantage of tax breaks to build a large shopping centre.[25]

Production and broadcast

The scale of Our Friends in the North required BBC Two controller Michael Jackson to devote a budget of £8 million to the production, which was half of his channel's drama serials budget for the entire year.[31] Producer Charles Pattinson attempted to gain co-production funding from overseas broadcasters, but none was interested. Pattinson believed it was because the story was so much about Britain and had limited appeal to other countries.[32] BBC Worldwide, the corporation's commercial arm which sells its programmes overseas, offered only £20,000 of funding towards the production.[32] The speaking cast of Our Friends in the North numbered 160;[23] more than 3,000 extras were used,[23] and filming took place across 40 weeks, from November 1994 until September 1995.[33]

Directors

The first director approached to helm the production by Michael Wearing was Danny Boyle.[34] Boyle was keen to direct all nine episodes, but Pattinson believed that one director taking charge of the entire serial would be too punishing a schedule for whomever was chosen.[35] Boyle had recently completed work on the feature film Shallow Grave and wanted to see how that film was received before committing to Our Friends in the North.[34] When Shallow Grave proved to be a critical success, Boyle was able to enter pre-production on Trainspotting. He withdrew from Our Friends in the North.[36] Sir Peter Hall was also briefly considered, but he too had other production commitments.[36]

Two directors were finally chosen to helm the project. Stuart Urban was assigned the first five episodes and Simon Cellan Jones the final four.[36] However, after completing the first two episodes and some of the shooting for the third, Urban left the project after disagreements with the production team.[37] Peter Flannery was concerned that Urban's directorial style was not suited to the material that he had written.[36] Christopher Eccleston's viewpoint is that Urban was "only interested in painting pretty pictures."[38] Pattinson agreed that a change was needed, and Michael Jackson agreed to a change of director mid-way through production, which was unusual for a British television drama of this type so far into proceedings.[37] Director Pedr James, who had recently directed an adaptation of Martin Chuzzlewit for Michael Wearing's department, was hired to shoot the remainder of what were to have been Urban's episodes.[37]

Casting

Of the actors cast in the four leading roles, only Gina McKee was a native of North East England, and she was from Sunderland rather than from Newcastle.[36] McKee related strongly to many of the characters and story elements in the scripts and was very keen to play Mary, but the production team was initially uncertain whether it would be possible to age her up convincingly enough to portray the character in her 50s.[39] McKee was concerned that she would not be given the part after an unsuccessful makeup test where efforts to make her appear to be in her 50s resulted in her resembling a drag queen.[39]

Christopher Eccleston was the only one of the four lead actors who was already an established television face, having previously co-starred in the ITV crime drama series Cracker.[36] Eccleston first heard about the project while working with Danny Boyle on the film Shallow Grave in the autumn of 1993.[38] Initially, Eccleston had been considered by the production team as a candidate to play Geordie, but he was more interested in playing Nicky, who he saw as a more emotionally complex character.[38] Eccleston was particularly concerned about being able to successfully perform with the Newcastle Geordie accent. He did not even attempt the accent at his audition, concentrating instead on characterisation.[38] He drew inspiration for his performance as the older Nicky from Peter Flannery himself, basing aspects of his characterisation on Flannery's personality. He even wore some of the writer's own colourful shirts.[38]

Daniel Craig was a late auditionee for the role of Geordie. At the audition, he performed the Geordie accent very poorly,[7] however, he won the part and it came to be regarded as his breakthrough role.[6][7] Mark Strong worked on the Geordie accent by studying episodes of the 1980s comedy series Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, which featured lead characters from Newcastle.[40] Strong later claimed that Christopher Eccleston took a dislike to him, and outside of their scenes together, the pair did not speak for the entire period that Our Friends in the North was filming.[40]

Among the supporting roles, one of the highest-profile pieces of casting was Malcolm McDowell as Soho porn baron Benny Barrett. Barrett appears in scenes across various episodes from 1966 through to 1979, but the production could only afford him for three weeks.[7] This was because McDowell was then a resident in the United States.[41] All of McDowell's scenes were therefore shot by Stuart Urban as part of the first block of filming, as opposed to the rest of the production which was filmed roughly chronologically.[35][37] This was considered more than worthwhile, however, for the prestige of being able to use an actor such as McDowell, predominantly a film actor who rarely did television work.[7][41]

It was Daniel Craig's performance in Our Friends in the North that first brought him to the attention of producer Barbara Broccoli, who later cast him in the role of secret agent James Bond in the long-running film series.[42] Christopher Eccleston also later went on to achieve notoriety in a cult screen role when he appeared as the Ninth Doctor in the BBC science-fiction series Doctor Who in 2005. Since then various media articles have noted the coincidence of the future James Bond and Doctor Who leads having co-starred in the same production earlier in their careers.[3][43][44][45]

Episode one remount

After Stuart Urban left the production and the decision had been made to re-shoot some of the material that he had completed with Pedr James directing, producer Charles Pattinson suggested to Peter Flannery that the first episode should not simply be remade, but also rewritten.[46] Flannery took the opportunity to completely change the opening storyline, introducing the love story element between Nicky and Mary earlier. This was introduced in later episodes of the television version, but had not been part of the original play.[46] Other storyline and character changes were made with the new version of the first episode because it was the script that had most closely resembled the original stage play. Michael Wearing felt that the story could be expanded to a greater degree for television.[34]

Production of the new version of the opening episode took place in what was to have been a three-week break for the cast between production blocks.[39] Gina McKee was initially very concerned about having her character's early life story changed when she had already based elements of her later performance on the previously-established version.[39] Eccleston was also unhappy about the sudden changes.[46] However, McKee felt that the new version of episode one eventually made for a much stronger opening to the story.[39]

Due to budgetary constraints, the production was not able to shoot the remounted scenes of episode one in the north-east, and they instead had to be filmed in and around Watford.[37] Beach-set scenes were shot at Folkestone rather than Whitley Bay, which was obvious to locals on screen due to the presence of pebbles on the beach, which are not present at Whitley.[47] This led to some critics mockingly referring to the production as Our Friends in the South.[47]

Music

Contemporary popular music was used throughout the production to evoke the feel of the year in which each episode was set.[48] The BBC's existing agreements with various music publishers and record labels meant that the production team was easily able to obtain the rights to use most of the desired songs.[48] A particular piece of synchronicity occurred in the final episode, 1995, which Cellan Jones had decided to close with the song "Don't Look Back in Anger" by Oasis.[41] While the serial was in production, it was just another track from their (What's the Story) Morning Glory? album. However, during transmission of Our Friends in the North, it was released as a single, and to Cellan Jones's delight, it was at the top of the UK Singles Chart in the week of the final episode's transmission.[41]

Broadcast

Our Friends in the North was broadcast in nine episodes on BBC Two at 9pm on Monday nights, from 15 January to 11 March 1996.[49] The episode lengths varied, with 1966 being the shortest at 63 minutes, 48 seconds and 1987 the longest at 74 minutes, 40 seconds.[33] The total running time of the serial is 623 minutes.[50]

The first episode of Our Friends in the North gained 5.1 million viewers on its original transmission,[51] and the first six episodes each gained between 4.5 and 5.5 million viewers.[52] In terms of viewing figures, the series became BBC Two's most successful weekly drama for five years.[53]

Reception

Critical response

Both during and after its original transmission on BBC Two, the serial was generally praised by the critics. Reviewing the first episode in The Observer newspaper, Ian Bell wrote: "Flannery's script is faultless; funny, chilling, evocative, spare, linguistically precise. The four young friends about to share 31 hellish years in the life of modern Britain are excellently played."[54]

The conclusion of the serial in March brought similar praise. "Our Friends in the North confounded the gloomier predictions about its content and proved that there was an audience for political material, provided that it found its way to the screen through lives imagined in emotional detail ... It will be remembered for an intimate sense of character, powerful enough to make you forgive its faults and stay loyal to the end,"[31] was the verdict of The Independent on the final episode. Writing in the same newspaper the following day, Jeffrey Richards added that "Monday night's final episode of Our Friends in the North has left many people bereft. The serial captivated much of the country, sketching a panoramic view of life in Britain from the sixties to the nineties ... At once sweeping and intimate, both moving and angry, simultaneously historical and contemporary, it has followed in the distinguished footsteps of BBC series such as Boys from the Blackstuff."[55]

However, the response was not exclusively positive. In The Independent on Sunday, columnist Lucy Ellmann criticised both what she saw as the unchanging nature of the characters and Flannery's concentration on friendship rather than family. "What's in the water there anyway? These are the youngest grandparents ever seen! Nothing has changed about them since 1964 except a few grey hairs ... It's quite impressive that anything emotional could be salvaged from this nine-part hop, skip and jump through the years. In fact we still hardly know these people – zooming from one decade to the next has a distancing effect,"[56] she wrote of the former point. And of the latter, "Peter Flannery seems to want to suggest that friendships are the only cure for a life blighted by deficient parents. But all that links this ill-matched foursome in the end is history and sentimentality. The emotional centre of the writing is still in family ties."[56]

Michael Jackson, the BBC Two controller who had finally commissioned production of the serial, felt that even though it was successful, its social realist form was outdated.[57] The academic Georgina Born, writing in 2004, also felt that although the serial had its strengths, it also contained "involuntary marks of pastiche" in its treatment of social realism.[57]

In contrast, the British Film Institute's Screenonline website praises the serial for its realistic and un-clichéd depiction of life in the North East England, stating that: "Unlike many depictions of the North-East, it has fully rounded characters with authentic regional accents. It's clearly a real place, not a generic 'up North'."[30]

Awards and recognition

At the British Academy Television Awards (BAFTAs) in 1997, Our Friends in the North won the award for Best Drama Serial, ahead of other nominees The Crow Road, The Fragile Heart and Gulliver's Travels.[58] At the same ceremony, Gina McKee won the Best Actress category.[59] Both Christopher Eccleston and Peter Vaughan (who played Nicky's father, Felix) were nominated for the Best Actor award for their performances in Our Friends in the North, but they lost to Nigel Hawthorne for his role in The Fragile Heart.[60] Also at the 1997 BAFTAs, Peter Flannery was presented with the honorary Dennis Potter Award for his work on the serial.[61] Our Friends in the North also gained BAFTA nominations for costume design, sound, and photography and lighting.[5]

The Royal Television Society Awards covering the year 1996 saw Our Friends in the North win the Best Drama Serial category, and Peter Flannery was given the Writer's Award.[62] Peter Vaughan also gained another Best Actor nomination for his role as Felix.[5] At the 1997 Broadcasting Press Guild Awards, Our Friends in the North won the categories for Best Drama Series or Serial, Best Actor (Eccleston), Best Actress (McKee) and the Writer's Award for Peter Flannery.[63]

In the United States, Our Friends in the North was awarded a Certificate of Merit in the Television Drama Miniseries category at the San Francisco International Film Festival in 1997.[5]

In 2000, the British Film Institute conducted a poll of industry professionals to find the 100 Greatest British Television Programmes of the 20th century, with Our Friends in the North finishing in twenty-fifth position, eighth position out of the dramas featured on the list. The commentary for the Our Friends in the North entry on the BFI website described it as a "powerful and evocative drama series ... The series impressed with its ambition, humanity and willingness to see the ambiguities beyond the rhetoric."[2] The serial was also included in an alphabetical list of the 40 greatest TV shows published by the Radio Times magazine in August 2003, chosen by their television editor Alison Graham.[4][64] In January 2010, the website of The Guardian newspaper produced a list of "The top 50 TV dramas of all time," in which Our Friends in the North was ranked in third position.[3]

Legacy

Following the success of Our Friends in the North, Flannery proposed a "kind of prequel" to the serial under the title of Our Friends in the South.[65] This would have told the story of the Jarrow March.[66] Although the BBC initially took up the project, it did not progress to script stage and was eventually abandoned.[65][66]

Our Friends in the North was given a repeat run on BBC Two the year following its original broadcast, running on Saturday evenings from 19 July to 13 September 1997.[67][68] It received a second repeat run on the BBC ten years after its original broadcast, running on BBC Four from 8 February to 29 March 2006.[67][68] In the early 2000s, the serial was also repeated on the UK Drama channel.[69]

In April 1997, the serial was released on VHS by BMG Video in two separate sets, 1964 – 1974 and 1979 – 1995.[70][71] In 2002, BMG released the complete series on DVD, which along with the original episodes contained several extra features, including a retrospective discussion of the series by Wearing, Pattinson, Flannery, James and Cellan Jones, and specially shot interviews with Eccleston and McKee.[72] Simply Media brought out a second DVD release of the serial in September 2010, although on this occasion there were no extra features.[73] This edition contained an edit not present on the 2002 BMG release; most of the song "Don't Look Back In Anger" by Oasis is removed at the end of the final episode, fading out early and the credits instead running in silence.[73]

Our Friends in the North has been invoked on several occasions as a comparison when similar drama programmes have been screened on British television. The year following Our Friends in the North's broadcast, Tony Marchant's drama serial Holding On was promoted by the BBC as being an "Our Friends in the South," after Marchant made the comparison when discussing it with executives.[74] The 2001 BBC Two drama serial In a Land of Plenty was previewed by The Observer newspaper as being "the most ambitious television drama since Our Friends in the North."[75] The writer Paula Milne drew inspiration from Our Friends in the North for her own White Heat (2012); she felt that Our Friends in the North had been too centred on white, male, heterosexual characters, and she deliberately wanted to counter that focus.[76]

The original stage version of Our Friends in the North was revived in Newcastle by Northern Stage in 2007, with 14 cast members playing 40 characters.[77][78]

In August 2016, Flannery was interviewed for an event, part of the Whitley Bay Film Festival, that celebrated the 20th anniversary of the series being broadcast.[79]

References

- Eaton, Michael (2005). Our Friends in the North. BFI TV Classics. London: British Film Institute. ISBN 1844570924.

- Born, Georgina (2004). Uncertain Vision: Birt, Dyke and the Reinvention of the BBC. London: Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0436205629.

Notes

- ^ Unknown. The Daily Telegraph. Quoted on the DVD release cover. (BMG DVD 74321 941149)

- ^ a b Wickham, Phil (2000). "BFI TV 100 – 25: Our Friends in the North". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ a b c "The top 50 TV dramas of all time: 2–10". The Guardian. 12 January 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Classic comedy drama voted TV's greatest". The Daily Telegraph. 27 August 2003. Retrieved 2 September 2003.

- ^ a b c d "Awards for Our Friends in the North". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Daniel Craig: Our friend in MI6". BBC Online. 14 October 2005. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Raphael, Amy (18 September 2010). "Our Friends In The North made a star of Daniel Craig but almost wasn't made". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ "Tuxedo Princess – the floating nightclub". Inside Out. BBC. 8 August 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ a b Eaton, p. 2

- ^ Eaton, p. 8

- ^ Eaton, p. 121

- ^ Eaton, p. 6

- ^ Eaton, p. 7

- ^ a b Eaton, pp. 4–5

- ^ Flannery, Peter (2002). Retrospective: An Interview with the Creators of the Series (DVD). BMG. BMG DVD 74321.

- ^ Eaton, p. 9

- ^ Eaton, p. 12

- ^ a b Born, p. 357

- ^ Eaton, p. 13

- ^ Eaton, p. 14

- ^ a b c d Born, p. 358

- ^ Cooke, Lez. "Wearing, Michael (1989–)". Screenonline. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d Brooks, Richard (1 January 1996). "Friends come in from the BBC cold". The Guardian. p. 7.

- ^ Eaton, p. 65

- ^ a b Hellen, Nicholas (3 December 1995). "BBC cuts drama over legal fears". Sunday Times. p. 1.

- ^ Eaton, p. 18

- ^ a b Eaton, p. 21

- ^ Eaton, p. 23

- ^ a b c Eaton, pp. 24–25

- ^ a b Hackston, Ronald. "Our Friends in the North". Screenonline. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ a b Sutcliffe, Thomas (12 March 1996). "Our Friends in the North (BBC2)". The Independent. p. 24.

- ^ a b Born, p. 359

- ^ a b Eaton, p. 130

- ^ a b c Wearing, Michael (2002). Retrospective: An Interview with the Creators of the Series (DVD). BMG. BMG DVD 74321.

- ^ a b Eaton, p. 26

- ^ a b c d e f Eaton, p. 27

- ^ a b c d e Eaton, pp. 28–29

- ^ a b c d e Eccleston, Christopher (2002). Interview with Christopher Eccleston (DVD). BMG. BMG DVD 74321.

- ^ a b c d e McKee, Gina (2002). Peter Flannery interviews Gina McKee (DVD). BMG. BMG DVD 74321.

- ^ a b Thompson, Ben (25 February 1996). "The Interview: Mark Strong talks to Ben Thompson". The Independent. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d Cellan Jones, Simon (2002). Retrospective: An Interview with the Creators of the Series (DVD). BMG. BMG DVD 74321.

- ^ Weiner, Juli (November 2012). "Bond Ambition". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ Mulkerrins, Jane (17 June 2013). "The Borgias star Gina McKee: The fear of shame is a really good motivator". Metro. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ "Daniel Craig". BBC Online. May 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ Petrie, Andrew (30 October 2010). "Friends indeed". The Spectator. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Eaton, p. 30

- ^ a b Eaton, p. 33

- ^ a b Pattinson, Charles (2002). Retrospective: An Interview with the Creators of the Series (DVD). BMG. BMG DVD 74321.

- ^ "BBC Two – Our Friends in the North". BBC Online. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ Williams, Zoe (27 March 2009). "Your next box set: Our Friends in the North". Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ "BBC drama gains on ITV". The Times. 7 February 1996. p. 23.

- ^ Paterson, Peter (12 March 1996). "Peter was the Best of Friends". Daily Mail. p. 57.

- ^ Culf, Andrew (19 February 1996). "A range of options". The Guardian. p. 16.

- ^ Bell, Ian (21 January 1996). "A Brief History of Tyne". The Independent. p. 18.

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey (13 March 1996). "The BBC's voice of two nations". The Independent. p. 15. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ a b Ellmann, Lucy (17 March 1996). "With Friends Like These...". Independent on Sunday. p. 12.

- ^ a b Born, p. 356

- ^ "Television – Drama Serial in 1997". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Television – Actress in 1997". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Television – Actor in 1997". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Television – Dennis Potter Award in 1997". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Awards Archive February 2011" (PDF). Royal Television Society. February 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Broadcasting Press Guild Awards – Awards for 1997". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Top 40 TV shows". The Daily Telegraph. 27 August 2003. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ a b "The Devil's Whore mixes fact with fiction". Shields Gazette. 14 November 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

I wanted to do Our Friends in the South for the BBC, which would have been a kind of prequel to Our Friends in the North, but it was never taken up, so it remained an idea only, with no actual play.

- ^ a b "Peter Flannery on..." Broadcast. 3 November 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

I wanted to do Our Friends in the South [about the Jarrow march], which the BBC took up. Its commitment was so lukewarm, there was really no point in continuing.

- ^ a b "BBC Two – Our Friends in the North, 1964". BBC Online. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ a b "BBC Two – Our Friends in the North, 1995". BBC Online. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Rampton, James (4 September 2002). "The Best of Satellite, Cable and Digital". The Independent. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Our Friends in the North: 1964–1974". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ "Our Friends in the North: 1979–1995". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ Eaton, p. 125.

- ^ a b Slarek (6 October 2010). "Our Friends in the North DVD review". Cine Outsider. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Dugdale, John (1 September 1997). "No cheeky chappies, East End villains or Docklands 'glamour'. Can this really be London?". The Guardian. p. 14.

Two years ago, Tony Marchant made a fatal mistake. Outlining his plans for an ambitious, layered portrait of London to BBC drama execs, he 'tried to explain its scope with a joke, calling it 'Our Friends In The South'. Looking back, I'm not sure I should've done.' Probably not: BBC high-ups and publicists routinely use the tag when enthusing about Marchant's coruscating new series.

- ^ Lane, Harriet (17 December 2000). "From famine to feast..." The Observer. p. 9. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Milne, Paula (7 March 2012). "Paula Milne on what inspired her to write White Heat". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

The focus of Our Friends primarily lay with the social and political events shaping the destinies of its white male heterosexual characters. The contraceptive pill, legalizing abortion, the emergent sexual revolution, racial tension, feminism and gay rights were also part of the second half of the twentieth century, and it was these that I wanted to explore as well with White Heat – to see how they too shaped the lives of those of us who had lived through them.

- ^ "Our Friends in the North". BBC Online. 26 September 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ Walker, Lynne (27 September 2007). "Tyne and again". The Independent. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Armstrong, Simon (27 August 2016). "Our Friends in the North: What made it so special?". BBC News. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

External links

- 1990s British drama television series

- 1996 British television programme debuts

- 1996 British television programme endings

- BBC television dramas

- British television miniseries

- Serial drama television series

- English-language television programming

- Television series set in the 1960s

- Television series set in the 1970s

- Television series set in the 1980s

- Television shows set in Tyne and Wear

- Television shows set in Newcastle upon Tyne

- Films directed by Stuart Urban