Palais Leuchtenberg

The Palais Leuchtenberg, (known between 1853 and 1933 as the Luitpold Palais or Prinz Luitpold Palais[1]) built in the early 19th century for Eugène de Beauharnais, first Duke of Leuchtenberg, is the largest palace in Munich. Located on the west side of the Odeonsplatz (Odeon Square), where it forms an ensemble with the Odeon, it currently houses the Bavarian State Ministry of Finance. It was once home to the Leuchtenberg Gallery on the first floor.

History

Palace by Leo von Klenze

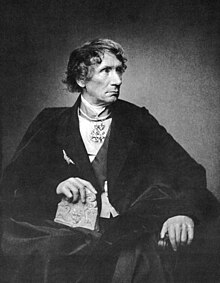

Eugène de Beauharnais, the brother-in-law of the later King Ludwig I of Bavaria and the stepson of Napoleon, commissioned Leo von Klenze to build a "suburban city palace". Constructed between 1817 and 1821 at a cost of 770,000 guilders (the entire construction budget for Bavaria in 1819), it was the largest palace of the era, with more than 250 rooms including a ballroom, a theatre, a billiard room, an art gallery, and a chapel, plus a number of outbuildings extending for over 100 metres (110 yd) down what is now Kardinal-Döpfner-Straße.[2] It was the first building on the Ludwigstraße. Klenze intended it to serve as a benchmark for the new boulevard. He chose the Italian neo-Renaissance style, modelling the building on the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. He placed eagles over the windows on the first floor as in one of Napoleon's palaces.[2] He gave the building almost equally prominent façades on three sides, and a sufficiently adaptable interior layout for it to be repurposed in case Beauharnais was forced by Ludwig to leave Munich.[2] It had two floors above the ground floor and each floor had 11 windows. Also notable was a small entrance porch or portico of Doric type with four columns. The concert hall or ball room was very large measuring 124 ft in length and 71 ft in width with a height of 50 ft.[3]

Klenze also visited Paris during the construction phase to study the newly developed fosses inodores et mobiles (an early form of sanitary toilet), which he had installed in the palace and which soon became standard in almost all new buildings in Munich.

Beauharnais lived in the palace with his wife Augusta, Ludwig's sister, and his children. On 2 August 1829 the proxy marriage of Emperor Pedro I of Brazil and Princess Amélie of Leuchtenberg took place in the chapel. Court festivities were a feature in the palace in view of its ballroom, art gallery and a private theater facilities.[2]

In 1852, after the death of Eugène de Beauharnais' widow Augusta, the palace was sold to Prince Luitpold, the later Prince Regent of Bavaria.,[4] and until the Nazi seizure of power early in 1933, it was used by the Bavarian royal family, the House of Wittelsbach.

Prince Ludwig, later Ludwig III, married Maria Theresia, Archduchess of Austria-Este in 1868 and it was their first home. Their son Prince Rupprecht was born here in 1869 and was baptised in the palace chapel on May 20, 1869.[1]

After the end of the monarchy in Bavaria in 1918, the outbuildings were converted into shops and a garage.[4] In 1923, the Bavarian Landtag approved the private ownership of the palace. Rupprecht, who had relocated here from the Palais Leutstetten with his son, Albrecht von Bayern, when they were challenged by Adolf Hitler as he came to power,[5] lived there until 1939[1] in a small apartment, sometimes using the reception rooms for events.[4]

During the Second World War, the palace was badly damaged in air raids in 1943 and 1945. The Free State of Bavaria acquired the ruined building in 1957 and had it demolished.[4]

Heid and Simm building

In 1963–1967, a new building designed by Hans Heid and Franz Simm was built on the site for the Bavarian State Ministry of Finance. This building has a frame of reinforced concrete with brick facing. The façade is an accurate reconstruction of von Klenze's palace except for a new entrance on the east side; the main entrance was formerly on the south side.[2] (The only actual old fabric retained is the west entrance.)[6] However, the interior layout has not been reproduced, although the ministry reception rooms and the office of the State Minister of Finance are located on the first floor, the bel étage. What little survived of the ornate interior of the former building is now in Nymphenburg Palace.[1] The Alexander frieze by Bertel Thorvaldsen survives only in a copy which is now in the foyer of the Herkulessaal (Hercules Hall), a post-war concert hall in the Residenz.

In 1958 the architect and preservationist Erwin Schleich had suggested reconstructing the destroyed Odeon concert hall on the site of the Palais Leuchtenberg, since the concert hall could not be rebuilt on its original site. Although this plan had some support, it was not carried out.[7]

References

- ^ a b c d McFerran, Noel S. (1 November 2003). "A Jacobite Gazetteer - Bavaria". Jacobite.ca. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Das Palais Leuchtenberg, Bavarian State Ministry of Finance Template:De icon

- ^ Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain) (1839). Penny cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. C. Knight. pp. 484–.

- ^ a b c d Das Palais Leuchtenberg: Vom Stadtpalais zum Finanzministerium, Bavarian State Ministry of Finance Template:De icon

- ^ Donohoe, James (1961). Hitler's Conservative Opponents in Bavaria, 1930-1945: A Study of Catholic, Monarchist, and Separatist Anti-Nazi Activities. E. J. Brill. p. 109. OCLC 1987951.

- ^ Gavriel David Rosenfeld, Munich and Memory: Architecture, Monuments, and the Legacy of the Third Reich, Weimar and now 22, Berkeley: University of California, 2000, ISBN 9780520219106, [books.google.com/books?id=VHLfb3kljBwC&pg=368 p. 368, n. 7].

- ^ Rosenfeld, p. 190.