Peace dollar

United States | |

| Value | 1 United States dollar |

|---|---|

| Mass | 26.73 g (412.5 gr) |

| Diameter | 38.1 mm (1.5 in) |

| Edge | reeded |

| Composition | |

| Silver | 0.77344 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1921–1928; 1934–1935 |

| Mint marks | D, S. Located above tip of eagle's wings on reverse. Philadelphia Mint specimens lack mint mark. |

| Obverse | |

| Design | Liberty |

| Designer | Anthony de Francisci |

| Design date | 1921 |

| Reverse | |

| Design | A perched bald eagle |

| Designer | Anthony de Francisci |

| Design date | 1921 |

The Peace dollar is a United States dollar coin minted from 1921 to 1928, and again in 1934 and 1935. Designed by Anthony de Francisci, the coin was the result of a competition to find designs emblematic of peace. Its obverse represents the head and neck of the Goddess of Liberty in profile, and the reverse depicts a bald eagle at rest clutching an olive branch, with the legend "Peace". It was the last United States dollar coin to be struck for circulation in silver.

With the passage of the Pittman Act in 1918, the United States Mint was required to strike millions of silver dollars, and began to do so in 1921, using the Morgan dollar design. Numismatists began to lobby the Mint to issue a coin that memorialized the peace following World War I; although they failed to get Congress to pass a bill requiring the redesign, they were able to persuade government officials to take action. The Peace dollar was approved by Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon in December 1921, completing the redesign of United States coinage that had begun in 1907.

The public believed the announced design, which included a broken sword, was illustrative of defeat, and the Mint hastily acted to remove the sword. The Peace dollar was first struck on December 28, 1921; just over a million were coined bearing a 1921 date. When the Pittman Act requirements were met in 1928, the mint ceased to strike the coins, but more were struck in 1934 and 1935 as a result of other legislation. In 1965, the mint struck over 300,000 Peace dollars bearing a 1964 date, but these were never issued, and all are believed to have been melted.

Background and preparations

Statutory history

The Bland–Allison Act, passed by Congress on February 28, 1878, required the Treasury to purchase a minimum of $2 million in domestically mined silver per month and coin it into silver dollars.[1] The Mint used a new design by engraver George T. Morgan, and struck what became known as the Morgan dollar. Many of the pieces quickly vanished into bank vaults for use as backing for paper currency redeemable in silver coin, known as silver certificates. In 1890, the purchases required under the Bland–Allison Act were greatly increased under the terms of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Although the Sherman Act was repealed in 1893, it was not until 1904 that the government struck the last of the purchased silver into dollars. Once it did, production of the coin ceased.[2]

During World War I, the German government hoped to destabilize British rule over India by spreading rumors that the British were unable to redeem for silver all of the paper currency they had printed.[2] These rumors, and hoarding of silver, caused the price of silver to rise and risked damaging the British war effort.[2] The British turned to their war ally, the United States, asking to purchase silver to increase the supply and lower the price. In response, Congress passed the Pittman Act of April 23, 1918. This statute gave the United States authority to sell metal to the British government from up to 350,000,000 silver dollars at $1 per ounce of silver plus the value of the copper in the coins, and handling and transportation fees. Only 270,232,722 coins were melted for sale to the British, but this represented 47% of all Morgan dollars struck to that point.[3] The Treasury was required by the terms of the Act to strike new silver dollars to replace the coins that were melted, and to strike them from silver purchased from American mining companies.[4]

Idea and attempted legislation

It is uncertain who originated the idea for a US coin to commemorate the peace following World War I; the genesis is usually traced to an article by Frank Duffield published in the November 1918 issue of The Numismatist. Duffield suggested that a victory coin should be "issued in such quantities it will never become rare".[5] In August 1920, a paper by numismatist Farran Zerbe was read to that year's American Numismatic Association (ANA) convention in Chicago.[6] In the paper, entitled Commemorate the Peace with a Coin for Circulation, Zerbe called for the issuance of a coin to celebrate peace, stating,

I do not want to be misunderstood as favoring the silver dollar for the Peace Coin, but if coinage of silver dollars is to be resumed in the immediate future, a new design is probable and desirable, bullion for the purpose is being provided, law for the coinage exists and limitation of the quantity is fixed—all factors that help pave the way for Peace Coin advocates. And then—we gave our silver dollars to help win the war, we restore them in commemoration of victory and peace.[7]

Zerbe's proposal led to the appointment of a committee to transmit the proposal to Congress and urge its adoption.[6] According to numismatic historian Walter Breen, "Apparently, this was the first time that a coin collector ever wielded enough political clout to influence not only the Bureau of the Mint, but Congress as well."[8] The committee included noted coin collector and Congressman William A. Ashbrook (Democrat–Ohio), who had chaired the House Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures until the Republicans gained control following the 1918 elections.[8]

Ashbrook was defeated for re-election in the 1920 elections; at that time congressional terms did not end until March 4 of the following year. He was friendly with the new committee chairman Albert Henry Vestal (Republican–Indiana), and persuaded him to schedule a hearing on the peace coin proposal for December 14, 1920. Though no bill was put before it, the committee heard from the ANA delegates, discussed the matter, and favored the use of the silver dollar, which as a large coin had the most room for an artistic design.[9] The committee took no immediate action; in March 1921, after the Harding administration took office, Vestal met with the new Secretary of the Treasury, Andrew W. Mellon, and Mint Director Raymond T. Baker about the matter, finding them supportive so long as the redesign involved no expense.[10]

On May 9, 1921, striking of the Morgan dollar resumed at the Philadelphia Mint under the recoinage called for by the Pittman Act. The same day, Congressman Vestal introduced the Peace dollar authorization bill as a joint resolution.[11] Vestal placed his bill on the Unanimous Consent Calendar, but Congress adjourned for a lengthy recess without taking any action.[6] When Congress returned, Vestal asked for unanimous consent that the bill pass on August 1, 1921. However, one representative, former Republican leader James R. Mann (Illinois) objected, and numismatic historian Roger Burdette suggests that Mann's stature in the House ensured that the bill would not pass.[12] Nevertheless, Vestal met with the ANA and told them that he hoped Congress would reconsider when it met again in December 1921.[12]

Competition

Sometime after the December 1920 hearing requested by the ANA, the chairman of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, Charles Moore, became aware of the proposed congressional action, and decided to investigate.[10] Moore, together with Commission member and Buffalo nickel designer James Earle Fraser, met with Mint Director Baker on May 26, 1921, and they agreed that it would be appropriate to hold a design competition for the proposed dollar, under the auspices of the Commission. This was formalized on July 26 with the Commission's written recommendation to the Mint that a competition, open only to invited sculptors, be used to select designs.[13] The winner of the competition was to receive $1,500 prize money, while all other participants would be given $100.[14] On July 28, President Harding issued Executive Order 3524, requiring that coin designs be submitted to the Commission before approval by the Treasury Secretary.[15] In early September, following the failure of the bill, Baker contacted Moore, putting the matter aside pending congressional action.[13]

By November, proponents of the peace coin had realized that congressional approval was not necessary—as the Morgan dollar had been struck for more than 25 years, it was eligible for replacement at the discretion of the Secretary of the Treasury under an 1890 act.[16][17] The Morgan design was then being used for large quantities of silver dollars as the Mint struck replacements for the melted coins under the Pittman Act.[17] Though Congress had not yet convened, Baker contacted Fraser in early November to discuss details of the design competition. According to Burdette, Baker's newfound enthusiasm came from the fact that President Harding was about to formally declare an end to the war with Germany—a declaration needed because the US had not ratified the Treaty of Versailles. In addition, the Washington Conference on disarmament, for which the administration had great hopes, was soon to convene.[18] On November 19, Fraser notified competition participants by personal letter, sending official rules and requirements four days later, with submissions due by December 12.[19] Competition participants included Hermon MacNeil, Victor D. Brenner, and Adolph Weinman, all of whom had designed previous U.S. coins.[19]

The artists were instructed to depict the head of Liberty on the obverse, to be made "as beautiful and full of character as possible".[20] The reverse would depict an eagle, as prescribed by the Coinage Act of 1792, but otherwise was left to the discretion of the artist. The piece also had to bear the denomination, the name of the country, "E pluribus unum", the motto "In God We Trust", and the word "Liberty".[20]

On December 13, the commission assembled to review the submitted designs, as well as a set produced by Mint Chief Engraver Morgan at Baker's request, and a set, unrequested, from a Mr. Folio of New York City. It is not known how the designs were displayed for the Commission. After considerable discussion among Fraser, Moore, and Herbert Adams (a sculptor and former member of the Commission), a design by Anthony de Francisci was unanimously selected.[21]

Design

At age 34, de Francisci was the youngest of the competitors; he was also among the least experienced in the realm of coin design. While most of the others had designed regular or commemorative coins for the Mint, de Francisci's sole effort had been the conversion of drawings for the 1920 Maine commemorative half dollar to the finished design. De Francisci had had little discretion in that project, and later said of the work, "I do not consider it very favorably."[22]

The sculptor based the obverse design of Liberty on the features of his wife, Teresa de Francisci.[23] Due to the short length of the competition, he lacked the time to hire a model with the features he envisioned.[24] Teresa de Francisci was born Teresa Cafarelli in Naples, Italy. In interviews, she related that when she was five years old and the steamer on which she and her family were immigrating passed the Statue of Liberty, she was fascinated by the statue, called her family over, and struck a pose in imitation. She later wrote to her brother Rocco,

You remember how I was always posing as Liberty, and how brokenhearted I was when some other little girl was selected to play the role in the patriotic exercises in school? I thought of those days often while sitting as a model for Tony's design, and now seeing myself as Miss Liberty on the new coin, it seems like the realization of my fondest childhood dream.[23]

Breen wrote that the radiate crown that the Liberty head bears is not dissimilar to those on certain Roman coins, but is "more explicitly intended to recall that on the Statue of Liberty".[11] Anthony de Francisci recalled that he opened the window of the studio and let the wind blow on his wife's hair as he worked.[23] However, he did not feel that the design depicted her exclusively.[14] He noted that "the nose, the fullness of the mouth are much like my wife's, although the whole face has been elongated".[14] De Francisci submitted two reverse designs; one showed a warlike eagle, aggressively breaking a sword; the other an eagle at rest, holding an olive branch. The latter design, which would form the basis for the reverse of the Peace dollar, recalled de Francisci's failed entry for the Verdun City medal. The submitted obverse is almost identical to the coin as struck, excepting certain details of the face, and that the submitted design used Roman rather than Arabic numerals for the date.[25]

Baker, de Francisci, and Moore met in Washington on December 15. At that time, Baker, who hoped to start Peace dollar production in 1921, outlined the tight schedule for this to be accomplished, and requested certain design changes. Among these was the inclusion of the broken sword from the sculptor's alternate reverse design, to be placed under the eagle, on the mountaintop on which it stands, in addition to the olive branch. Baker approved the designs, subject to these changes.[26] The revised designs were presented to President Harding on December 19. Harding insisted on the removal of a small feature of Liberty's face, which seemed to him to suggest a dimple, something he did not consider suggestive of peace, and the sculptor then did so.[27]

Controversy

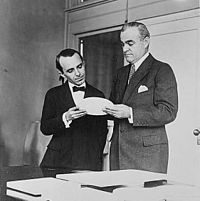

The Treasury announced the new design on December 19, 1921. Photographs of Baker and de Francisci examining the final plaster model appeared in newspapers, along with written descriptions of the designs, since the Treasury at that time took the position that it was illegal for photographs of a United States coin to be printed in a newspaper. Secretary Mellon gave formal approval to the design on December 20. As it would take the Mint several days to produce working dies, the first strike of the new coins was scheduled for December 29.[28]

The new design was widely reported in newspapers, and was the source of intense public attention. A Mint press release described the reverse as "a large figure of an eagle perched on a broken sword, and clutching an olive branch bearing the word, 'peace'".[29] On December 21, the New York Herald ran a scathing editorial against the new design,

If the artist had sheathed the blade or blunted it there could be no objection. Sheathing is symbolic of peace, of course; the blunted sword implies mercy. But a broken sword carries with it only unpleasant associations.

A sword is broken when its owner has disgraced himself. It is broken when a battle is lost and breaking is the alternative to surrendering. A sword is broken when the man who wears it can no longer render allegiance to his sovereign. But America has not broken its sword. It has not been cashiered or beaten; it has not lost allegiance to itself. The blade is bright and keen and wholly dependable. It is regrettable that the artist should have made such an error in symbolism. The sword is emblematic of Justice as well as of Strength. Let not the world be deceived by this new dollar. The American effort to limit armament and to prevent war or at least reduce its horror does not mean that our sword is broken.[30]

At the time, according to Burdette, given the traumas of the Great War, Americans were highly sensitive about their national symbols, and unwilling to allow artists any leeway in interpretation.[30] The Mint, the Treasury, and the Fine Arts Commission began to receive large numbers of letters from the public objecting to the design.[31] De Francisci attempted to defend his design, stating, "with the sword there is the olive branch of peace and the combination of the two renders it impossible to conceive of the sword as a symbolization of defeat".[32] Baker had left Washington to visit the San Francisco Mint, a transcontinental journey of three days. Acting Mint Director Mary Margaret O'Reilly sent him a telegram on December 23, urgently seeking his approval to remove the sword from the reverse, as had been recommended by Moore and Fraser at a meeting the previous afternoon. Due to the tight timeline for 1921 strikings of the dollar, it was not possible to await Baker's response, so on the authority of Treasury Undersecretary Seymour Parker Gilbert, who was approached by O'Reilly, the Mint proceeded with the redesign. To satisfy Harding's executive order, the Fine Arts Commission quickly approved the change, and by the time Baker wired his approval on December 24, without being able to see the revisions, Gilbert had already approved the revised design in Secretary Mellon's absence.[33] A press release was issued late on December 24, stating that the broken sword which had appeared on de Francisci's alternate reverse would not appear on the issued coin.[34] In its December 25 edition, the Herald took full credit for the deletion of the broken sword from the coin's design.[35]

Farran Zerbe, whose paper to the ANA convention helped launch the dollar proposal, saw de Francisci's defense and the press release, and suggested that the sculptor had mistakenly thought his alternate design had been approved.[36]

Production

Initial release

The removal of the sword from the coinage hub, which had already been produced by reduction from the plaster models, was accomplished by painstaking work by Mint Chief Engraver Morgan, using extremely fine engraving tools under magnification. Morgan did the work on December 23 in the presence of de Francisci, who had been summoned to the Philadelphia Mint to ensure the work met with his approval. It was insufficient merely to remove the sword, as the rest of the design had to be adjusted. Morgan had to hide the excision; he did so by extending the olive branch, previously half-hidden by the sword, but had to remove a small length of stem that showed to the left of the eagle's talons. Morgan also strengthened the rays, and sharpened the appearance of the eagle's leg. The chief engraver did his work with such skill that the work on the dollar was not known for over 85 years.[37]

On December 28, Philadelphia Mint Superintendent Freas Styer wired Baker in San Francisco, reporting the first striking of the Peace dollar. The Mint later reported that 1,006,473 pieces were struck in 1921, a rate of output for the four days remaining in the year that Burdette calls "amazing"; he speculates that minting of 1921 Peace dollars continued into 1922.[35] The first coin struck was to be sent to President Harding, but what became of it is something of a mystery: O'Reilly indicated that she had the coin sent to Harding, but the inventory of Harding's estate, prepared after the President died in office less than two years later, does not mention it, nor is there any mention of the coin in Harding's papers.[38] Breen, in his earlier book on U.S. coins, stated that the coin was delivered to Harding by messenger on January 3, 1922, but does not state the source of his information.[11] A few proofs of the 1921 production were struck early in the run, in both satin and matte finishes, but it is unknown exactly how many with either finish were created; numismatic historians Leroy Van Allen and A. George Mallis estimate the mintage totals at 24 of the former and five of the latter.[39]

The Peace dollar was released into circulation on January 3, 1922.[39] In common with all silver and copper-nickel dollar coins[40] struck from 1840 to 1978, the Peace dollar had a diameter of 1.5 inches (38 mm), which was larger than the Mint's subsequently struck modern dollar coins.[41][42][43][44] Its issuance completed the redesign of United States coinage that had begun with issues in 1907.[45] Long lines formed at the Sub-Treasury Building in New York the following day when that city's Federal Reserve Bank received a shipment; the 75,000 coins initially sent by the Mint were "practically exhausted" by the end of the day.[46] Rumors that the coins did not stack well were contradicted by bank cashiers, who demonstrated for The New York Times that the coins stacked about as well as the Morgan dollars.[46] De Francisci had paid Morgan for 50 of the new dollars; on January 3, Morgan sent him the pieces. According to his wife, de Francisci had bet several people that he would lose the design competition; he used the pieces to pay off the bets and did not keep any.[47]

According to one Philadelphia newspaper,

Liberty is getting younger. Take it from the new 'Peace Dollar,' put in circulation yesterday, the young woman who has been adorning silver currency for many years, never looked better than in the 'cart wheel' that the Philadelphia Mint has just started to turn out. The young lady, moreover, has lost her Greek profile. Helenic [sic] beauty seems to have been superseded by the newer 'flapper' type.[a]

Modification and production

From the start, the Mint found that excessive pressure had to be applied to fully bring out the design of the coin, and the dies broke rapidly. On January 10, 1922, O'Reilly, still serving as Acting Mint Director in Baker's absence, ordered production halted. Dies had been sent to the Denver and San Francisco mints in anticipation of beginning coinage there; they were ordered not to begin work until the difficulties had been resolved. The Commission of Fine Arts was asked to advise what changes might solve the problems. Both Fraser and de Francisci were called to Philadelphia, and after repeated attempts to solve the problem without reducing the relief failed, de Francisci agreed to modify his design to reduce the relief. The plaster models he prepared were reduced to coin size using the Mint's Janvier reducing lathe. However, even after 15 years of possessing the pantograph-like device, the Mint had no expert in its use on its staff, and, according to Burdette, "[h]ad a technician from Tiffany's or Medallic Art [Company] been called in, the 1922 low relief coins might have turned out noticeably better than they did".[48]

Approximately 32,400 coins on which Morgan had tried to keep a higher relief were struck in January 1922. While all were believed to have been melted, one circulated example has surfaced.[49] Also, high relief 1922 proof dollars occasionally appear on the market and it is believed that about six to 10 of them exist.[50] The new low-relief coins, which Fraser accepted on behalf of the Commission, though under protest, were given limited production runs in Philadelphia in early February. When the results proved satisfactory, San Francisco began striking its first Peace dollars using the low-relief design on February 13, with Denver initiating production on February 21, and Philadelphia on February 23.[51] The three mints together struck over 84 million pieces in 1922.[52]

The 1926 Peace dollar, from all mints, has on the obverse the word "God", slightly boldened. The Peace dollar's lettering tended to strike indistinctly, and Burdette suggests that the new chief engraver, John R. Sinnock (who succeeded Morgan after his 1925 death), may have begun work in the middle of the motto "In God We Trust", and for reasons unknown, only the one word was boldened. No Mint records discuss the matter, which was not discovered until 1999.[53]

The Peace dollar circulated mainly in the Western United States, where coins were preferred over paper money, and saw little circulation elsewhere. Aside from this use, the coins were retained in vaults as part of bank reserves. They would commonly be obtained from banks as Christmas presents, with most deposited again in January.[11] With the last of the Pittman Act silver struck into coins in 1928, the Mint ceased production of Peace dollars.[11]

Production resumed in 1934, due to another congressional act; this one requiring the Mint to purchase large quantities of domestic silver, a commodity whose price was at a historic low. This Act assured producers of a ready market for their product, with the Mint gaining a large profit in seigniorage, through monetizing cheaply purchased silver—the Mint in fact paid for some shipments of silver bullion in silver dollars.[54] Pursuant to this authorization, over seven million silver Peace dollars were struck in 1934 and 1935.[55] Mint officials gave consideration to striking 1936 silver dollars, and in fact prepared working dies, but as there was no commercial demand for them, none were actually struck.[56] With Mint Chief Engraver Sinnock thinking it unlikely that there would be future demand for the denomination, the master dies were ordered destroyed in January 1937.[57]

Striking of 1964-D dollars

On August 3, 1964, Congress passed legislation providing for the striking of 45,000,000 silver dollars. Coins, including the silver dollar, had become scarce due to hoarding as the price of silver rose past the point at which a silver dollar was worth more as bullion than as currency. The new pieces were intended to be used at Nevada casinos and elsewhere in the West where "hard money" was popular. Many in the numismatic press complained that the issue would only satisfy a small special interest, and would do nothing to alleviate the general coin shortage.[52] Much of the pressure for the coins to be struck was being applied by the Senate Majority Leader, Mike Mansfield (Democrat–Montana), who represented a state that heavily used silver dollars.[58] Preparations for the striking proceeded at a reluctant Mint Bureau. Some working dies had survived Sinnock's 1937 destruction order, but were found to be in poor condition, and Mint Assistant Engraver (later Chief Engraver) Frank Gasparro was authorized to produce new ones. Mint officials had also considered using Morgan's design; this idea was dropped and Gasparro replicated the Peace dollar dies. The reverse dies all bore Denver mintmarks; as the coins were slated for circulation in the West, it was deemed logical to strike them nearby.[59]

In early 1965, Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon wrote to President Lyndon Johnson, opposing the coin issue and pointing out that the pieces would be unlikely to circulate in Montana or anywhere else; they would simply be hoarded. Nevertheless, Dillon concluded that as Senator Mansfield insisted, the coins would have to be struck.[60] Dillon resigned on April 1; his successor, Henry H. Fowler, was immediately questioned by Mansfield about the dollars, and he assured the senator that things would be worked out to his satisfaction.[61] Mint Director Eva Adams hoped to avoid striking the silver dollars, but wanted to keep the $600,000 appropriated for that expense.[62] Senator Mansfield refused to consider any cancellation or delay and on May 12, 1965, the Denver Mint began trial strikes of the 1964-D Peace dollar[63]—the Mint had obtained congressional authorization to continue striking 1964-dated coins into 1965.[64]

The new pieces were publicly announced on May 15, 1965, and coin dealers immediately offered $7.50 each for them, ensuring that they would not circulate.[65] The public announcement prompted a storm of objections. Both the public and many congressmen saw the issue as a poor use of Mint resources at a time of severe coin shortages, which would only benefit coin dealers. On May 24, one day before a hastily called congressional hearing, Adams announced that the pieces were deemed trial strikes, never intended for circulation. The Mint later stated that 316,076 pieces had been struck; all were reported melted amid heavy security. To ensure that there would be no repetition, Congress inserted a provision in the Coinage Act of 1965 forbidding the coinage of silver dollars for five years. No 1964-D Peace dollars are known to exist in either public or private hands.[66] Two specimens were discovered in a Treasury vault in 1970 and were destroyed, but rumors and speculation about others in illegal private possession continue to appear.[67] The issue has also been privately restruck using unofficial dies and genuine, earlier-date Peace dollars resulting in an altered date.[68]

Some Peace dollars using a base metal composition were struck as experimental pieces in 1970 in anticipation of the approval of the Eisenhower dollar; they are all presumed destroyed.[69] This new dollar coin was approved by an act signed by President Richard Nixon on December 31, 1970, with the obverse to depict President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had died in March, 1969. Circulating Eisenhower dollars contained no precious metal, though some for collectors were struck in 40% silver.[70]

Mintage figures

None of the Peace dollar mintages are particularly rare, and A Guide Book of United States Coins (or Red Book) lists low-grade circulated specimens for most years for little more than the coin's bullion value. Two exceptions are the first year of issue 1921 Peace dollar, minted only at the Philadelphia mint and issued in high relief, and the low-mintage 1928-P Peace dollar. The prices for the 1928-P dollar are much lower than its mintage of 360,649 would suggest, because the U.S. mint announced that limited quantities would be produced and many were saved. In contrast the 1934-S dollar was not saved in great numbers so that prices for circulated specimens are fairly inexpensive but mid-grade uncirculated specimens can cost thousands of dollars.

| Year | Philadelphia[71] | Denver[71] | San Francisco[71] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 1,006,473 | ||

| 1922 | 51,737,000 | 15,063,000 | 17,475,000 |

| 1923 | 30,800,000 | 6,811,000 | 19,020,000 |

| 1924 | 11,811,000 | 1,728,000 | |

| 1925 | 10,198,000 | 1,610,000 | |

| 1926 | 1,939,000 | 2,348,700 | 6,980,000 |

| 1927 | 848,000 | 1,268,900 | 866,000 |

| 1928 | 360,649 | 1,632,000 | |

| 1934 | 954,057 | 1,569,500 | 1,011,000 |

| 1935 | 1,576,000 | 1,964,000 | |

| Total | 111,230,179 | 27,061,100 | 52,286,000 |

Notes and references

- ^ Vermeule 1971, pp. 150–151. Note: the source does not say that newspaper, neither does The Numismatist, Vermeule's source, see here.

- ^ Van Allen & Mallis 1991, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Van Allen & Mallis 1991, p. 30.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Van Allen & Mallis 1991, p. 31.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Van Allen & Mallis 1991, p. 409.

- ^ The Numismatist & October 1920.

- ^ a b Breen 1988, p. 459.

- ^ Burdette 2005, pp. 189–191.

- ^ a b Burdette 2008, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Breen 1988, p. 460.

- ^ a b Burdette 2005, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b Burdette 2008, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c Van Allen & Mallis 1991, p. 410.

- ^ & Stathis 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Richardson 1891, pp. 806–807, 26 Stat L. 484, amendment to R.S. §3510.

- ^ a b Burdette 2005, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Burdette 2005, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b Burdette 2005, pp. 197–198.

- ^ a b Burdette 2005, p. 198.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Taxay 1983, p. 355.

- ^ The Numismatist, de Francisci & February 1922.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Taxay 1983, p. 356.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Burdette 2005, p. 207.

- ^ a b Burdette 2005, p. 208.

- ^ Burdette 2005, p. 209.

- ^ Taxay 1983, p. 358.

- ^ Burdette 2005, pp. 208–211.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 35.

- ^ a b Burdette 2005, pp. 213–214.

- ^ The Numismatist, Zerbe & February 1922.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Burdette 2005, p. 215.

- ^ a b Van Allen & Mallis 1991, p. 411.

- ^ CoinWorld Eisenhower dollar.

- ^ CoinWorld Morgan dollar.

- ^ CoinWorld Seated Liberty dollar.

- ^ CoinWorld Trade dollar.

- ^ CoinWorld Anthony dollar.

- ^ Vermeule 1971, p. 148.

- ^ a b The New York Times & January 5, 1922.

- ^ Burdette 2005, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Burdette 2005, pp. 223–225.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 168–169.

- ^ 1922 Peace Dollar

- ^ Burdette 2005, pp. 226–227.

- ^ a b Breen 1988, p. 461.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Breen 1988, pp. 460–461.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 63.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 78–81.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 85.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 86.

- ^ The New York Times & September 13, 1964.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Burdette 2008, pp. 98–101.

- ^ 1964-D Peace Dollars - Do They Really Exist?

- ^ Moonlight Mint.

- ^ Burdette 2008, p. 102.

- ^ The New York Times & January 24, 1971.

- ^ a b c Breen 1988, pp. 461–462.

Bibliography

- Breen, Walter (1988). Walter Breen's Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins. New York, N.Y.: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-14207-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Highfill, John W. (1988–1992). The Comprehensive U. S. Silver Dollar Encyclopedia. Tulsa, OK: Highfill Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0962990007.

- Burdette, Roger W. (2008). A Guide Book of Peace Dollars. Atlanta, Ga.: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-2669-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burdette, Roger W. (2005). Renaissance of American Coinage, 1916–1921. Great Falls, Va.: Seneca Mill Press. ISBN 978-0-9768986-0-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stathis, Stephen (2009). Congressional Gold Medals, 1776–2009. Darby, Pa.: DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4379-2906-5. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taxay, Don (1983) [1966]. The U.S. Mint and Coinage (reprint ed.). New York, N.Y.: Sanford J. Durst Numismatic Publications. ISBN 978-0-915262-68-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van Allen, Leroy C.; Mallis, A. George (1991). Comprehensive Catalog and Encyclopedia of Morgan & Peace Dollars. Virginia Beach, Va.: DLRC Press. ISBN 978-1-880731-11-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Other sources

- Highfill, John W., ed. (November 12, 1982). The National Silver Dollar Roundtable NSDR. Houston, TX.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, William Allen, ed. (1891). Supplement to the revised statutes of the United States. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gilkes, Paul. "Eisenhower dollar". Coin World. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Gibbs, William T. "Morgan dollar". Coin World. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- "Fantasy over-struck coins". Moonlight Mint. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Orzano, Michele. "Seated Liberty dollar". Coin World. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- "Trade dollar". Coin World. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- Orzano, Michele. "Anthony dollar". Coin World. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- "Peace dollars popular". The New York Times. January 5, 1922. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Bardes, Herbert C. (September 13, 1964). "Treasury to go ahead on '64 date freeze". The New York Times. p. X32. Retrieved February 25, 2011. (subscription required)

- Haney, Thomas V. (January 24, 1971). "Ike dollar to be last silver coin". The New York Times. p. D29. Retrieved February 25, 2011. (subscription required)

- Zerbe, Farran (October 1920). "Commemorate peace with a coin for circulation". The Numismatist: 443–444. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- de Francisci (February 1922). "Mr. de Francisci tells of his work upon the coin". The Numismatist: 60. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Zerbe, Farran (February 1922). "Mr. Zerbe comments on the new coin". The Numismatist: 60–61. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

External links

- Peace dollar pictures

- VAMworld Morgan & Peace dollar VAMs and varieties reference site

- An Interview with Peace dollar Historian Roger Burdette