Peter O'Neill

Peter O'Neill | |

|---|---|

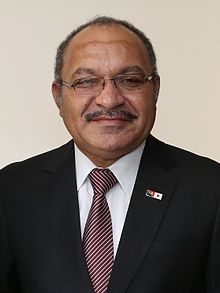

O'Neill in 2015 | |

| 8th Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea | |

| In office 2 August 2011 – 29 May 2019 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governors‑General | Sir Michael Ogio Theo Zurenuoc (Acting) Sir Robert Dadae |

| Deputy | Leo Dion Charles Abel |

| Preceded by | Sam Abal (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | James Marape |

| Minister of Finance[1] | |

| In office 27 February 2012 – August 2012 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Don Polye |

| Succeeded by | James Marape |

| In office July 2010 – July 2011 | |

| Prime Minister | Sam Abal |

| Preceded by | Patrick Pruaitch |

| Succeeded by | Don Polye |

| Member of the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea | |

| Assumed office 2002 | |

| Preceded by | Roy Yaki |

| Constituency | Ialibu-Pangia |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Peter Charles Paire O'Neill 13 February 1965 Ialibu-Pangia, Territory of Papua |

| Political party | People's National Congress |

| Spouse | Lynda May Babao |

| Alma mater | University of Papua New Guinea |

Peter Charles Paire O'Neill CMG (born 13 February 1965) is a Papua New Guinean politician who served as the seventh Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea from 2011 to 2019. He has been a Member of Parliament for Ialibu-Pangia since 2002. He was a former cabinet minister and the leader of the People's National Congress between 2006 and 2022. He resigned his position as prime minister to avoid a vote of no confidence, and he was succeeded by James Marape.

Early life

[edit]O'Neill was born on 13 February 1965 in Pangia, Territory of Papua, in the present-day Southern Highlands Province. His father, Brian O'Neill, was a magistrate of Irish Australian descent, while his mother, Awambo Yari, was of Papua New Guinean descent from the Southern Highlands. O'Neill's father moved to Papua New Guinea in 1949 as an Australian government field officer (also known as a kiap) and later served as a magistrate in Goroka until his death in 1982.

O'Neill spent the first years of his youth in his mother's village, and after attending secondary school, he stayed at his father's urban residence in Goroka. O'Neill was educated at Pangia Primary School, Ialibu High School, and Goroka High School. After leaving school, he obtained a bachelor of commerce degree from the University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG) in 1986. He later received a degree with honors in accounting from UPNG. He also obtained a professional qualification and became a Certified Practicing Accountant in 1989. A year later, he became president of the Papua New Guinea Institute of Certified Practicing Accountants. O'Neill was then a partner in Pratley and O'Neill's accounting firm. He combined this with a substantial number of directorships, often as executive chairman, including at the PNG Banking Corporation when it was government-owned.[2][3]

Early political career

[edit]O'Neill entered politics in 2002 as a Member of Parliament representing Ialibu-Pangia under Prime Minister Michael Somare. As a member of the People's National Congress (PNC), O'Neill was part of the coalition government and was appointed to the Cabinet as the Minister for Labour and Industrial Relations, then reassigned in 2003 as the Minister for Public Service. However, in 2004, he was dropped from the Cabinet, and the PNC left the coalition to join the opposition. Later that year, O'Neill became leader of the opposition, but Speaker Jeffery Nape initially did not recognise him and claimed Peter Yama held the position instead.[4][5] In response, O'Neill tried to mount a vote of no confidence without success since Somare and Nape used procedural issues to stop this.[6] After the 2007 elections, O'Neill rejoined Somare's government as the Minister of the Public Service. In July 2010, he was appointed Minister of Finance. When Somare was hospitalised in 2011, Sam Abal was appointed acting prime minister, who demoted O'Neill to Works Minister in July 2011.[7][3]

Prime minister

[edit]Cabinet O'Neill/Namah (2011-2012)

[edit]In April 2011, Somare fell ill and flew to Singapore for treatment. O'Neill then led the opposition in ousting Abal as acting prime minister. He was then elected by the Parliament as prime minister with 70 of the 94 votes cast.[8][9][10] O'Neill's claim to the position was challenged by both the East Sepik Province, where Somare was also governor, and Somare himself when he returned from Singapore. The Supreme Court ruled that Somare was the legitimate prime minister, but O'Neill retained overwhelming support in parliament. O'Neill and Somare both claimed the title of prime minister and thus arose the 2011–2012 Papua New Guinean constitutional crisis. It was resolved when the Governor General decided to call for new elections.[11][12][13]

Cabinet O'Neill/Dion (2012-2017)

[edit]In the 2012 general election, O'Neill's PNC obtained 27 seats, an increase from the 5 seats in the previous Parliament. A broad coalition appeared to support him, with 94 seats out of the 119-member Parliament.[14] This coalition contained three ex-prime ministers, among whom was Somare.

Cabinet O'Neill/Abel (2017-2019)

[edit]The PNC, which was headed by O'Neill, was the largest political party based the outcome of the 2017 elections. The election of former prime minister Mekere Morauta in the 2017 Papua New Guinean general election was a challenge,[15] but this did not endanger the position of O'Neill. His party had the most seats, and this entitled O'Neill constitutionally to form the government. However, the PNC won a mere 21 seats in the 106-seat parliament. This was substantially less than the 52 seats the PNC had occupied at the end of the previous parliament. He needed to form a coalition from a weak base in a fragmented parliament.[16][17] O'Neill succeeded again in doing that: he gained the support of 60 MPs, with 46 MPs in opposition. The majority was smaller than before, and it eroded, particularly when a debate erupted in 2018 about the benefits of natural resource projects for Papua New Guinea. Cabinets in PNG are awarded a grace period during the first 18 months in office, during which time a vote of no confidence cannot be mounted. The grace period had passed in May 2019, and the question of a no-confidence vote thereafter became pertinent.[16][17] There were several attempts before the end of the grace period to replace O'Neill as prime minister. It was suggested to him that he resign, but O'Neill did not respond.[18] However, MPs defected from the government benches as the crucial date approached. This group included prominent cabinet ministers, for example, James Marape, minister of finance, and Davis Steven, attorney general.[19]

On 7 May 2020, the rebels lodged their intention to mount a vote of no confidence with Marape as alternate PM. They claimed to have a majority behind them (57 out of a 111-member parliament).[21] O'Neill resorted, as before, to parliamentary rules to procrastinate the vote of no confidence and suggested adjourning parliament for three weeks. The opposition then mounted a motion to change the speaker of parliament, who ruled in O'Neill's favour, and this failed. Nevertheless, the vote split parliament (50–56).[22] O'Neill obtained a nine-vote majority (59–50) supporting his proposed adjournment to stave off the vote of no confidence. The opposition appeared, therefore, to be short of numbers.[23] O'Neill thereafter turned to the courts in an attempt to procrastinate with the argument that the no confidence motion could not be held as long as it was a case before the Supreme Court raising pertinent constitutional questions.[24] The political configuration changed fundamentally when William Duma and the Natural Resources Party made a deciding move and joined the opposition. This raised the number in opposition to 62, and therefore they had a definite majority in the 111-member parliament.[25]

Paradoxically, the opposition seemed then to be in disarray. First, they withdrew the vote of no confidence motion.[26] Second, they changed the leadership: Marape, the former finance minister, was the alternate PM of the opposition until 28 May. He was then replaced by Pruaitch. This was announced by Marape and reported to be by consensus.[27] However, later, it was evident that there was a vote between Marape and Pruaitch in favour of the latter.[28] O'Neill then turned again to the courts, asking for a speedy decision on his request to stay the vote of no confidence because of the urgency of a possible vote of no confidence. The Supreme Court decided on 28 May that O'Neill did not have standing because there had not been a vote of no confidence at that moment. That moment was in between the first one that was withdrawn due to a lack of numbers and the second one when the opposition had the numbers. The latter was mounted on the same day as the court's decision in favour of the opposition.[29]

A Vote of No Confidence has to pass through two hurdles to be tabled. First, the Parliamentary Business Committee had to decide whether it should be tabled in Parliament. That committee was stacked with supporters of O'Neill. The opposition won a motion to bring in supporters of their cause. The support for changes in the Parliamentary Business Committee showed that the opposition had the numbers to be a majority. The Speaker is a second hurdle to be taken. The opposition tried to change the speaker, but he successfully withstood the move.[30]

O'Neill then avoids a vote of no confidence by following the suggestion that he had rejected earlier: he resigns and appoints Julius Chan as his successor. Chan first accepted the appointment and retracted it almost immediately in an ambiguous way: he was not interested in the position but would serve the nation in a caretaker position.[31][32] There was a flurry of arguments about whether the selection of Chan was a constitutional possibility. The salient one against Chan was that the government must be formed by the leader of the largest party in parliament, which was the PNC, the party of O'Neill.[33][34]

Marape then suddenly returned to the PNC along with thirty MPs and joined the government bench. The opposition no longer had the numbers. O'Neill resigned again and handed over to Marape as prime minister, in line with the constitutional requirement that the largest party form the government. Marape engineered a comeback as a candidate MP when he was no longer the alternate PM of the opposition because he lost to Pruaitch as leader of the opposition. Marape was confirmed as prime minister with 101 votes against 8 for Morauta, the most prominent critic of O'Neill.[35][36]

Policies

[edit]O'Neill embarked on an activist development policy that he contrasted with the stagnation of previous years. He took a substantial loan from the Chinese Import-Export Bank, to remedy the "sins" of the past.[37][38] He laid stress on the development of infrastructure, especially roads.[39] Free education and free health care were signature policies in the 2012 election. He maintained these policies after being re-elected in 2017.[40][41] The international stature of PNG was raised through the organisation of the 2015 Pacific Games,[42] and the proposal of Port Moresby as the location for the APEC summit in 2020.[43]

In August 2011, the O'Neill administration announced a new public holiday, Repentance Day, on 26 August. The announcement was made eleven days before that date. The public holiday was established at the request of a "group of churches", which had approached Abal with the idea shortly before he lost his office.[44]

International relations

[edit]Australia

[edit]

Relations with Australia were on the upswing when Kevin Rudd returned to power. O'Neill and Rudd brokered the deal to locate illegal immigrants to Australia on Manus Island. This deal came to grief, however, when the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional.[45] PNG protested strongly when Australia opened a consulate in Bougainville, which could be interpreted as the recognition of Bougainville as an independent state.[46]

Indonesia

[edit]Relations with Indonesia were warm under the O'Neill government. A large trade delegation of 100 businessmen accompanied O'Neill on a state visit in 2013. It did, however, not only involve trade but also border and West Papua region issues.[47] O'Neill stuck to two elements that had been central to PNG's policy towards West Papua since independence. Indonesian sovereignty over West Papua was never in doubt, and refugees from West Papua were not recognised as such.[48] However, in 2015 he made a break with previous policies: he continued to stress the sovereignty of Indonesia, but he mentioned the human rights abuses in West Papua: "Sometimes we forget our own families, our own brothers, especially those in West Papua. I think, as a country, the time has come for us to speak about the oppression of our people there." Talking about the population of West Papua as "our people" can be interpreted as foreign intervention by Indonesia.[49] During the Melanesian Spearhead Group meeting in Port Moresby in 2018, Indonesia was given associate member status, and the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULM) was given observer status.[50] The ULM has, however, signalled its continuing interest in full membership, which O'Neill has indicated he would only support if there was full endorsement by the Indonesian government.[51][52] O'Neill suggested that ULM bring its cause to the United Nations decolonization committee.[53] This committee rebuffed, however, a petition of 1.8 million West Papuans on the grounds that West Papua was no longer a colony.[54] The Presidents of Vanuatu, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands brought the case before the UN General Assembly, but PNG did not join them.[55]

APEC and China

[edit]

Hosting the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in 2018 was a highpoint in international relations for O'Neill as prime minister. The meeting was, however, dominated by disagreement. US president Donald Trump did not come to the meeting and sent his vice president, Mike Pence. Pence did, however, stay in Cairns, Australia, and flew daily to PNG. Russia's leader, Vladimir Putin, did not attend the conference. China's highest leader, Xi Jinping, came and stayed in Port Moresby. China contributed massively to organising the meeting, especially through the building of infrastructure in Port Moresby. The capital was also decked out in Chinese flags. Chinese officials dominated the proceedings. They restricted, for example, access for the press to an important sideline meeting of China and Pacific nations. On the other hand, PNG officials reacted by taking matters into their own hands. Chinese officials were escorted out of the building by security when Rimbink Pato, the PNG minister of foreign affairs, was drafting a final communiqué with his staff.[56]

The meeting concluded without a joint communiqué because the US and China could not find common ground. That had not happened before at APEC. Australia was also wary of Chinese influence and moved rapidly before the conference to claim the harbour of Manus Island to prevent it from becoming a base for Chinese ships.[57]

The expenditure for this conference, especially the purchase of a fleet of Maserati and Bentley motorcars, played a role in the ousting of O'Neill as prime minister.[58] The conference was widely considered a failure of diplomacy.[58] O'Neill considered organising the APEC meeting a success.[59]

Governance

[edit]O'Neill was referred to as a controversial Prime Minister when he was returned in 2017.[60][61] There are laudatory comments on his tenure of office,[62][63][64] but overall it has been mired in criticism because of governance issues. These issues predate his appointment as Prime Minister. His supporters point to his success in business before entering politics as a qualification for leadership. Opponents argue that his business success is permeated with influence in government and that his directorships in government enterprises prior to his success in politics are significant.[65]

National Provident Fund

[edit]The commission of inquiry in the National Provident Fund of 2003 recommended prosecuting O'Neill for extorting money in return for revaluing a contract to build a high-rise. A rise in the contract price was given because of rising costs as a consequence of currency devaluation, and O'Neill was said to obtain a cut from this increase. O'Neill appeared in a committal court in 2005, but the charges were dropped due to insufficient evidence.[66] O'Neill had no objection to reopening the case.[67]

Paraka legal fees

[edit]O'Neill's name was involved in an enquiry into the irregular disbursement of massive legal fees to the law firm of Paul Paraka. Paraka was arrested in December 2013 because of fraudulent payments totaling up to 30 million Australian dollars.[67] Opposition leader Belden Namah mentioned O'Neill as responsible because he was Minister of Finance at the time of the payment.[68] Another irregular payment of 31 million Australian dollars occurred after the government apparently cut ties with Paraka lawyers when O'Neill was Prime Minister.[69] There were attempts by the Investigation Task Force Sweep, an anti-corruption watchdog, and police officers from the Anti-Corruption Unit to question O'Neill. He refused to be questioned and dismissed the Task Force Sweep and the police officers involved.[70] O'Neill challenged an arrest warrant against him before the courts, and the Supreme Court voided the warrant in December 2017 as defective. This was on formal grounds, as officers did not follow the regulations, information was missing, and there were spelling mistakes.[71][72]

OK Tedi and PNGSDP

[edit]O'Neill nationalised the Ok Tedi Mine owned by the PNG Sustainable Development Fund (PNGSDF) without compensation. The O'Neill government had stated after taking power in 2012 that it intended to obtain a bigger share of dividends from the mine, but nationalisation without compensation came as a surprise.[73][74][75] He mentioned environmental damage as the main reason. BHP Biliton was the owner of the mine when it was opened, but they wanted to close the mine as a consequence of major environmental damage due to negligence. The Government was faced with a great loss of revenue, and a formula was found to continue mining. BHP transferred its shares to a trust fund for the local community, and in return, BHP was granted immunity from claims because of environmental damages while BHP continued to manage the mine. O'Neill considered that a mistake and revoked the immunity. One concern was that proceeds from the mine were disappearing abroad instead of staying within PNG. This is connected to a political rivalry with former Prime Minister Morauta, whose political base is in that part of the country. Morauta, as chairman of the PNGSDF, challenged the nationalisation without compensation and refused access to the externalised PNGSDF in Singapore, which is meant as a Social Wealth Fund for when the mine is exhausted. The case is continuing in the Singaporean courts. The government has gained the right to inspect the books of PNGSDP as it is a shareholder, but the issue of ownership is still undecided.[76] An arbitration attempt in Singapore failed as there was no written consent to arbitration from the PNG government.[77] Morauta brought a case before the courts in PNG as well. However, the Supreme Court decided that Morauta had no standing as a private person to bring the case, and the court was also not admissible as the case was before a court in a foreign jurisdiction.[78] However, Morauta won in Singapore. It was a disappointment for O'Neill that the Singaporean High Court decided against his claim on PNGSDP. He immediately announced an appeal and a Commission of Enquiry.[79] Controversies surround the unwinding of the PNGSDF's affairs within PNG under the control of the government. PNGSDF owned the Cloudy Bay timber company. This involved extensive logging rights. This company has been sold far below its value to investors who are not above suspicion.[80] Greg Sheppard, a lawyer close to O'Neill, has been charged with defrauding a trust fund established to aid communities impacted by the OkTedi mine. These charges also imply money laundering. Sheppard denies this and considers the case politically motivated.[81] However, the public prosecutor has followed up on the case with more charges.[82]

UBS/Oil Search

[edit]He also faced an alleged disregard for regulatory control and political procedure in arranging a loan from the Swiss banking firm UBS to obtain shares in Oil Search. The intention of this loan was to become a shareholder in the group developing the Elk Antelope Oil Field. O'Neill ignored such procedures in obtaining this loan.[83] Don Polye, his Minister for Treasury, refused to sign. O'Neill then appointed himself Minister for Treasury. These issues led to an investigation by the Ombudsman Commission, which recommended bringing O'Neill before a leadership tribunal. O'Neill welcomed the chance to clear his name. However, he delayed the appointment of a new Chief Ombudsman and appointed a controversial Acting Chief Ombudsman.[84] O'Neill's lawyers challenged the powers of the Ombudsman to investigate the Prime Minister as well as publish and distribute the resulting information. The Ombudsman should first inform the Prime Minister in such cases. The Supreme Court ruled that the Ombudsman Commission was under no obligation to inform the Prime Minister in such instances.[85] The report that O'Neill wanted to suppress came out in May 2019. It did not only indicate O'Neill but, among others, also his successor, Marape. He was Minister of Finance when the deal was concluded.[86] Prior to this information from the Ombudsman, there was news that Swiss financial regulators would look into the matter.[87] Prime Minister Marape has installed a Commission of inquiry under the leadership of the chief justice and with the head of the anti-corruption Task force, Sweep, as council. Its brief is limited to the legality of the events, and it has to report within three months.[88] The commission of inquiry materialised somewhat later, in March 2021. O'Neill testified without any reservations. He welcomed the enquiry and considers it essential that the truth be told: "The enquiry is necessary." O'Neill was unapologetic; members of his former cabinet who deny knowledge of how the loan came to be approved were cowards.[89][90] He declared himself happy with the loan.[91]

The opposition to O'Neill on these issues was intense. University students went on strike demanding his resignation, which resulted in violent confrontations with the police and the closure of the University of Papua New Guinea for the academic year.[92] Three former Prime Ministers, Somare, Chan, and Morauta, supported a motion of no confidence and urged O'Neill to resign.[93]

When O'Neill resigned, he was therefore under siege from several sides; it was not only his parliamentary majority that was at stake. He was also under threat from the Ombudsman Commission, and a Leadership Tribunal may have resulted from the report.[94] Despite these issues, there was also praise for O'Neill after his resignation. Instead of facing a vote of no confidence, he was praised by Marape.[95] William Duma, who had made a definite move against his premiership, praised him as well.[96]

Economy

[edit]O'Neill presided over a period of economic growth attributable in the main to the commencement of the ExxonMobil-Total PNG LNG project, construction of which began in 2010 and production of LNG in 2014. 2014 was also the peak for economic growth in PNG, with GDP growth of around 15.4%.[97] Optimism regarding future revenues was buoyant and resulted in a significant carry-forward in government spending, which included scheduled wage increases for public servants and the construction of vanity infrastructure, including Oilsearch Stadium and APEC Haus.[98] The buoyancy was short-lived; by 2018, an earthquake coupled with declining economic activity saw GDP growth fall to 0.8%.[97] Wage increases were postponed and became future-year liabilities that the budget could not afford.[99] Faced with declining revenues, falling business confidence, and poor prospects for recovery, a challenge to his leadership became inevitable.

O'Neill systematically defended his whole performance in an interview after he lost office. That is most notable and controversial with respect to the UBS loan meant to acquire interests in the Elk Antelope gas field through a shareholding in Oil Search. He claims that investigations by regulatory authorities in Switzerland and Australia declared everything in order. "They've found that these arrangements were in order, except that nobody predicted the collapse of the world prices... I mean, nobody could predict it. So we were caught in a situation where we needed to sell down these shares". Oil Search is, according to him, a great asset for PNG and deserves to be supported.[59] He sees his policies for free education and health care as a success. He does not deny that there are problems in the delivery of these services, e.g., shortages of medicines or late payment of teacher salaries, but according to him "It is more of a management problem than the government not prioritising",[59] His successor, Marape, described the economy when presenting his first budget as "struggling and bleeding", and also said that the country was in "a very deep economic hole".[100] O'Neill, in response, claimed that the budget was based on false information published for political gain. According to O'Neill, the treasurer had created a higher debt-to-GDP ratio simply by changing the methodologies used to inflate the number. He considers the negative view of the PNG economy to be IMF-inspired, and the budget is made up by foreign academics who had not even lived in the country.[101]

O'Neill and Marape

[edit]It seemed that O'Neill would retain power after his resignation. He was the leader in parliament of the largest political party, the PNC. However, he seemed soon to be an isolated dissenter. At the end of August 2019, it came to an outburst: he protested strongly against the appointment of Ian Ling-Stuckey as Minister of the Treasury, who opposed O'Neill as Shadow Treasury Minister. O'Neill objected not only to this appointment but condemned in general the appointment of MPS, who had opposed the O'Neill-Abel cabinet. O'Neill predicted that "it will not be long before Morauta and Opposition Leader Patrick Pruaitch join government so be prepared to make way for them."[102] This came true in November, when Marape made another government reshuffle, removing members of the O'Neill/Able cabinet. He appointed Pruaitch as Minister of Foreign Affairs.[103] Morauta said he would not be interested in a Cabinet position but that he was willing to support the Cabinet as "deckhand" to Captain Marape.[104] Marape told O'Neill in August to leave the government benches and go into opposition. Marape declared himself no longer a member of the PNC but of the Pangu Party. He declared himself elected by people from all parties in parliament and was therefore not answerable to the PNC. Marape was supported by the Speaker, Job Pomat, who nevertheless declared himself a member of the PNC. O'Neill had therefore no longer a hold on his party. There were mass defections from the PNC, leading to the Pangu Party being the largest in Parliament. Due to that, Marape therefore claimed the right to form the government as proscribed in the constitution.[105][103] On matters of policy, he condemned the repudiation of the agreement with the Energy companies about the Elk Antelope gas field. Second, he accuses the Marape government of giving a false negative picture of the economy inspired by outsiders, including the Australian economist Paul Flanagan and the IMF.[106]

Opposition

[edit]O'Neill continued to come under fire after his move to the cross-bench and subsequently in opposition. Accusations of impropriety were led by Member for Madang and Minister for Police Bryan Kramer, MP. Kramer had, as a former member of the Opposition while O'Neill was Prime Minister, accused O'Neill of holding dual (PNG and Australian) citizenship, which would disqualify him from Parliament. O'Neill maintained that this was false and challenged Kramer to provide evidence.[107]

In October 2019, an arrest warrant was served on O'Neill on the basis of official corruption.[108] O'Neill was released on bail and travelled to Australis in November 2019 for an extended period of time.[109] He was arrested shortly after returning on 23 May 2020, again on charges of official corruption, stemming from the purchase of two generators from a company in Israel with which he was accused of having close ties. O'Neill said the allegations were politically motivated and that he had not personally benefited from the procurement of the generators.[110] The accusation was originally based on misappropriation and official corruption;[111] however, it was turned into a more formal charge of following procedures instead of an outright criminal charge.[112] The National Court dismissed the charge.[113] O'Neill considered the case an attempt to block him in the next general election and stated defiantly, "You have to defeat me at the elections".[114] Prime Minister Marape was Minister of Finance at the time of the purchase and stated in court that the generators were not suitable for PNG and were gathering dust.[115] In reply to a question by the MP Gary Juffa in 2019, it was stated that the diesel generators were too expensive to run for PNG power and that only one was serviceable.[116]

Vote of no confidence in Marape government

[edit]He seemed to become more and more of an isolated politician, but that appeared not to be true in the attempt to mount a vote of no confidence in the Marape government at the end of 2020. O'Neill was among several ex prime ministers and deputy prime ministers in the group asking for a vote of no confidence.[117] O'Neill was a vocal leader among them. He accused the Marape government of irresponsible management of the economy and especially mismanagement of the resources sector: "Over 80 percent of our economy depends on the resource sector, when you mismanage that the economy obviously suffers," and "No-one in their right mind shuts down an operating gold mine (Porgera) when the prices are at the top of its peak".[118] O'Neill and Namah initiated the move towards a vote of no confidence, but they played no role in the vote for an alternate prime minister. Both had to face court cases, and this influenced their positions. They were not contenders in the final vote that elected Pruaitch as the alternate prime minister.[119] The vote of no confidence foundered because the opposition appeared to be too fragmented in its choice of alternate prime minister to muster a majority. They split between supporters of Pruaitch and Sam Basil. The latter rejoined the government.[120] Pruaitch rejoined the government in May 2021 and was no longer the alternative prime minister of the opposition.[121] Namah welcomed the move but insisted on continuing with the court cases resulting from the attempted Vote of No Confidence and declared to name a new alternative prime minister to renew the attempt: The dire state of the economy demanded this.[122] The name proposed as an alternative Prime Minister was O'Neill. The court cases of Namah as well as of O'Neill had been cleared, and therefore the way was open.[123] The combination of Namah and O'Neill is remarkable, as they had been on very bad terms when O'Neill ignored his former deputy Prime Minister after the 2012 election.[124] O'Neill won re-election to the National Parliament in 2022 in the first round with a large majority, which is unusual in the country.[125] No one voted for him in the subsequent election for Prime Minister, and he declared himself no longer a contender for the post.[126]

Personal life

[edit]O'Neill has been married to Lynda May Babao since 1999. They have five children: Brian, Travis, Joanne, Loris, and Patrick. It is his second marriage. He was appointed to the Order of St Michael and St George as a Companion in the 2007 Birthday Honours List.[127]

References

[edit]- ^ "Hon. Peter Charles Paire O'Neill, CMG, MP - Tenth Parliament of Papua New Guinea". www.parliament.gov.pg.

- ^ "Hon. Peter Charles Paire O'Neill, CMG, MP - Tenth Parliament of Papua New Guinea". www.parliament.gov.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b Callick, Rowan. Highlander with big shoes to fill Available at: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/inquirer/highlander-with-big-shoes-to-fill/news-story/2ca803e861b240017f20c4e652dda990 Posted on: 16 September 2011

- ^ "PNG government dismisses opposition enthusiasm for no-confidence vote". RNZ. 1 July 2004. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG Opposition leader not recognised in Parliament". ABC News. 27 May 2004. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ R.J. May and Ray Anere (2011), Background to the 2007 election: recent political developments in R.J. May et al. Election 2007: The shift to Limited Preferential Voting in Papua New Guinea Canberra: ANU: State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Program and Boroko (PNG): National Research Institute pp. 13–14

- ^ Yehiura Nriehwazi http://www.pireport.org/articles/2011/07/07/abalâ%C2%80%C2%99s-tenure-acting-prime-minister-question Posted on: 7 July 2011 Accessed on: 22 February 2017

- ^ Callick, Rowan (3 August 2011). "PNG vote weakens link to Michael Somare era". The Australian. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Nicholas, Isaac (3 August 2011). "O'Neill is PM". The National. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Bill Standish, PNG's new prime minister: Peter O'Neil http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2011/08/11/pngs-new-prime-minister-peter-o-neill/

- ^ Gridneff, Ilya (16 December 2011). "'Coup' ends PNG political crisis". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea in crisis as two claim to be prime minister". The Guardian. 14 December 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea political crisis ends as Governor-General changes mind". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea's democracy at work". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 August 2012.

- ^ Namorong, Martyn (14 February 2017). "Sir Mekere announces intention to contest 2017 elections". Namorong Report. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b Nalu, Malum (16 November 2016). "PNC party leads with 52 MPs". The National. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ a b Sean Dorney, PNG election surprises Posted on: 11 August 2017 Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/papua-new-guinea-election-surprises Accessed on: 22 December 2018

- ^ R.J. May, Politics in Papua New Guinea 2017–20: From O'Neill to Marape Discussion paper: Department of Pacific affairs. p.5 Available at: http://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2020-11/dpa_dp_may_20203.pdf Accessed on: 9/1/2021

- ^ "Five PNG ministers have now quit as O'Neill government hit by crisis | Asia Pacific Report". Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ For a clear overview of the succession struggle: Michael Kabuni, PNG's fluid politics: winners and losers from O'Neill to Marape, Available at:https://devpolicy.org/pngs-fluid-politics-winners-and-losers-from-oneill-to-marape-20190619/ The legal situation regarding the vote of no confidence is clearly explained by: Michael Kabuni Three issues that will shape png politics from 2020-222 Available at:https://devpolicy.org/three-issues-that-will-shape-png-politics-from-2020-to-2022-20200220/ Posted on: 20/2/2020 Accessed on: 9/1/2021

- ^ "PNG Politics : Opposition joins Marape Camp, 57 in Camp". Papua New Guinea Today (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG's Prime Minister Delays No-Confidence Vote by Adjourning Parliament". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG Opposition declares "the game is on" as PM thwarts plans to oust him". ABC News. 8 May 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Pokiton, Sally. "State files VoNC stay motion". Loop PNG. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "PNG Politics: Duma joins Opposition, 62 MPs in Camp". Papua New Guinea Today (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG opposition withdraws vote of no confidence against O'Neill | Asia Pacific Report". Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Pruaitch is alternate PM". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "CAN YOU TRUST A LIAR, BETRAYER AND HYPOCRITE?". 20 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "PNG Politics : Prime Minister Peter O'Neill's case on VoNC adjourned". Papua New Guinea Today (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Chaos in Parliament – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ PM O'Neill Steps Down, Julius Chan is Acting Prime Minister Available at: https://Posted on 26/5/2019 www.pngfacts.com/news/pm-oneill-steps-down-julius-chan-is-acting-prime-minister Accessed 4/1/2021

- ^ "Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O'Neill resigns". BBC News. 26 May 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG PM O'Neill's resignation unconstitutional , says Sir Amet". Papua New Guinea Today (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Kabuni, Michael (2 June 2020). "PNG's unanswered constitutional questions pile up". Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea MPs elect James Marape to be next prime minister". The Guardian. 30 May 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "James Marape elected as PNG's new PM". SBS News. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PM Peter O'Neill says loans are necessarily to remove "sins" of the past government". One Papua New Guinea. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ http://www.news.com.au/world/breaking-news/png-to-borrow-big-from-china/news-story/5728f723e7ff0338707311ca2a577628 Posted on 26 September 2012

- ^ http://www.pm.gov.pg/pm-oneill-road-infrastructure-is-key-to-economic-development/ Posted by PM_Admin on 7 June 2017

- ^ "Election Focus: Peter O'Neill's Key Policies". The Garamut. 4 June 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "O'Neill confident govt will expand on policies". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Port Moresby puts on a show at opening of 2015 Pacific Games". ABC News. 4 July 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Freddy Mau: O'Neill officially invites leaders to summit Posted on 11/11/2017/ at http://www.looppng.com/png-news/o'neill-officially-invites-leaders-summit-69418 Accessed 15 March 2018

- ^ "Day of Repentance puzzles Papua New Guinea". www.abc.net.au. 26 August 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Kama, Bal (27 April 2016). "PNG Supreme Court ruling on Manus Island detention centre". Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Snow, Deborah (15 May 2015). "Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O'Neill unhappy at Australian move over Bougainville". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Trade, extradition and West Papua on agenda for PNG-Indonesia talks". ABC News. 13 June 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Sean Dorney (1990), Papua New Guinea, People, Politics and History since 1975, Milsons Point: Random House Australia; Chapter 9: Irian Jaya

- ^ "PNG prime minister raises human rights in West Papua". country.eiu.com. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Indonesia, West Papua invited to MSG meet – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ PNG pemier Peter ONeill backs Widodos bid to join Melanesian group Available at: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/world/png-pm-peter-oneill-backs-widodos-bid-to-join-melanesian-group/news-story/20f35767dbaebb2a4812e4b67764a67f Posted on: 13 May 2015

- ^ "West Papua movement confident of PNG support for membership bid". RNZ. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ PNG pm urges Pacific countries to take Papua issue to the UN Available at: https://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific- news/361534/png-pm-urges-pacific-countries-to-take-papua-issue-to-un Posted on: 10 July 2018 Accessed on: 14 January 2019

- ^ "West Papua independence petition is rebuffed at UN". The Guardian. 30 September 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Pacific leaders call out Indonesia at UN over West Papua". RNZ. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "APEC summit in PNG dominated by US China jousting". RNZ. 19 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "In APEC host Papua New Guinea, China and the West grapple over strategic port". Reuters. 14 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Maseratigate: Opposition at loggerheads with govt". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Manus, Maseratis and corruption: Peter O'Neill on eight years leading Papua New Guinea". The Guardian. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG's PM Peter O'Neill to serve another term after troubled elections". ABC News. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ R.J. May Papua New Guinea under the O'Neill government: Has there been a change in political style? ANU: SSGM Discussion paper 2017/6 Available at: http://ssgm.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2017-08/dp_2017_6_may.pdf Accessed on: 25 April 2018

- ^ "Peter O'Neill, best performing Prime Minister in PNG' history". Papua New Guinea Today (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Gentle man, Peter O'Neill, the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea". PNG Echo. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Anabel, Sir Peter Ipatas: I am supporting O'Neill because he is a good prime minister https://pngdailynews.com/2017/08/01/sir-peter-ipatas-i-am-supporting-oneill-because-he-is-a-good-prime-minister/ Posted on: 1 August 2017

- ^ "The Midas Touch: How Peter O'Neill and his associates have made a killing – Part 1". PNGi Central. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Cedric Patjole Former NPF contributions unrecoverable. Available at: http://www.looppng.com/business/former-npf-contributions-unrecoverable-54220 Accessed on: 12 April 2018

- ^ a b "PNG lawyer charged over $30m in fraudulent payments". ABC News. 24 October 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG opposition leader cleared of fraud". The Age. 12 January 2006. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Second letter undermines PNG leader's forgery claims: MP". ABC News. 9 July 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Peter O'Neill sacks top PNG policeman and shuts down corruption watchdog". The Guardian. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Arrest warrant for PNG prime minister Peter O'Neill thrown out of court". The Guardian. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ 'Parakagate and its ongoing fallout' in R.J. May Papua New guinea under the O'Neill government: Has there been a change in political style? ANU: SSGM Discussion paper 2017/6 Available at http://ssgm.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2017-08/dp_2017_6_may.pdfAccessed on: 25 April 2018

- ^ "Complex challenges for PM O'Neill in mining". Papua New Guinea Mine Watch. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG govt passes laws to take over former BHP Ok Tedi mine". ABC News. 18 September 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Howes, Stephen (23 September 2013). "The remarkable story of the nationalization of PNG's largest mine and its second largest development partner, all in one day". Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Independent State of Papua New Guinea v PNG Sustainable Development Program Ltd [2016] SGHC 19 Originating Summons No 234 of 2015 Date of judgement: 12 February 2016 Judge: Judith Prakash Available at: http://www.singaporelaw.sg/sglaw/laws-of-singapore/case-law/free-law/high-court-judgments/18364-independent-state-of-papua-new-guinea-v-png-sustainable-development-program-ltd Retrieved 10 November 2017

- ^ "Unanimous ICSID tribunal dismisses expropriation claim due to Papua New Guinea's lack of written consent to arbitrate – Investment Treaty News". Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Sally Pokiton, Sir Mekere has no standing in PNGSDP, says court. Published on Loop PNG 19 October 2016 Available at: http://www.looppng.com/content/sir-mekere-has-no-standing-pngsdp-case-says-court Retrieved 10 November 2017

- ^ "PNG: Govt loses legal battle to control billion-dollar Sustainable Development Program". ABC Pacific. 8 April 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "'Too good to be true': the deal with an Isis-linked Australian family that betrayed PNG's most marginalised". The Guardian. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Australian Greg Sheppard's law firm says charges over PNG mine fund are "politically motivated"". The Guardian. 22 January 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Sheppard's Second Arrest June 12, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2023.

- ^ Yala, Charles (21 March 2014). "The Oil Search loan: implications for PNG". Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ R.J. May Papua New Guinea under the O'Neill government: Has there been a change in political style? ANU: SSGM Discussion paper 2017/6 Available at: http://ssgm.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2017-08/dp_2017_6_may.pdf Accessed on: 25 April 2018 pp.12–13

- ^ NG Supreme Court Rules Ombudsman Not Obliged To Inform PM of Investigations From: PNG Post/Courier Posted on: 30 March 2017 Available at: http://www.pireport.org/articles/2017/03/30/png-supreme-court-rules-ombudsman-not-obliged-inform-pm-investigations Accessed on: 23 April 2018

- ^ "PNG PM O'Neil misled NEC on USB Loan deals : Leaked OC Report". Papua New Guinea Today (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Swiss regulator probes UBS Australia's $1.2b PNG loan". Australian Financial Review. 14 March 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Sir Salamo sets tentative date for UBS Commission of Inquiry to begin". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Ministers were aware of UBS loan, says O'Neill". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "O'Neill fronts UBS inquiry - happy with controversial loan". RNZ. 21 June 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG's O'Neill labels former colleagues cowardly at inquiry". RNZ. 11 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "University of Papua New Guinea cancels academic year after student unrest". The Guardian. 7 July 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea prime minister Peter O'Neill must resign, say former leaders". The Guardian. 20 July 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "O'Neill outmanoeuvres PNG opposition with formal resignation". Australian Financial Review. 29 May 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Marape pays tribute to former PM". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Duma heaps praise on PM O'Neill". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Papua New Guinea – Slower Growth, Better Prospects". Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "Australia bankrolls PNG summit costs". ABC News. 31 January 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea's salary bill problem". 14 September 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "PNG turns to Australia for help out of its "deep economic hole" - ABC Radio". AM - ABC Radio. 9 October 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Budget data false, says O'Neill – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Ling-Stuckey appointment an insult to govt MPs: O'Neill". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Marape v O'Neill – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Sir Mek teams up with govt". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG's PM assumes leadership of Pangu Pati". RNZ. 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Bernard Yegiora PNGs confusing budget debate available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/pngs-confusing-budget-debate Posted on 10 October 2019

- ^ "PNG PM Peter O'Neill in dual citizenship crisis mode". ABC News. 21 May 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "O'Neill faces arrest". Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "Former PNG PM O'Neill denies fleeing country". Radio New Zealand. 4 November 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea police arrest former PM Peter O'Neill over alleged corruption". TheGuardian.com. 23 May 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Former PNG PM O'Neill to stand trial over Israeli generators purchase Available at; :https://asiapacificreport.nz/2020/12/02/former-png-pm-oneill-to-stand-trial-over-israeli-generators-purchase/ Posted on: 2/12/2020 Accessed: 4/1/2022

- ^ 'Neill questioned over generator purchase: Police Available at: https://www.looppng.com/png-news/o'neill-questioned-over-purchase-generators-police-92340 Posted on: 23/5/2020 Accessed: 4/1/2022

- ^ Court acquits O'Neill Available at https://postcourier.com.pg/court-acquits-oneill/ Posted:15/10/21 Accessed on: 4/1/2022

- ^ "Not guilty – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "PNG Power not able to use gensets, says Marape – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "MP: Generators expensive to maintain – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "List of Parties and MPs as of 16th November 2020". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Natalie Whiting and Michael Walsh, Papua New Guinea's political crisis is heading to the courts. Here's what you need to know Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-21/papua-new-guinea-political-crisis-what-you-need-to-know/12899078 Posted on 21/11/21 Accessed on: 2/2/2021

- ^ "Pruaitch chosen as alternative PM". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Frenemies forever? PNG's prime minister sees off a challenge". www.lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Pruaitch back with Govt – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Namah: Vote-of-no-confidence motion still pursued – The National". www.thenational.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Peter O'Neill new alternate PM". postcourier.com.pg. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Rowan Callick, PNG leaders Peter O'Neill and Belden Namah accuse each other Available at: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/world/png-leaders-peter-oneill-and-belden-namah-accuse-each-other/news-story/c08cf468884d3ee630bbcd277bd4c7ae Posted on: 19/11/2019 Accessed: 24/01/2022

- ^ "Massive election victory for O'Neill". www.pngreport.com. 24 July 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ editor, A. P. R. (4 August 2022). "O'Neill 'bombshell' throws top position in PNG elections wide open | Asia Pacific Report". Retrieved 8 July 2024.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Page 35 | Supplement 58362, 16 June 2007 | London Gazette | The Gazette". www.thegazette.co.uk.

External links

[edit]- People's National Congress Party, PNG-Integrity of Political Parties & Candidates Commission

- The Australian: Highlander with big shoes to fill

- 1965 births

- Living people

- Prime ministers of Papua New Guinea

- Ministers of finance of Papua New Guinea

- 2011–2012 Papua New Guinean constitutional crisis

- Members of the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea

- Government ministers of Papua New Guinea

- Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Papua New Guinean accountants

- Papua New Guinean businesspeople

- Papua New Guinean people of Australian descent

- Papua New Guinean people of Irish descent

- People from the Southern Highlands Province

- People's National Congress (Papua New Guinea) politicians

- University of Papua New Guinea alumni

- Heads of government who were later imprisoned

- 21st-century Papua New Guinean politicians

- Leaders of the Opposition (Papua New Guinea)