Pina Menichelli

Pina Menichelli | |

|---|---|

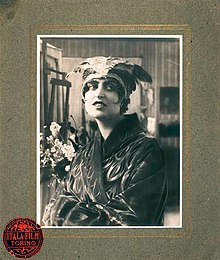

Pina Menichelli in The Fire (1916) | |

| Born | Giuseppa Iolanda Menichelli 10 January 1890 Castroreale, Italy |

| Died | 29 August 1984 (aged 94) Milan, Italy |

| Occupation | Actress in Italian silent films |

| Years active | 1912–1924 |

| Partner(s) | Libero Pica (1908–1924) Baron Carlo Amato (1924–?) |

Giuseppa Iolanda Menichelli (10 January 1890 – 29 August 1984), known as Pina Menichelli, was an Italian actress and silent film star. After a career in theatre and a series of small film roles, Menichelli was launched as a film star when Giovanni Pastrone gave her the lead role in The Fire (1916). Over the next nine years, Menichelli made a series of films, often trading on her image as a diva and on her passionate, decadent eroticism. Menichelli became a global star, and one of the most appreciated actresses in Italian cinema, before her retirement in 1924, aged 34.

Since her death, restorations of Menichelli's surviving films have been shown at important film festivals, and her filmography has been re-assembled and re-evaluated by film historians.

Biography

Early life

Giuseppa Iolanda Menichelli was born on 10 January 1890 in Castroreale, a small village in the province of Messina, Sicily. Her parents, Cesare and Francesca Malvica, were both touring theatre actors, who performed in Sicilian language.[1] The Menichellis were part of a dynasty of performers, which included Nicola Menichelli, an important eighteenth century comedian.[2] Her older sister Lilla, younger sister Dora and brother Alfredo all became actors.[1] Pina Menichelli was educated at the Sacre Cuore Catholic School in Bologna.[1]

Being part of a family of touring actors, Menichelli started acting as child.[1] Her first important role was in 1907 in a theatre company run by Irma Gramatica and Flavio Andò, which toured Argentina in 1908.[1] Menichelli married and took up residence in Buenos Aires in 1909.[1]

Start of film career

After her return to Italy in 1912, Menichelli acted in around thirty-five films made by Cines of Rome in 1913–1915.[3] Menichelli initially had parts in action-adventure films (Le mani ignote, Zuma and Il banchiere), before gaining supporting roles in several films based around famous actresses, such as Hesperia (Olga Mambelli), Soava Gallone and Gianna Terribili-Gonzales.[4] Menichelli received positive reviews for her performances in In Contrasto (1913), Il siero del dottor Kean (1913) and La barca nuziale (1913).[5] Menichelli played Cleopatra in Cajus Julius Caesar (1914), but all her scenes were cut from the final film.[6]

In the Napoleonic war epic Scuola d'eroi (1914), Menichelli had a cameo as a drummer girl.[7] Legend has it that her performance struck Giovanni Pastrone, the director of Cabiria, who cut a frame from the film reel and ordered that the unknown actress be brought to Itala Films of Turin.[8] However, reviews of her last films at Cines suggest that Menichelli was well on her way to film stardom before her move to Itala Films. Menichelli had graduated to starring roles in feature films, and her performances were generally positively reviewed, earning her favourable comparisons with Lyda Borelli and Francesca Bertini, the two most famous Italian film actresses of the time.[9] One reviewer noted Menichelli's, "uncommon talent," in Alla Deriva (1915).[9] Commenting on La casa di nessuno (1915), another reviewer remarked, "The public like Menichelli, and that's enough. I could say that I like her too."[9]

Screen breakthrough: Il Fuoco and Tigre Reale

In 1915, Giovanni Pastrone decided to launch Menichelli as a film star, and gave her the lead role in Il Fuoco (The Fire), which was a global popular and critical success.[10] This acclaim catapulted Menichelli into the ranks of the lavishly-paid cinema divas, such as Francesca Bertini and Lyda Borelli.[10] The film bore no formal relation to Gabriele d'Annunzio's novel of the same name, and was developed from a screenplay by Febo Mari, Menichelli's co-star. However, the film was full of d'Annunzian themes of violent passion, power and decadence.[11] The film is divided into three parts: La Favilla (the spark), La Vampa (the flame/blaze) and Il Cenere (the ashes), which correspond with the three phases of the relationship between Menichelli's aristocratic poet and Mari's impoverished painter. The original poster for Il Fuoco depicts a key moment in the film. Menichelli's character knocks over an oil lamp, and asks Mari's character to choose between love and all-consuming passion, and he chooses the latter.[12] Menichelli's feathered hat, long capes and fierece gestures make her seem like an owl and reinforce one of the film's motifs; the link between the femme fatale and birds of prey.[10] Menichelli earned the nickname 'Our Lady of Spasms' for her abrupt gestures in this film.[10]

In 1916, Menichelli's status as a screen diva was cemented by Tigre Reale (Royal Tiger), directed by Giovanni Pastrone. The screenplay was loosely adapted from a novel by Giovanni Verga,[12] who refused to have his name appear on the poster or in the film's credits.[13] The plot concerns a diplomat, La Ferlita (Alberto Nepoti), who falls in love with the Russian Countess Natka (Menichelli). Natka frequently encourages then rejects La Ferlita, and their love story is broken up by a long flashback to Natka's previous relationship with a young revolutionary called Dolski (Febo Mari).[14] Amid some beautiful snow scenes, Countess Natka's chance encounter with Dolski leads to a passionate romance. Exiled to Siberia, Dolski betrays Natka and kills himself when Natka finds him.[14] After telling La Ferlita the story, Natka then disappears for several months, and La Ferlita is unable to find her. When the countess and the diplomat eventually meet, they are locked in a room in a huge theatre and hotel, which goes up in flames.[15] The impressive scenes of the fire were made with the help of expert cinematographer Segundo de Chomon.[15] The film's structure demonstrates Pastrone's secure grasp of cinematic form.[12] Pastrone made excellent use of extended flashbacks and highlighted the parallels in the narrative with an effective system of montage.[12] Tigre Reale was a huge commercial success.[10]

In Il Fuoco and Tigre Reale, Menichelli impressed cinema audiences with her, "...erotic charge, seductive glances and provocative body movements," and established herself as the femme fatale of Italian silent cinema.[16] Both Il Fuoco and Tigre Reale are perfect examples of what Aldo Bernardini defined as, "tailcoat cinema."[13] Both films allowed audiences a passport into the exciting lives of the upper-classes; an imaginary world of luxury where it was possible to transgress Italian society's strict moral codes.[13] [17] More widely, both films have also been mentioned as classics of the diva genre, although Menichelli's acting style was very different from the more theatrical styles of Francesca Bertini and Lyda Borelli. While Bertini rejected close-ups in the early part of her career, Menichelli managed to express a lot of emotion in them. [16] Unlike Bertini, Menichelli did not claim to be the 'creator' of her character, and worked under the orders of her directors.[16]

Career at Itala Films

Only a brief fragment of Gemma di Sant'Eremo (1916) has survived, making any judgement of the film or Menichelli's performance difficult.[18] The film was a success in Spain, France and Central America.[19]In Italy, the film's ending was changed on the orders of the Italian censors, and the film was a commercial failure.[19] A similar fate also awaited L'Olocausto, which had been made by Itala in 1915, and was only released in Italy in 1919, having been cut from 1400 to 955m.[20] The film was a commercial failure in Italy.[20] However L'Olocausto was released uncensored in Britain, France and Germany, and was a commercial success.[20]

In 1918, La moglie di Claudio (Claudio's wife) was banned from cinemas by the Italian censorship board because Menichelli was "troppo...affascinante!" (too...fascinating!) in the film.[16] Una Sventella (1918) was released to moderate reviews.[21] In 1919, Menichelli starred in Il padrone delle ferriere (The boss of the ironworks) alongside Amleto Novelli, one of the most famous Italian actors of the period.[22] The film was a huge commercial and critical success.[22]

Move to Rinascimento Film

In 1919, Menichelli broke down in tears when she asked Giovanni Pastrone for his permission to leave Itala Films.[23] During her four years at Itala Films, Menichelli's career had reached great heights, and her salary had increased from 12,000 lira per year to 300,000 lira per year.[23] Menichelli moved to Rinascimento Film of Rome, which had been founded specifically for her by Baron Carlo D'Amato, and made a total of thirteen films there between 1919 and 1923.[24] Despite the deepening crisis in the Italian film industry during these years,[25] Menichelli's films continued to do well commercially because of her enduring popularity in certain countries, such as Mexico,[26] and Rinascimento Film's calculated appeal to export markets, which included adapting foreign texts and putting foreign co-stars alongside Menichelli.

In 1920, Menichelli starred in La Storia di Una Donna (The Story of a Woman), her first production at Rinascimento Film. Highly unusually for the time, the story of the protagonist is told through an extended flashback.[27] An unconscious woman with gunshot wounds is brought into the city hospital. After conversing with her doctor, a detective finds the woman's diary, which is then used to tell the story of her life. At the end of the film, the unknown woman dies, having never regained consciousness, and the detective sets off to arrest her killer.[27] The sets and interiors, extravagant in Menichelli's earlier films, were reduced to a bare minimum, and the film used low-key lighting in a similar way to the German Expressionists, creating large areas of shadow within the set.[27]

In 1922, Rinascimento Film decided to adapt a play by English author Arthur Wing Piñero called The Second Wife. Menichelli travelled to London to shoot the exterior scenes. The resulting film, La Seconda Moglie (1922), was praised by English and Italian critics alike.[28]

In 1923, the final year of her career, Menichelli starred in two light-hearted romantic comedies, La Dama di chez Maxim and Occupati D'Aemilia. Her co-star in both films was French actor Marcel Lévesque, best known for his comic roles in Louis Feuillade's serial films Les Vampires (1915) and Judex (1917).[29] This marked a change from her usual serious roles, and both films were very popular with the public.[29]

Retirement

Menichelli retired from the silent screen in 1924.[10]

Personal Life and Family

During a theatrical tour of Argentina in 1909, Pina Menichelli married an Italo-Argentine, Libero Pica, and the couple had three children.[30] One child, a boy, was born in 1909 and died shortly afterwards.[30] The second, a son called Manolo, was born in 1910.[30] The couple separated when Menichelli was pregnant with their third child, a daughter called Cesarina, who was born in Milan in 1912.[30]

The fact that Menichelli was a 'separated woman' was well-known to the Italian public.[31] This contrasts with the likes of Emilio Ghione, one of the most famous Italian male film stars of the 1910s, who managed to hide his separated wife from public view.[32]

On the death of her first husband, who had always refused to annul their marriage, Menichelli married Baron Carlo D'Amato, founder of Rinascimento Film, in 1924.[33] Menichelli retired from public life and refused all contact with film historians.[34] Menichelli also destroyed all the documents and photographs relating to her film career which were in her possession.[35]

Menichelli died in Milan on 29 August 1984.[35]

Filmography

- Le mani ignote, directed by Enrique Santos (1913)

- Zuma, directed by Baldassarre Negroni (1913)

- Il lettino vuoto, directed by Enrico Guazzoni (1913)

- Il romanzo, directed by Nino Martoglio (1913)

- La porta chiusa, directed by Baldassarre Negroni (1913)

- Retaggio d’odio, directed by Nino Oxilia (1914)

- Scuola d’eroi, directed by Enrico Guazzoni (1914)

- La parola che uccide, directed by Augusto Genina (1914)

- Il grido dell’innocenza, directed by Augusto Genina (1914)

- Giovinezza trionfa!, regia di Augusto Genina (1914)

- Lulù, directed by Augusto Genina (1914)

- I misteri del castello di Monroe, directed by Augusto Genina (1914)

- Ninna nanna, directed by Guglielmo Zorzi (1914)

- Julius Caesar, directed by Enrico Guazzoni (1914)

- La morta del lago, directed by Enrico Guazzoni (1915)

- Alla deriva, directed by Enrico Guazzoni (1915)

- Il sottomarino n. 27, directed by Nino Oxilia (1915)

- Alma mater, directed by Enrico Guazzoni (1915)

- Papà, directed by Nino Oxilia (1915)

- La casa di nessuno, directed by Enrico Guazzoni (1915)

- The Fire, directed by Giovanni Pastrone (1915)

- Tigre reale, directed by Giovanni Pastrone (1916)

- La trilogia di Dorina, directed by Gero Zambuto (1916)

- Gemma di Sant'Eremo, directed by Alfredo Robert (1916)

- Una sventatella, directed by Gero Zambuto (1916)

- La passeggera, directed by Gero Zambuto (1918)

- La moglie di Claudio, directed by Gero Zambuto (1918)

- L'olocausto, directed by Gero Zambuto (1918)-known as Golden Plait in Britain.

- Il giardino incantato, directed by Eugenio Perego (1918)

- The Railway Owner, directed by Eugenio Perego (1919)

- Noris, directed by Augusto Genina and Eugenio Perego (1919)

- A Woman's Story, directed by Eugenio Perego (1920)

- La disfatta dell’Erinni, directed by Eugenio Perego (1920)

- The Story of a Poor Young Man, directed by Amleto Palermi (1920)

- La verità nuda, directed by Telemaco Ruggeri (1921)

- Le tre illusioni, directed by Eugenio Perego (1921)

- L'età critica, directed by Amleto Palermi (1921)

- The Second Wife, directed by Amleto Palermi (1922)

- L'ospite sconosciuta, directed by Telemaco Ruggeri (1923)

- La donna e l'uomo, directed by Amleto Palermi (1923)

- La dama de Chez Maxim's, directed by Amleto Palermi (1923)

- Una pagina d’amore, directed by Telemaco Ruggeri (1923)

- La biondina, directed by Amleto Palermi (1923)

- Take Care of Amelia, directed by Telemaco Ruggeri (1925)

Surviving Film Copies

Like many silent films, many of Menichelli's films have been lost because nitrate film was dangerous to store, and films were often projected until they were no longer watchable, then simply recycled. Restorations of Menichelli's films have been shown at important film festivals, including the New York Film Festival and the Pordenone Silent Film Festival.[36][37]

The following films are preserved in film archives:

- Una tragedia al cinematografo (1913) is preserved at the EYE Film Institute in the Netherlands.[38]

- Zuma (1913) is preserved at the Cineteca Nazionale, Rome, Italy.[38]

- The fire (Il fuoco) (1916) is preserved in the archives of the Italian National Cinema Museum, Turin, Italy.[39]

- Tigre reale (1916), is preserved in the archives of the Italian National Cinema Museum, Turin, Italy, and in the archives of the Cineteca Nazionale, Rome, Italy.[40]

- Gemma di Sant'Eremo (1916), is preserved in the archives of the Cineteca Nazionale, Rome, Italy.[38] Only a fragment of the film survives.[18]

- Il padrone delle ferriere (1919) is preserved in the archives of the Italian National Cinema Museum, Turin, Italy.[41]

- La storia di una donna (1920), is preserved at the Cineteca of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.[42]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Martinelli 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Bosco 1968, p. 367.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, pp. 67–75.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, p. 70–71.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, p. 72–73.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Martinelli 2002, pp. 81–83.

- ^ a b c d e f Blom 2005, p. 428.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d Brunetta 2008, pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b c Abrate & Longo 1997, p. 79.

- ^ a b Usai 1986, p. 92.

- ^ a b Usai 1986, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d Brunetta 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Brunetta 2008, p. 124.

- ^ a b Redi 1999, p. 104.

- ^ a b Martinelli 2002, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b c Martinelli 2002, pp. 102–3.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, pp. 101.

- ^ a b Martinelli 2002, pp. 107–109.

- ^ a b Usai & 1986 (ed.), p. 69.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, p. 32.

- ^ Redi 1999, pp. 175–183.

- ^ Jandelli 2007, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Brunetta 2008, p. 276.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, pp. 32 & 21.

- ^ a b Martinelli 2002, pp. 33 & 129.

- ^ a b c d Martinelli 2002, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Jandelli 2007, p. 45.

- ^ Lotti 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, p. 34.

- ^ Martinelli 2002, Introduction.

- ^ a b Martinelli 2002, p. 19.

- ^ "the 38th new york film festival". passion and defiance: silent divas of the italian cinema. the new york film festival. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Il restauro di Il fuoco alle Giornate del Cinema Muto di Pordenone 2010". News. Italian National Cinema Museusm (MNC). Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Redi 1999, pp. 224–228.

- ^ "Il Fuoco". Restored silent films. Italian National Cinema Museusm (MNC). Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Redi 1999, p. 227.

- ^ "Il padrone delle ferriere". Restored silent films. Italian National Cinema Museusm (MNC). Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "Film: Storia di una donna, la". Bibliomedioteca catalogue. Cineteca of Bologna. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

Bibliography

This article lacks ISBNs for the books listed. (April 2011) |

- Abrate, Piero; Longo, Germano (1997). Cento anni di cinema in Piemonte. Turin: Abacus Edizioni.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Alacci (Alacevich), Tito (1919). Le noste attrici cinematografiche. Florence: Bemporad & Figli.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blom, Ivo (2005). "Menichelli Pina". In Abel, Richard (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Early Film. London: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brunetta, Gian Piero (2008). Storia Del Cinema Muto Italiano. Bari: Laterza.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bosco, U (1968). Lessico universale italiano. Vol. 13. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jandelli, Cristina (2007). Breve Storia Del Divismo cinematografico. Venice: Marsilio.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lotti, Denis (2008). Emilio Ghione, l'ultimo apache. Bologna: Edizioni Cineteca di Bologna.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martinelli, Vittorio (2002). Pina Menichelli. Le sfumature del fascino. Rome: Bulzoni.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Palmieri, Eugenio Ferdinando (1994). Vecchio Cinema Italiano. Vicenza: Neri Pozza Editore. ISBN 88-7305-458-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Redi, Riccardo (1999). Cinema Muto Italiano (1896-1930). Rome/Venice: Bianco & Nero, Marsilio.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Usai, Paolo Cherchi (1986). Giovanni Pastrone. Florence: Il Castoro/La Nuova Italia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Usai, Paolo Cherchi, ed. (1986). Giovanni Pastrone. Gli anni d'oro del cinema a Torino. Turin: Strenna UTET.