Pitcher

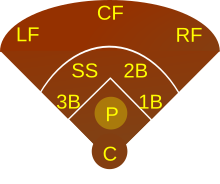

In baseball, the pitcher is the player who throws the baseball from the pitcher's mound toward the catcher to begin each play, with the goal of retiring a batter, who attempts to either make contact with the pitched ball or draw a walk. In the numbering system used to record defensive plays, the pitcher is assigned the number 1. The pitcher is often considered the most important defensive player, and as such is situated at the right end of the defensive spectrum.

Traditionally, the pitcher also bats. Starting in 1973 with the American League and spreading to further leagues throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the hitting duties of the pitcher have generally been given over to the position of designated hitter, a cause of some controversy. The National League in Major League Baseball and the Japanese Central League are among the remaining leagues that have not adopted the designated hitter position.

Overview

In most cases, the objective of the pitcher is to deliver the pitch to the catcher without allowing the batter to hit the ball with the bat. A successful pitch is delivered in such a way that the batter either allows the pitch to pass through the strike zone, swings the bat at the ball and misses it, or hits the ball poorly (resulting in a pop fly or ground out). If the batter elects not to swing at the pitch, it is called a strike if any part of the ball passes through the strike zone and a ball when no part of the ball passes through the strike zone. A check swing is when the batter begins to swing, but then stops the swing short. If the batter successfully checks the swing and the pitch is out of the strike zone, it is called a ball.

There are two legal pitching positions, the windup and the set position or stretch. Either position may be used at any time; typically, the windup is used when the bases are empty, while the set position is used when at least one runner is on base. Each position has certain procedures that must be followed. A balk can be called on a pitcher from either position. A power pitcher is one who relies on the velocity of his pitches to succeed.[1] Generally, power pitchers record a high percentage of strikeouts. A control pitcher succeeds by throwing accurate pitches and thus records few walks.

Nearly all action during a game is centered around the pitcher for the defensive team. A pitcher's particular style, time taken between pitches, and skill heavily influence the dynamics of the game and can often determine the victor. Starting with the pivot foot on the pitcher's rubber at the center of the pitcher's mound, which is 60 feet 6 inches (18.44 m) from home plate, the pitcher throws the baseball to the catcher, who is positioned behind home plate and catches the ball. Meanwhile, a batter stands in the batter's box at one side of the plate, and attempts to bat the ball safely into fair play.

The type and sequence of pitches chosen depend upon the particular situation in a game. Because pitchers and catchers must coordinate each pitch, a system of hand signals is used by the catcher to communicate choices to the pitcher, who either vetoes or accepts by shaking his head or nodding. The relationship between pitcher and catcher is so important that some teams select the starting catcher for a particular game based on the starting pitcher. Together, the pitcher and catcher are known as the battery.

Although the object and mechanics of pitching remain the same, pitchers may be classified according to their roles and effectiveness. The starting pitcher begins the game, and he may be followed by various relief pitchers, such as the long reliever, the left-handed specialist, the middle reliever, the setup man, and/or the closer.

In Major League Baseball, every team uses Baseball Rubbing Mud to rub game balls in before their pitchers use them in games.[2]

Pitching in a game

|

|

A skilled pitcher often throws a variety of different pitches to prevent the batter from hitting the ball well. The most basic pitch is a fastball, where the pitcher throws the ball as hard as he can. Some pitchers are able to throw a fastball at a speed of over 100 miles per hour (161 km/h) (such as Aroldis Chapman). Other common types of pitches are the curveball, slider, changeup, cutter, sinker, screwball, forkball, split-fingered fastball, slurve, and knuckleball. These generally are intended to have unusual movement or to deceive the batter as to the rotation or velocity of the ball, making it more difficult to hit. Very few pitchers throw all of these pitches, but most use a subset or blend of the basic types. Some pitchers also release pitches from different arm angles, making it harder for the batter to pick up the flight of the ball. (See List of baseball pitches.) A pitcher who is throwing well on a particular day is said to have brought his "good stuff".

There are a number of distinct throwing styles used by pitchers. The most common style is a three-quarters delivery in which the pitcher's arm snaps downward with the release of the ball. Some pitchers use a sidearm delivery in which the arm arcs laterally to the torso. Some pitchers use a submarine style in which the pitcher's body tilts sharply downward on delivery, creating an exaggerated sidearm motion in which the pitcher's knuckles come very close to the mound.

Effective pitching is vitally important in baseball. In baseball statistics, for each game, one pitcher will be credited with winning the game, and one pitcher will be charged with losing it. This is not necessarily the starting pitchers for each team, however, as a reliever can get a win and the starter would then get a no-decision.

Rotation and specialization

Pitching is physically demanding, especially if the pitcher is throwing with maximum effort. A full game usually involves 120–170 pitches thrown by each team, and most pitchers begin to tire before they reach this point. As a result, the pitcher who starts a game often will not be the one who finishes it, and he may not be recovered enough to pitch again for a few days. The act of throwing a baseball at high speed is very unnatural to the body and somewhat damaging to human muscles; thus pitchers are very susceptible to injuries, soreness, and general pain.

Teams have devised two strategies to address this problem: rotation and specialization. To accommodate playing nearly every day, a team will include a group of pitchers who start games and rotate between them, allowing each pitcher to rest for a few days between starts. A team's roster of starting pitchers are usually not even in terms of skill. Exceptional pitchers are highly sought after and in the professional ranks draw large salaries, thus teams can seldom stock each slot in the rotation with top-quality pitchers.

The best starter in the team's rotation is called the ace. He is usually followed in the rotation by 3 or 4 other starters before he would be due to pitch again. Barring injury or exceptional circumstances, the ace is usually the pitcher that starts on Opening Day. Aces are also preferred to start crucial games late in the season and in the playoffs; sometimes they are asked to pitch on shorter rest if the team feels he would be more effective than the 4th or 5th starter. Typically, the further down in the rotation a starting pitcher is, the weaker he is compared with the others on the staff. The "5th starter" is seen as the cut-off between the starting staff and the bullpen. A team may have a designated 5th starter, sometimes known as a spot starter or that role may shift cycle to cycle between members of the bullpen or Triple-A starters. Differences in rotation setup could also have tactical considerations as well, such as alternating right- or left-handed pitchers, in order to throw off the other team's hitting game-to-game in a series.

Teams have additional pitchers reserved to replace that game's starting pitcher if he tires or proves ineffective. These players are called relief pitchers, relievers, or collectively the bullpen. Once a starter begins to tire or is starting to give up hits and runs a call is made to the bullpen to have a reliever start to warm up. This involves the reliever starting to throw practice balls to a coach in the bullpen so as to be ready to come in and pitch whenever the manager wishes to pull the current pitcher. Having a reliever warm up does not always mean he will be used; the current pitcher may regain his composure and retire the side, or the manager may choose to go with another reliever if strategy dictates. Commonly, pitching changes will occur as a result of a pinch hitter being used in the late innings of a game, especially if the pitcher is in the batting lineup due to not having the designated hitter. A reliever would then come out of the bullpen to pitch the next inning.

When making a pitching change a manager will come out to the mound. He will then call in a pitcher by the tap of the arm which the next pitcher throws with. The manager or pitching coach may also come out to discuss strategy with the pitcher, but on his second trip to the mound with the same pitcher in the same inning, the pitcher has to come out. The relief pitchers often have even more specialized roles, and the particular reliever used depends on the situation. Many teams designate one pitcher as the closer, a relief pitcher specifically reserved to pitch the final inning or innings of a game when his team has a narrow lead, in order to preserve the victory. Other relief roles include set-up men, middle relievers, left-handed specialists, and long relievers. Generally, relievers pitch fewer innings and throw fewer pitches than starters, but they can usually pitch more frequently without the need for several days of rest between appearances. Relief pitchers are typically guys with "special stuff". Meaning that they have really effective pitches or a very different style of delivery. This makes the batter see a very different way of pitching in attempt to get them out. One example is a sidearm or submarine pitcher.

After the ball is pitched

The pitcher's duty does not cease after he pitches the ball. Unlike the other fielders, a pitcher and catcher must start every play in a designated area. The pitcher must be on the pitcher’s mound, with one foot in contact with the pitcher’s rubber, and the catcher must be behind home plate in the catcher’s box. Once the ball is in play, however, the pitcher and catcher, like the other fielders, can respond to any part of the field necessary to make or assist in a defensive play.[3] At that point, the pitcher has several standard roles. The pitcher must attempt to field any balls coming up the middle, and in fact a Gold Glove Award is reserved for the pitcher with the best fielding ability. He must head over to first base, to be available to cover it, on balls hit to the right side, since the first baseman might be fielding them. On passed balls and wild pitches, he covers home-plate when there are runners on. Also, he generally backs up throws to home plate. When there is a throw from the outfield to third base, he has to back up the play to third base as well.

Pitching biomechanics

The physical act of overhand pitching is complex and unnatural to the human anatomy. Most major league pitchers throw at speeds between 60 and 100 mph, putting high amounts of stress on the pitching arm. Pitchers are by far the most frequently injured players and many professional pitchers will have multiple surgeries to repair damage in the elbow and shoulder by the end of their careers.

As such, the biomechanics of pitching are closely studied and taught by coaches at all levels and are an important field in sports medicine. Glenn Fleisig, a biomechanist who specializes in the analysis of baseball movements, says that pitching is "the most violent human motion ever measured."[4] He claims that the pelvis can rotate at 515–667°/sec, the trunk can rotate at 1,068–1,224°/s, the elbow can reach a maximal angular velocity of 2,200–2,700°/s and the force pulling the pitcher's throwing arm away from the shoulder at ball release is approximately 280 pounds-force (1,200 N).[4]

The overhead throwing motion can be divided into phases which include windup, early cocking, late cocking, early acceleration, late acceleration, deceleration, and follow-through.[5] Training for pitchers often includes targeting one or several of these phases. Biomechanical evaluations are sometimes done on individual pitchers to help determine points of inefficiency.[6] Mechanical measurements that are assessed include, but are not limited to, foot position at stride foot contact (SFC), elbow flexion during arm cocking and acceleration phases, maximal external rotation during arm cocking, horizontal abduction at SFC, arm abduction, lead knee position during arm cocking, trunk tilt, peak angular velocity of throwing arm and angle of wrist.[7][8][9]

Some players begin intense mechanical training at a young age, a practice that has been criticized by many coaches and doctors, with some citing an increase in Tommy John surgeries in recent years.[10] Fleisig lists nine recommendations for preventative care of children's arms.[11] 1) Watch and respond to signs of fatigue. 2) Youth pitchers should not pitch competitively in more than 8 months in any 12-month period. 3) Follow limits for pitch counts and days or rest. 4) Youth pitchers should avoid pitching on multiple teams with overlapping seasons. 5) Youth pitchers should learn good throwing mechanics as soon as possible: basic throwing, fastball pitching and change-up pitching. 6) Avoid using radar guns. 7) A pitcher should not also be a catcher for his/her team. The pitcher catcher combination results in many throws and may increase the risk of injury. 8) If a pitcher complains of pain in his/her elbow, get an evaluation from a sports medicine physician. 9) Inspire youth to have fun playing baseball and other sports. Participation and enjoyment of various activities will increase the youth's athleticism and interest in sports.[11]

To counteract shoulder and elbow injury, coaches and trainers have begun utilizing "jobe" exercises, named for Dr. Frank Jobe, the pioneer of the Tommy John procedure.[12] Jobes are exercises that have been developed to isolate, strengthen and stabilize the rotator cuff muscles. Jobes can be done using either resistance bands or lightweight dumbbells. Common jobe exercises include shoulder external rotation, shoulder flexion, horizontal abduction, prone abduction and scaption (at 45°, 90° and inverse 45°).

In addition to the Jobes exercises, many pitching coaches are creating lifting routines that are specialized for pitchers. Pitchers should avoid exercises that deal with a barbell. The emphasis on the workout should be on the legs and the core. Other body parts should be worked on but using lighter weights. Over lifting muscles, especially while throwing usually ends up in a strain muscle or possible a tear.

Equipment

Other than the catcher, pitchers and other fielders wear very few pieces of equipment. In general the ball cap, baseball glove and cleats are equipment used. Currently there is a new trend of introducing a pitcher helmet to provide head protection from batters hitting line drives back to the pitcher. As of January 2014, MLB approved a protective pitchers cap which can be worn by any pitcher if they choose.[13] San Diego Padres relief pitcher, Alex Torres was the first player in MLB to wear the protective cap.[14]

One style of helmet is worn on top of the ballcap to provide protection to the forehead and sides.[15]

As for softball, a full face helmet is available to all players including pitchers.[16] These fielder's masks are becoming increasingly popular in younger fast pitch leagues, some leagues even requiring them.

See also

- Pitching machine

- List of baseball pitches

- Baseball fielding positions

- Cy Young Award winners

- List of Major League Baseball pitchers with 200 career wins

- Bowler – similar position in cricket

- American Sports Medicine Institute – Pitching Biomechanics Evaluation

References

- ^ "Velocity". Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. 2007. Retrieved August 10, 2007.

- ^ Schneider, Jason (July 4, 2006). "All-American mud needed to take shine off baseballs". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ Baseball Explained, by Phillip Mahony. McFarland Books, 2014. See www.baseballexplained.com

- ^ a b Dean, J. (October 2010). "Perfect Pitch". WIRED. 18 (10): 62.

- ^ Benjamin, Holly J.; Briner, William W., Jr. (2005), "Little League Elbow", Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 15 (1): 37–40, doi:10.1097/00042752-200501000-00008

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Archived 2008-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Whiteley, R. (2007). "Baseball throwing mechanics as they relate to pathology and performance – A review". Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 6 (1): 1–20.

- ^ Barrentine, S. W.; Matsuo, T.; Escamilla, R. F.; Fleisig, G. S.; Andrews, J. R. (1998). "Kinematic Analysis of the Wrist and Forearm during Baseball Pitching". Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 14 (1): 24–39.

- ^ Matsuo, T., Matsumoto, T., & Takada, Y. (1999). Influence of different shoulder abduction angles during baseball pitching on throwing performance and joint kinetics. p.389-392.. (). Australia:

- ^ http://fullcountpitch.com/2009/02/06/pitching-perspectives-with-rick-peterson-understanding-the-epidemic-of-youth-pitching-injuries/

- ^ a b Fleisig, G. S.; Weber, A.; Hassell, N.; Andrews, J. R. (2009). "Prevention of elbow injuries in youth baseball pitchers". Current Sports Medicine Reports. 8 (5): 250–254. doi:10.1249/jsr.0b013e3181b7ee5f.

- ^ Jeran, J. J.; Chetlin, R. D. (2005). "Training the shoulder complex in baseball pitchers: A sport-specific approach". Strength & Conditioning Journal. 27 (4). Allen Press: 14–31. doi:10.1519/1533-4295(2005)27[14:ttscib]2.0.co;2.

- ^ {http://espn.go.com/espn/otl/story/_/id/10363291/pitchers-protective-caps-approved-major-league-baseballhttp:// | Pitchers protective cap approved, January 28, 2014}

- ^ {http://www.pitchershelmet.com/who-was-the-first-pitcher-to-wear-protective-headgear/ | Who was the first pitcher to wear protective headgear, July 1, 2014}

- ^ "New Pitching Helmet Prototype Unveiled by Easton-Bell Sports". Reuters. March 7, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ "Softball Helmet: Selection and prices for the popular models". Fastpitch-softball-coaching.com. March 21, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

Further reading

- Ballard, Chris; Good, Owen (October 17, 2011). "The Invisible Fastball: Six decades ago a minor league pitcher accomplished something we'll never see again". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

When [Kelly] Jack Swift arrived in Elkin, N.C., in late 1951, he was nobody's idea of a prospect.