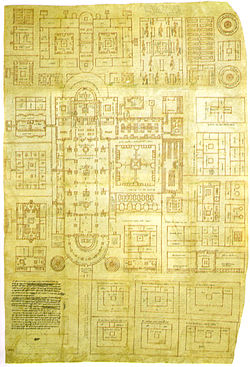

Plan of Saint Gall

The Plan of Saint Gall is a famous medieval architectural drawing of a monastic compound dating from the early 9th century. It is preserved in the Stiftsbibliothek Sankt Gallen, Ms 1092. It is the only surviving major architectural drawing from the roughly 700-year period between the fall of the Roman Empire and the 13th century. It is considered a national treasure of Switzerland and remains an object of intense interest among modern scholars, architects, artists and draftsmen for its uniqueness, its beauty, and the insights it provides into medieval culture.

Overview

The Plan depicts an entire Benedictine monastic compound including churches, houses, stables, kitchens, workshops, brewery, infirmary, and even a special house for bloodletting. The Plan was never actually built, and was so named because it was kept at the famous medieval monastery library of the Abbey of St. Gall, where it remains to this day. It was drawn in a scriptorium in Reichenau in the third decade of the 9th century, dedicated to Abbot Gozbert (816-836) of Saint Gall.

The Plan was created from five parchments sewn together measuring 45 inches by 31 inches (113 cm by 78 cm) and drawn in red ink lines for the buildings, and brown ink for lettered inscriptions. It is drawn to an "unusual" scale of 1:192 (although as explained in detail in the "The Plan of St. Gall in brief" by Lorna Price, this is 1/16" to the foot, which would not be so surprising as necessary to place the overall plan onto this size piece of parchment). The reverse of the Plan was inscribed in the 12th century, after it had been folded into book form, with the Life of Saint Martin by Sulpicius Severus. About 350 partly rhyming appendices in the handwritings of two different scribes describe the functions of the buildings. The dedication to Abbot Gozbert is written in the margin.

Because the plan does not correspond to any place that was actually built[1], just about every aspect of the Plan is disputed by modern scholars. Debates continue on things such as which system of measurement was used; whether the scale is a single scale for the entire plan or varied for different elements; if the plan is a copy from a lost prototype or the original; if it is reflective of a single individual's ideas, or those of monastic council.

Despite the unknowns, much has been learned about medieval life from the Plan. The absence of heating in the dining hall, for instance, may not have been an oversight but was meant to discourage excessive enjoyment of meals. In the quarters for the 120-150 monks, their guests, and visitors, the ratio of toilet seats was better than what modern hygienic codes would prescribe.

The Dedication

The plan was dedicated to Gozbertus, the Abbot of St Gall from 816-36. The text reads [as translated by Horn into English]

For thee, my sweetest son Gozbertus, have I drawn this briefly annotated copy of the layout of the monastic buildings, with which you may exercise your ingenuity and recognize my devotion, whereby I trust you do not find me slow to satisfy your wishes. Do not imagine that I have undertaken this task supposing you to stand in need of our instruction, but rather believe that out of love of God and in the friendly zeal of brotherhood I have depicted this for you alone to scrutinise. Farewell in Christ, always mindful of us, Amen.[2]

The Latin reads:

Haec tibi dulcissime fili cozb(er)te de posicione officinarum paucis examplata direxi, quibus sollertiam exerceas tuam, meamq(ue) devotione(m) utcumq(ue) cognoscas, qua tuae bonae voluntari satisfacere me segnem non inveniri confido. Ne suspiceris autem me haic ideo elaborasse, quod vos putemus n(ost)ris indigere magisteriis, sed potius ob amore(m) dei tibi soli p(er) scrutinanda pinxisse amicabili fr(ater)nitatis intuitu crede. Vale in Chr(ist)o semp(er) memor n(ost)ri ame(n).[3]

Derivative works

Horn and Born

Walter Horn and Ernest Born in 1979 published a 3-volume The Plan of St. Gall (Berkeley, Calif., University of California Press), which is widely considered to be the definitive work.

According to Horn, the Plan was a copy of an original blueprint of an ideal monastery created at two Carolingian reform synods held at Aachen in 816 and 817. The purpose of the synods was to establish Benedictine monasteries throughout the Carolingian Empire as a bulwark against encroaching Christian monastic missionaries from Britain and Ireland who were bringing Celtic lifestyle influences to the Continent (see Celtic art).

Umberto Eco

According to Earl Anderson (Cleveland State University), it is likely that Umberto Eco mentions the Plan in The Name of the Rose [1]:

- "perhaps larger but less well proportioned" (p. 26): Adso (a character in the book) mentions actual monasteries that he had seen in Switzerland and France (St. Gall, Cluny, Fontenay), but the standard of "proportion" most likely alludes to the Carolingian (9th century) "Plan of St. Gall," which sets forth an architectural plan for an ideal monastery.

Models

The Plan has a tradition of model making. In 1965 Ernest Born and others created a scale model of the Plan for the Age of Charlemagne exhibition in Aachen, Germany. This became the inspiration for the 1979 book, but was also the first in a tradition of modeling the plan. More recently the Plan has been modeled on computers using CAD software.

References

- ^ The abbey church of the medieval period has been excavated in 1964-66, but its form does not reflect that on the plan. Excavations were reported in Horn, The Plan of St. Gall, vol. 2, pp. 256-359.

- ^ Horn, Plan of St. Gall, vol. 3, p. 16.

- ^ Charles McClendon, The Origins of Medieval Architecture (London, 2005), p. 232, n. 51.

- The St. Gall Plan Monastery: 3D models and high-resolution images of the actual plan.

- Components list. List of individual buildings with zoomed pictures.

- CAD files. CAD files of the Plan.

- "St Gall: The Tradition and Topicality of its Cultural Memory" by Werner Wunderlich (University of St Gall). See 5th paragraph, Library chapter, for discussion of the Plan.

- Edward A. Segal (1989). "Monastery and Plan of St. Gall". Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Volume 10. ISBN 0-684-18276-9

- "The Plan of St. Gall" by Karlfried Froehlich. Book review of the Horn and Born book, background information of the plan.

- Walter Horn and Ernest Born (1979). The Plan of St. Gall (Berkeley, Calif., University of California Press, 1979).