Plaza de Armas (Cusco)

| Plaza Mayor del Cusco | |

|---|---|

| Haukaypata or Huacaypata | |

National Cultural Heritage and World Heritage Site | |

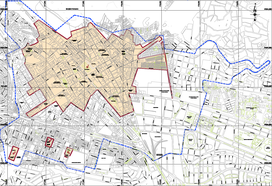

Location map | |

| Type | Public square |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 13°31′00″S 71°58′44″W / 13.516711°S 71.978822°W |

| Area | 28728 square meters |

| Created | 11th century |

| Founder | Legendary establishment of the city by Manco Capac |

| Status | Open |

| Other information | Adjacent roads, from the Cathedral in a clockwise direction:

Calle Triunfo Calle Santa Catalina Angosta Calle Loreto Calle Mantas Calle del Medio Calle Espaderos Calle Plateros Calle Procuradores Calle Suecia Calle Cuesta del Almirante |

Plaza Mayor del Cusco at present time | |

| |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Type | Main Square |

| |

The Plaza de Armas of Cusco is located in the city of Cusco, Peru. Located in the historic center of the city is the main public space of the town since before its Spanish foundation in 1534.

Geological studies carried out in the area show that it originally had a swamp,[1] crossed by the Saphy River (currently channeled and covered). During the Inca Empire, this swamp was dried up and transformed into the administrative, religious and cultural center of the imperial capital.[2] It was the place where all kinds of ceremonies were held and the victories of the Inca army were celebrated. After the Spanish conquest, it was transformed into a plaza (square) by the new rulers, who built Catholic temples and mansions on the ruins of the ancient Inca palaces. In this square, Túpac Amaru II was executed in 1781 as well as the cacique Bernardo Tambohuacso, Mateo Pumacahua and several other heroes of the independence of Peru.

Today it is the central core of modern Cusco, surrounded by tourist restaurants, jewelry stores, travel agencies and the same Catholic churches built during the colonial period and which constitute two of the most important monuments of the city: the Cathedral of Cusco and the Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús (Church of the Society of Jesus).

Since 1972, the building has been part of the Monumental Zone of Cusco, declared a Historic Monument of Peru.[3] Likewise, in 1983, as part of the historic center of the city of Cusco, it became part of the central zone declared by UNESCO as a World Cultural Heritage Site.[4]

Controversy over the original name

[edit]There is still no agreement on the proper name in Quechua that the current Plaza de Armas bore during the time of the Incas. According to some authors, such as María Rostworowski, who follows Gonzales Holguín's theory, the name was called Aucaypata (Awqay(?) Pata (in Quechua: place of the warrior)).[5] Others like Angles Vargas say it was Huacaypata (Waqay Pata, (in Quechua: place of weeping)).[6] According to him, the name contrasts perfectly with the name of the other sector of the Plaza Kusipata which means: Plaza del Regocijo (Rejoicing Square). Others like the North American traveler George Squier (whose expedition to Cusco was in 1863) assure that its name was Huacapata (in Quechua: sacred place).[7]

Victor Angles explains that the Plaza was formed by two sectors: Huacaypata and Cusipata (everyone agrees on the name of the latter) separated by the Saphy River and both would have a symbolic meaning because while the first one means place of crying the second one means place of rejoicing.[6] According to the author this would be due to the meditation ceremonies of the Inca nobles in the square which ended in crying.[6] These ceremonies were forbidden by an archbishop and were replaced by "the three-hour sermon" of the Cusco Cathedral, which also usually ended in tears. Currently the population of Cusco in general agrees that its ancient name was Huacaypata.

History

[edit]Swamp

[edit]When Manco Cápac arrived in the valley of Cusco, he settled in the surroundings of a swamp located between two streams (Saphy and Tullumayo) because that place was free from the threats of neighboring ethnic groups.[1] The swamp was formed due to the continuous irrigation of the Saphy and Tullumayu rivers. Manco Capac built his palace called Colcampata at the base of the Sacsayhuaman plateau and the city was always built around the swamp.[8] Sinchi Roca, son and successor of Manco Capac dried the swamp with earth brought from the mountains[1] and later Pachacuti was in charge of drying it completely covering the swamp with sand brought from the coast.[9]

Inca Empire

[edit]During the Inca period, the main square was larger than the current square because in addition to the current square (former Huacaypata) it occupied the entire area of the current Plaza Regocijo (formerly Cusipata), the "Hotel Cusco" and the blocks located between Calle Espaderos, Calle del Medio and Calle Mantas.[10] Precisely these blocks and the Calle del Medio were crossed by the Saphy River (currently covered and made sewer), which divided the square into its two sectors already known.[11] It was the religious and administrative center of the Inca Empire. As well as being the main axis of the Inca road.[12] Around the square were the palaces of Pachacuti, Huayna Capac and Viracocha Inca.[13]

Palaces

[edit]The square was surrounded by the palaces of the Incas as well as plots of land destined for future palaces. The palace of Pachacuti was called Qasana and was located on the northwest side of the square on the site that today corresponds to the Portal de Panes and is circumscribed by Calle Plateros, Calle Tigre, Calle Teqsecocha and Calle Procuradores. The palace of Huayna Capac was called Amaru Cancha and was located on the southeast side of the square on the site that is now occupied by the Iglesia de la Compañía, the Portal de la Compañía, the University Auditorium and also the Palace of Justice. This site is now circumscribed by the Calle Loreto, Calle Afligidos, Calle Mantas and Avenida El Sol. The palace of the Inca Viracocha called Sunturwasi nowadays corresponds to the block where the Cathedral is located. Additionally, the current Portal de Harinas corresponds to the old palace called Korakora and the Portal de Carrizos to the old Acllawasi.

During the Inca period, this was where almost all the Inca festivals were celebrated, including Inti Raymi, Huarachicuy, the Amaru dance, Capac Raymi, etc. It was also where the main fairs were held and where the victories of the Inca army were celebrated.[14] The Inca armies were received in the Plaza de Armas of Cusco, where the spoils were exhibited and the prisoners of war were trampled as a sign of victory.

Conquest

[edit]When the Spaniards arrived in Cusco, they stayed in the Inca palaces around the square.[15] Later, they built viceroyal mansions, cathedrals, temples and chapels over the Inca palaces. In 1545 the chief magistrate Polo de Ondergardo ordered the removal of the beach sand that was on the floor of the square to use it in the construction of the Cusco Cathedral.[16] In 1555, the chief magistrate of Cuzco, Sebastián Garcilaso de la Vega authorized the construction of buildings in the middle of the Huacaypata thus generating the blocks currently located between Calle Espaderos, Calle Del Medio, Calle Mantas, Calle Heladeros and Calle Espinar as well as the current Plaza de Armas, Plaza Regocijo, Plaza Espinar and the Hotel de Turistas which, during the Viceroyalty served as the Casa de Moneda.[17]

Present day

[edit]At the present time, the Plaza de Armas is surrounded by tourist restaurants, jewelry stores, travel agencies and tourist stores, etc. The two temples built around it are maintained as such during the hours of worship, outside these hours they are museums open to the public upon payment of the corresponding fees.

Most of the buildings still have some Inca walls in their foundations, but it is the colonial style that prevails. The importance of the area makes it the most expensive in the city of Cusco. In some cases the rent of a local exceeds 1500 dollars per month. In the first decade of the 21st century, several national and international franchises entered the Cusco market, opening their first stores in the Plaza de Armas, such as the Peruvian company Bembos and the American companies McDonald's, Starbucks and KFC.[18]

The square is still the place of celebrations of many Cuzco folkloric festivities such as Santiraticuy, Corpus Christi, Easter, etc. and many other modern festivities such as the Fiestas Patrias, Fiestas del Cusco, New Year, etc. Occasionally the Plaza de Armas is the site of some free concerts, parades of delegations and some political rallies.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Angles Vargas (1998, p. 74)

- ^ Angles Vargas (1998, p. 77)

- ^ Relación de monumentos históricos del Perú (PDF) (in Spanish). Lima: Instituto Nacional de Cultura. 1999. p. 37. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ "Ciudad del Cusco" (in Spanish). UNESCO. 19 August 2019.

- ^ Rostworowski de Diez Canseco (2002, p. 83)

- ^ a b c Angles Vargas (1998, p. 82)

- ^ Angles Vargas (1998, p. 87)

- ^ Cortazar (1968, p. 28)

- ^ Espinoza Soriano (1997, p. 87)

- ^ Angles Vargas (1998, p. 89)

- ^ "Huacaypata" (in Spanish). 2011-11-22. Archived from the original on 2011-11-22. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ "Cusco: Urbano Prehispánico". www.peru.travel (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Plaza de Armas-Cusco" (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ Espinoza Soriano (1997, p. 377)

- ^ Cortazar (1968, p. 26)

- ^ Angles Vargas (1998, p. 88)

- ^ Angles Vargas (1983, p. 776)

- ^ Meisner, Hans-Otto. "Locales de McDonald's y KFC abrirán en Cusco" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 April 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

Bibliography

[edit]- Angles Vargas, Victor (1983). Historia del Cusco Cusco Colonial Tomo II Libro Segundo (in Spanish). Lima: Industrial gráfica S.A.

- Angles Vargas, Victor (1998). Historia del Cusco incaico (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). Lima: Industrial gráfica S.A.

- Espinoza Soriano, Waldemar (1997). Los incas (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). Lima: Amaru Editores.

- Cortazar, Pedro Felipe (1968). Documental del Perú: Cuzco (in Spanish). Lima: Iope S.A.

- Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, María (2002). Historia del Tawantinsuyu (in Spanish). FIMART S.A.C. ISBN 9972-51-029-8.