Polyoxometalate

In chemistry, a polyoxometalate (abbreviated POM) is a polyatomic ion, usually an anion, that consists of three or more transition metal oxyanions linked together by shared oxygen atoms to form closed 3-dimensional frameworks. The metal atoms are usually group 6 (Mo, W) or less commonly group 5 (V, Nb, Ta) transition metals in their high oxidation states. They are usually colorless or orange, diamagnetic anions. Two broad families are recognized, isopolymetalates, composed of only one kind of metal and oxide, and heteropolymetalates, composed of one metal, oxide, and a main group oxyanion (phosphate, silicate, etc.). Many exceptions to these general statements exist.[1][2]

Formation

The oxides of d0 metals such as V2O5, MoO3, WO3 dissolve at high pH to give orthometalates, VO3−

4, MoO2−

4, WO2−

4. For Nb2O5 and Ta2O5, the nature of the dissolved species at high pH is less clear, but these oxides also form polyoxometalates.

As the pH is lowered, orthometalates protonate to give oxide–hydroxide compounds such as W(OH)O−

3 and V(OH)O2−

3. These species condense via the process called olation. The replacement of terminal M=O bonds, which in fact have triple bond character, is compensated by the increase in coordination number. The nonobservation of polyoxochromate cages is rationalized by the small radius of Cr(VI), which may not accommodate octahedral coordination geometry.[1]

Condensation of the M(OH)On−

3 species entailss loss of water and the formation of M–O–M linkages. The stoichiometry for hexamolybdate is shown:[3]

- 6 MoO42- + 10 HCl → [Mo6O19]2- + 10 Cl− + 5 H2O

An abbreviated condensation sequence illustrated with vanadates is:[1][4]

- 4 VO3−

4 + 8 H+ → V

4O4−

12 + 4 H2O - 2+1⁄2 V

4O4−

12 + 6 H+ → V

10O

26(OH)4−

2 + 2 H2O

When such acidifications are conducted in the presence of phosphate or silicate, heteropolymetalate result. For example, the phosphotungstate anion PW

12O3−

40 consists of a framework of twelve octahedral tungsten oxyanions surrounding a central phosphate group.

History

Ammonium phosphomolybdate, PMo

12O3−

40 anion, was reported in 1826.[5] The isostructural phosphotungstate anion was characterized by X-ray crystallography 1934. This structure is called the Keggin structure after its discoverer.[6]

The 1970's witnessed the introduction of quaternary ammonium salts of POMs.[3] This innovation enabled systematic study without the complications of hydrolysis and acid/base reactions. The introduction of 17O NMR spectroscopy allowed the structural characterization of POMs in solution.[7]

Ramazzoite, the first example of a mineral with a polyoxometalate cation, was described in 2016 in Mt. Ramazzo Mine, Liguria, Italy.[8]

Structure

The typical framework building blocks are polyhedral units, with 6-coordinate metal centres. Usually, these units share edges and/or vertices. The coordination number of the oxide ligands varies according to their location in the cage. Surface oxides tend to be terminal or doubly briding oxo ligands. Interior oxides are typically triply bridging or even octahedral.[1] POMs are sometimes viewed as soluble fragments of metal oxides.[7]

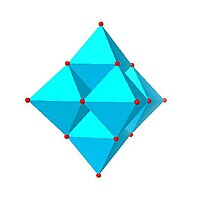

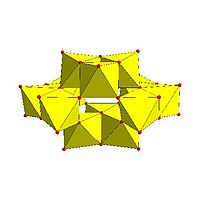

Recurring structural motifs allow POMs to be classified. Iso-polyoxometalates (isopolyanions) feature octahedral metal centers. The heteropolymetalates form distinct structures because the main group center is usually tetrahedral. The Lindqvist and Keggin structures are common motifs for iso- and heteropolyanions, respectively.

|

|

|

|

|

| Lindqvist hexamolybdate, Mo 6O2− 19 |

Decavanadate, V 10O6− 28 |

Line drawing of disodium decavanadate, V 10O6− 28 |

Paratungstate B, H 2W 12O10− 42 |

Mo36-polymolybdate, Mo 36O 112(H 2O)8− 16 |

Polymolybdates and tungstates

The polymolybdates and polytungstates are derived, formally at least, from the dianionic [MO4]2- precursors. The most common units for polymolybdates and polyoxotungstates are the octahedral {MO6} centers, sometimes slightly distorted. Some polymolybdates contain pentagonal bipyramidal units. These building blocks are found in the molybdenum blues, which are mixed valence compounds.[1]

Polyoxotantalates, niobates, and vanadates

The polyniobates, polytantalates, and vanadates are derived, formally at least, from highly charged [MO4]3- precursors. For Nb and Ta, most common members are M

6O8−

19 (M = Nb, Ta), which adopt the Lindqvist structure. These octaanions form in strongly basic conditions from alkali melts of the extended metal oxides (M2O5), or in the case of Nb even from mixtures of niobic acid and alkali metal hydroxides in aqueous solution. The hexatantalate can also be prepared by condensation of peroxotantalate Ta(O

2)3−

4 in alkaline media.[9] These polyoxometalates display an anomalous aqueous solubility trend of their alkali metal salts inasmuch as their Cs+ and Rb+ salts are more soluble than their Na+ and Li+ salts. The opposite trend is observed in group 6 POMs.[10]

The decametalates with the formula M

10O6−

28 (M = Nb,[11] Ta[12]) are isostructural with decavanadate. They are formed exclusively by edge-sharing {MO6} octahedra (the structure of decatungstate W

10O4−

32 comprises edge-sharing and corner-sharing tungstate octahedra).

Heteroatoms

Heteroatoms aside from the transition metal are a defining feature of heteropolymetalates. Many different elements can serve as heteroatoms but most common are PO3−

4, SiO4−

4, and AsO3−

4.

Giant structures

Polyoxomolybdates include the wheel-shaped molybdenum blue anions and spherical keplerates. The cluster [Mo154(NO)14O420(OH)28(H2O)70]~20- consists of more than 700 atoms and is the size of a small protein. The anion is in the form of a tire (the cavity has a diameter of more than 20 Å) and an extremely large inner and outer surface.

Oxoalkoxometalates

Oxoalkoxometalates are clusters that contain both oxide and alkoxide ligands.[13] Typically they lack terminal oxo ligands. Examples include the dodecatitanate Ti12O16(OPri)16 (where OPri stands for an alkoxy group),[14] the iron oxoalkoxometalates[15] and iron[16] and copper[17] Keggin ions.

Sulfido, imido, and other O-replaced oxometalates

The terminal oxide centers of polyoxometalate framework can in certain cases be replaced with other ligands, such as S2−, Br−, and NR2−.[5][18] Sulfur-substituted POMs are called polyoxothiometalates. Other ligands replacing the oxide ions have also been demonstrated, such as nitrosyl and alkoxy groups.[13][19]

Polyfluoroxometalate are yet another class of O-replaced oxometalates.[20]

Other

Numerous hybrid organic–inorganic materials that contain POM cores,[21][22][23]

Illustrative of the diverse structures of POM is the ion CeMo

12O8−

42, which has face-shared octahedra with Mo atoms at the vertices of an icosahedron).[24]

Applications

POMs are employed as commercial catalysts for oxidation of organic compounds.[25][26]

Potential and emerging applications

The range of size, structure, and elemental composition of polyoxometalates leads to a wide range of properties and a corresponding wide range of potential applications. Some of the applications include the following

- "Green" oxidation catalysts as alternatives to chlorine-based wood pulp bleaching processes,[27] a method of decontaminating water,[28] and a method to catalytically produce formic acid from biomass (OxFA process).[29] Polyoxometalates have been shown to catalyse water splitting.[30]

- non-volatile (permanent) storage components, also known as flash memory devices.[31][32] Some POMs exhibit unusual magnetic properties[33] and are being investigated as possible nanocomputer storage devices (see qubits).[34]

- In artificial photosynthesis, polyoxometalates containing copper have been proposed as catalysts for photochemical water splitting and production of solar fuels.[35]

- The catalytic epoxidation of olefins by using modified silver polyoxometalate catalyst (Ag/Ag-POM) and gold catalyst supported on the barium salt of the POM (2% Au/BaPOM) is very important in the chemical industry since epoxides are versatile and important intermediates in the synthesis of many fine chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

- Potential antitumor and antiviral drugs.[36] The Anderson-type polyoxomolybdates and heptamolybdates exhibit activity for suppressing the growth of some tumors. In the case of (NH3Pr)6[Mo7O24], activity appears related to its redox properties.[37][38]

- Magnetism[39] and optical[40] properties of some POMs, and potential medical applications such as antitumor,[41] antibacterial[42] and antiviral uses.

- DrugsPOM with a Wells-Dawson structure can efficiently inhibit amyloid β (Aβ) aggregation in a therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer's Disease.[43]

References

- ^ a b c d e Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-3365-9.

- ^ Pope, M. T. (1983). Heteropoly and Isopoly Oxometalates. New York: Springer Verlag.

- ^ a b Klemperer, W. G. (1990). "Tetrabutylammonium Isopolyoxometalates". Inorganic Syntheses. 27: 74–85. doi:10.1002/9780470132586.ch15.

- ^ Gumerova, Nadiia I.; Rompel, Annette (2020). "Polyoxometalates in solution: speciation under spotlight". Chemical Society Reviews. 49 (21): 7568–7601. doi:10.1039/D0CS00392A. ISSN 0306-0012.

- ^ a b Gouzerh, P.; Che, M. (2006). "From Scheele and Berzelius to Müller: polyoxometalates (POMs) revisited and the "missing link" between the bottom up and top down approaches". L'Actualité Chimique. 298: 9.

- ^ Keggin, J. F. (1934). "The Structure and Formula of 12-Phosphotungstic Acid". Proc. Roy. Soc. A. 144 (851): 75–100. Bibcode:1934RSPSA.144...75K. doi:10.1098/rspa.1934.0035.

- ^ a b Day, V. W.; Klemperer, W. G. (1985). "Metal Oxide Chemistry in Solution: The Early Transition Metal Polyoxoanions". Science. 228: 533–541. doi:10.1126/science.228.4699.533.

- ^ Kampf, Anthony R.; Rossman, George R.; Ma, Chi; Belmonte, Donato; Biagioni, Cristian; Castellaro, Fabrizio; Chiappino, Luigi (April 4, 2018). "Ramazzoite, [Mg8Cu12(PO4)(CO3)4(OH)24(H2O)20][(H0.33SO4)3(H2O)36], the first mineral with a polyoxometalate cation". European Journal of Mineralogy. 30 (4): 182–186. Bibcode:2018EJMin..30..827K. doi:10.1127/ejm/2018/0030-2748. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ Fullmer, L. B.; Molina, P. I.; Antonio, M. R.; Nyman, M. (2014). "Contrasting ion-association behaviour of Ta and Nb polyoxometalates". Dalton Trans. 2014 (41): 15295–15299. doi:10.1039/C4DT02394C. PMID 25189708.

- ^ Anderson, T. M.; Thoma, S. G.; Bonhomme, F.; Rodriguez, M. A.; Park, H.; Parise, J. B.; Alan, T. M.; Larentzos, J. P.; Nyman, M. (2007). "Lithium Polyniobates. A Lindqvist-Supported Lithium−Water Adamantane Cluster and Conversion of Hexaniobate to a Discrete Keggin Complex". Crystal Growth & Design. 7 (4): 719–723. doi:10.1021/cg0606904.

- ^ Graeber, E. J.; Morosin, B. (1977). "The molecular configuration of the decaniobate ion (Nb17O286−)". Acta Crystallographica B. 33 (7): 2137–2143. doi:10.1107/S0567740877007900.

- ^ Matsumoto, M.; Ozawa, Y.; Yagasaki, A.; Zhe, Y. (2013). "Decatantalate—The Last Member of the Group 5 Decametalate Family". Inorg. Chem. 52 (14): 7825–7827. doi:10.1021/ic400864e. PMID 23795610.

- ^ a b Pope, Michael Thor; Müller, Achim (1994). Polyoxometalates: From Platonic Solids to Anti-Retroviral Activity. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-2421-8.

- ^ Day, V. W.; Eberspacher, T. A.; Klemperer, W. G.; Park, C. W. (1993). "Dodecatitanates: a new family of stable polyoxotitanates". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115 (18): 8469–8470. doi:10.1021/ja00071a075.

- ^ Bino, Avi; Ardon, Michael; Lee, Dongwhan; Spingler, Bernhard; Lippard, Stephen J. (2002). "Synthesis and Structure of [Fe13O4F24(OMe)12]5−: The First Open-Shell Keggin Ion". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124 (17): 4578–4579. doi:10.1021/ja025590a. PMID 11971702.

- ^ Sadeghi, Omid; Zakharov, Lev N.; Nyman, May (2015). "Aqueous formation and manipulation of the iron-oxo Keggin ion". Science. 347 (6228): 1359–1362. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1359S. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4620. PMID 25721507.

- ^ Kondinski, A.; Monakhov, K. (2017). "Breaking the Gordian Knot in the Structural Chemistry of Polyoxometalates: Copper(II)–Oxo/Hydroxo Clusters". Chemistry: A European Journal. 23 (33): 7841–7852. doi:10.1002/chem.201605876. PMID 28083988.

- ^ Errington, R. John; Wingad, Richard L.; Clegg, William; Elsegood, Mark R. J. (2000). "Direct Bromination of Keggin Fragments To Give [PW9O28Br6]3−: A Polyoxotungstate with a Hexabrominated Face". Angew. Chem. 39 (21): 3884–3886. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20001103)39:21<3884::AID-ANIE3884>3.0.CO;2-M.

- ^ Gouzerh, P.; Jeannin, Y.; Proust, A.; Robert, F.; Roh, S.-G. (1993). "Functionalization of polyoxomolybdates: the example of nitrosyl derivatives". Mol. Eng. 3 (1–3): 79–91. doi:10.1007/BF00999625.

- ^ Schreiber, Roy E.; Avram, Liat; Neumann, Ronny (2018). "Self-Assembly through Noncovalent Preorganization of Reactants: Explaining the Formation of a Polyfluoroxometalate". Chemistry - A European Journal. 24 (2): 369–379. doi:10.1002/chem.201704287. PMID 29064591.

- ^ Song, Y.-F.; Long, D.-L.; Cronin, L. (2007). "Non covalently connected frameworks with nanoscale channels assembled from a tethered polyoxometalate–pyrene hybrid". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46 (21): 3900–3904. doi:10.1002/anie.200604734. PMID 17429852.

- ^ Guo, Hong-Xu; Liu, Shi-Xiong (2004). "A novel 3D organic–inorganic hybrid based on sandwich-type cadmium heteropolymolybdate: [Cd4(H2O)2(2,2′-bpy)2] Cd[Mo6O12(OH)3(PO4)2(HPO4)2]2 [Mo2O4(2,2′-bpy)2]2·3H2O". Inorganic Chemistry Communications. 7 (11): 1217. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2004.09.010.

- ^ Blazevic, Amir; Rompel, Annette (January 2016). "The Anderson–Evans polyoxometalate: From inorganic building blocks via hybrid organic–inorganic structures to tomorrows "Bio-POM"". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 307: 42–64. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2015.07.001.

- ^ Dexter, D. D.; Silverton, J. V. (1968). "A New Structural Type for Heteropoly Anions. The Crystal Structure of (NH4)2H6(CeMo12O42)·12H2O". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968 (13): 3589–3590. doi:10.1021/ja01015a067.

- ^ Misono, Makoto (1993). "Catalytic chemistry of solid polyoxometalates and their industrial applications". Mol. Eng. 3 (1–3): 193–203. doi:10.1007/BF00999633.

- ^ Kozhevnikov, Ivan V. (1998). "Catalysis by Heteropoly Acids and Multicomponent Polyoxometalates in Liquid-Phase Reactions". Chem. Rev. 98 (1): 171–198. doi:10.1021/cr960400y. PMID 11851502.

- ^ Gaspar, A. R.; Gamelas, J. A. F.; Evtuguin, D. V.; Neto, C. P. (2007). "Alternatives for lignocellulosic pulp delignification using polyoxometalates and oxygen: a review". Green Chem. 9 (7): 717–730. doi:10.1039/b607824a.

- ^ Hiskia, A.; Troupis, A.; Antonaraki, S.; Gkika, E.; Kormali, P.; Papaconstantinou, E. (2006). "Polyoxometallate photocatalysis for decontaminating the aquatic environment from organic and inorganic pollutants". Int. J. Env. Anal. Chem. 86 (3–4): 233. doi:10.1080/03067310500247520.

- ^ Wölfel, R.; Taccardi, N.; Bösmann, A.; Wasserscheid, P. (2011). "Selective catalytic conversion of biobased carbohydrates to formic acid using molecular oxygen". Green Chem. 13 (10): 2759. doi:10.1039/C1GC15434F.

- ^ Rausch, B.; Symes, M. D.; Chisholm, G.; Cronin, L. (2014). "Decoupled catalytic hydrogen evolution from a molecular metal oxide redox mediator in water splitting". Science. 345 (6202): 1326–1330. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1326R. doi:10.1126/science.1257443. PMID 25214625.

- ^ "Flash memory breaches nanoscales", The Hindu.

- ^ Busche, C.; Vila-Nadal, L.; Yan, J.; Miras, H. N.; Long, D.-L.; Georgiev, V. P.; Asenov, A.; Pedersen, R. H.; Gadegaard, N.; Mirza, M. M.; Paul, D. J.; Poblet, J. M.; Cronin, L. (2014). "Design and fabrication of memory devices based on nanoscale polyoxometalate clusters". Nature. 515 (7528): 545–549. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..545B. doi:10.1038/nature13951. PMID 25409147.

- ^ Müller, A.; Sessoli, R.; Krickemeyer, E.; Bögge, H; Meyer, J.; Gatteschi, D.; Pardi, L.; Westphal, J.; Hovemeier, K.; Rohlfing, R.; Döring, J; Hellweg, F.; Beugholt, C.; Schmidtmann, M. (1997). "Polyoxovanadates: High-Nuclearity Spin Clusters with Interesting Host–Guest Systems and Different Electron Populations. Synthesis, Spin Organization, Magnetochemistry, and Spectroscopic Studies". Inorg. Chem. 36 (23): 5239–5240. doi:10.1021/ic9703641.

- ^ Lehmann, J.; Gaita-Ariño, A.; Coronado, E.; Loss, D. (2007). "Spin qubits with electrically gated polyoxometalate molecules". Nanotechnology. 2 (5): 312–317. arXiv:cond-mat/0703501. Bibcode:2007NatNa...2..312L. doi:10.1038/nnano.2007.110. PMID 18654290.

- ^ Buvailo, Halyna; Makhankova, Valeriya G.; Kokozay, Vladimir N.; Omelchenko, Irina V.; Shishkina, Svitlana V.; Jezierska, Julia; Pavliuk, Mariia V.; Shylin, Sergii I. (2019). "Copper-containing hybrid compounds based on extremely rare [V2Mo6O26]6– POM as water oxidation catalysts". Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers. 6 (7): 1813–1823. doi:10.1039/C9QI00040B. ISSN 2052-1553.

- ^ Rhule, Jeffrey T.; Hill, Craig L.; Judd, Deborah A. (1998). "Polyoxometalates in Medicine". Chem. Rev. 98 (1): 327–358. doi:10.1021/cr960396q. PMID 11851509.

- ^ Hasenknopf, Bernold; Bernold; Hasenknopf (2005). "Polyoxometalates: introduction to a class of inorganic compounds and their biomedical applications". Frontiers in Bioscience. 10 (1–3): 275–87. doi:10.2741/1527. PMID 15574368.

- ^ Pope, Michael; Müller, Achim (1994). Polyoxometalates: From Platonic Solids to Anti-Retroviral Activity - Springer. Topics in Molecular Organization and Engineering. Vol. 10. pp. 337–342. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0920-8. ISBN 978-94-010-4397-7.

- ^ Müller, Achim; Luban, Marshall; Modler, Robert; Kögerler, Paul; Axenovich, Maria; Schnack, Jürgen; Canfield, Paul; Budko, Sergey; Harrison, Neil (2001). "Classical and Quantum Magnetism in Giant Keplerate Magnetic Molecules". ChemPhysChem. 2 (8–9): 517–521. doi:10.1002/1439-7641(20010917)2:8/9<517::aid-cphc517>3.0.co;2-1. PMID 23686989.

- ^ Schnack, Jürgen; Brüger, Mirko; Luban, Marshall; Kögerler, Paul; Morosan, Emilia; Fuchs, Ronald; Modler, Robert; Nojiri, Hiroyuki; Rai, Ram C.; Cao, Jinbo; Musfeldt, Janice; Wei, Xing (2006). "Field-dependent magnetic parameters in Ni4Mo12: Magnetostriction at the molecular level?". Phys. Rev. B. 73 (9): 094401. arXiv:cond-mat/0509476. Bibcode:2006PhRvB..73i4401S. doi:10.1103/physrevb.73.094401.

- ^ Bijelic, Aleksandar; Aureliano, Manuel; Rompel, Annette (2019-03-04). "Polyoxometalates as Potential Next‐Generation Metallodrugs in the Combat Against Cancer". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 58 (10): 2980–2999. doi:10.1002/anie.201803868. ISSN 1433-7851. PMC 6391951. PMID 29893459.

- ^ Bijelic, Aleksandar; Aureliano, Manuel; Rompel, Annette (2018). "The antibacterial activity of polyoxometalates: structures, antibiotic effects and future perspectives". Chemical Communications. 54 (10): 1153–1169. doi:10.1039/C7CC07549A. ISSN 1359-7345. PMC 5804480. PMID 29355262.

- ^ Gao, Nan; Sun, Hanjun; Dong, Kai; Ren, Jinsong; Duan, Taicheng; Xu, Can; Qu, Xiaogang (2014-03-04). "Transition-metal-substituted polyoxometalate derivatives as functional anti-amyloid agents for Alzheimer's disease". Nature Communications. 5: 3422. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3422G. doi:10.1038/ncomms4422. PMID 24595206.

Further reading

- Long, D. L.; Burkholder, E.; Cronin, L. (2007). "Polyoxometalate Clusters, Nanostructures and Materials: From Self-Assembly to Designer Materials and Devices". Chem. Soc. Rev. 36 (1): 105–121. doi:10.1039/b502666k. PMID 17173149.

- Pope, M. T.; Müller, A. (1991). "Polyoxometalate Chemistry: An Old Field with New Dimensions in Several Disciplines". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 30: 34–48. doi:10.1002/anie.199100341.

- Hill, C. L. (1998). "Special Volume on Polyoxometalates". Chem. Rev. 98 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1021/cr960395y. PMID 11851497.

- Cronin, L.; Müller, A., eds. (2012). "Special Issue on Polyoxometalates". Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012 (22): 7325–7648. doi:10.1039/C2CS90087D. PMID 23052289.