Rabotnitsa

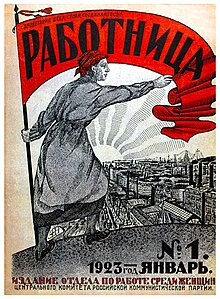

1923 cover of Rabotnitsa | |

| Frequency | Monthly |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1914 |

| Country | Soviet Union/Russia |

| Based in | Moscow |

| Language | Russian |

Rabotnitsa (Russian: Работница; English: The Woman Worker) is a women's journal, published in the Soviet Union and Russia and one of the oldest Russian magazines for women and families. Founded in 1914, and first published on Women's Day, it is the first socialist women's journal,[1] and the most politically left of the women's periodicals.[2] While the journal's beginnings are attributed to Lenin and several women who were close to him, he did not contribute to the first seven issues.[3]

It was re-organized in May 1917 as a Bolshevik journal administered by the Zhenotdel, the Women's Section of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, becoming their central publication. Later that year, its editors organized the First Conference of Working Women of the Petrograd Region, promoting the Bolshevik cause in the elections to the Constituent Assembly.[4] From the start of the Russian Revolution of 1917, Rabotnitsa served as the official women's publication under the Communist Party in Russia.[5]

History

The journal Rabotnitsa was established in 1914[6] in St. Petersburg. While some state it was initiated by Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin's wife,[5] the idea is credited to Konkordiia (née Gromova) Samoilova.[7] Inessa Armand, a close friend of Lenin, was instrumental in actualizing the magazine.[8] Anna Yelizarova-Ulyanova, one of Lenin's sisters, found a press willing to print two issues per month.[3] The first editor was a male, Felix Vasilievich Martsinkevich, while the publisher was a female, D.F. Petrovskaia, the wife of a Bolshevik Duma deputy.[2] Its editorial board was composed of Armand and Samoilova, as well as A. I. Yelizarova-Ulyanova, N. K. Krupskaya, P. F. Kudelli, L. R. Menzhinskaya, Y. F. Rozmirovich, and L. N. Stal. It prospered at the encouragement and support provided by Lenin. It was published by Izdatel'stvo "Pressa" in the Russian language.[9] The money needed to support the publication was collected from women workers.

"[Rabotnitsa] will educate women workers with low [political] conscious. [It] will point out their common interests with the rest of the working class not only in Russia but all around the world." (Rabotnitsa, 23 February 1914)

The first issue was published on International Women's Day, 23 February 1914, with 12,000 copies.[2] It lacked a cover, illustrations and an issuing body.[5] It was a quarterly journal for the period 24 February (8 March) to June 1914. In its first year, its circulation was 12,000. Initially, there were seven issues of which three were confiscated by the police as there was strict censorship by the Communist Party. The magazine ceased its publication after the seven issues due to the difficulties associated with World War I.

The journal restarted on 10 May (23), 1917, its cover announcing that it was now a part of the central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party. Following the October 1917 Revolution, the magazine created a citywide awareness of the revolution. This was followed by the "First All-Russian Congress of Women Workers" in 1918 after which the tsarist government closed the magazine, and all members of the editorial board were jailed.[5] Its publication was resumed in Moscow in January 1923.[10] Ulyanova worked for the magazine at that time, but did not follow the instructions of her brother, Lenin, who by now was abroad, and she resisted efforts by Armand to make the magazine more theoretical.[8]

"Ardent greetings to Rabotnitsa on the tenth anniversary of its existence. I wish it every success in training the masses of proletarian women in the spirit of the struggle for the complete triumph of socialism, in the spirit of carrying out the great behests of our teacher Lenin." (Rabotnitsa, Joseph Stalin, 1933)

In 1926, the magazine published articles about a perceived male resistance to women entering metal and machine-tool work jobs, which were typically dominated by men. Within 10 years the magazine congratulated its readership, stating that women "form more than one quarter of all metal workers and machine construction workers, and almost a quarter of all workers in the coal industry..."[12] In 1933, Joseph Stalin complemented the magazine with a personal greeting.[11] A 1935 issue was on the topic of motherhood; in 1936, that was an article on narcotics easing labour pain; and in 1946, there was an article on new fabrics.[5] For Rabotnitsa, the period between 1914 and 1944 has been described as "the most dramatic and challenging years of its existence", when strong ties were maintained between the press and the political leadership of the country.[13]

Rabotnisa was relaunched in 1996.[14]

Advocacy

Rabotnitsa is one of the oldest Russian language magazines exclusively devoted to women and families.[15] The magazine's basic theme is to advocate proletarian internationalism and international labor solidarity as a means to checkmate imperialism. Its advocacy is for "social justice, the emancipation of women, and worldwide peace."[16] The magazine meant to make women workers aware of the political situation in the country and acted as a catalyst in participation of women in the socialist revolution in Russia.[16][17] The magazine's editors wrote about transforming domestic life through raising the consciousness of men, and blamed social problems on the lingering influence of patriarchy.[7] The magazine paved the way for the women workers to "participate in state and public life and in the building of communism".[16] It was instrumental in awakening the women workers to the political reality of the times and brought them under the party's banner. It also helped in propagating Leninist ideology of the socialist revolution.

Similar publications

Like Krest'yanka ("the peasant woman"), Rabotnitsa's audience was the ordinary woman and not the activist; and these were the only publications that were available both throughout the country as well as throughout the Stalin era for that audience.[12] Rabotnitsa functioned as a women's supplement to Pravda ("truth").[13]

Circulation

The magazine cost four kopeks in 1914,[18] and the circulation that year was 12,000; in 1918, it was between 30,000 and 40,000. By 1930, it was published in bimonthly press runs of 265,000 copies.[7] In 1974, circulation was 12.6 million; and in 1986, it was 13.3 million.[16] In the 1990s, its circulation was reported to be a record high.[13] It began as a bi-weekly pamphlet, evolved into an illustrated weekly,[5] and later became a monthly journal.[12]

Awards and criticism

Rabotnitsa has received many awards, such as the Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1933) and the Order of Lenin (1964).[16]

Criticism from the Bolshevik women readership centered on the magazine being out of touch with its audience. However, this may have been aimed at Armand. Editors preferred stories of interest to women workers, as well as their poetry and fiction, while Armand preferred theoretical and propaganda pieces written by émigré women such as herself.[8] In spite of a poor review of its quality, Soviet women found the magazine to be "a friend, an adviser, a consultant, and an entertainer".

References

- ^ Choi Chatterjee (2002). Celebrating women: gender, festival culture, and Bolshevik ideology, 1910–1939. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8229-4178-1. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Noonan, Norma C. (2001). Encyclopedia of Russian women's movements. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-313-30438-5. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ a b Elwood, R. C. (8 July 2002). Inessa Armand: Revolutionary and Feminist. Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-521-89421-0. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ "Rabotnitsa". University of Toronto. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Catterall, Miriam; Maclaran, Pauline; Stevens, Lorna (2000). Marketing and feminism: current issues and research. Psychology Press. pp. 165, 167, 175–. ISBN 978-0-415-21973-0. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ Jukka Pietiläinen (2008). "Media Use in Putin's Russia". Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics. 24 (3). doi:10.1080/13523270802267906. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Barbara Evans Clements (1997). Bolshevik women. Cambridge University Press. pp. 103, 264, 270–. ISBN 978-0-521-59920-7. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ a b c McDermid, Jane; Hillyar, Anna (January 1999). Midwives of the revolution: female Bolsheviks and women workers in 1917. Taylor & Francis. pp. 63, 67. ISBN 978-1-85728-624-3. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ "Rabotnitsa Работница". East View. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Maria Davidenko (2016). "Multiple femininities in two Russian women's magazines, 1970s–1990s". Journal of Gender Studies. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ a b "J. StalinTo Rabotnitsa". Marxists. 26 January 1933.

- ^ a b c Edmondson, Linda Harriet (2001). Gender in Russian history and culture. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 158, 160–. ISBN 978-0-333-72078-3. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ a b c "Rabotnitsa: The Paradoxical Success of a Soviet Women's Magazine". Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Sian Stephenson (2007). "The Changing Face of Women's Magazines in Russia". Journalism Studies. 8 (4). Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Rabotnitsa". East View. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Rabotnitsa". The Free Dictionary by Farex. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Pravda, no. 25 (26 January 1933). "J. Stalin To Rabotnitsa". Marxists.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ruthchild, Rochelle Goldberg (28 June 2010). Equality & revolution: women's rights in the Russian Empire, 1905–1917. University of Pittsburgh Pre. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8229-6066-9. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

Further reading

- Vavra, Nancy Glick (2002), Rabotnitsa, constructing a Bolshevik ideal: women and the new Soviet state