Recession shapes

Recession shapes or recovery shapes are used by economists to describe different types of recessions and their subsequent recoveries. There is no specific academic theory or classification system for recession shapes; rather the terminology is used as an informal shorthand to characterize recessions and their recoveries.[1] The most commonly used terms are V-shaped (with variations of square-root shaped, and Nike-swoosh shaped), U-shaped, W-shaped (also known as a double-dip recession), and L-shaped recessions, with the COVID-19 pandemic leading to the K-shaped recession (also known as a two-stage recession). The names derive from the shape the economic data – particularly GDP – takes during the recession and recovery.[2]

V-shaped

[edit]

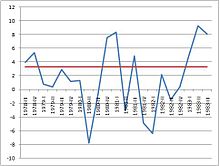

Percent Change in Real GDP (annualized; seasonally adjusted); Average GDP growth 1947–2009

Source: BEA

In a V-shaped recession, the economy suffers a sharp but brief period of economic decline with a clearly defined trough, followed by a strong recovery. V-shapes are the normal shape for a recession, as the strength of the economic recovery is typically closely related to the severity of the preceding recession.[3]

An example of a V-shaped recession is the Recession of 1953 in the United States. In the early 1950s, the economy in the United States was growing, but because the Federal Reserve expected inflation it raised interest rates, tipping the economy into recession. In 1953, growth began to slow in the third quarter and the economy shrank by 2.4 percent. In the fourth quarter, the economy shrank by 6.2 percent, and in the first quarter of 1954, it shrank by 2 percent before returning to growth. By the fourth quarter of 1954, the economy was growing at an 8 percent pace, well above the trend. Thus GDP growth for this recession formed a V-shape.[citation needed]

During the 2020 recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, where the left side of the V was particularly severe, some commentators expected that the recovery might not follow a full V-shape (i.e. right side equal to the drop from the left side), but would look more like a square-root shape, or a Nike-swoosh shape (square-root but with an upward trending right arm).[4] By August 2020, the Federal Reserve was expecting a "bumpy" Nike-swoosh recovery.[5]

U-shaped

[edit]

Percent Change in Real GDP (annualized; seasonally adjusted); Average GDP growth 1947–2009

Source: BEA

A U-shaped recession is longer than a V-shaped recession and has a less-clearly defined trough. GDP may shrink for several quarters, and only slowly return to trend growth. Simon Johnson, former chief economist for the International Monetary Fund, says a U-shaped recession is like a bathtub: "You go in. You stay in. The sides are slippery. You know, maybe there's some bumpy stuff in the bottom, but you don't come out of the bathtub for a long time."[6]

The 1973–75 recession in the United States can be considered a U-shaped recession. In early 1973 the economy began to shrink and continued to decline or have very low growth for nearly two years. After bumping along the bottom, the economy climbed back to recovery in 1975.[1]

W-shaped

[edit]

Percent Change in Real GDP (annualized; seasonally adjusted); Average GDP growth 1947–2009

Source: BEA

Inverted yield curve twice in a row in the late 1970s and early 1980s

In a W-shaped recession (also known as a double-dip recession), the economy falls into recession, recovers with a short period of growth, then falls back into recession before finally recovering, giving a "down up down up" pattern resembling the letter W.

The early 1980s recession in the United States is cited as an example of a W-shaped recession. The National Bureau of Economic Research considers two recessions to have occurred in the early 1980s.[7] The economy fell into recession from January 1980 to July 1980, shrinking at an 8 percent annual rate from April to June 1980. The economy then entered a quick period of growth, and in the first three months of 1981 grew at an 8.4 percent annual rate. As the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker raised interest rates to fight inflation, the economy dipped back into recession (hence, the "double-dip") from July 1981 to November 1982. The economy then entered a period of mostly robust growth for the rest of the decade.

The European debt crisis in the early-2010s is a more recent example of a W-shaped recession. A combination of government austerity, falling business investment, rising interest rates, global economic weakness, high energy prices, and weak consumer spending after the Great Recession of 2008–2009 tipped many Eurozone countries into a second recession from 2011 to 2013. Countries affected included Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, Ireland, Germany and Cyprus. Greece, while part of the Eurozone, saw continuous economic contraction from 2007 to 2015, and thus does not fit the definition of a W-shaped recession, but rather an L-shaped recession. The United Kingdom is not a member of the Eurozone, but was a member of the European Union until 2020, and suffered a minor W-shaped recession when GDP contracted in Q4 2011 and Q1 2012.

L-shaped

[edit]

Percent Change in Real GDP (annualized; seasonally adjusted);

Average GDP growth 1950–2000

Source: Penn World Tables

An L-shaped recession or depression occurs when an economy has a severe recession and does not return to trend line growth[8] for many years, if ever. The steep decline, is followed by a flat line makes the shape of an L. This is the most severe of the different shapes of recession. Alternative terms for long periods of underperformance include "depression" and "lost decade"; compare also "malaise".

A classic example of an L-shaped recession occurred in Japan following the bursting of the Japanese asset price bubble in 1990. From the end of World War II throughout the 1980s, Japan's economy was growing robustly. In the late 1980s, a massive asset-price bubble developed in Japan. After the bubble burst the economy suffered from deflation, and experienced years of sluggish growth; never returning to the higher growth Japan experienced from 1950 to 1990. After the late-2000s recession in the United States followed a similar economic bubble (the United States housing bubble) some economists feared the U.S. economy could enter a prolonged period of low growth even after recovering from the recession.[9] By 2013, however, U.S. GDP growth rebounded, allaying fears of stagnation.

The Greek recession of 2007–2016 could be considered an example of an L-shaped recession, as Greek GDP growth in 2017 was merely 1.6%. Greece technically suffered through four separate, but compounding, periods of contractions over the nine-year period.

K-shaped

[edit]A K-shaped recession (or two-stage recession), is where parts of society experiences more of a V-shaped recession, while other parts of society experience a slower more protracted L-shaped recession (the shape of the K denoting the divergence in the recovery paths).[2]

The term arose from the economic recovery post the COVID-19 pandemic, where central banks had used exceptional monetary tools to generate asset bubbles that protected the wealthier segments of society (i.e. asset-owning), from the financial effects of the pandemic.[2][10] K-shaped recoveries are controversial, and the 2020 K-shaped recovery in the United States led to levels of wealth inequality not seen since the 1920s.[11][12][13] In December 2020, Bloomberg News called 2020, "... a great year for Wall Street, but a bear market for humans".[14] In January 2021, Edward Luce of the Financial Times warned that Jerome Powell's explicit use of asset bubbles in creating a K-shaped recovery, and the resultant widening of wealth inequality, could lead to political and social instability in the United States, saying: "The majority of people are suffering amid a Great Gatsby–style boom at the top".[15]

The top 10 per cent of Americans own 84 percent of the country's shares. The top 1 percent own about half. The bottom half of Americans—the ones who have chiefly been on the frontline during the pandemic—say they own almost no stocks at all.

— Financial Times, "America's Dangerous Reliance on the Fed" (January 2021)[15]

Others

[edit]- Inverted square root: Financier George Soros said the 2009 recession could follow an "inverted square root sign"–shaped recession. Soros explained to Reuters that this meant: "You hit bottom and you automatically rebound some (i.e. a spike), but then you don't come out of it in a V-shape recovery or anything like that. You settle down—step down".[16] Soros actually meant reverse instead of "inverted" square root shape of economic recovery. A similar shape of recovery was observed during the COVID-19 pandemic induced economic crisis.[17]

- Normal square root: During the COVID-19 pandemic, several commentators used the shape of a normal square root to describe a situation where the recovery would not be complete (as per a V-shaped recovery), but after an initial rise, would flatline for a period.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Martha C. White (January 12, 2009). "This Recession Was Brought to You by the Letters U, V and L". The Big Money. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Hauk, William (13 October 2020). "Will it be a 'V' or a 'K'? The many shapes of recessions and recoveries". The Conversation. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ James Morley (April 27, 2009). "The Shape of Things to Come" (PDF). Macro Focus. Vol. 4, no. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Ip, Greg (1 July 2020). "A Recovery That Started Out Like a V Is Changing Shape". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Reuters Staff (28 August 2020). "Fed's Harker sees shape of recovery as 'bumpy swoosh'". Reuters. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "What Shape Is Your Recession". FP. October 12, 2010. (U, V, W, L)

- ^ "NBER Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". NBER.

- ^ Rampell, Catherine (31 Oct 2009). "The Shape of a Recession". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ Nouriel Roubini (April 7, 2008). "The US Recession: V or U or W or L-Shaped?". RGE Monitor. Archived from the original on July 17, 2009.

- ^ Authers, John (11 June 2020). "Powell's Ready to Play the Fresh Prince of Bubbles". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ Cox, Jeff (4 September 2020). "Worries grow over a K-shaped economic recovery that favors the wealthy". CNBC. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ FT Alphaville (19 August 2020). "Yet another 'K-shaped' recovery data point". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Rabouin, Dion (13 October 2020). "Jerome Powell's ironic legacy on economic inequality". Axios. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "2020 Has Been a Great Year for Stocks and a Bear Market for Humans". Bloomberg News. 21 December 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ a b Luce, Edward (3 January 2021). "America's Dangerous Reliance on the Fed". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ Ablan, Jennifer; Burns, Daniel (6 April 2009). "Soros says U.S. faces 'lasting slowdown'". Reuters. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Are we seeing a 'reverse square root' symbol economic recovery?". fortune.com.

Further reading

[edit]- "U, V or W for recovery". The Economist. August 22, 2009. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

External links

[edit]- V-Shaped Recovery, Investopedia (September 2020)

- U-Shaped Recovery, Investopedia (September 2020)

- W-Shaped Recovery, Investopedia (September 2020)

- L-Shaped Recovery, Investopedia (September 2020)

- K-Shaped Recovery, Investopedia (November 2020)