Regular script

| Regular script | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | Bronze Age China, Iron Age China, Present day |

| Languages | Old Chinese, Middle Chinese, Modern Chinese |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Kanji Kana Hanja Zhuyin Simplified Chinese Chu Nom Khitan script Jurchen script Tangut script Nü Shu |

| Unicode | |

| 4E00–9FFF, 3400–4DBF, 20000–2A6DF, 2A700–2B734, 2F00–2FDF, F900–FAFF | |

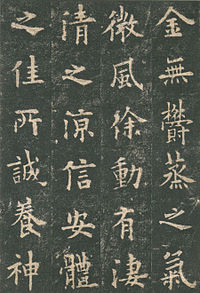

Regular script (traditional Chinese: 楷書; simplified Chinese: 楷书; pinyin: kǎishū; Hepburn: kaisho), also called 正楷 (pinyin: zhèngkǎi), 真書 (zhēnshū), 楷體 (kǎitǐ) and 正書 (zhèngshū), is the newest of the Chinese script styles (appearing by the Cao Wei dynasty ca. 200 CE and maturing stylistically around the 7th century), hence most common in modern writings and publications (after the Ming and gothic styles, used exclusively in print).

History

Regular script came into being between the Eastern Hàn and Cáo Wèi dynasties,[1] and its first known master was Zhōng Yáo (sometimes also read Zhōng Yóu; 鍾繇),[2] who lived in the E. Hàn to Cáo Wèi period, ca. 151–230 CE. He is known as the “father of regular script”, and his famous works include the Xuānshì Biǎo (宣示表), Jiànjìzhí Biǎo (薦季直表), and Lìmìng Biǎo (力命表). Qiu Xigui[1] describes the script in Zhong’s Xuānshì Biǎo as:

…clearly emerging from the womb of early period semi-cursive script. If one were to write the tidily written variety of early period semi-cursive script in a more dignified fashion and were to use consistently the pause technique (dùn 頓, used to reinforce the beginning or ending of a stroke) when ending horizontal strokes, a practice which already appears in early period semi-cursive script, and further were to make use of right-falling strokes with thick feet, the result would be a style of calligraphy like that in the "Xuān shì biǎo".

However, other than a few literati, very few wrote in this script at the time; most continued writing in neo-clerical script, or a hybrid form of semi-cursive and neo-clerical.[1] Regular script did not become dominant until the early Southern and Northern Dynasties, in the 5th century; this was a variety of regular script which emerged from neo-clerical as well as from Zhong Yao's regular script,[3] and is called "Wei regular" (魏楷 Weikai). Thus, regular script has parentage in early semi-cursive as well as neo-clerical scripts.

The script is considered to have matured stylistically during the Tang Dynasty, with the most famous and oft-imitated regular script calligraphers of that period being:

- The early Tang four great calligraphers (初唐四大家):

- Ouyang Xun (欧阳询)

- Yu Shinan (虞世南)

- Chu Suiliang (褚遂良)

- Xue Ji (薛稷)

- "Yan-Liu" ("顏柳")

- Yan Zhenqing (颜真卿)

- Liu Gongquan (柳公权)

Characteristics

Regular script characters with width (or length) larger than 5 cm (2 in) is usually considered larger regular script, or dakai (大楷), and those smaller than 2 cm (0.8 in) usually small regular script, or xiaokai (小楷). Those in between are usually called medium regular script, or zhongkai (中楷). What these are relative to other characters. The Eight Principles of Yong are said to contain a variety of most of the strokes found in regular script.

Notable writings in regular script include:

- The Records of Yao Boduo Sculpturing (姚伯多造像記) during the Southern and Northern Dynasties

- The Tablet of Guangwu General (廣武將軍碑) during the Southern and Northern Dynasties

- The Tablet of Longzang Temple (龍藏寺碑) of the Sui Dynasty

- Tombstone-Record of Sui Xiaoci (蘇孝慈墓誌) of the Sui Dynasty

- Tombstone-Record of Beauty Tong (董美人墓誌) of the Sui Dynasty

- Sweet Spring at Jiucheng Palace (九成宮醴泉銘) of the Tang Dynasty

Derivatives

- Imitation Song typefaces (Chinese: 仿宋體; pinyin: fǎng Sòngtǐ) are typefaces based on a printed style which developed in the Song dynasty, from which Ming typefaces developed.

- The most common printed typeface styles Ming and sans-serif are based on the structure of regular script.

- The Japanese textbook typefaces (教科書体; Hepburn: kyōkashotai) are based on regular script, but modified so that they appear to be written with a pencil or pen. They also follow the standardized character forms prescribed in the Jōyō kanji.

- Zhuyin Fuhao characters, although not true Chinese characters, are virtually always written with regular script strokes.

Regular script in computing

References

- Qiu Xigui (2000). Chinese Writing. Translation of 文字學概論 by Mattos and Norman. Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-071-7.

External links

- Regular Script "tao te king" CHAPTER LVII

- More on Standard Script In English, at BeyondCalligraphy.com