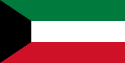

Republic of Kuwait

Republic of Kuwait جمهورية الكويت | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1990 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Puppet state of Ba'athist Iraq | ||||||||

| Capital | Kuwait City | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic | ||||||||

| Government | Ba'athist Military dictatorship | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

| Historical era | Persian Gulf War | ||||||||

• Established | August 4 1990 | ||||||||

• Annexed by Iraq | August 8 1990 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | KW | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Republic of Kuwait was a short-lived and self-styled republic formed in the aftermath of the invasion of Kuwait by Ba'athist Iraq during the early stages of the Persian Gulf War. During the invasion, the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council stated that it had sent troops into the State of Kuwait in order to assist an internal coup d'état initiated by "Kuwaiti revolutionaries."[1] A Provisional Government of Free Kuwait was set up on August 4 by the Iraqi authorities under the leadership of 9 allegedly Kuwaiti military officers (4 colonels and 5 majors) led by Alaa Hussein Ali, who was given the posts of Head of State (Rais al-Wuzara), commander-in-chief, minister of defense and minister of the interior.[2]

The new regime deposed the Emir Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah (who fled Kuwait and established a Government in exile based in Saudi Arabia,[3]) and accused the royal family of pursuing "anti-popular," "anti-democratic," pro-"imperialist" and "Zionist" policies along with the "embezzlement of national resources for the purpose of personal enrichment."[4] An indigenous Popular Army to allegedly take over from Iraqi troops was immediately proclaimed, claiming 100,000 volunteers.[5] Citizenship rights were conferred to non-Kuwaiti Arabs who had come for work from abroad under the monarchy.[6] The newspaper of the regime was known as Al-Nida,[7] named after the "Day of the Call" proclaimed on August 2 to "commemorate" the Iraqi "response" to the alleged calls of the Kuwaitis for Iraq's assistance in overthrowing the monarchy.[8]

History

Walid Saud Abdullah, who was placed in charge of foreign affairs, achieved some notoriety for the provisional regime when on August 5 when he stated that "countries that resort to punitive measures against the provisional free Kuwait government . . . should remember that they have interests and nationals in Kuwait . . . . If these countries insist on aggression against Kuwait and Iraq, the Kuwaiti government will then reconsider the method of dealing with these countries."[9] Saddam's half-brother, Sabawi Ibrahim al-Tikriti of the Iraqi Intelligence Service, was sent on August 4 to establish a security system similar to Iraq's own.[10]

The regime and the Iraqi Government failed in attempts to persuade Kuwaiti opposition groups to partake in the new puppet government, and instead these groups threw their support behind the monarchy.[11][12] Iraq initially claimed that its presence in Kuwait would be limited to helping to foster "a new era of freedom, democracy, justice, and real prosperity in the society," and promised to leave Kuwait once the provisional regime deemed its internal security situation secure[13] which was estimated to take only weeks.[14] International condemnation of Iraq's invasion and a lack of support for the new regime amongst the Kuwaiti citizenry quickly rendered it nonviable.

On August 7 the "Provisional Government of Free Kuwait" proclaimed itself as a republic, with Hussein Ali as its Prime Minister.[15] A day later the Iraqi Government declared a "merger" of Iraq and Kuwait, based on historical claims.[16] The Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council released a statement stating that: "The free provisional Kuwaiti government has decided to appeal to kinsfolk in Iraq, led by the knight of Arabs and the leader of their march, President Field Marshal Saddam Hussein, to agree that their sons should return to their large family, that Kuwait should return to the great Iraq—the mother homeland—and to achieve complete merger unity between Kuwait and Iraq."[17] Hussein Ali was then made Deputy Prime Minister of Iraq while Ali Hassan al-Majid was proclaimed Governor. The Turkish daily Milliyet reported Hussein in September 1990 saying to Bülent Ecevit that, "Kuwait is now ours, but we might have refrained from taking such a decision if U.S. troops were not massed in the region with the threat of invading us." He also said on the subject of the short-lived provisional regime that had the U.S. not opposed Iraq, Iraq "would have attempted to develop the status of the temporary revolutionary administration," and that, "We would not have been able to ask our people and the armed forces to fight to the last drop of blood if we had not said that Kuwait was not part of Iraq. We would not have been able to prepare our people for the possibility of war."[18]

On August 28, 1990, the Kuwaiti territory was transformed into the Kuwait Governorate, Iraq's 19th province, and thus it was formally annexed. Iraq's refusal to withdraw from Kuwait led to the Persian Gulf War, and on 26 February 1991 the pre-occupation government was returned to power.

Cabinet

- Prime Minister, Defense Minister and acting Interior Minister: Col. Ala'a Hussein Ali al-Khafaji al-Jaber

- Minister of Foreign Affairs: Lt. Col. Walid Sa'ud Muhammad Abdullah

- Minister of Oil and acting Finance Minister: Lt. Col. Fu'ad Hussein Ahmad

- Minister of Information and acting Transport Minister: Maj. Fadil Haydar al-Wafiqi

- Minister of Public Health and Housing: Maj. Mish'al Sa'd al-Hadab

- Minister of Social Affairs and acting Works and Labour Minister: Lt. Col. Hussein Ali Duhayman al-Shammari

- Minister of Education and acting Minister of Higher Education: Maj. Nasir Mansur al-Mandil

- Minister of Justice and Legal Affairs and acting minister of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs: Maj. Isam Abd al-Majid Hussein

- Minister of Trade, Electricity and Planning: Maj. Ya'qub Muhammad Shallal

See Also

References

- ^ Clive H. Schofield & Richard N. Schofield (Ed.). The Middle East and North Africa. New York: Routledge. 1994. p. 147.

- ^ Newsweek Vol. 116. 1990. p. 20.

- ^ Michael S. Casey. The History of Kuwait. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 2007. p. 93.

- ^ Daily Report: Soviet Union. Issues 147-153. 1990. p. 124.

- ^ Jerry Mark Long. Saddam's War of Words: Politics, Religion, and the Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 2004. p. 27.

- ^ Dilip Hiro. Desert Shield to Desert Storm: The Second Gulf War. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, Inc. 2003. p. 105.

- ^ Human Rights Watch World Report 1992: Events of 1991. New York: Human Rights Watch. 1991. p. 652.

- ^ Itamar Rabinovich and Haim Shaked (Ed.). Middle East Contemporary Survey Vol. 14. Oxford: Westview Press. 1990. p. 403.

- ^ Quoted in Yossi Shain, Juan José Linz and Lynn Berat. Between States: Interim Governments and Democratic Transitions. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1995. p. 113.

- ^ Ibrahim Al-Marashi and Sammy Salama. Iraq's Armed Forces: An Analytical History. New York: Routledge. 2008. p. 177.

- ^ Malcolm B. Russell. The Middle East and South Asia: 2008. West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. 2008. p. 112.

- ^ Christian Koch & David E. Long (Ed.). Gulf Security in the Twenty-First Century. Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research. 1997. pp. 217-218.

- ^ Rabinovich and Shaked, p. 403.

- ^ Efraim Karsh and Inari Rautsi. Saddam Hussein: A Political Biography. New York: Grove Press. 1991. p. 221.

- ^ Richard Alan Schwartz. The 1990s. New York: Facts on File, Inc. 2006. p. 74.

- ^ Dale W. Jacobs (Ed.). World Book Focus on Terrorism. Chicago, IL: World Book, Inc. 2002. p. 17.

- ^ Quoted in Lawrence Freedman. A Choice of Enemies: America Confronts the Middle East. New York: PublicAffairs. 2008. pp. 217-218. See also Rabinovich and Shaked, pp. 403-404.

- ^ Paul William Roberts. The Demonic Comedy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 1997. p. 109.

- ^ Richard N. Schofield (Ed.). The Iraq-Kuwait Dispute Vol. 6. Farnham Common: Archive Editions. 1994. p. 821.