Resolution independence

Resolution independence is where elements on a computer screen are rendered at sizes independent from the pixel grid, resulting in a graphical user interface that is displayed at a consistent size, regardless of the size of the screen.

Concept

As early as 1978, the typesetting system TeX due to Donald Knuth introduced resolution independence into the world of computers. The intended view can be rendered beyond the atomic resolution without any artifacts, and the automatic typesetting decisions are guaranteed to be identical on any computer up to an error less than the diameter of an atom. This pioneering system has a corresponding font system, Metafont, which provides suitable fonts of the same high standards of resolution independence.

The terminology Device independent file format is the file format of Donald Knuth's pioneering TeX system. The content of such a file can be interpreted at any resolution without any artifacts, even at very high resolutions not currently in use.

Implementation

OS X

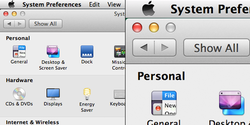

Apple included some support for resolution independence in early versions of OS X (formerly Mac OS X), which could be demonstrated with the developer tool Quartz Debug that included a feature allowing the user to scale the interface. However, the feature was incomplete, as some icons did not show (such as in System Preferences), user interface elements were displayed at odd positions and certain bitmap GUI elements were not scaled smoothly.[1] Because the scaling feature was never completed, OS X's user interface remained resolution-dependent.

On June 11, 2012, Apple introduced the 2012 MacBook Pro with a resolution of 2880×1800 or 5.2 megapixels - doubling the pixel density in both dimensions.[2] The laptop shipped with a version of OS X that provided support to scale the user interface twice as big as it has been previously been. This feature is called HighDPI mode in OS X and it uses a fixed scaling factor of 2 to increase the size of the user interface for high-DPI screens. Apple also introduced support for scaling the UI by rendering the user interface on higher or smaller resolution that the laptop's built-in native resolution and scaling the output to the laptop screen. One obvious downside of this approach is either a decreased performance on rendering the UI on a higher than native resolution or increased blurriness when rendering lower than native resolution. Thus, while the OS X's user interface can be scaled using this approach, the UI itself is not resolution-independent.

Microsoft Windows

The GDI system in Windows is pixel-based and thus not resolution-independent. To scale up the UI, Microsoft Windows has supported specifying a custom DPI from the Control Panel since Windows 95.[3] (In Windows 3.1, the DPI setting is tied to the screen resolution, depending on the driver information file.) When a custom system DPI is specified, the built-in UI in the operating system scales up. Windows also includes APIs for application developers to design applications that will scale properly.

GDI+ in Windows XP adds resolution-independent text rendering [4] however, the UI in Windows versions up to Windows XP is not completely high-DPI aware [5] as displays with very high resolutions and high pixel densities were not available in that time frame. Windows Vista and Windows 7 scale better at higher DPIs.

Windows Vista also adds support for programs to declare themselves to the OS that they are high-DPI aware via a manifest file or using an API.[6][7] For programs that do not declare themselves as DPI-aware, Windows Vista supports a compatibility feature called DPI virtualization so system metrics and UI elements are presented to applications as if they are running at 96 DPI and the Desktop Window Manager then scales the resulting application window to match the DPI setting. Windows Vista retains the Windows XP style scaling option which when enabled turns off DPI virtualization (blurry text) for all applications globally.

Windows Vista also introduces Windows Presentation Foundation. WPF applications are vector-based, not pixel-based and are designed to be resolution-independent.

Windows 7 adds the ability to change the DPI by doing only a log off, not a full reboot and makes it a per-user setting. Additionally, Windows 7 reads the monitor DPI from the EDID and automatically sets the DPI value to match the monitor's physical pixel density, unless the effective resolution is less than 1024 x 768.

In Windows 8, only the DPI scaling percentage is shown in the DPI changing dialog and the display of the raw DPI value has been removed.[8] In Windows 8.1, the global setting to disable DPI virtualization (use XP-style scaling) is removed.[8] DPI virtualization is enabled for all applications at pixel densities higher than 120 PPI (125%). Windows 8.1 retains a per-application option to use XP-style scaling and disable DPI virtualization.[8] Windows 8.1 also adds the ability for each display to use an independent DPI setting.

Android

Since Android 1.6 (Donut, September 2009)[9] Android has provided support for multiple screen sizes and densities. Android expresses layout dimensions and position via the density-independent pixel or "dp" which is defined as one physical pixel on a 160 dpi screen. At runtime, the system transparently handles any scaling of the dp units, as necessary, based on the actual density of the screen in use.[10]

To aid in the creation of underlying bitmaps, Android categorizes resources based on screen size and density:

Linux desktop environments

In 2013, the GNOME desktop environment began efforts to bring resolution independence ("hi-DPI" support) for various parts of the graphics stack. Developer Alexander Larsson initially wrote[11] about changes required in GTK+, Cairo, Wayland and the GNOME themes. At the end of the BoF sessions at GUADEC 2013, GTK+ developer Matthias Clasen mentioned that hi-DPI support would be "pretty complete" in GTK 3.10[12] once work on Cairo would be completed. As of January 2014, hi-DPI support for Clutter and GNOME Shell is ongoing work.[13][14][15][16]

Other

Although not related to true resolution independence, some other operating systems use GUIs that are able to adapt to changed font sizes. Microsoft Windows 95 onwards used the Marlett TrueType font in order to scale some window controls (close, maximize, minimize, resize handles) to arbitrary sizes. AmigaOS from version 2.04 (1991) was able to adapt its window controls to any font size.[failed verification]

Video games are often resolution-independent; an early example is Another World for DOS, which used polygons to draw its 2D content and was later remade using the same polygons at a much higher resolution. 3D games are resolution-independent since the perspective is calculated every frame and so it can vary its resolution.

See also

- Adobe Illustrator

- CorelDRAW

- Direct2D

- Display PostScript

- Himetric

- Inkscape

- Page zooming

- Responsive Web Design

- Retina display

- Scalable Vector Graphics

- Synfig

- Twips

- Vector graphics

References

- ^ Apple (April 29, 2005). "Resolution Independent UI Release Notes for Mac OS X v10.4". Apple Developer Connection. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ^ Anand Lal Shimpi (June 11, 2012). "MacBook Pro Retina Display Analysis". AnandTech. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- ^ Where does 96 DPI come from in Windows?

- ^ Why text appears different when drawn with GDIPlus versus GDI

- ^ Windows XP and Windows 2000 do not natively support high-DPI screens

- ^ "Win32 SetProcessDPIAware Function".

- ^ "Windows Vista DPI Settings".

- ^ a b c High DPI Settings in Windows

- ^ http://developer.android.com/about/versions/android-1.6-highlights.html

- ^ http://developer.android.com/guide/practices/screens_support.html

- ^ http://blogs.gnome.org/alexl/2013/06/28/hidpi-support-in-gnome/

- ^ http://blogs.gnome.org/mclasen/2013/08/07/gtk-meeting-notes/

- ^ https://wiki.gnome.org/ThreePointNine/Features/Hidpi

- ^ https://bugzilla.gnome.org/show_bug.cgi?id=705915

- ^ https://bugzilla.gnome.org/show_bug.cgi?id=705410

- ^ https://bugzilla.gnome.org/show_bug.cgi?id=705411

External links

- Declaration of resolution-independence by John Siracusa