Robert Stroud

Robert Franklin Stroud | |

|---|---|

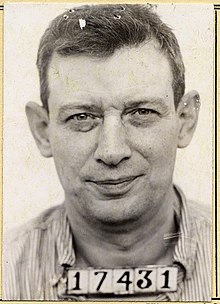

Robert Stroud in 1951 | |

| Born | January 28, 1890 Seattle, Washington, United States |

| Died | November 21, 1963 (aged 73) Springfield, Missouri, United States |

| Other names | "Birdman of Alcatraz" |

| Occupations |

|

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Spouse | Della Mae Jones |

| Parent(s) | Benjamin Stroud Elizabeth Stroud |

| Criminal charge |

|

| Penalty |

|

Robert Franklin Stroud (January 28, 1890 – November 21, 1963), known as the "Birdman of Alcatraz", was an American federal prisoner and author who has been cited as one of the United States' most notorious criminals.[1][2][3] During his time at Leavenworth Penitentiary, he reared and sold birds and became a respected ornithologist, but because of regulations, he was not permitted to keep birds at Alcatraz, where he was incarcerated from 1942 to 1959. Stroud was never released from the Federal prison system.

Born in Seattle, Washington, Stroud ran away from his abusive father at the age of 13, and by the time he was 18, he had become a pimp in the Alaska Territory. In January 1909, he shot and killed a bartender who had attacked one of his prostitutes, for which he was sentenced to 12 years in the federal penitentiary on Puget Sound's McNeil Island. Stroud gained a reputation as an extremely dangerous inmate who frequently had confrontations with fellow inmates and staff, and in 1916, he killed a guard. Stroud was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to hang, but after several trials, his sentence was eventually commuted to life imprisonment.

Stroud began serving life in solitary confinement at Leavenworth, where in 1920, after discovering a nest with three injured sparrows in the prison yard, he began raising them, and within a few years had acquired a collection of some 300 canaries. He began extensive research into them after being granted equipment by a radical prison-reforming warden, publishing Diseases of Canaries in 1933, which was smuggled out of Leavenworth and sold en masse,[4] as well as a later edition (1943). He made important contributions to avian pathology, most notably a cure for the hemorrhagic septicemia family of diseases, gaining much respect and some level of sympathy among ornithologists and farmers. Stroud ran a successful business from inside prison, but his activities infuriated the prison staff, and he was eventually transferred to Alcatraz in 1942 after it was discovered that Stroud had been secretly making alcohol using some of the equipment in his cell.

Stroud began serving a 17-year term at Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary on December 19, 1942, and became inmate #594. In 1943, he was assessed by psychiatrist Romney M. Ritchey, who diagnosed him as a psychopath, but with an I.Q. of 134. Stripped of his birds and equipment, he wrote a history of the penal system.

In 1959, with his health failing, Stroud was transferred to the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri, where he stayed until his death on November 21, 1963, having been incarcerated for the last 54 years of his life, of which 42 were in solitary confinement. He had been studying French near the end of his life. Robert Stroud is buried in Metropolis, Illinois. Author Carl Sifakis considers Stroud to have been "possibly the best-known example of self-improvement and rehabilitation in the U.S. prison."

Early life and arrest

Stroud was born in Seattle, the eldest child of Elizabeth Jane (née McCartney 1860-1938) and Benjamin Franklin Stroud. His mother had two daughters from a previous marriage. His father was an abusive alcoholic, and Stroud ran away from home at the age of 13. His parents both had German ancestry.[5]

By the time he was 18, Stroud had made his way to Cordova, Alaska, where he met 36-year-old Kitty O’Brien, a prostitute and dance-hall entertainer, for whom he pimped in Juneau. According to Stroud, on January 18, 1909, while he was away at work, an acquaintance of theirs, barman F. K. "Charlie" Von Dahmer, had allegedly failed to pay O'Brien for her services and beat her, tearing a locket from her neck that contained a picture of her daughter that was of sentimental value.[6][7] That night, after finding out about the incident, Stroud confronted Von Dahmer on Gastineau Avenue, and a struggle ensued, resulting in the latter's death from a gunshot wound. Stroud went to the police station, and turned himself and the gun in.[7] According to police reports, Stroud had knocked Von Dahmer unconscious, and then shot him at point-blank range.

Stroud's mother, Elizabeth, retained a lawyer for her son, but he was found guilty of manslaughter on August 23, 1909, and sentenced to 12 years in the federal penitentiary on Puget Sound's McNeil Island.[5] Stroud's crime was handled in the federal system, as Alaska at that time was still a federal territory, and not a state with its own judiciary system.

Prison life

Known as Prisoner #1853-M, Stroud was one of the most violent prisoners at McNeil Island, frequently feuding with fellow inmates and staff, and was also prone to many different physical ailments.[8] Stroud reportedly stabbed a fellow prisoner who had reported him for stealing food from the kitchen.[7] He also assaulted a hospital orderly who had reported him to the prison administration for attempting to obtain morphine through threats and intimidation, and had also reportedly stabbed another fellow inmate who was involved in the attempt to smuggle the narcotics. On September 5, 1912, Stroud was sentenced to an additional six months for the attacks, and was transferred from McNeil Island to the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. On March 26, 1916,[5] after being there six months, Stroud was reprimanded by cafeteria guard Andrew F. Turner for a minor rule violation that would have annulled Stroud's visitation privilege to meet his younger brother, whom he had not seen in eight years. With a six-inch shiv, Stroud stabbed Turner through his heart.[9][7]

Stroud was convicted of first-degree murder, and sentenced to death by hanging on May 2.[5] He was ordered to await execution of his sentence in solitary confinement, but this was thrown out in December by the U.S. Supreme Court. In a second trial held on May 28, 1917, he was also convicted, but received a life sentence, which Stroud appealed, and Solicitor General John W. Davis "confessed error" because he wanted Stroud to receive the death penalty.[10] As a result, Stroud was tried for a third time in May 1918, and on June 28 he was again sentenced to death by hanging.[10] The Supreme Court intervened, upholding the death sentence, which was scheduled to be carried out on April 23, 1920. Stroud's mother appealed to President Woodrow Wilson and his wife, Edith Wilson, and the execution was halted just eight days before it was to be carried out; the gallows had already been built and viewed by Stroud from his cell.[11][10] Stroud's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Leavenworth's warden, T. W. Morgan, strongly opposed the decision given Stroud's reputation for violence. Morgan persuaded the President to stipulate that since Stroud was originally sentenced to await his death sentence in solitary confinement, those conditions should prevail until the halted execution could be carried out. President Wilson's Attorney General, Alexander Mitchell Palmer, saw to it that Stroud was sentenced to a lifetime in solitary.[12][4]

The Birdman of Leavenworth

While at Leavenworth in 1920, Stroud found a nest with three injured sparrows in the prison yard, and raised them to adulthood.[4] Prisoners were sometimes allowed to buy canaries, and Stroud had started to add to his collection to occupy his time raising and caring for his birds, which he could sell for supplies and to help support his mother. According to Stroud, he used a "razor blade and nail for tools" and made his first bird cage out of wooden crates.[13] Soon thereafter, Leavenworth’s administration changed, and the prison was then directed by a new warden. Impressed with the possibility of presenting Leavenworth as a progressive rehabilitation penitentiary,[14] the new warden, Bennett, furnished Stroud with cages, chemicals, and stationery to conduct his ornithological activities. Visitors were shown Stroud's aviary, and many purchased his canaries. Over the years, he raised nearly 300 canaries in his cells, and wrote two books, the 60,000-word treatise Diseases of Canaries (1933), which had been smuggled out of Leavenworth,[4] and a later edition, Stroud's Digest on the Diseases of Birds (1943), with updated, specific information. He made several important contributions to avian pathology, most notably a cure for the hemorrhagic septicemia family of diseases. He gained respect and also some level of sympathy in the bird-loving field.

Stroud’s activities created problems for the prison management. According to regulations, each letter sent or received at the prison had to be read, copied, and approved. Stroud was so involved in his business that this alone required a full-time prison secretary. Additionally, most of the time, his birds were permitted to fly freely within his cells, and because of the great number of birds he kept, his cell was filthy.[15]

In 1931, an attempt to force Stroud to discontinue his business and get rid of his birds failed after Stroud and one of his mail correspondents, a bird researcher from Indiana named Della Mae Jones,[16] made his story known to newspapers and magazines. A massive letter campaign and a 50,000-signature petition sent to President Herbert Hoover resulted in Stroud being permitted to keep his birds, and despite prison overcrowding, he was even given a second cell to house them. However, his letter-writing privileges were greatly curtailed. Jones and Stroud grew so close that she moved to Kansas in 1931, and started a business with him, selling his avian medicines.[13]

Prison officials, fed up with Stroud's activities and their attendant publicity, intensified their efforts to transfer him out of Leavenworth. Stroud, however, discovered a Kansas law that forbade the transfer of prisoners married in Kansas. To this end, he married Jones by proxy, which infuriated the prison's administrators, who would not allow him to correspond with his wife.[13] Prison officials were not the only ones perturbed with Stroud's marriage; his mother was also incensed. They had a close relationship, but Elizabeth Stroud strongly disapproved of the marriage to Jones, believing women were nothing but trouble for her son. Whereas previously she had been a strong advocate for her son, helping him with legal battles, she now argued against his application for parole, and became a major obstacle in his attempts to be released from the prison system. She moved away from Leavenworth and refused any further contact with him until her death in 1937.

In 1933, Stroud advertised in a publication that he had not received any royalties from the sales of Diseases of Canaries. In retaliation, the publisher complained to the warden, and, as a result, proceedings were initiated to transfer Stroud to Alcatraz, where he would not be permitted to keep his birds. In the end, however, Stroud was able to keep both his birds and canary-selling business at Leavenworth. Stroud avoided trouble for several more years, until it came to light that some of the equipment Stroud had requested for his lab was in fact being used as a home-made still to distill alcohol.[15] Officials finally had the wedge they needed to drive Stroud out.

Alcatraz

On December 19, 1942, Stroud was transferred to Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary, and became inmate #594.[12] He reportedly was not informed in advance that he was to leave Leavenworth and his beloved birds, and was given just 10 minutes' notice of his departure; his birds and equipment were sent to his brother as Alcatraz's strict policies meant that he was unable to continue his avocation.[17] He spent six years in segregation and another 11 confined to the hospital wing there. In 1943, he was assessed by psychiatrist Romney M. Ritchey, who diagnosed him as a psychopath, but with an I.Q. of 134 (although his initial report in 1942 based on Leavenworth states that he had an I.Q. of 116). While there, he wrote two manuscripts: Bobbie, an autobiography, and Looking Outward: A History of the U.S. Prison System from Colonial Times to the Formation of the Bureau of Prisons. A judge ruled that Stroud had the right to write and keep such manuscripts, but upheld the warden’s decision to ban their publication. After Stroud's death, the transcripts were delivered to his lawyer, Richard English.

Rumors of Stroud's homosexuality were noted at Alcatraz. According to Donald Hurley, whose father was a guard at Alcatraz, "Whenever Stroud was around anyone, which was seldom, he was watched very closely, as prison officials were very aware of his overt homosexual tendencies."[18] In an interview with Hurley for his book, a former inmate heard Stroud was always in 'dog block' (solitary confinement) or later in the hospital because he was a 'wolf' (aggressive homosexual) who had a bad temper."[19] In February 1963 Stroud met and talked with actor Burt Lancaster, who portrayed him in The Birdman of Alcatraz.[20] Stroud never got to see the film or read the book it was based on but did share on one of the problems that prevented parole, that he was an "admitted homosexual."[20] Lancaster quoted Stroud as saying, "Let's face it, I am 73 years old. Does that answer your question about whether I would be a dangerous homosexual?"[20]

During his 17-year term at Alcatraz, Stroud was allowed access to the prison library, and began studying law. Occasionally, he was permitted to play chess with one of the guards.[21] Stroud began petitioning the government that his long prison term amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. In 1959, with his health failing, Stroud was transferred to the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri, where he stayed until his death in 1963.[5] However, his attempts to be released were unsuccessful.

On November 21, 1963, Robert Stroud died at the Springfield Medical Center at the age of 73, having been incarcerated for the last 54 years of his life, of which 42 were spent in solitary confinement. He had been studying French near the end of his life. Stroud is buried in Metropolis, Illinois (Massac County).[22]

Legacy

Stroud is considered to be one of the most notorious criminals in American history.[1][2][3] Robert Niemi states that Stroud had a "superior intellect," and became a "first-rate ornithologist and author," but was an "extremely dangerous and menacing psychopath, disliked and distrusted by his jailers and fellow inmates."[4] However, by his last years, he was seen more favorably, and Judge Becker considered Stroud to be modest, no longer a danger to society, with a genuine love for birds.[23] Given his level of notoriety, the crimes he committed were unremarkable,[8] especially as the assaults he committed had a clear cause. Carl Sifakais considers Stroud to have been a "brilliant self-taught expert on birds, and possibly the best-known example of self-improvement and rehabilitation in the U.S. prison."[17]

Because of Stroud's contributions to the field of ornithology, he gained a large following of thousands of bird breeders, and poultry raisers who demanded his release,[17] and for many years a "Committee to Release Robert F. Stroud" campaigned to have Stroud released from prison.[23] However, because Stroud had killed a federal officer, his punishment in solitary confinement remained intact.[17] In 1963, Richard M. English, a young lawyer who had campaigned for John F. Kennedy in California, took to the cause of securing Stroud's release. He met with former President Harry S. Truman to enlist support, but Truman declined. He also met with senior Kennedy-administration officials who were studying the subject. English took the last photo of Stroud, in which he is shown with a green visor. The warden of the prison attempted to have English prosecuted for bringing something into the prison he did not take out: unexposed film. The authorities declined to take any action. Upon Stroud's death, his personal property, including original manuscripts, was delivered to English, as his last legal representative, who later turned over some of the possessions to the Audubon Society.

Stroud became the subject of a 1955 book by Thomas E. Gaddis, Birdman of Alcatraz. Gaddis, who strongly advocated rehabilitation in the prisons, portrayed Stroud in favorable light.[4] This was adapted by Guy Trosper for the 1962 film of the same name, directed by John Frankenheimer. It starred Burt Lancaster as Stroud, Karl Malden as a fictionalized and renamed warden, and Thelma Ritter as Stroud's mother.[24] Both the book and the film were highly fictionalized, with former inmates stating that Stroud was far more sinister and unpleasant than the character depicted in them. Stroud was never allowed to see the film. Art Carney played Stroud in the 1980 TV movie Alcatraz: The Whole Shocking Story, and Dennis Farina played Stroud in the 1987 TV movie Six Against the Rock, a dramatization of the Battle of Alcatraz of 1946.[25]

In music, Stroud has been the subject of the instrumental "Birdman of Alcatraz" from Rick Wakeman's Criminal Record (1977), a concept album about criminality,[26] and the song "The Birdman" by Our Lady Peace is also about him. Several video games such as Galerians and Team Fortress 2 pay homage to him.

References

- ^ a b Gregory 2008, p. 37.

- ^ a b Ryan & Schlup 2006, p. 2012.

- ^ a b Benton 2012, p. 228.

- ^ a b c d e f Niemi 2006, p. 388.

- ^ a b c d e "Robert Stroud". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Odier 1982, p. 210.

- ^ a b c d Campbell 1994, p. 66.

- ^ a b Mayo 2008, p. 342.

- ^ "Officer Andrew Turner". ODMP. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Campbell 1994, p. 67.

- ^ "Robert Stroud". Time. 4 January 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Wellman 2008, p. 57.

- ^ a b c United States. Congress (1962). Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 14647–49.

- ^ LIFE. Time Inc. 2 May 1960. p. 16. ISSN 0024-3019. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ a b Sloate 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Crowther 1989, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d Sifakis 2002, p. 246.

- ^ Hurley 1994, p. 69.

- ^ Hurley 1994, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Miller, Johnny (17 November 2013). "Chronicle Archives Wayback Machine: Canseco earns MVP honor, Nov. 17, 1988, 1963". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Sloate 2008, p. 34.

- ^ "Robert Stroud". Find A Grave. 1 January 2001. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ a b National Archives (1991). Prologue: the journal of the National Archives. National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration. pp. 155–9. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ MacDonald 2012, p. 243.

- ^ Rabkin 1998, p. 187.

- ^ "Rick Wakeman's Criminal Record". Prog Archives. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- Bibliography

- Benton, Lisa M. (1998). The Presidio: From Army Post to National Park. UPNE. ISBN 978-1-55553-335-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, Douglas S. (1994). Free Press V. Fair Trial: Supreme Court Decisions Since 1807. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-275-94277-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crowther, Bruce (1989). Captured On Film: The Prison Movie. Batsford.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gregory, George H. (28 April 2008). Alcatraz Screw: My Years as a Guard in America's Most Notorious Prison. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1396-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hurley, Donald J. (1994). Alcatraz Island: Maximum Security. Fog Bell Enterprises. ISBN 978-0-9620546-2-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacDonald, Donald; Nadel, Ira (3 February 2012). Alcatraz: History and Design of a Landmark. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-1310-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mayo, Mike (2008). American Murder: Criminals, Crimes, and the Media. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1-57859-191-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Niemi, Robert (2006). History in the Media: Film and Television. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-952-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Odier, Pierre (1982). The Rock: A History of Alcatraz: The Fort/The Prison. L'Image Odier. ISBN 978-0-9611632-0-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rabkin, Leslie Y. (1 September 1998). The Celluloid Couch: An annotated international filmography of the mental health professional in the movies and television, from the beginning to 1990. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3462-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ryan, James Gilbert; Schlup, Leonard C. (30 June 2006). Historical Dictionary of The 1940s. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0440-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sifakis, Carl (2002). The Encyclopedia of American Prisons. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-2987-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sloate, Susan (2008). The Secrets of Alcatraz. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4027-3591-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wellman, Gregory L. (2008). A History of Alcatraz Island: 1853-2008. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5815-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- 1890 births

- 1963 deaths

- American people of German descent

- Inmates of Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary

- American memoirists

- American ornithologists

- American ornithological writers

- American male writers

- American people convicted of manslaughter

- American people who died in prison custody

- American prisoners sentenced to death

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- American people convicted of assault

- People from Seattle

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by the United States federal government

- Prisoners who died in United States federal government detention

- 20th-century American criminals