SMS Helgoland (1909)

SMS Helgoland c. 1911–1917

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Helgoland |

| Builder | Howaldtswerke, Kiel |

| Laid down | 11 November 1908 |

| Launched | 25 September 1909 |

| Commissioned | 23 August 1911 |

| Fate | Scrapped in 1921 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Template:Sclass- |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 167.20 m (548 ft 7 in) |

| Beam | 28.50 m (93 ft 6 in) |

| Draft | 8.94 m (29 ft 4 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 20.8 knots (38.5 km/h; 23.9 mph) |

| Range | 5,500 nautical miles (10,190 km; 6,330 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

SMS Helgoland,[a] the lead ship of her class, was a dreadnought battleship of the German Imperial Navy. Helgoland's design represented an incremental improvement over the preceding Template:Sclass-, including an increase in the bore diameter of the main guns, from 28 cm (11 in) to 30.5 cm (12 in). Her keel was laid down on 11 November 1908 at the Howaldtswerke shipyards in Kiel. Helgoland was launched on 25 September 1909 and was commissioned on 23 August 1911.

Like most battleships of the High Seas Fleet, Helgoland saw limited action against Britain's Royal Navy during World War I. The ship participated in several fruitless sweeps into the North Sea as the covering force for the battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group. She saw some limited duty in the Baltic Sea against the Russian Navy, including serving as part of a support force during the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in August 1915. Helgoland was present at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916, though she was located in the center of the German line of battle and not as heavily engaged as the Template:Sclass-- and Template:Sclass- ships in the lead. Helgoland was ceded to Great Britain at the end of the war and broken up for scrap in the early 1920s. Her coat of arms is preserved in the Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr in Dresden.

Design

The ship was 167.2 m (548 ft 7 in) long, had a beam of 28.5 m (93 ft 6 in) and a draft of 8.94 m (29 ft 4 in), and displaced 24,700 metric tons (24,310 long tons) at full load. She was powered by three vertical triple expansion steam engines, which produced a top speed of 20.8 knots (38.5 km/h; 23.9 mph). Helgoland stored up to 3,200 metric tons (3,100 long tons) of coal, which allowed her to steam for 5,500 nautical miles (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). After 1915 the boilers were modified to burn oil; the ship could carry up to 197 metric tons (194 long tons) of fuel oil.[1] She had a crew of 42 officers and 1,071 enlisted men.[2]

Helgoland was armed with a main battery of twelve 30.5 cm (12 in) SK L/50[b] guns in six twin gun turrets, with one turret fore, one aft, and two on each flank of the ship.[4] The ship's secondary armament consisted of fourteen 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns and sixteen 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 guns.[1] After 1914, two of the 8.8 cm guns were removed and replaced by 8.8 cm anti-aircraft guns. Helgoland was also armed with six 50 cm (20 in) submerged torpedo tubes.[2]

Her main armored belt was 300 mm (12 in) thick in the central portion, and was composed of Krupp cemented armor (KCA). Her main battery gun turrets were protected by the same thickness of KCA on the sides and faces, as well as the barbettes that supported the turrets. Helgoland's deck was 63.5 mm (2.5 in) thick.[1]

Service history

Helgoland was ordered by the German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) under the provisional name Ersatz Siegfried, as a replacement for the old coastal defense ship Siegfried. The contract for the ship was awarded to Howaldtswerke in Kiel under construction number 500.[1] Work began on 24 December 1908 with the laying of her keel, and the ship was launched less than a year later, on 25 September 1909.[5] Fitting-out, including completion of the superstructure and the installation of armament, lasted until August 1911. Helgoland, named for the offshore islands seen as vital to the defense of the Kiel Canal,[6] was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 23 August 1911, just under three years from when work commenced.[2]

Upon commissioning, Helgoland replaced the pre-dreadnought Hannover in I Battle Squadron.[7] On 9 February 1912, Helgoland's crew beat the German record for loading coal, taking 1,100 tons of coal on board in two hours; the record was previously held by the crew of the Nassau-class battleship Posen. Kaiser Wilhelm II congratulated the crew through a Cabinet order.[8] In March, fleet training maneuvers were conducted in the North Sea, followed by another round of exercises in November. The fleet also trained in the Skagerrak and Kattegat during the November exercises. The next year followed a similar training pattern, though a summer cruise to Norway was instituted.[7]

On 10 July 1914, Helgoland left the Jade Estuary to take part in the annual summer training cruise to Norway. The fleet, along with several German U-boats, assembled at Skagen on 12 July to practice torpedo boat attacks, individual ship maneuvers, and searchlight techniques. The fleet arrived at the Fjord of Songe by 18 July, but Helgoland had to wait until after midnight for a harbor pilot to guide her into the confined waters of the fjord.[9] Helgoland joined Friedrich der Grosse, the light cruiser Magdeburg, and the Kaiser's yacht Hohenzollern in Balholm.[10] That same day, Helgoland took on 1250 tons of coal from a Norwegian collier.[11] The following morning Helgoland was joined by her sister Oldenburg, and the two ships sailed back to Germany, arriving on the morning of 22 July.[12] On the evening of 1 August, the captain announced to the crew that the Kaiser had ordered the navy to prepare for hostilities with the Russian Navy.[13]

World War I

At the start of World War I, Helgoland was assigned to I Division, I Battle Squadron.[14] Helgoland was stationed off the heavily fortified island of Wangerooge on 9 August. Minefields and picket lines of cruisers, torpedo boats, and submarines were also emplaced there to defend Wilhelmshaven. Helgoland's engines were kept running for the entirety of her deployment, so that she would be ready to respond at a moment's notice.[15] Four days later, on 13 August, Helgoland returned to Wilhelmshaven to refuel.[16] The following day, naval reservists began arriving to fill out the wartime complements for the German battleships.[17]

The first major naval action in the North Sea, the Battle of Helgoland Bight, took place on 28 August 1914. Helgoland was again stationed off Wangerooge. Despite her proximity to the battle, Helgoland was not sent to aid the beleaguered German cruisers, as she could not be risked in an unsupported attack against possibly superior British forces.[18] Instead, the ship was ordered to drop anchor and await relief by Thüringen.[19] By 04:30, Helgoland received the order to join Ostfriesland and sail out of the harbor. At 05:00, the two battleships met the battered cruisers Frauenlob and Stettin.[20] By 07:30, the ships had returned to port for the night.[21] Three days later, on 31 August, Helgoland was put into drydock for maintenance.[22] On the afternoon of 7 September, Helgoland and the rest of the High Seas Fleet conducted a training cruise to the main island of Helgoland.[23]

Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

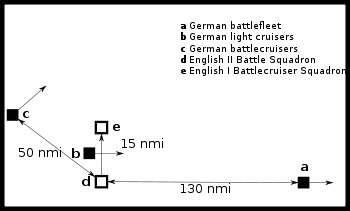

The first major operation of the war in which Helgoland took part was the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on 15–16 December 1914. The raid was conducted by the battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group; Helgoland and the other dreadnoughts of the High Seas Fleet steamed in distant support of Franz von Hipper's battlecruisers. Friedrich von Ingenohl, the commander of the High Seas Fleet, decided to take up station in the middle of the North Sea, about 130 miles east of Scarborough.[24]

The Royal Navy, which had recently received the German code books captured from the beached cruiser Magdeburg, was aware that an operation was taking place, but was not sure where the Germans would strike. Therefore, the Admiralty ordered David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron, the six battleships of the 2nd Battle Squadron, and several cruisers and destroyers to intercept the German battlecruisers.[24] However, Beatty's task force nearly ran headlong into the entire High Seas Fleet. At 06:20, Beatty's destroyer screen came into contact with the German torpedo boat SMS V155. This began a confused, 2-hour battle between the British destroyers and the German cruiser and destroyer screen, often at very close range. At the time of the first encounter, the Helgoland-class battleships were less than 10 nautical miles (19 km; 12 mi) away from the six British dreadnoughts; this was nearly within firing range, but in the darkness, neither British nor German admirals were aware of the composition of their opponents' fleets. Admiral Ingenohl, aware of the Kaiser's order not to risk the battle fleet without his express approval, concluded that his forces were engaging the screen of the entire Grand Fleet, and so, 10 minutes after the first contact, he ordered a turn to the southeast. Continued attacks delayed the turn, but by 06:42, it had been carried out.[25] For about 40 minutes, the two fleets were steaming on a parallel course. At 07:20, Ingenohl ordered a further turn to port, which put his ships on a course for the safety of German bases.[26]

On 17 January, Ingenohl ordered Helgoland to go back to the docks for more maintenance, but she did not enter the drydock until three days later, owing to difficulties getting through the canal locks.[27] By the middle of the month, Helgoland left dock; her berth was then filled by the armored cruiser SMS Roon.[28] On 10 February, Helgoland and the rest of I Squadron sailed out of Wilhelmshaven towards Cuxhaven, but heavy fog impeded movement for two days. The ships then anchored off Brunsbüttel before proceeding through the Kiel Canal to Kiel.[29] The crews conducted gunnery training with the main and secondary guns and torpedo firing practice on 1 March.[30] The following night the crews conducted night-fighting training. On 10 March the squadron again passed through the locks to return to Wilhelmshaven.[31] Fog again slowed progress, and the ships did not reach port until 15 March.[32]

Battle of the Gulf of Riga

Helgoland, her three sister ships, and the four Nassau-class battleships were assigned to the task force that was to cover the foray into the Gulf of Riga in August 1915. The German flotilla, which was under the command of Hipper, also included the battlecruisers Von der Tann, Moltke, and Seydlitz, several light cruisers, 32 destroyers and 13 minesweepers. The plan called for channels in Russian minefields to be swept so that the Russian naval presence, which included the pre-dreadnought battleship Slava, could be eliminated. The Germans would then lay minefields of their own to prevent Russian ships from returning to the gulf.[33] Helgoland and the majority of the other big ships of the High Seas Fleet remained outside the gulf for the entirety of the operation. The dreadnoughts Nassau and Posen were detached on 16 August to escort the minesweepers and to destroy Slava, though they failed to sink the old battleship. After three days, the Russian minefields had been cleared, and the flotilla entered the gulf on 19 August, but reports of Allied submarines in the area prompted a German withdrawal from the gulf the following day.[34]

Battle of Jutland

Under the command of Captain von Kameke,[35] Helgoland fought at the Battle of Jutland, alongside her sister ships in I Battle Squadron. For the majority of the battle, I Battle Squadron formed the center of the line of battle, behind Rear Admiral Behncke's III Battle Squadron, and followed by Rear Admiral Mauve's elderly pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron.[14]

Helgoland and her sisters first entered direct combat shortly after 18:00. The German line was steaming northward and encountered the destroyers Nomad and Nestor, which had been disabled earlier in the battle. Nomad, which had been attacked by the Template:Sclass- ships at the head of the line, exploded and sank at 18:30, followed five minutes later by the Nestor, sunk by main and secondary gunfire from Helgoland, Thüringen and several other German battleships.[36] At 19:20, Helgoland and several other battleships began firing on HMS Warspite, which, along with the other Template:Sclass-s of the 5th Battle Squadron, had been pursuing the German battlecruiser force. The shooting stopped quickly though, as the Germans lost sight of their target; Helgoland had fired only about 20 shells from her main guns.[37]

At 20:15, during the third Gefechtskehrtwendung,[c] Helgoland was struck by a 15-inch (38 cm) armor-piercing (AP) shell, from either Barham or Valiant, in the forward part of the ship. The shell hit the armored belt about 0.8 m (32 in) above the waterline, where the armor was only 15 cm thick. The 15-inch shell broke up on impact, but it still managed to tear a 1.4-meter (4 ft 7 in) hole in the hull.[39] It rained splinters on the foremost port side 15 cm gun, though it could still be fired.[40] Approximately 80 tons of water entered the ship.[41]

By 23:30, the High Seas Fleet had entered its night cruising formation. The order had largely been inverted, with the four Nassau-class ships in the lead, followed directly by the Helgolands, with the Kaisers and Königs astern of them. The rear was again brought up by the elderly pre-dreadnoughts; the mauled German battlecruisers were by this time scattered.[42] At around midnight on 1 June, the Helgoland- and Nassau-class ships in the center of the German line came into contact with the British 4th Destroyer Flotilla. The 4th Flotilla broke off the action temporarily to regroup, but at around 01:00, unwittingly stumbled into the German dreadnoughts a second time.[43] Helgoland and Oldenburg opened fire on the two leading British destroyers.[44] Helgoland fired six salvos from her secondary guns at the destroyer Fortune before she succumbed to the tremendous battering.[45] Shortly after, Helgoland shifted fire to an unidentified destroyer; Helgoland fired five salvos from her 15 cm guns to unknown effect.[46] The British destroyers launched torpedoes at the German ships, but they managed to successfully evade them with a turn to starboard.[47]

Following the return to German waters, Helgoland and Thüringen, along with the Template:Sclass-s Nassau, Posen, and Westfalen, took up defensive positions in the Jade roadstead for the night. During the battle, the ship suffered only minor damage; Helgoland was hit by a single 15-inch shell, but sustained minimal damage.[48] Nevertheless, dry-docking was required to repair the hole in the belt armor. Work was completed by 16 June.[49] In the course of the battle, Helgoland had fired 63 main battery shells,[50] and 61 rounds from her 15 cm guns.[51]

Later career

After the Battle of Jutland, Admiral Scheer argued that the fleet could not break the British naval blockade, that only the resumption of unrestricted U-boat warfare would be successful. As a result, the High Seas Fleet largely remained in port, with the exception of two abortive sorties in August and October 1916.[52] In April 1917, Helgoland accidentally rammed the new battlecruiser Hindenburg, which was in the process of fitting-out, as she left her berth.[7] In October 1917 Helgoland, in company with Oldenburg, went to Amrum to receive the light cruisers Brummer and Bremse, which were returning from a raid on a British convoy to Norway. On 27 November the ship traversed the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal into the Baltic, but did not participate in the occupation of the islands in the Gulf of Riga.[7] A third and final fleet advance took place in April 1918, but was cut short when the battlecruiser Moltke developed engine problems and had to be towed back to port.[53]

Helgoland and her three sisters were to have taken part in a final fleet action days before the Armistice was to take effect. The bulk of the High Seas Fleet was to have sortied from their base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet; Scheer—by now the Grand Admiral (Großadmiral) of the fleet—intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to retain a better bargaining position for Germany, despite the expected casualties. However, many of the war-weary sailors felt the operation would disrupt the peace process and prolong the war.[54] On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen and then on several other battleships mutinied.[55]

Early on the 30th, the crew of Helgoland, which was directly behind Thüringen in the harbor, joined in the mutiny. The I Squadron commander sent boats to Helgoland and Thüringen to take off the ships' officers, who were allowed to leave unharmed. He then informed the rebellious crews that if they failed to stand down, both ships would be torpedoed. After two torpedo boats arrived on the scene, both ships surrendered; their crews were taken ashore and incarcerated.[56] The rebellion then spread ashore; on 3 November, an estimated 20,000 sailors, dock workers, and civilians fought a battle in Kiel in an attempt to secure the release of the jailed mutineers.[57] By 5 November, the red flag of the Socialists flew above every capital ship in Wilhelmshaven save König. The following day, a sailors' council took control of the base, and a train carrying the mutineers from Helgoland and Thüringen was stopped in Cuxhaven, where the men escaped.[57]

According to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, all four Helgoland-class battleships were disarmed and surrendered as prizes of war to the Allies as replacements for the ships scuttled in Scapa Flow.[58][59] On 21–22 November 1918, Helgoland steamed to Harwich to retrieve the crews of U-boats that had been surrendered there. She was then removed from active service on 16 December 1918.[7] Helgoland and her sisters were stricken from the German navy on 5 November 1919.[60] Helgoland was formally handed over to the United Kingdom on 5 August 1920. She was scrapped at Morecambe; work began on 3 March 1921. Helgoland's coat of arms is currently preserved in the Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr in Dresden.[2]

Footnotes

Notes

- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (Template:Lang-de).

- ^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/50 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/50 gun is 50 caliber, meaning that the gun is 50 times as long as its diameter.[3]

- ^ This translates roughly as the "battle about-turn", and was a simultaneous 16-point turn of the entire High Seas Fleet. It had never been conducted under enemy fire before the Battle of Jutland.[38]

Citations

- ^ a b c d Gröner, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Gröner, p. 25.

- ^ Grießmer, p. 177.

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 146.

- ^ Sturton, p. 31.

- ^ Herwig, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e Staff (Battleships), p. 42.

- ^ Stumpf, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Stumpf, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Stumpf, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 22.

- ^ Stumpf, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Tarrant, p. 286.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 29.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 30.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 32.

- ^ Osborne, p. 41.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 38.

- ^ Stumpf, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 42.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 44.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 46.

- ^ a b Tarrant, p. 31.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 32.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 33.

- ^ Stumpf, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 63.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 67.

- ^ Stumpf, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 72.

- ^ Stumpf, p. 74.

- ^ Halpern, p. 196.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Scheer, p. 137.

- ^ Campbell, p. 101.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Campbell, p. 245.

- ^ Campbell, p. 246.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 173, 175.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 222.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 223.

- ^ Campbell, p. 289.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 224.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 263.

- ^ Campbell, p. 336.

- ^ Campbell, p. 348.

- ^ Campbell, p. 359.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 330–332.

- ^ Staff (Battlecruisers), p. 17.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 281–282.

- ^ New York Times Co., p. 440.

- ^ a b Schwartz, p. 48.

- ^ Treaty of Versailles, Article 185.

- ^ Hore, p. 68.

- ^ Miller, p. 101.

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hore, Peter (2006). Battleships of World War I. London: Southwater Books. ISBN 978-1-84476-377-1.

- Miller, David (2001). Illustrated Directory of Warships of the World. Osceola, Wisconsin: Zenith Imprint. ISBN 978-0-7603-1127-1.

- New York Times Co. (1919). The New York Times Current History: Jan.–March, 1919. New York: The New York Times Company.

- Naval Institute Proceedings. Vol. 38. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. 1912.

- Osborne, Eric W. (2006). The Battle of Heligoland Bight. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34742-8.

- Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 2765294.

- Schwartz, Stephen (1986). Brotherhood of the Sea: A History of the Sailors' Union of the Pacific, 1885–1985. San Francisco: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88738-121-8.

- Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-009-3.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. Vol. 1: Deutschland, Nassau and Helgoland Classes. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

- Stumpf, Richard (1967). Horn, Daniel (ed.). War, Mutiny and Revolution in the German Navy: The World War I Diary of Seaman Richard Stumpf. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Sturton, Ian, ed. (1987). Conway's All the World's Battleships: 1906 to the Present. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-448-0.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.