SN1 reaction

The SN1 reaction is a substitution reaction in organic chemistry. "SN" stands for nucleophilic substitution and the "1" represents the fact that the rate-determining step is unimolecular.[1][2] Thus, the rate equation is often shown as having first-order dependence on electrophile and zero-order dependence on nucleophile. This relationship holds for situations where the amount of nucleophile is much greater than that of the carbocation intermediate. Instead, the rate equation may be more accurately described using steady-state kinetics. The reaction involves a carbocation intermediate and is commonly seen in reactions of secondary or tertiary alkyl halides under strongly basic conditions or, under strongly acidic conditions, with secondary or tertiary alcohols. With primary alkyl halides, the alternative SN2 reaction occurs. In inorganic chemistry, the SN1 reaction is often known as the dissociative mechanism. This dissociation pathway is well-described by the cis effect. A reaction mechanism was first proposed by Christopher Ingold et al. in 1940.[3] This reaction does not depend much on the strength of the nucleophile unlike the SN2 mechanism.

Mechanism

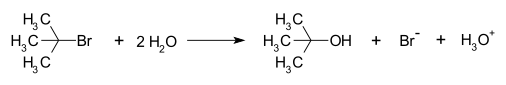

An example of a reaction taking place with an SN1 reaction mechanism is the hydrolysis of tert-butyl bromide with water forming tert-butanol:

This SN1 reaction takes place in three steps:

- Formation of a tert-butyl carbocation by separation of a leaving group (a bromide anion) from the carbon atom: this step is slow and reversible.[4]

- Nucleophilic attack: the carbocation reacts with the nucleophile. If the nucleophile is a neutral molecule (i.e. a solvent) a third step is required to complete the reaction. When the solvent is water, the intermediate is an oxonium ion. This reaction step is fast.

- Deprotonation: Removal of a proton on the protonated nucleophile by water acting as a base forming the alcohol and a hydronium ion. This reaction step is fast.

Scope

The SN1 mechanism tends to dominate when the central carbon atom is surrounded by bulky groups because such groups sterically hinder the SN2 reaction. Additionally, bulky substituents on the central carbon increase the rate of carbocation formation because of the relief of steric strain that occurs. The resultant carbocation is also stabilized by both inductive stabilization and hyperconjugation from attached alkyl groups. The Hammond-Leffler postulate suggests that this too will increase the rate of carbocation formation. The SN1 mechanism therefore dominates in reactions at tertiary alkyl centers and is further observed at secondary alkyl centers in the presence of weak nucleophiles.

An example of a reaction proceeding in a SN1 fashion is the synthesis of 2,5-dichloro-2,5-dimethylhexane from the corresponding diol with concentrated hydrochloric acid:[5]

As the alpha and beta substitutions increase with respect to leaving groups the reaction is diverted from SN2 to SN1.

Stereochemistry

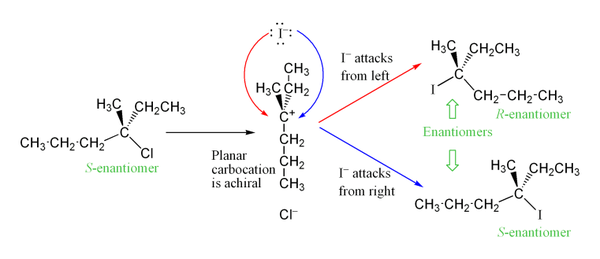

The carbocation intermediate formed in the reaction's rate limiting step is an sp2 hybridized carbon with trigonal planar molecular geometry. This allows two different avenues for the nucleophilic attack, one on either side of the planar molecule. If neither avenue is preferentially favored, these two avenues occur equally, yielding a racemic mix of enantiomers if the reaction takes place at a stereocenter.[6] This is illustrated below in the SN1 reaction of S-3-chloro-3-methylhexane with an iodide ion, which yields a racemic mixture of 3-iodo-3-methylhexane:

However, an excess of one stereoisomer can be observed, as the leaving group can remain in proximity to the carbocation intermediate for a short time and block nucleophilic attack. This stands in contrast to the SN2 mechanism, which is a stereospecific mechanism where stereochemistry is always inverted as the nucleophile comes in from the rear side of the leaving group.

Side reactions

Two common side reactions are elimination reactions and carbocation rearrangement. If the reaction is performed under warm or hot conditions (which favor an increase in entropy), E1 elimination is likely to predominate, leading to formation of an alkene. At lower temperatures, SN1 and E1 reactions are competitive reactions and it becomes difficult to favor one over the other. Even if the reaction is performed cold, some alkene may be formed. If an attempt is made to perform an SN1 reaction using a strongly basic nucleophile such as hydroxide or methoxide ion, the alkene will again be formed, this time via an E2 elimination. This will be especially true if the reaction is heated. Finally, if the carbocation intermediate can rearrange to a more stable carbocation, it will give a product derived from the more stable carbocation rather than the simple substitution product.

Solvent effects

Since the SN1 reaction involves formation of an unstable carbocation intermediate in the rate-determining step, anything that can facilitate this will speed up the reaction. The normal solvents of choice are both polar (to stabilize ionic intermediates in general) and protic (to solvate the leaving group in particular). Typical polar protic solvents include water and alcohols, which will also act as nucleophiles and the process is known as solvolysis.

The Y scale correlates solvolysis reaction rates of any solvent (k) with that of a standard solvent (80% v/v ethanol/water) (k0) through

with m a reactant constant (m = 1 for tert-butyl chloride) and Y a solvent parameter.[7] For example 100% ethanol gives Y = −2.3, 50% ethanol in water Y = +1.65 and 15% concentration Y = +3.2.[8]

See also

References

- ^ L. G. Wade, Jr., Organic Chemistry, 6th ed., Pearson/Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA, 2005

- ^ March, J. (1992). Advanced Organic Chemistry (4th ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-60180-2.

- ^ Leslie C. Bateman, Mervyn G. Church, Edward D. Hughes, Christopher K. Ingold and Nazeer Ahmed Taher (1940). "188. Mechanism of substitution at a saturated carbon atom. Part XXIII. A kinetic demonstration of the unimolecular solvolysis of alkyl halides. (Section E) a general discussion". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 979. doi:10.1039/JR9400000979.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peters, K. S. (2007). "Nature of Dynamic Processes Associated with the SN1 Reaction Mechanism". Chem. Rev. 107 (3): 859–873. doi:10.1021/cr068021k. PMID 17319730.

- ^ Synthesis of 2,5-Dichloro-2,5-dimethylhexane by an SN1 Reaction Carl E. Wagner and Pamela A. Marshall , J. Chem. Educ., 2010, 87 (1), pp 81–83 doi:10.1021/ed8000057

- ^ Sorrell, Thomas N. "Organic Chemistry, 2nd Edition" University Science Books, 2006

- ^ Ernest Grunwald and S. Winstein (1948). "The Correlation of Solvolysis Rates". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 70 (2): 846. doi:10.1021/ja01182a117.

- ^ Arnold H. Fainberg and S. Winstein (1956). "Correlation of Solvolysis Rates. III.1 t-Butyl Chloride in a Wide Range of Solvent Mixtures". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 78 (12): 2770. doi:10.1021/ja01593a033.

Further reading

- Electrophilic Bimolecular Substitution as an Alternative to Nucleophilic Monomolecular Substitution in Inorganic and Organic Chemistry / N.S.Imyanitov. J. Gen. Chem. USSR (Engl. Transl.) 1990; 60 (3); 417-419.

- Unimolecular Nucleophilic Substitution does not Exist! / N.S.Imyanitov. SciTecLibrary

External links

- Diagrams: Frostburg State University

- Exercise: the University of Maine