Santorio Santorio

Santorio Santorio | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 29, 1561 |

| Died | February 22, 1636 (aged 74) |

Santorio Santorio (29 March 1561 – 22 February 1636 Venice),[1] also called Sanctorio Sanctorio, Santorio Santorii, Sanctorius of Padua, and various combinations of these names, was a Venetian physiologist, physician, and professor, who introduced the quantitative approach into medicine. He is also known as the inventor of several medical devices, including the thermometer. His work De Statica Medicina, written in 1614, saw five publications through 1737[citation needed] and influenced generations of physicians.[2]

Life

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2015) |

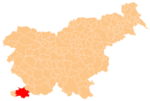

Santorio was born in the Mediterranean coastal town of Capodistria (today Koper, southwestern Slovenia, then part of the Republic of Venice). From 1611 to 1624 he was a professor at Padua where he performed experiments in temperature, respiration and weight.

Work

Inventions

Santorio was the first to use a wind gauge, a water current meter, the pulsilogium (a device used to measure the pulse rate), an early waterbed[citation needed], and a thermoscope. Whereas he invented the former two devices, it is unclear exactly who invented the latter two; it could be his friend Galileo Galilei or another person of the learned circle in Venice of which they were members.[3]

He also invented a device which he called the "trocar" (not identical to the modern trocar) for removing bladder stones.[4]

Santorio introduced the thermoscope in the work titled Sanctorii Sanctorii Commentaria in Artem medicinalem Galeni in 1612.[5]

The pulsilogium was probably the first machine of precision in medical history.[citation needed] A century later another physician, de Lacroix, used the pulsilogium to test cardiac function.[citation needed]

Study of metabolism

Sanctorius studied the so-called perspiratio insensibilis or insensible perspiration of the body, already known to Galen and ancient physicians, and originated the study of metabolism. For a period of thirty years Santorio weighed himself, everything he ate and drank, as well as his urine and feces. He compared the weight of what he had eaten to that of his waste products, the latter being considerably smaller because for every eight pounds of food he ate, he excreted only 3 pounds of waste. This important experiment is the origin of the significance of weight measurement in medicine.[6] While his experiments kept to be replicated and augmented by his followers and were finally surpassed by the ones of Lavoisier in 1790, he is still celebrated as the father of experimental physiology. The "weighing chair", which he constructed and employed during this experiment, is also famous.

References

- ^ Pintar, Ivan (1925–1991 (printed ed.). 2009 (electronic ed.)). "Sanctorius Sanctorius". In Vide Ogrin, Petra (electronic ed.). Cankar, Izidor et al. (printed ed.) (ed.). Slovenski biografski leksikon (in Slovenian). ISBN 978-961-268-001-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Zupanič Slavec, Zvonka (2001). "Vpliv Santorijevih del na Dubrovčana Đura Armena Baglivija" (PDF). Medicinski razgledi (in Slovenian and English). 40 (4): 443–450.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Van Helden, Albert. "Galileo Project" (PDF). Rice University. pp. 28–29. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Daniel Boorsten, The Discoverers, Chap. 49

- ^ Kelly, Kate (2010). "Santorio and the Body as a Machine". The Scientific Revolution and Medicine: 1450-1700. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438126364.

- ^ Kuriyama, Shigehisa. "The Forgotten Fear of Excrement." Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. (2008): n. page. Print.

External links

- A project on Santorio Santorio and the Emergence of Quantifying Procedures in Medicine is currently hosted by the Centre for Medical History of the University of Exeter (UK)

- An introductory video on Santorio's life and works here