Secondary growth

In botany, secondary growth is the growth that results from cell division in the cambia or lateral meristems and that causes the stems and roots to thicken, while primary growth is growth that occurs as a result of cell division at the tips of stems and roots, causing them to elongate, and gives rise to primary tissue. Secondary growth occurs in most seed plants, but monocots usually lack secondary growth. If they do have secondary growth, it differs from the typical pattern of other seed plants.

The formation of secondary vascular tissues from the cambium is a characteristic feature of dicotyledons and gymnosperms. In certain monocots, the vascular tissues are also increased after the primary growth is completed but the cambium of these plants is of a different nature. In the living pteridophytes this feature is extremely rare, only occurring in Isoetes.

Lateral meristems

[edit]

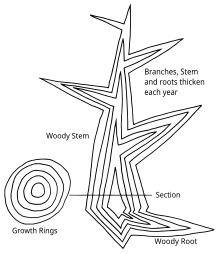

In many vascular plants, secondary growth is the result of the activity of the two lateral meristems, the cork cambium and vascular cambium. Arising from lateral meristems, secondary growth increases the width of the plant root or stem, rather than its length. As long as the lateral meristems continue to produce new cells, the stem or root will continue to grow in diameter. In woody plants, this process produces wood, and shapes the plant into a tree with a thickened trunk.

Because this growth usually ruptures the epidermis of the stem or roots, plants with secondary growth usually also develop a cork cambium. The cork cambium gives rise to thickened cork cells to protect the surface of the plant and reduce water loss. If this is kept up over many years, this process may produce a layer of cork. In the case of the cork oak it will yield harvestable cork.

In nonwoody plants

[edit]Secondary growth also occurs in many nonwoody plants, e.g. tomato,[1] potato tuber, carrot taproot and sweet potato tuberous root. A few long-lived leaves also have secondary growth.[2]

Abnormal secondary growth

[edit]

Abnormal secondary growth does not follow the pattern of a single vascular cambium producing xylem to the inside and phloem to the outside as in ancestral lignophytes. Some dicots have anomalous secondary growth, e.g. in Bougainvillea a series of cambia arise outside the oldest phloem.[4]

Ancestral monocots lost their secondary growth and their stele has changed in a way it could not be recovered without major changes that are very unlikely to occur. Monocots either have no secondary growth, as is the ancestral case, or they have an "anomalous secondary growth" of some type, or, in the case of palms, they enlarge their diameter in what is called a sort of secondary growth or not depending on the definition given to the term. Palm trees increase their trunk diameter due to division and enlargement of parenchyma cells, which is termed "primary gigantism"[3] because there is no production of secondary xylem and phloem tissues,[3][5] or sometimes "diffuse secondary growth".[6] In some other monocot stems as in Yucca and Dracaena with anomalous secondary growth, a cambium forms, but it produces vascular bundles and parenchyma internally and just parenchyma externally. Some monocot stems increase in diameter due to the activity of a primary thickening meristem, which is derived from the apical meristem.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Thompson, N.P. and Heimsch, C. 1964. Stem anatomy and aspects of development in tomato. American Journal of Botany 51: 7-19. [1]

- ^ Ewers, F.W. 1982. Secondary growth in needle leaves of Pinus longaeva (bristlecone pine) and other conifers: Quantitative data. American Journal of Botany 69: 1552-1559. [2]

- ^ a b c James D. Mauseth, 2003. Botany: An Introduction to Plant Biology, Third Edition.

- ^ Esau, K. and Cheadle, V.I. 1969. Secondary growth in bougainvillea. Annals of Botany 33: 807-819. [3]

- ^ MG Simpson (2005) "Arecaceae (Palmae)" In: Plant Systematics. p.185: "...Plant sex is variable, and secondary growth is absent..."

- ^ Esau, K. 1977. Anatomy of Seed Plants. New York: Wiley

- ^ Augusto, S. C.; Garófalo, C. A. (2004-11-01). "Nesting biology and social structure of Euglossa (Euglossa) townsendi Cockerell (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Euglossini)". Insectes Sociaux. 51 (4): 400–409. doi:10.1007/s00040-004-0760-2. ISSN 0020-1812. S2CID 13448653.